In Memory of Iohan

In Memory of Iohan

“I Iohan want to see the world. Follow a map to its edges, and keep going. Forgo the plans, trust my instincts. Let curiosity be my guide. I want to change hemispheres. Sleep with unfamiliar stars. And let the journey unfold before me.”

Iohan Gueorguiev was an adventurer. He captivated the minds of countless people as he traveled by bicycle and packraft across the Americas, documenting his amazing adventures on his YouTube channel in a video series titled See The World. Beginning in the ice roads of northern Canada in 2014, he spent months traversing the Yukon and Alaskan highways before making his way through the American national parks and continuing south through Mexico. After volcano hopping in the Central American jungles and taking a paddling detour around the Darien Gap, he finally reached the shores of Colombia, all while filming and uploading his footage for us to enjoy. Years and countless stories later, he reached the high mountains of Patagonia at Lake O’Higgins before returning to Canada to work and wait through the pandemic.

And that was where his epic Pan-American adventure came to an abrupt and tragic end. The cycling community received a note from one of his touring friends in Argentina that he passed away about a month ago. That he suffered from chronic sleep apnea and insomnia, to the degree that he took his own life to end the pain. So many of us had come to love his videos over the years, and were shocked and saddened that this would happen to such a brilliant soul. I’m still trying to process my own feelings as I write these words.

I followed Iohan for years. He was one of the first people to truly inspire me to go on my own adventures and capture the experiences in video and written word. He had a purity to him that I always admired. His sense of adventure was simple, and genuine. Whether making friends with stray dogs, staying with host families in remote villages, or shooting an epic panorama, he was always able to capture the moment and tell a story that connects and resonates with us.

And so as I go through his old videos, so many things come back to memory. Like the Athabascan woman who sang about Denali in her native tongue. Or when he crossed paths with Sarah Outen on the Alcan Highway. And then camped on a volcano high above Guadalajara. And the time he tried to ride the back roads in Panama, only to see them turn into a mudslide and force him to hitch a ride out in somebody’s truck. And of course there were the incredible panoramas of the remote Bolivian highlands. To the soundtrack of Spanish folk music, Iohan was riding on the bottom of the screen, trying to fit the huge landscapes of the Andes into the picture.

And he was always meeting kind folks and animals along the road. He was a friend among many horses, dogs, cats, alpacas, and townsfolk. And yet, always moving on. Because he wanted to see the world. He wanted to follow the map to its edges and keep going. He wanted to let the journey unfold before him. And then he wanted to share it with us.

It’s impossible to say how many of us have been impacted and inspired by his journey – one so suddenly brought to an end. It never seems fair to see life taken away from someone who lived it to its fullest. But this is a story that will live on. As I speak, a group of his friends are planning a memorial in Ushuaia. I want to see it one day and thank him for sharing his life adventure.

He is Iohan, the Bike Wanderer. And while he may no longer be with us, our hearts are with him in the wilds of Patagonia.

The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl

The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl

Over the last few years, the sport of packrafting has grown from a small community mostly consisting of backpackers in Alaska and Tasmania to people from all over the world – potentially anywhere that you can find runnable rivers that are accessible by foot. In more recent seasons, my feed has exploded with river footage from all across the US, Central America, Russia, Austria, New Zealand, Lapland, Scotland, Japan, and on and on. Which in one sense is great to see so many new people discovering what packrafting has to offer. But as the community continues to grow, so does the likelihood of mistakes, injuries, and fatalities. To date, there are twelve fatal accidents recorded that relate to packrafting.

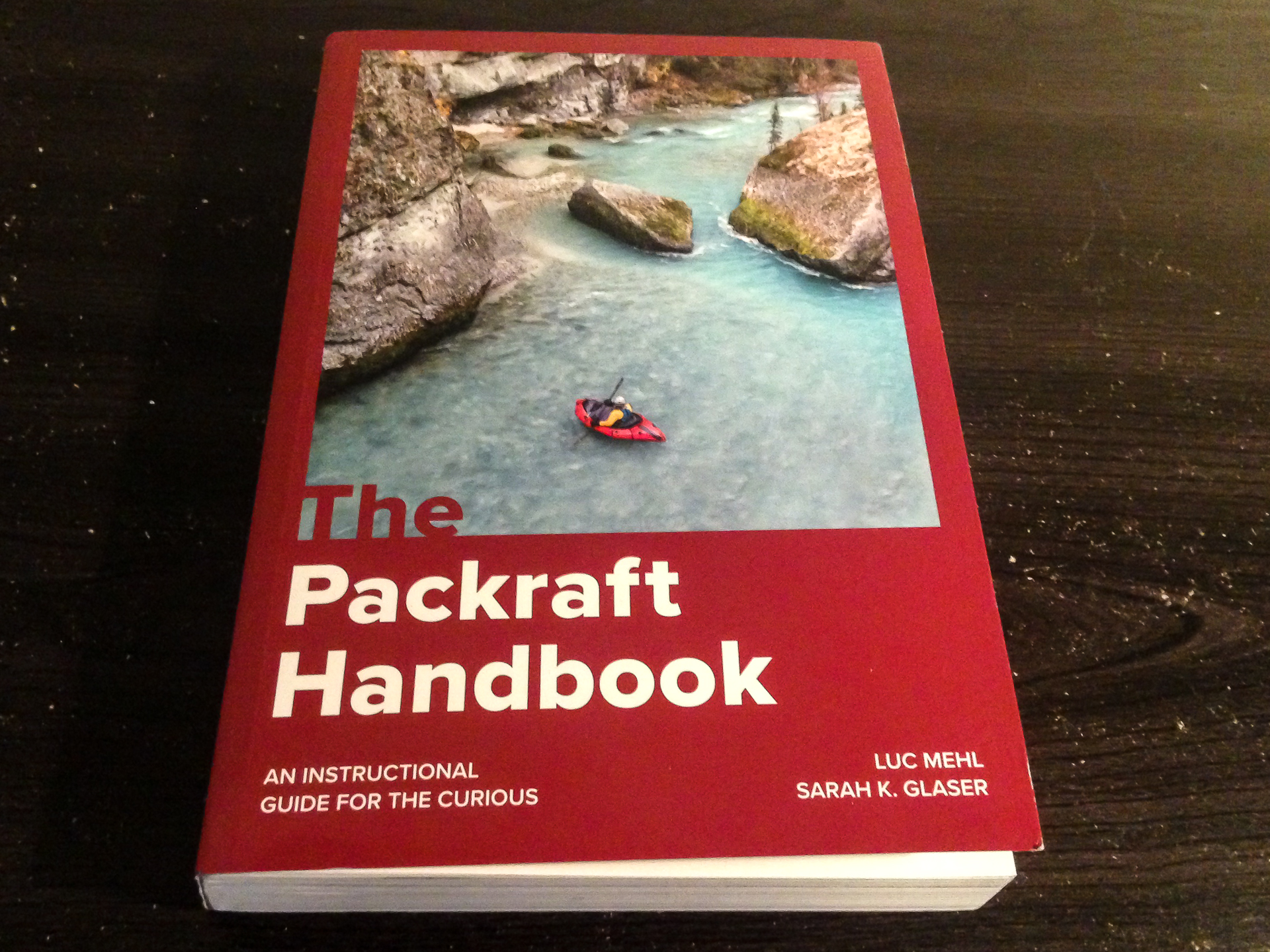

In response to this increasingly important issue, Alaskan boater Luc Mehl published the Packraft Handbook in June of 2021, which is a comprehensive guide to amphibious river running. With the help of illustrator Sarah Glaser, this book provides a very detailed yet simple guide to everything a boater needs to learn – from preparation, to paddling technique, to capsize recovery, and swiftwater rescue. Which I feel is long due in this community. Because while packrafts are generally very stable and forgiving as watercraft, they have given many boaters – myself included – a false sense of security to run bigger rivers where we had no business going without proper training.

It was Luc’s goal to change that trend with this book. By adapting many of the river rescue techniques already developed in the kayaking community to that of packrafts, the book encourages a #cultureofsafety as its core ethos – a community where we can continuously educate ourselves and others on the importance of river safety.

The book is divided into four parts, the first being Foundations. Here, Luc describes the types of packrafts available, equipment, boat control techniques, wet entry, and risk assessment. New packrafters especially will benefit from the knowledge it offers on how to get started.

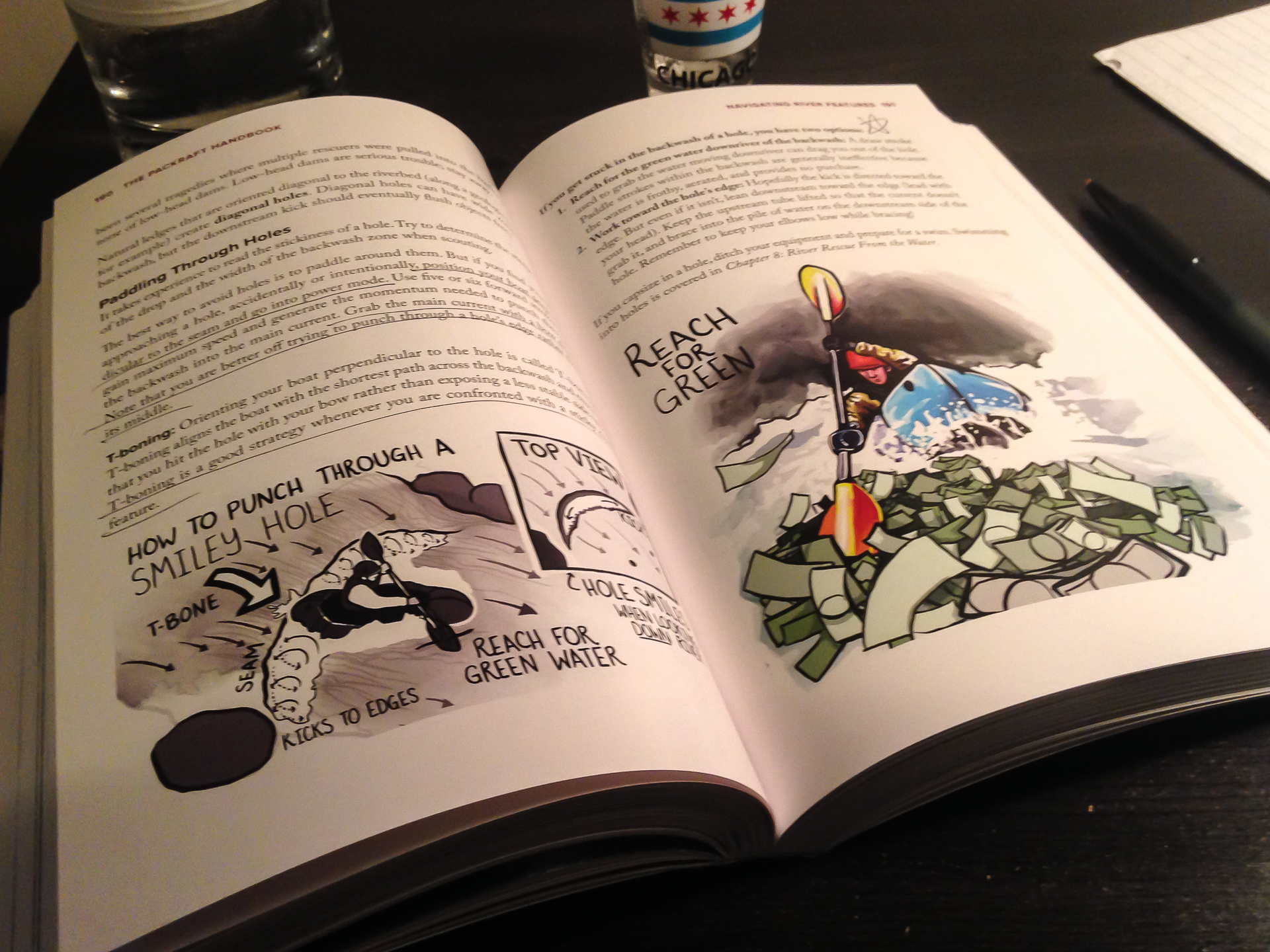

The second section, Rivers and Open Water, explains the basics of navigating different types of rivers and open water crossings. There are different types of paddling environments with risks inherent to each. Technical swiftwater is different from a windy fjord crossing, but both can be dangerous. It is important to be experienced and prepared.

In the third section, When Things Go Wrong, Luc describes many different types of accidents and the proper rescue response to each, detailing things like self-rescue, throw ropes, entrapment, rolling a packraft, equipment repair, and various examples of First Response emergency treatment that hopefully won’t be needed. I think this section is truly the meat of what we need to understand out there.

And finally, Part 4: Putting the “Pack” in Packrafting has two chapters about planning and logistics. Because it is easy to overpack when you already have to carry ten pounds of river gear. But at the same time, you don’t want to cut too many corners and underpack supplies that you might need, like say, a first aid kit.

It makes me wish I had thought about this four years ago when I made the mistake of running a scary glacial river in Iceland. It was a mile-long river connecting two lakes close to the Jökulsárlón Lagoon in the south coast, and appeared friendly on the satellite. I crossed the first lake and started down the mouth of the river, which was swift but calm. Before I realized it, the current started picking up into a Class II section and I was flying down a center line. Suddenly, I was seconds away from dropping over a river-wide pourover ledge of four feet. And a big hydraulic. With no time to find the line, I charged at it unsuccessfully and got tossed out.

And then I froze. Not literally, but mentally. For about two minutes. Flying down a river.

I thought I could kick my way to an eddy, but the current was too strong. Another rapid was approaching. I snapped out of the fog, threw the paddle across my boat, and lunged forward. I climbed back in and regained control, navigating the breaking waves. Ten seconds after I recovered, I went flying past what might have been a pinning rock.

I had originally planned to run another Class II-III river the next day, but realized as I got to shore that I needed proper rescue training and other partners before attempting something like that again. It could have ended differently. I could have died.

I could have died.

The good news is this this book can give you answers wherever you’re at with your skill level. In my case, I needed more practice at wet exit and recovery. A lot more practice. To the point that it becomes second nature to fall out, flip the boat, and jump back in. I also needed to recognize a wild river when I see one from the satellite. And most importantly, to never go alone on a river like that again. To quote my friend Ben on a similar note, “I lived and I learned.”

Since that trip, I have only done solo trips on easier Class I-II rivers in the Midwest and east coast, usually at the end of the summer when the levels are low. Appalachian rivers like the Shenandoah are nearly all pool-drop flows, allowing for easier recovery between the rapids. And many of them are commercially run, meaning that outfitters are already proactively clearing them of strainers and debris, for pretty obvious reasons. But still, I remind myself that paddling solo will always make me inherently more vulnerable to accidents, and that I need to be extremely cautious. Also, I won’t be running the Gauley in my raft.

But most importantly, I’m due for a swiftwater rescue course – for the benefit of myself and others.

In scuba diving, they teach us that the primary objective of any dive is always to get everybody back safe and unhurt. This is my primary goal of any river trip – for myself and the others to get through it safely. The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl explains how. From novice to veteran, boaters of all skill levels can benefit from the knowledge that it offers. So let’s make the #cultureofsafety a worthwhile goal this paddling season.

https://thingstolucat.com/packrafthandbook/

https://swiftwatersafetyinstitute.com/ssi-courses/

Parting Words on the Harding Icefield

Parting Words on the Harding Icefield

…continued from The Shores of Kodiak Island

I was set to fly out tomorrow, finally, after two unforgettable months in the Last Frontier. My life in the great north, like all great things to me, was part of a cycle. Profound, life changing, impossible to fully articulate, the wonder of this country abounds. But it is nonetheless finite and constrained within the limits of time. Whatever I could get out of this had to be now. These were my last fleeting moments of solitude and escape in the great country of Alaska. I would find whatever is left for me on the edge of the Kenai Fjords National Park.

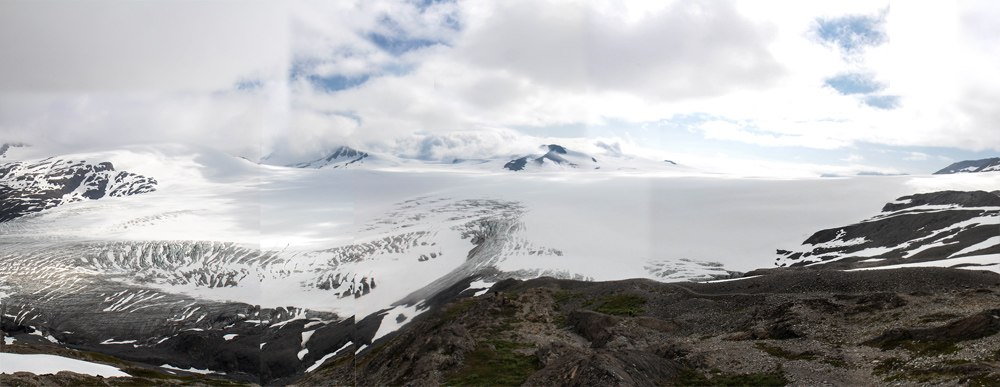

Known for its 38 glaciers and numerous fjords along the south coast, the park encompasses a huge section of the Kenai Peninsula just west of Seward. It is a two hour drive out of Anchorage to the trailhead of the Harding Icefield Trail, a steep four mile climb of 3,000 feet to the edge of the Harding Icefield. From there, hikers can see across a huge 300 square mile field of snow.

I arrived in the late morning. The welcome center is nestled between high, steep mountains with the view of the Exit Glacier ahead, cutting out from the snowfield high above. I started on flat ground, hiking past groups of tourists through the dense alder and cottonwood forests of the valley floor. Soon, the trail went steeply up the ridge. It switched back and forth up the mountainside, occasionally flattening just enough to cross a rushing creek. At times, it was so steep that they had to handcraft staircases out of rocks. Nonetheless, it was well maintained, given all the traffic it gets in the summer.

Eventually, the trees thinned out and I could see the valley floor, 2,000 feet below. I’m leaving all of this behind tomorrow. For two months, I planned, I explored, I rode, and I paddled. To find out – only if even for an instant – who I am in my most memorable moments of solitude, adventure, excitement, reflection.

I hiked on, exhausted, up this seemingly endless four mile climb. Hard as it was, the view of the glacier, the valley behind, and numerous lupine and fireweed patches distracted me just enough. Soon, I walked along a huge scree slope across occasional patches of snow. The massive Exit Glacier descended down the valley to my left. 500ft ahead was an emergency shelter. If the weather were to take an unexpected turn, as it often does out there, hikers can find refuge in there to wait it out.

Finally, I reached the ridge above the snowfield and the end of the trail. There was snow as far as the eye could see.

This quiet, frozen landscape marked the end of the most meaningful trip of my life. I set up my camera and tripod, pointed it at the far mountains, and timed it to hit every 5 seconds. To the sound of the clicking shutter and cool breeze along the ridge, at last, I got out a notepad and began to write.

I’m on the edge of a vast wilderness of ice, snow, wind and stone. As I watch the clouds roll across the ridgelines of the snowfield, I feel like this is going to be it for a while. I spent four years of my life obsessing over Alaska. It got to the point where people started asking me if I was going to move here. I don’t see that happening, but I did need two months to at least try to be satisfied. After hundreds of miles and pictures, I think I finally am.

This all began on my computer four years ago. Mere photographs made me curious about the Alaskan country. I ended up going on three bike trips that summer, and remember feeling profoundly changed by each.

I remember the first time I saw Denali on a clear morning. I came over a hill after a night of hard riding, and saw a huge, immense mountain of granite, snow and ice, carving into the morning sky in resounding glory. It wasn’t just a memory – it was a life changing catharsis. It showed me a love for the wild country that I never knew existed.

Since then, whether by bike, train, or some other way around, I have made it my lifetime goal to find and capture as many experiences as I can. I have been a lot of places in the last four years, but Alaska was always on my mind. I needed to come back. I needed to finish what I started. I finally feel like I have, and it’s time to go home.

Thanks for reading! This story begins in Denali National Park.

The 450 Tour Part 3: The Richardson Highway

Two major highways meet at the junction at Glennallen. It has one gas station, which gets a ton of business in the summer. Most people stop there because there isn’t much else around. There were two bathrooms, and one of them was out of order. So a lot of tourists waited in line to use the other one. I had to use it because I didn’t want to take a dump in the woods earlier that morning (honestly, how often do any of us shit in the woods?), and didn’t know where else to go. Nobody was waiting when I went in, and I tried to go as fast as I could. I came back out to a line of four people. Well, time to get my bike and keep going.

This was the third and final phase of the 450 tour: The Richardson Highway. Here, I would head south along the Copper River Valley for 20 miles, camp out at the Tonsina River, and then take the next day to climb over Thompson Pass. The ride would end in Valdez, where I would stay the night, and then take a Whittier-bound ferry across the Prince William Sound.

I started south. The mid-afternoon sun blazed in the northwest as I rode along the bluffs of the mighty Copper River, looking out when I could at the vast mountains of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. Its peaks range from 12,000 to 18,000 feet, reminding me of the Cascades of the Northwest. Originally, I thought to incorporate a 2-3 day packrafting trip down the Copper River to Cordova, somehow rigging my cycling gear on the raft. When I read that this river has its share of dangerous eddy lines and katabatic wind-driven sandstorms downstream (yes, there is shit like this in Alaska), I decided on the relative safety of the highway instead. But even that wasn’t entirely safe, as I would be flying down a mountain pass tomorrow.

I had one huge hill to clear before a steep descent to the Tonsina River and somewhere quiet to set up my tent. I camped outside of the Russian owned Tonsina River Lodge, fueling up on meat, beer, and caffeine. That night, the 4am sky glowed in what was already a new day in the boreal summer.

I started before the sun came over the mountains. It was supposed to be another hot day on the coast, which doesn’t happen often. I lucked out this summer, as a lot of my outdoor trips ended up having great bluebird weather. Hot as they often were, I would take that over cold rain and fog any day. Though in its own way, I found, the rain and dark clouds can also bring out the richness and magic of the mountain country.

The climb was mostly gradual for 20 miles. The next lodge where I planned to top off my water was closed. I climbed another 5 miles to the next one. Also gone. Fuck, I guess I have to ration what I have over the pass. I didn’t bother bringing my filter, the clogged, worthless piece of deadweight. The road was often steep in places, but manageable. I was surrounded by the huge, steep mountains, with summits carved out by icefalls and glaciers. On any cloudy day, I expected none of this could be seen.

Near the top of Thompson Pass, the Worthington Glacier claws steeply out of a mile high ridge system. I could stop and check it out, or I could worry about refilling my damn water. I had half a bottle left, and was betting on something at the bottom of the other side. There were two more miles to go in the hot alpine sun before reaching the summit. I made it there and looked around the mountaintops, which spread out in a full panorama. Here, the highway descends steeply for 2,600 feet to sea level. I looked at the descending road ahead with a familiar sense of foreboding.

The top of any big bike descent, or river rapid, or scuba dive, always drives me treacherously out of the boredom of my comfort zone and into the thrill of the unknown. I never know what is ahead. And I’m not always confident that I can get through it. But I think my fear is what makes me feel even more connected to the wild outdoors. It could mean hitting a rock at 30mph and crashing on the road. It could mean worse. But despite the risks, I’m drawn to it. This road is horrifying, and horrifying is awesome.

I went flying down the top of the pass for a mile amidst huge green mountains and blue skies. The road went around a loop, and kept going steeply down the mountain. I went fast into the grade and headwind for 10 minutes before I reached the top of Keystone Canyon. Here, the tunnel wind blew through the canyon, forcing me to a crawl. I was out of water, 20 miles from the town, riding along the bends and turns of the canyon. At least the scary part of it was over.

I came around a turn to Bridal Vail Falls, then Horsetail a minute later. The cool moisture got to me. Dammit, I need water! I had left my purifying pills with the rest of my gear in storage, because why would I need them on this tour?

The road turned west towards the town after the canyon, and the headwind was unrelenting. Valdez was 15 miles away. I WANT WATER FOR FUCKS SAKE! Finally, I saw a convenience store across from the airport. I drank a liter of Gatorade and sat outside in the shade, savoring the moment. I am hydrating. Life is good.

No longer feeling weak from thirst, I could enjoy the last few miles of this tour. Numerous ragged sawtooth mountains lined the south end of the valley above the Lowe River and the Valdez Marine Terminal, the big oil port across the bay. Yes, that one. This town was in interesting mix of tourism, local fishermen, and oil industry workers. And on this day, the local DOT was making the most of the hot, dry weather to pave the highway. I saw 5 road crews out, throwing down asphalt as fast as they possibly could.

Finally, I got to the town. I checked in at my hotel and arranged for Nickel to pick me up in Whittier tomorrow. I was exhausted, but not enough not to end this tour with a salmon dinner at the Fat Mermaid by the harbor. A guy with a guitar played Jimmy Buffet covers as I ate and watched the colors of the late day change across the water.

I loaded my bike on the ferry the next morning. It would take six hours to cross the Prince William Sound, but I barely noticed as the boat skirted a million waves along the pristine Alaskan shoreline.

This story continues on the Portage and Placer Rivers.

The 450 Tour Part 2: The Glenn Highway

I got my bike and touring gear out of a U-haul storage in midtown Anchorage and went north through the city. I passed by the neighborhood that reminded me of a woman from 2012, who turned out to be the best ghosting story I’ve ever had. We met online and went bar hopping in downtown on what ended up being a good first date. She was a licensed pilot who worked for a local flightseeing company, and halfway through the night she offered to fly me out to the Knik Glacier as an idea for a second date. So of course I’d be up for that. The night went on from bar to bar, and we continued to have a good time. I followed up later to pursue this whole glacier idea further… yeah, ghosted. Like straight up nothing. After talking up all this game, I did not get my glacier, I got fuck-all. On the bright side though, at least we don’t live in the same town.

But I knew if I was going to get through the next 300 miles, there were more important things to worry about than my dating failures, like the downpour that hit me on the outbound Glenn Highway. I rode into a lot of hard rain and shit for visibility. And my rain gear was about as waterproof as a mesh T-shirt. The big problem was that my rear blinker wasn’t working. Luckily, the highway had a huge shoulder. That said, I don’t know how I survived to tell the tale.

I got to Eagle River after about an hour and waited in a shopping plaza for a bike shop to open. I checked my work email. Dammit, one of the client websites was busted. To fix it, I would have to write about 10 lines of code, but I didn’t think I could do that from my phone without screwing it up even more. I realized that I could patch it with one line in the login process to bypass the bad part of the code for now until I can get back to my hotel next week. I was in the site admin panel trying to wipe droplets off of my phone and code it in. On my phone’s keyboard menu, you have to go to submenus to get to some of the characters used in PHP syntax. A pain in the ass. I saved the file and tested. Looks like that got it. People ask me what I do and I tell them I get mad at a computer for a living.

The bike shop opened and I got a new tail light and set of fenders to keep the wheels from flinging mud on the drive train. It was great service from Alaska Velo Sport in Eagle River, and I’d be glad to recommend them to other cyclists going through. I went north as the rain backed off and clouds started breaking on the ridges.

Thirty miles later, I started climbing the eastward hills into the mountains just after Palmer. What the hell is that sound? Something in my drivetrain was squeaking with each pedal stroke. After some investigation, I realized that the guy at REI forgot to put lube on my chain. I didn’t have any chain lube with me, and the last shop for the next 250 miles was in Palmer, five miles back. After that it’s just me and that road. I called the guy there and asked him if there was any possible way they could wait for me to get back at 6:30. He said dryly, “We leave at 6.” Fuck.

I had 40 minutes to get back, but luckily it was all downhill. And I was hauling ass. I didn’t want to risk a chain break over the next few days in the middle of nowhere. I made it in just under 20 minutes. He lubed the chain for free, which was cool. I finally thought I was ready for this tour. I climbed the hill above Palmer again and listened for the squeaking. It was gone.

Ahead, familiar mountains closed in as I climbed along the rush of the Matanuska River. Clouds lifted, thinned out, lightened, and broke away from mountaintops in the late sun. Soon, I arrived at the Pinnacle Mountain RV Park. It was an eclectic place, full of pretty old junk, flower gardens, ducks, swans, goats, llamas, and alpacas. Antique tractors lined the road in a row, some of them with flags. Flower beds had colors that you would never see in the state, clearly built by somebody with an eye for aesthetic design.

When I walked to the outhouse, I kept getting hissed at by one of the swans. I gave him a wide berth of 20 feet, but it still wasn’t enough not to piss him off. Can’t win em all, I guess. But I wondered, how do they protect all of these pets from wolves and bears?

I waited for the lodge restaurant to open the next day. It was my biggest day of climbing yet, and I needed to eat as much as I could. The lodge owner cooked me breakfast and talked my ear off for an hour. This lodge, its antiques, flower gardens, animals, and quirky random things were her creation. She has it exactly how she likes it. And I like that. She was so much fun to talk to that I lost track of time. I got going at 11:30 for the next pass. But hey, it’s going to be a long day. It’s summer in Alaska.

I’ve done this road before. Right after the RV park is a bridge crossing and the first of three steep uphill climbs over the next twenty miles. I pedaled against an incline, gravity, and doubt. Behind, the familiar stoic King Mountain rose above the roar of the river as it made its way westward. The climb at Long Lake was the next big fight, as I paced for a slow hour on low gears. The Chugach Mountains to the south came in and out of clouds and shimmering glare, occasionally lighting up in breaks of sun, only to be enveloped in showers a minute later.

My favorite part of this pass was near the Matanuska Glacier. Here, the mountain ridges curved along the valley above a bed of forest, split in half by a huge glacial moraine whose streams would eventually feed a charging river. It was good to be back. Not just to be back, but to keep going and make this adventure even bigger and more personal.

Soon, I reached the part of the road that I knew and hated: The Caribou Creek Gorge. The road descends for a mile to the canyon floor, crosses the creek, and then goes back up the other side at an 8% grade for a full mile. It’s a real cracker jack of a climb. But I knew what I was in for, and got going slow on the grade at an easy pace. The important thing is to keep your gears low and cadence high. Head down, pedal, and fight it out. It hurt, but I made it to the top after 20 minutes with no breaks and surprisingly no bitching. The Grand View Cafe was just a mile downhill after the top, and was well earned.

It was a slow weekday at the cafe restaurant, where I chatted with a young Latvian lady working there for the summer. She was jealous of my tour. She said she did the same thing last year from Whitehorse to Vancouver, which is bloody impressive. That’s farther than anything I’ve done. I told her she should get back on the road and she agreed.

I continued east out of the range. Clouds darkened over the mountaintops, dumping sheets of rain on the high tundra. The peaks of the Chugach range broke away from the road as I went eastward. Big grey clouds and summer showers rolled across the plains ahead. I made one last stop at the Eureka Roadhouse for food.

At mid-evening, I was flying down a huge series of hills as the road made its way out of the mountains and into a huge plain of taiga forest and a million lakes. And with them, a horde of mosquitoes. I didn’t care. I was living. I crested a hill and saw the alpenglow of 12,000ft snow capped Wrangell Mountains rising high above the plain, 60 miles away. ATV riders rode along a track parallel with the road. I kept up for a second. I pedaled on, glowing amidst a tremendous, gorgeous landscape.

I was in such a good mood that I thought fuck it, I’ll get to Glennallen tonight. It’s another 40 miles, but I’m kicking so much ass. And it’s been years since I’ve done a proper century, on a tour no less. I charged on, high on endorphins, protein, life.

What you don’t see on a terrain map – the one of this area included – is all of the steep river crossings. Even on a straight road like this, which was mostly downhill. Each creek crossing meant a descent and a climb back up the other side, eroding my energy levels faster than I expected. I crossed a river at 11:00 and spent 10 minutes getting up the next hill, finally getting burned out. I stopped for a break at the top, looked at the trees by the traffic pullout, and thought that’s it. It’s time to call it a night. My hubris got me another 15 miles that day.

I set up camp in the woods next to the road and slept under a lavender sky.

I made for the town in the clear morning. The road straightened out and leveled into a gradual downhill coast as I approached Glennallen. Black spruce trees, muskeg, and brushy tundra carpeted the landscape while patches of fireweed flowers decorated the sides of the road. At midday, I passed the town with the blink of an eye and got to the junction and the end of the Glenn Highway. Here, I would head south to the ocean.

This story continues on the Richardson Highway.

The 450 Tour Part 1: The Seward Highway

Whenever I’m not traveling in the country, I like to be somewhere with a lot going on. That’s why I live in Chicago. When I want to get some good beer and fish tacos, I can find them down the street. When I want to meet new people, I can. When I want to go to a festival or a museum, it’s around. Which was why I based my operations out of Anchorage. Because even though it’s nowhere near as big as Chicago, there was still plenty to do in my downtime. I set up my work station out of shitty hotels next to downtown, which made it very easy to find things to do. For two months, I spent my weekdays in hotels working on my company projects, planning my outdoor trips, drinking, or hanging out with women from OkCupid.

CW was an OkCupid fling-turned-friend from 2012 who I have stayed in touch with over the years. We met up numerous times for pizza or food trucks, where I also met her bestie KM. One night we went to the MST3K Reunion at a nearby cinema. The cast of MST3K and Rifftrax broadcasted the event to theatres all over the country via livestream, and spent two hours destroying some of the best stupid-awesome shorts I’ve ever seen. One of the best ones was a video from the seventies about how kids can have fun with grass. If you want to play with grass, go outside and pull some out, and start braiding it on a table. You can use grass to make a mask! Or braid it into a headband! Or make grass earrings! Fun with grass! I hadn’t laughed that hard since my best friend showed me Maddox’s website.

I also had an email exchange with Nickel, and we met up for a bar crawl date in downtown on my first week. And then it became a fling that lasted for my two months there and after. For many evenings, we met in hole in the wall restaurants or local haunts, or did shots and Game of Thrones at her house. Often times, it was the only chance I had to relax between my workload and outdoor logistical hassles.

So when I got back from a two week adventure in Denali, it was just in time for the annual Pride Parade. And who better to call up than Nickel to join me. Cause I wouldn’t say that I’m out or proud, but I wanted to show up and support Alaskans who are. That, and I thought it would be a good idea for a date.

I went by her house late that morning and we left with her roommate Alpha for the downtown parade. When we got there, a big crowd stood on the sidewalks as numerous floats and groups marched down the street. The local VA, school groups, Alaska Air LGBT, and so on. Later, there was a festival in a nearby park with local folk bands and rainbow bracelets by the truck load.

Nickel and Alpha ran into numerous friends, including DD, who has become a force of reckoning on the local interwebs. She told Alpha about a guy who she recently hooked up with on her Tinders. Which wouldn’t be any big deal, except that her reason for hooking up with him was because they went on a date once a while back, and she remembered that he was a nice guy. Only to figure out later that this guy she hooked up with now was a different fucking dude!

This anecdotal gem and many others can be found on her website All the Dicks. After a bad divorce and some soul searching, she made it her goal to find and score with as many young dudes as she can, because fuck it. Which I think is awesome. You can read all about it here (but note, my dear traveler, that what is read therein cannot be unread).

It was fun, but I needed to catch up on my work, and Nickel wanted to hike Flattop with her uncle. We parted ways and I went back to my hotel.

I was up in Denali for the last 15 days, and at the end of the next week, I would be leaving for another 7. So along with catching up on two weeks of work, my boss piled on everything ahead. This included two big software upgrades, which, if you work in software you would know amounts to a dogpile of QA testing, patching, and retesting. All that afternoon and Sunday went into the first rollout. Then for the rest of the week, I was hurdling smaller jobs to get to the other project before the Friday deadline. Somehow I managed to find time to get my bike from REI and a drink with Nickel at Mad Myrna’s.

That Thursday, I was charging into the night with Red Bull and bloodshot eyes, trying to make my deadline on Friday 9:00 Eastern. In Alaska, that is 5am. At 3, I did what should have been a final QA test, only to figure out that there was a whole section that I forgot to add in from a previous draft. I spent the next hour writing a new block of code, which I hate doing when I’m tired. At 5, I finished one last QA run, uploaded, hit the switch, and fired off a one sentence email to the clients, making my deadline down to the minute.

Then I slept for two hours, worked all day on even more of this shite, tied it all off at 5, packed up my computer in storage, went back to REI for a last minute derailleur fix, and packed up my panniers for the train ride out tomorrow. Fucking hell.

Finally, I was ready to do what this is really about: My 450 mile bike tour from Seward to Valdez. If it went as planned, the train would drop me off in Seward, and I would spend the next week riding on the highways to Valdez, and then board Alaskan Highway ferry for the trip back across the Prince William Sound. It was ambitious, cause it’s got to be when you ride like Dan Hagen.

I got out at the Seward depot at noon on Saturday and went north along the highway, planning to reach the town of Hope at mid-evening. I climbed the mountain passes for hours on a well-paved road and big shoulder, often looking out at the big, forested mountains and blue skies. Halfway through the day, a blanket of stratus clouds spread across the land.

The Summit Lake Lodge marks the high point of the pass, where I stopped to eat. After this, it is downhill for two hours to the ocean, starting with a 6% grade into headwind for a few miles to the Hope Junction. What I didn’t know was that at that speed, an 18 wheeler can fly by on the road and break the headwind, creating a powerful vacuum of tunnel wind that would end up pulling my bike towards the road… WOAH, SHIT!!! I almost got thrown into the road as the truck flew by at 65. I pulled away from the wind, fighting with all my strength to keep control. I screamed in horror for the first time in more than 20 years. Remarkably, I kept it together and coasted back onto the shoulder.

I got down to Hope Junction a few minutes later and continued on Hope Highway, relieved to be away from the traffic and freaking out because I almost died. The silence of that slow two lane road calmed me down. Keep going, Dan Hagen, keep going. You’re 10 miles out from food and sleep. And you didn’t fucking die. Not today.

The highway descends from the mountains to the edge of the inlet and sea level. From there, it follows the south shoreline of the Turnagain Arm for 7 miles west before ending at the remote town of Hope, Alaska. There, I would find hot meat and cold beer.

When I rode few miles out on the hilly coast, I looked and saw a wall of rain engulf the mountains across the water. It was heading this way, and I needed to get to town before the shower did. That didn’t happen. The rain hit my face and arms with a mile to go.

I had spent an entire day alone on this highway. I had adapted to the solitude of the quiet forests and closed in feeling of the mountain country. I felt content riding in the comfort of my own thoughts (despite that scary dustup at the junction). So when I came around one last turn to the main street of Hope, I was surprised to see a big crowd of people outside of the Seaview Cafe. On Saturday night, you will likely find lots of people drinking in the bar and patio, reggae music playing, kids and dogs running around, campsites, bonfires, and people cooking meat in the yard. What the hell? I coasted in with a huge grin on my face. This was exactly what I needed. I was glad to set up my tent, get some bar food, and talk to the locals.

“Hey, you got out here on a bike? That’s pretty badass! Where ya headed?”

“Seward to Valdez.”

“Hell yeah!”

After a burger and two beers, I went outside as a local jam band started playing. I was exhausted from the day ride, and the food and beer just about knocked me out. I crawled into my tent and quickly fell asleep to the white noise of live music and local partiers. It was a happy place to be on this big, wild shoreline.

I left for Girdwood the next day. As the eagle flies, it’s 15 miles across the water. By road it’s 50 miles, and the first 30 of it is all uphill until you clear Turnagain Pass. I spent 4 solid hours beating my way to the top before descending back down to the edge of the ocean, 12 miles away from where I left it. Once I got to the westbound side of the highway, the tailwind blew me all the way to Girdwood. I could have opened a sail and coasted. Today, the wind is my friend in the fjord country.

Girdwood has a Forest Fair every summer, where Alaskans from all over the state come together to watch music, buy and sell art, celebrate, and be hippies. I was lucky enough to roll in during the last day of it. This town felt like a mini-Asheville.

A local woman who I met in Hope last night told me I needed to check out the band playing at 5:00. I went to the stage to watch them. It was relaxing after all the hours I had busted ass that day, but I soon got bored and left. They had a clear semblance of the Grateful Dead, whom I have never liked. Besides, I could smell funnel cakes from the food stands, so priorities. I sat down to eat one when I heard the band play a rocked out cover of Pancho and Lefty. That got my attention and I went back.

Later, I went to the hostel, a homeshare in the residential part of town. An old lady greeted me and showed me around. She let me hang up my tent in the back yard to dry. I sat on the back porch, and she came out and told me that the porch was off limits to guests. Okay. I moved to the front to eat while my tent dried. The daughter, who usually manages the hostel, came by for a few minutes to talk to her. From what I overheard, something was up. The daughter left. Then the woman told me uncomfortably that her friends would be coming back soon for a barbecue, and I had to move all of my camping gear to the front, and that the back yard is actually off limits to guests anyway. Awkward much?

Look, I get it if you want to make money out of your house, but get your boundaries sorted out, people. I was polite and did what she asked, but I won’t be going back there again. Not that I plan to go back to Girdwood anyway, but you know what I mean.

It was all grey skies and fireweed from here. I rode a solid 40 miles along the coast and got back to the city in the late morning. I had some extra time to sort out my gear and get my computer out to make sure everything was okay while I was gone. I checked my work email. Nothing from the customers. Good. No news is good news.

Later that night I stayed in a HI-Hostel in Spenard, where unlike the one in Girdwood, I was allowed in the back yard. It was the 4th of July, and they were having a barbecue. I met an old guy who had lived in his RV for 10 years, a man who met a lady in Florida on his bike 16 months ago and they have been riding ever since, a young girl from the Chicago suburbs working in Alaska for the summer, and a dude my age with a 3 year old daughter who knew she was the cutest person in the whole place. And then there was me, the guy riding his bike from Seward to Valdez.

We drank and hung out as bottle rockets echoed across the city. The Chugach Mountains turned purple in the late evening sun. Fireworks continued to bang into the night.

This story continues on the Glenn Highway.

Glacier Discovery by Packraft

It was a sunny weekend in the Anchorage area, and I couldn’t pass up the chance to paddle the cold, charging rivers of Alaska, where the sport of packrafting was born. Just southeast of Anchorage, the Portage and Placer Rivers flow out of the Kenai Mountains to the mouth of the Turnagain Arm, making an easy scenic river trip for the local paddler. These rivers are both train supported, utilizing the Alaska Railroad’s Glacier Discovery line, which will take you within hiking distance of each river launch.

The beginning of each river is the end of a stunning lake, each with its own respective glaciers that carve out of the high mountains, creating a more dynamic lake-to-river boating experience. I wanted to do it all. Because Alaska. I packed my raft, camping gear, and a big box of Pop-Tarts for the weekend and boarded the train on Saturday morning.

Saturday: Spencer Lake and Placer River

9:45am – Depart from Anchorage

1:45pm – Get out at Spencer Whistle Stop, hike 1.3mi to Spencer Lake

2:30pm – Paddle Spencer Lake and Placer River 15mi to highway bridge

6:00pm – Hike 3mi to 20 Mile River and set up camp in the trees

Unlike the other train lines, Glacier Discovery is more specialized to assist in short day trips around the Spencer Glacer, Whittier, and Portage. The train got to the Spencer stop at midday and a group of us got out to raft downstream on commercial boats, kayak on the lake, or hike the trail system.

I hiked out to the edge of the lake, where at some point a glacier calving caused icebergs to float across and beach on the shore. The water was still on the calm day, reflecting the blue face of the Spencer Glacier from across the lake. I suited up and paddled out, maneuvering around several icebergs on the south edge. Soon, I found the river and went for the current. Up ahead, the roar of the rapids made my blood go cold.

It’s always the same. A new rapid is always a daring venture into the unknown to me. My fight against the currents in the river is just as real as the fight going on in my head. Can I get to the bottom of all of this chaos, overcoming the rapid and myself along with it? Will I crash into a mess of rocks and raging water, or will I clear the last standing wave like a rockstar? Go right for the throat, adventurer, with your game face and bright eyes blazing. It will probably work.

I read that these rapids are a fast Class II, and I definitely agreed as I moved around several big rocks. It mostly channeled down the center, so the line was easy. Soon, my fear changed to a familiar afterglow of excitement and relief as I floated out to calming water. I got this… the Placer ain’t got nothing on me.

Up ahead, I saw numerous trees in the river. That’s not good. Wash up against a strainer in water like this and you’re in trouble. Once I got closer, the river started braiding into smaller channels. I realized that the trees were mostly beached on gravel bars, safely away from the water. I figured they would be, seeing as this river is commercially run. I wouldn’t be out here alone if it wasn’t.

For the next hour, I had fun navigating the fast braid system as the river charged its way out of the mountains. Eventually, I floated back into a wide channel, peacefully going out of the valley to the highway and the edge of the Turnagain Arm. I packed up and walked north towards the 20 Mile Bridge.

A few minutes later, somebody saw me walking and offered a ride. It was 3 women from Anchorage who also just got done packrafting the river.

“Hey, I think we saw you up there on the rapids.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah, we put in right after them.”

“Sounds like you guys missed the party!” I wouldn’t blame them, though, especially if they were new to swiftwater. Those rapids looked a lot scarier when I scouted them than they turned out to be. Work your way up to it, erring on the side of caution, and you live to rock another day.

They dropped me off at Portage and got in their cars to go back to Anchorage. Ideally, Portage would be the place to park your car, get on the train, and get out at the top of the river. I set up camp in the trees and slept by the riverside of 20 Mile.

Sunday: Portage River

11:35pm – Get on train at Portage

12:05pm – Get out at Whittier and hike 4mi over Portage Pass

2:30pm – Paddle 3mi to end of Portage Lake

4:00pm – Paddle 8mi on Portage River to Highway

6:00pm – Hike 1mi to Portage Depot

7:20pm – Train to Anchorage

9:30pm – Steak

My Sunday trip was harder, not because of the river, but because of time. I had to traverse 16 miles in 7 hours – only a third of it by foot – to get back to Portage for their last 7:20 stop. I got to Whittier at noon and made a hard pace for the Portage Pass trailhead. From there, the trail was a steep 2 mile scuffle to the lake on the other side.

That lake, let me tell you, was awesome. It was walled in by steep mountains with the crystal blue husk of the Portage Glacier descending out of a snowfield on the far edge. If I wanted, I could have paddled a mile across for a closer look. I made for the river instead, trying to beat the clock.

It was just over 3 miles to the end of the lake and the mouth of the Portage River. That lake was a test of my patience, with unpredictable ripples and wind slowing my progress. Without a current, everything is slow in a packraft. Nonetheless, the vista was amazing, with the giant Portage Glacier standing to my left. And to my right, the huge, steep wall of Mount Mayor towered above the shore. As I passed it, I counted 8 waterfalls cascading down its slopes, a few of them splattering onto the lake. I made it to the far end in the same time it takes to watch Terminator 2, got out, choked down another Pop-Tart, and got going 20 minutes ahead of schedule.

It was great to be back in a current again. The first couple miles were fast, easy Class I riffles, never getting worse than an occasional rock about 20 seconds away. It was definitely the easier of the two rivers, as the fast current flattened out about halfway through. Near the end, the river meandered out of the valley and into slow flatwater – what I like to call a Midwestern Bathtub. The good thing was by that point you’re pretty much done. I packed up at the highway bridge and got to the Portage Depot with 40 minutes to spare.

When the train came, the attendant got out and said “Hey, you made it!” I did, and I felt like a badass.

The Glacier Discovery train makes the shuttle support easy for packrafting – something the paddling scene up there already knows. I ran into 3 groups of people that weekend who were doing the same thing. If you don’t have a packraft, you can still sign up for a guided rafting trip down the Placer River when you buy your train ticket. All supported, all Alaskan.

Those were some great rivers, but I would have to say the highlight of my weekend was the T-bone steak I got at the diner next to my hotel. Only a hard weekend in the Alaskan country could have made it taste that awesome.

This story continues on The Shores of Kodiak Island.

The Shores of Kodiak Island

The Shores of Kodiak Island

…continued from the Glacier Discovery Packraft

Kodiak, the emerald isle of Alaska, is a lush, enchanting, and ragged island in the middle of a vast grey ocean. It is part of an archipelago south of mainland Alaska, remaining largely remote and unchanged other than a ring of coastal villages and fishing towns. There is one highway system on the northeast side of it that goes for 56 miles of rugged coastline, rendering the rest inaccessible except by boat or plane. I flew in from Anchorage for the weekend with my bike to see what this road was made of.

It was raining when we landed that afternoon with clouds of fog covering the steep mountains above the town. A cab dropped me off at the U-haul, and I noticed right away that this area doesn’t have the same wave of tourism in the summer as the mainland coast. It felt like a real, honest as shit fishing town. I’m going to like it here.

I loaded my bike box into a U-haul van, drove to a campground, set up camp after the rain backed off, and went back into town for supplies. But first, I needed a drink. The Kodiak Island Brewing Company looked and felt like an old saloon. And I bet if they ever read this, they’ll probably argue that they are a saloon. With a sawhorse bar and benches, the smell of old wood and brewing malts, and country music in the speakers, I thought that all it was missing was a layer of sawdust on the floor.

I got a big glass of something good and malty and talked to a few locals. To my left, people were talking about some guy they knew who caught a 100lb halibut yesterday. I figured a lot of fishing stories probably get back here.

After dinner, I went to the town Walmart to get supplies. But there was one important thing I needed to do first to truly feel like I experienced the ultimate. Several years ago, I read on a travel website that they have a bear in the Kodiak Island Walmart. And it wasn’t enough for me to see it in Google Images. I needed to find this bear in person, alive, for myself, and gaze upon its frothy glory. Once and for all, this would be the apex of all that was Kodiak to me. Everything else could have failed, and I would still be the winner. Traveler, give me a badge and a golden star, they do indeed have a bear at the Kodiak Island Walmart.

I left with my weekend supplies, proud of myself and all that I have accomplished.

Later that evening, the clouds lifted and all was clear, save the breaking fog on the mountaintops. I got on my bike and started for Anton Larson Bay, an inlet just over a mountain pass to the north. I made a steady, gradual climb uphill for 5 miles before hitting gravel at the base of the pass. My road bike is tough, but I’ve suffered enough dirty bastard roads to know that it wasn’t worth it. I coasted back down to camp and hoped for better luck tomorrow. But not without a quick side trip to Womens Bay. Because, why not, it’s nice out.

I set out again the next day, aiming to reach Fossil Beach, 40 miles and several ridge crossings south. Let’s see if I have the patience for 80 miles today. A blanket of stratus clouds had already enveloped the mountains again, promising to make this ride altogether more challenging. I rode back over the first hill to Womens Bay, crossed a flat river valley and made my first steep ascent up the other side. This seemed to be the pattern for the entire ride. Flat, wide river valleys punctuated by steep coastal ridges, winding rollercoasters, and unpredictable topography. Somewhere in the middle of it, fog and rain hit, limiting visibility to 50 yards. Waterproof gear, my ass.

After a couple hours of steady rain and steep climbing, I got to the Old River Inn, a lodge situated at the only road junction on the highway. I made it at noon, just in time for their restaurant opening. Some guy saw me and said, “Nice day for a ride, huh?” Yeah, it’s a real cracker jack of a day.

When I came back out, I was faced with a decision. I had 16 miles to go over one last big mountain pass to Fossil Beach, awesome though it may be, was more than I wanted to do in this shit weather. Should I head back? I weighed it, remembering other trips where I got focused and kept going, and it turned out to be the right thing. In this case, the clouds made my decision for me. To the south, they started to break and lighten the forests. Got it. Keep going.

The ride from there to Pasagshak Bay on the other side is 8 miles, and the meat of it is very steep. I pushed uphill for 30 minutes before breaking out of the tree line for a minute, and then plunging into maddening descent. Soon, I was back at sea level, passing horses and cattle ranches along the south shore. I’ll be damned if they have ranches out here.

I thought I was done climbing. No, there was more. Fossil Beach was on the other side of another ridge, and I had to clear another hard switchback at the start. For fuck’s sake. After that, the road went steeply up and down creek crossings, wearing me out. I saw the cliffs going out to Fossil Beach ahead, amidst gales of misty rain and the roar of the ocean. I had to climb yet again to get uphill from the shore, started, and at about halfway up I decided all at once, no. The glimpse of it looked amazing, but I don’t regret my decision. My imagination will do the rest. I turned back.

I got to my limit as I climbed back over the pass towards the highway junction and the lodge. I still had 30 miles of relentless climbing to go before I could dry off at camp and get to sleep.

When I stopped for food at the restaurant general store, I was getting out my wallet when a golden retriever came up to me, wagging her tail. I always like it when a dog comes out of nowhere and wants to be my friend. I didn’t know her name, so I named her Daisy. I came back out with a bag of Cheetos and a soda and sat by the entrance ramp to eat. When she heard it, she does what any dog does when they hear the rustle of plastic. She ran up to beg for people food.

I didn’t know this dog, and didn’t want to be some random jerk outside giving her food, so I kept eating. Sorry, Daisy, those are the rules. I tried to tell her this, and she just got more excited. At one point she went down the ramp, found a rock, and started nudging it with her nose. What the world is she doing? She picked it up, carried back, and dropped it right in front of me, and said with her eyes “Look what I brought you! Can I have a treat?” She’s definitely got the whole cute begging thing down. Sorry dog, you got spirit, but rules are rules. I’m sure it’s not easy being a dog outside of a lodge restaurant, but from the look of her, I’m sure they spoil her pretty well. I wished her farewell and got back on the road.

I rode across a flat valley for 3 miles before reaching the first of two big ridge systems between me and my tent. This one started at a 10% grade. As soon as I looked at it, I thought, fuck you. 20 minutes later, I was at the top, legs burning from a steady cycle on high cadence. It felt just like my gym back home. Once I made it, I had an epiphany. That for all of my bitching, so much of my grief can be dealt with by just eating more throughout the day. I wasn’t getting exhausted so often for reaching my hypothetical limit, but because I just needed more fuel.

I made it through the next few hours with renewed strength and good pace. The last few miles to camp were in a complete downpour. Let’s do this, you wild, ragged island.

Next morning, I tried to check in my luggage at the airport, only to find out that I couldn’t do it until 3 that afternoon. With the extra time, I drove up to Fort Abercrombie, a now decommissioned naval base and historic landmark north of the town. Many of its bunkers are still intact and it has a scenic trail system along the shoreline.

My favorite spot was along the rocky coast of Miller Point. I came out to one of the overlooks and look who I found on a spire thirty feet away.

I had just enough time for two pictures before he fired off an eagle turd. I started laughing, it spooked him and he flew off.

Soon, I was flying back across the Cook Inlet to Anchorage to start a work week, then bigger things on the mainland. But I wouldn’t say that I saw very much of Kodiak that weekend. Not even close.

If you like friendly Alaskan fishing towns, check out Kodiak, get a stouty beer, and try to stay dry. And you might even meet a friendly dog or two.

This story concludes on the Harding Icefield.

Flightseeing Denali with K2 Aviation

Denali National Park from the sky. This was like nothing I had ever seen. I went on a flightseeing trip over the majestic snowcapped mountains of the Alaska Range. And only from the air, I learned, do you truly feel the immensity and scale of the high places of the world.

It was mid-morning and my last day in Talkeetna. I signed up for the earliest flightseeing trip out with K2 Aviation, hoping the beat the low pressure system that was in the forecast later that day. The last few days have been clear, but this might be the last window I had before the mountains were once again shrouded in clouds and blizzards.

The pilot, Mike, greeted us at the airstrip, gave us a brief orientation, told us where the survival gear was on the plane, and had us board a small red 10 passenger plane next to the runway. We each put on headsets, and soon the plane lifted off of the ground. The trees below became a huge green carpet as we flew northwest across the silver braids of the Susitna. Up ahead, the high mountains slowly closed in.

Soon, the spires of the Tokosha mountains were directly below us, split by glaciers and icefalls. We flew across the huge arms of the Tokositna and Ruth Glaciers and into the Great Gorge, a section of the Ruth Glacier boasting granite walls of 4,000ft of sheer relief. Up ahead, Denali, Mount Hunter and Mount Foraker slowly approached under a thin band of cirrus overcast.

Mike named off each mountain and glacier and we asked him questions with our headsets. He pointed out the Kahiltna Basecamp far below, where mountaineers were gearing up for the first stage of a Denali summit. Numerous tents and people could be seen dotting the white blanket of the glacier.

We circled back and made for the Ruth Amphitheatre, a large snow covered section of the upper Ruth Glacier, and a popular landing site for the flightseeing trips. When I got out, the panorama was fantastic. High, ragged mountains, ice and snow surrounded us as we walked around the plane taking pictures. All while plane after plane landed and took off from the makeshift runways.

As we flew out, the lower Ruth Glacier was laden with thousands of crevasses, like the scales of a giant fish. I asked Mike how far down they can go. He said they can often be up to 200 feet deep. This was a wonderful, hostile wilderness that ultimately must be respected and remembered.

Soon, I was back in Talkeetna getting food and boarding the southbound train for another adventure. Whether by ground or by air, my two week visit to Denali National Park was the trip of a lifetime.

This story continues on the Seward Highway.

Cycling Petersville Road

I spent a rainy day resting in Talkeetna, a tiny forest town with a handful of cross streets and one general store with most of the supplies I needed. In the summer, it has large crowds of tourists, backpackers, and mountaineers staging to climb Denali. The hostel was just down the street from the airstrip, where flightseeing companies take tourists out to glacier landings, or drop off mountaineers and supplies at the Kahiltna Basecamp.

Some of the climbers stay at the hostel to work out logistics. That night, I met Alistair, a mountaineering guide who leads people up Denali for a living. I didn’t originally want to do it because of the price, but he was the one to convince me that a flightseeing trip over the range with K2 Aviation would be the best flight of my life. I figured he was right, and took him up on the idea. First, though, I wanted to do my bike trip up to the foothills.

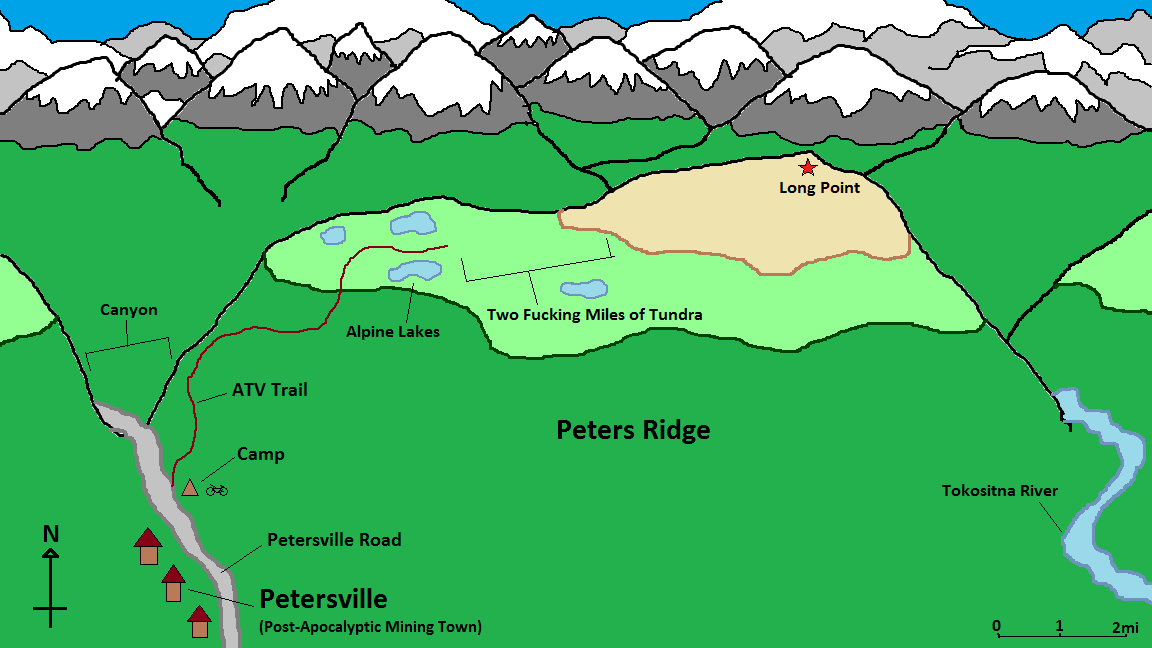

With 15 years of experience and a career based very largely on predicting Denali’s weather patterns, it was Alistair’s professional opinion that the rain would clear out late tomorrow, giving me a window of about 3 days to see Denali. So if I played this right, I would ride my bike for 60 miles from Talkeetna to Petersville tomorrow in the rain, hike out the next day to Long Point on the summit of Peters Ridge amidst clearing weather, come back to Talkeetna on the third day, and on the fourth, I would go on the flightseeing trip, yielding plenty of Instagram-worthy shots of the mountains like the self proclaimed Like-whore that I am.

I was game for all of it. As expected, the ride out from Talkeetna the next morning was one really long series of downpours. I rode 35 miles from Talkeetna to Trapper Creek, completely soaking wet. From there, I turned west on Petersville Road for mountains and hard times.

As the sole pathway into the south foothills, it once served as a road leading to gold mines dated as far back as the late 1800s. Now it’s mostly used by locals to hunt, fish, ride ATVs, or work the privately owned mines for their own killing. I was going out there to climb up to Long Point, the summit of Peters Ridge, which has an awesome view of Denali from the south.

After 10 miles, the pavement ended and I was sliding on fresh gravel. I could use bigger tires for shit like this, I thought, but I managed. Rain continued. The road mostly went through forests with a lot of steep creek crossings and gradual gain as I made for the mountains. The inherent raggedness of it aside, the road was well maintained in the summer.

The rain finally let up with 20 miles to go when a local guy on a mountain bike caught up with me. We talked for a while and he told me all about the nuances of fishing rainbow trout, none of which I can remember. He pulled off to a nearby cabin where he planned to stay and catch something tomorrow.

After a few miles, I descended a steep creek canyon and reached Petersville, an old mining town on the edge of the range. There were seven houses, only one of which appeared habitable. The others were dilapidated and boarded off – decaying before the backdrop of the ridges and dark clouds of the day, like a post-apocalyptic mining town. It was pretty sweet, I’m not gonna lie.

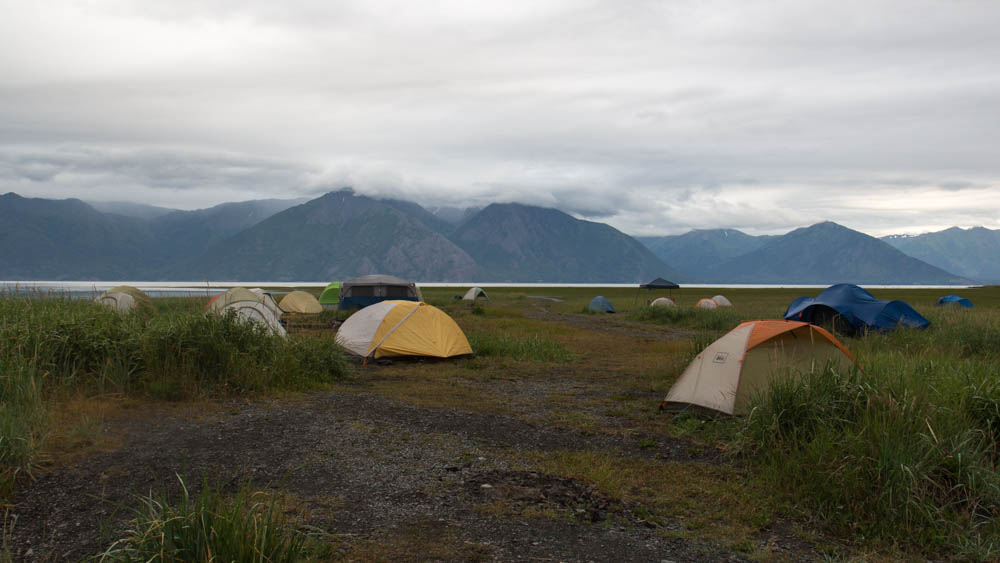

I came around a turn and saw the ATV track to my right, marking the climb I planned to do up the mountain. It was very steep and muddy from the rain. Anything short of a fatbike wouldn’t have a chance in hell of climbing it. And I couldn’t carry all of my gear in my hands either. All I could do was set up camp next to the trail and head up tomorrow with a lighter pack.

When I started the next morning, it was still cloudy but pleasant. I hiked up the steep face of the ridge as the valley behind came into clear view. Soon, I was hiking out of the woods and into the tundra. The trail wound about the steep curves of the high ridge, and was a lot tougher than I expected.

I got to a section of ponds, marking the first four miles of the hike. I tried to filter water here, but my filter got clogged yesterday at the creek next to my tent. It still worked, but would only filter a few drops at a time at a rate of 15 minutes a gulp. Two water bottles is enough for a day hike, right?

Soon, the trail faded into a field of spongy tundra. From here, I had to bushwhack across two miles of the ridge saddle with a few creek crossings and big willow thickets. I learned pretty quickly that the Alaska bush is no joke. It was continuous spongy, knee high tundra, hummocks, and creeks with 8 foot cut banks that won’t show up on a terrain map. It slowed me down big time. And this was just sub-alpine tundra; when you get down to the trees it’s even worse.

I hated to leave my tent at the bottom and venture into this. But the good thing was that I brought a SAR beacon with me on this trip. So if I did screw up and had to get help, I could use it to relay my GPS to a satellite and Search and Rescue, and get a chopper within the hour. One travel blogger who I follow had to do this in New Zealand after he broke his leg hiking in a remote canyon. His SPOT call got him out pretty quickly. It’s reassuring that I have a way to signal distress and don’t need to worry about getting Munsoned out in the middle of nowhere.

There was one last steep climb up to the high ridgeline and then two easy miles out to the summit. The mountains to the north came into view, huge and majestic. Clouds still covered Denali, but there was still plenty to see.

Finally, I reached Long Point, the summit of the ridge. To the north, the icy husk of the Tokositna Glacier curved around the mountains ahead for 30 miles before emptying into the moraine far below. To my right, the ragged spires of the Tokosha Mountains carved into the grey sky like razors. Behind me, the Talkeetna Mountains stood above a huge forest and the snaking bends of the Chulitna River. And far to the south, the Chugach Range and Matsu Valley loomed in the summer haze. I set up my camera for what ended up being a 90 minute shot (edited to about 5 seconds in post) of the mountains and fixed dinner as the clouds blew across the rocky wilderness.

It got to be late afternoon, and Denali still didn’t show itself. I knew that the weather was supposed to clear, but didn’t know how soon. I didn’t want to stay up there, exposed on the high ridge any longer and decided to go back. I trotted down the ridgeline and hacked back through all of that tundra and willow shit. I figured it out later that in that section, I was going one mile an hour.

Close to the end of the afternoon, Denali cleared. This shot reminded me of Stony Hill, the iconic vantage from the park road. Different side, same mountain. I scrambled up one last 30 foot bluff to a familiar rocky outcropping and got back on the ATV trail, leaving the high ridgeline for my tent.

I finally made it back in the mid-evening for an awesome night sleep under clear skies. It was the Summer Solstice, the shortest night of the year.

The next day, I was flying back on the road on a perfect bluebird morning. Several locals stopped to ask what I was up to – probably out of curiosity, and perhaps to make sure I knew what I was doing. Which I understand.

Rest assured, I know it’s tough country, and I don’t want to pull a Chris McCandless out there. I’ve spent years learning how to be as prepared as I know how to be. And like I said, I even have a satellite beacon for the added insurance. And, my dad always knows when I go out on something big, so yeah.

Soon I got to pavement, water, and cellphone service. I reserved a flightseeing trip for the first one out the next day. I saw Denali from both sides of the range. It was time to see it from the air.

This story continues in a little red plane.