…continued from Part 1: Cycling Denali Under the Midnight Sun

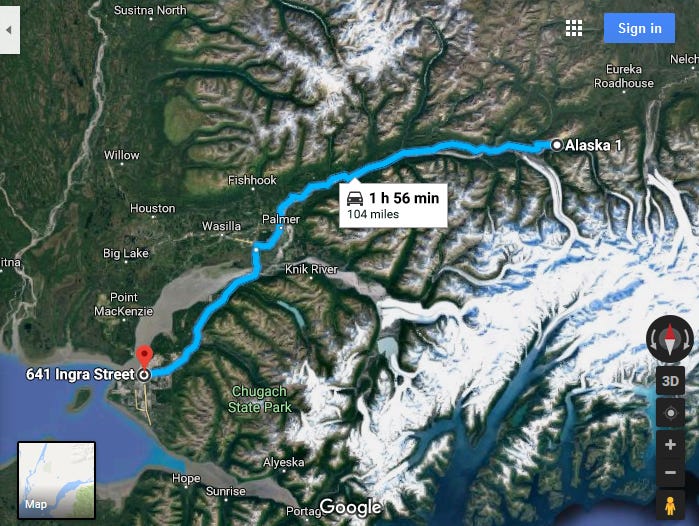

It took me a couple days to feel like a normal person again. That trip really kicked my ass. But I was satisfied that I saw Denali on a good day. It was awesome, and it was done and over with. But I still had two more bike tours planned, the next one being a 104 mile ride northeast up the Glenn Highway to the Matanuska Glacier, a large glacier on the northern end of the Chugach range. The good weather had passed and it was back to rain and erratic, unpredictable weather patterns in the mountains. So I waited for another good window, and in the meantime, got familiar with the bars in downtown Anchorage.

I spent some time emailing women online, because I was curious to know where the good bars were in town.. Since I was visiting from out of town and had some extra free time between bike tours to check out the local scene. And because I was curious to see what else they like to do around town. And then maybe one or two other random questions about their profile, and maybe if they were up for the randomness of it, meet up for a drink at a classy local establishment.

On that note, I noticed that the drinkers up there were some rowdy people. I was out with a lady one night in downtown, and a local guy next to us explained to me that a lot of the local drinkers are energy workers in Alaska’s oil industry way up on the North Slope. They go up for two weeks at a time, work for 60 hours each week, and then fly back to their homes and take the next two weeks off, which they end up spending getting shit housed at the bars.

“Up here, we only care about four things,” he said.. “Eatin, drinkin, fightin, and fuckin!”

I came back from downtown the next night and noticed that the clouds had lifted off of the Chugach Mountains. I found my window. When it’s nice, I realized, now is as good of a time as any.

I got my gear together and left the hotel at 1:00am for a 104 mile ride northeast up the Glenn Highway. Hopefully I would get there by the next afternoon, camp at the Grandview Cafe, and come back to Anchorage the following day. 208 miles, two days. With cargo. The first one being mostly uphill and overnight. I had obviously learned nothing from my previous trip.

There was plenty of light outside to get me through the early morning. The glow of dusk was endless as I rode under the twilight in what felt like a morning that would never end. The midnight sun was just below the red horizon to the north and the mountains to the east carved dark green shapes into the sky.

After 30 miles, the road turned northward and passed through the Matanuska Valley. The sun would be up in an hour. Mist hovered above the ponds and marshes. Clouds hung above the mountains to the south. To the east, Lazy Mountain rose high above the town of Palmer, where I planned to stop and get breakfast.

Palmer was the last town on the highway that I knew of to get food before going into the mountains. After that, I could have found a roadhouse every 30 miles or so, but nothing I could rely on. I sat outside McDonalds for an hour and waited for them to open before realizing that a grocery store and Starbucks in the shopping center were open already. The lady at Starbucks told me that she goes with her family up the Glenn Highway every year and camps around Mile 85, a forested area near the pass with a number of lakes and back roads.

Just east of Palmer, Lazy Mountain stands 3500 feet above the valley. The Matanuska River comes out of the range and passes around it from the east. The highway goes alongside the river for the next sixty miles upstream until passing within eyeshot of the Matanuska Glacier. That was where I meant to go.

After passing through a heavily forested, uneventful part of the highway for 10 miles, I reached the river. Up ahead, the morning sun broke out of the clouds. I stopped at a lookout where the river braids across a gravel bar a half mile wide.

This river, like many in Alaska, is glacier-fed. Over time, glaciers move along their valleys, grinding the bedrock underneath into powder, which gets carried downstream by the melt. Whatever sediment isn’t carried out to sea ends up accumulating on the riverbed, causing the rivers to braid over large gravel bars. Backpackers often attempt to ford rivers like these by scouting out the smallest braids they can find. I’m nowhere near that ambitious. Not yet.

The valley narrowed and the highway followed closely by the river until it passed by King Mountain, a large solitary mountain that looked as if it stood out over these lands for many ages. I remembered seeing it online when I scoped out that highway on Google. Too bad I didn’t think to scope out the rest of the highway, or I would have been more prepared for what was coming.

To my disappointment, the highway parted ways with the river and climbed steeply along the facing ridge, gaining a lot of elevation at very little distance. So this road did have some grades, and they were ugly. Shit. I wasted no time getting started and hit the first climb for twenty straight minutes.

It turned along the slopes of the Talkeetna Mountains, giving me plenty of scares whenever I looked over the guard rails. I was inches away from one wrong move, which could send me tumbling over rock slides for hundreds of feet. I turned back and saw a great view of King Mountain rising high above the river and forest to the west.

Out ahead, the highway continued to climb, occasionally giving way to a downhill coast to a stream, and then winding even further upward. I did nothing but climb for the next hour, hoping that I would come around a turn and see the road level out, only to see it go further upward.

Somewhere in the middle of this, I passed a lady named Renee, who was on a tour from Anchorage to Los Angeles. It was her second day in. She spent the last night in Palmer, planned to get over the range, and continue towards Glennallen in the east. After talking I bit, I passed by, pushing hard into the next mountain grade. She had more cargo and was pacing slowly for the long term, and obviously intended on saving her strength. Instead of say, leaving in the middle of the night for two centuries back to back.

At this point, the top of the pass was five miles away. To my right, the mountain slopes curved down to the edge of a gorge, where at the bottom, the Matanuska was raging in the late morning sun. Lakes were everywhere along the slopes, drawing local people far and wide to come out in trucks, RVs, and fishing gear.

I finally made it to the top of the pass around noon, and the valley opened up ahead. To the south, the Matanuska Glacier reached far across the valley, carrying ice and rock from the high places of the Chugach range, where it turned upward for another twenty miles. Headwaters braided out from the glacier, forming the river, and carving into the ravine downstream.

Lion’s Head, a small, horn shaped mountain, stood on the north end of the valley. It was the remains of an ancient volcano that had been scraped away by glaciers long ago. After millions of years of friction, it was all that remained of a prehistoric mountain in the alpine country. And still, this place was as wild as ever.

The fatigue finally caught up with me at mile 100. I crested the high end of the pass, and hoped to get 9 miles of mostly downhill, where I would set up camp at the cafe, get some coffee and red meat, take a long nap in my tent, relax and enjoy the rest of the afternoon.. oh shit. I came around a turn and looked in horror as the road went downhill at a 7% grade for almost a mile to the bottom of a canyon, then crossed a bridge and went back up the other side at 8%.

You have got to be fucking kidding me. Already exhausted from riding all night, and with only four miles to the campground, shelter, and hot food, I had to haul my cargo up a fucking mile of hard uphill. Dammit.

Bitterly, I coasted down to Caribou Creek and started a long climb up the other side. A climb like this in the early morning is one thing, but I had already been on the road for twelve hours. I fought my way up the other side, inch by inch, swearing and taking breaks every few minutes. It made no difference.

The road finally leveled out, and I descended to the cafe where I got the best Philly Cheesesteak of my life.

The Grand View Cafe is on mile 109 of the highway, on the eastern slopes of the range. It has a restaurant, RV park, tent sites, families, dogs, campfires, and short hiking trails out to the river. When I got there, I set up my tent, locked my bike, ate a rewarding lunch, and took a nap until the late afternoon.

I got back out and saw Renee setting up camp at the site next to mine. She planned to keep going east to the town of Glennallen the next day, another 75 miles of mostly gradual descent from the range, then make her way out of the state and into Canada after that. For this trip, I would be turning the opposite way, riding 104 miles back to my hotel in Anchorage.

Next time I want to keep going east. The highway descends out of the mountains and levels gradually into a large plain of lakes, tundra, and spruce forests before reaching Glennallen, the Copper River, and the edge of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. From there, you can see the St. Elias Mountains, some of whom soar higher than 15,000 feet. The Copper River flows along the edge of the plain, and is famous for its salmon, who migrate upstream to their spawning grounds every summer by the millions. People and bears alike wait for them in the river, easily catching more than they can ever eat. I would love nothing more than to get out there, wait by the water, and eat one right out of the river like a fucking caveman.

A family in an RV saw me with my bike and gear, covered in a night’s worth of dirt and sweat, and wanted to know where I was headed. Then they offered me some of their campfire hot dogs and homemade wheat beer. I’m never one to turn away good road magic, and took them up on it.

Isolated rainclouds came in from the east and ran me back into my tent, where I slept like a rock.

My phone alarm went off early the next morning and I didn’t want to get up. I’m pretty hit or miss when it comes to camping. Either I’m asleep peacefully, or I’m tossing and turning, waking up every 45 minutes. Thanks to the workout I got the day before, and the light drizzle of rain on the tent ceiling, I had a calm, uninterrupted sleep all night.

I packed up, got a quick breakfast, and turned west on the Glenn Highway, dreading every second that I would have to climb the far end of the 7% grade at Caribou Creek. It was the same distance as the day before, just a notch lower in difficulty. Instead of climbing 8 feet, I would only climb 7 for every 100 in distance.

I descended down the facing grade, crossed the bridge, and got moving at a good pace as soon as it got to 7%. Ten minutes later, I got to the top, surprised at how much better I felt. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it was easy, but it was, I would say after a good night’s rest, doable. It turned towards a short descent, another steep climb, and then mostly downhill for a while.

Every awful climb I endured the day before was in my favor now, and my cargo weight made me go even faster. I was on the side away from the guard rails, my confidence was at an all-time high, and I had no problem shifting into high gears, flying down the grades, following the Matanuska for 60 awesome miles all the way out to Palmer.

I got there in the early afternoon, coasted down a big hill, and made the mistake of getting dinner at McDonalds. A man standing in line recognized me from the campground, reminding me of how small the world is in a big state like Alaska.

I was just about at sea level when I left Palmer, turning south at the junction towards Anchorage. It might as well have been uphill with the headwind I was getting. That, and to the traveling cyclist, a McDonalds combo is the equivalent of adding ten pounds of rocks to your cargo. The last 40 miles back were uneventful, and I had to deal with the added punishment of two centuries worth of riding and a full stomach’s worth of bricks to burn off over the next few hours.

I got to my hotel at 6:00 that evening and fell asleep without bothering to eat or take a shower.

I had two bike tours behind me now. Both of them kicked ass. Both of them were brutal. And both of them were unbelievably rewarding. Would my last ride on the Seward Highway be as challenging and frustrating as the other tours? Probably. Would it be an amazing adventure because of those reasons? Absolutely.