The Catacombs of Paris

The Catacombs of Paris

Far below its decadent creperies, cafes, famous landmarks, and bustling city centre is a huge network of underground tunnels that were once used to bury the remains of millions of Parisians. The Catacombs of Paris remain mostly closed to the public, but one section in the Montparnasse District near the city centre is open for tourism, drawing many curious visitors to see the hallways of the dead.

I visited Paris for the first time recently, and the Catacombs were almost at the top of my list (only to be outdone by the wonderfully iconic Notre Dame). I arrived an hour early and waited in line, which was already rapidly growing. When I reached the entrance, I got a handheld phone for the audio tour and descended a long spiral staircase to the opening passage. For now, only the stone walls of the abandoned mine lay ahead. I loaded the first track from the tour and started walking down the dimly lit hallway.

It talked about how the ancient quarry tunnels under the city became a burial site on a mass scale in the late 1700s, long before a more effective burial infrastructure was developed. There was a literal excavation of overflowing remains from cemeteries to the catacombs below – a project that took the city twelve years to complete. Generations of more than a thousand years of the city’s rich history adorned the hallways. Famous artists, revolutionaries, common folk. They all joined in the same fate along the dark walls of the tunnel.

I reached the first corridor of neatly stacked bones – a pattern likely used to store the dead as efficiently as they were able. It went on for what must have been half a mile. It was all without a doubt very macabre and disturbing, yet there was a beauty and art to their work that I think any visitor can appreciate.

And this was only one section of the Catacombs, whose tunnel system is estimated at 200 miles of underground passageways. It remains open from Tuesday to Sunday of each week. If you get the chance, bring headphones, load up your favorite Carcass album, and check it out.

For more information:

Green River Revival at USNWC Charlotte

Green River Revival at USNWC Charlotte

Every year on St. Patrick’s Day, the US National Whitewater Center hosts the Green River Revival, an outdoor festival centered around a huge artificial whitewater course in Charlotte. It draws thousands of people in green apparel, blankets, dogs, kids, and beer. Runners warm up for the Color Me Green 5K, kids ride across the park on the ziplines, people climb rock walls, and boaters of all skill levels paddle the green river.

I’ve only seen these rapids on Youtube, which isn’t saying much, but today I’m going to run them in full color. But first I want to get aerial footage of the river. I find the zipline tower, mount my camera on a helmet, and spend 90 minutes going back and forth on the ziplines over the park. At 1:00, they release the green powder, which bleeds its way down the channels. Crowds of people cheer, and boaters in all kinds of watercraft follow the green streaks of river dye down to the lower pond.

I walk around and scout the greenwater channels. In this park there are two: A fast Class III-IV channel to the right and a longer, slower II-III to the left. Beginners go left. Nonetheless I want to at least see what the harder one entails. It is an almost continuous rapid of big Class III waves for the first half before it passes in front of the welcome center and the restaurant. Near the end it drops into a huge, thrashing hydraulic with turbulent eddies along both sides. I see kayakers run it by skirting the eddy line on the left, hopefully missing the meat of it. In a big raft you would just punch through the apples. My little boat would surely get tossed around like a new fish.

I feel better scouting the left channel. It starts with manageable Class II waves for the first half, eventually speeding into a nearly continuous series of Class III wave-holes – and one notoriously big M-Wave in the middle. More on that in a second.

I suit up and paddle to the top, dropping over a small river-wide ledge and going straight for the first of several well-spaced play waves. I pass groups of kayakers along the eddies, who typically wait their turn to flip around in the current. The channel splits around an island, rejoins and starts picking up speed. Out ahead it constricts under a bridge, creating a fast pourover that rushes straight into a snake tongue and the big ass hydraulic that they call the M-Wave. A guide told me to run it on the left so I wouldn’t get smacked in the middle. I take his advice, clearing a small wave under the bridge and charging as hard as I can along the left side. I need the right amount of inertia and balance or I’m joining the swim team for the rest of this. I slam into the wall of foam, pulling a hard stroke right through the pile.

Holy shit, I cleared it! I’m flying down the channel, fighting to keep my boat straight. I barely have time to celebrate before I’m closing on another big swell. I clear that one with a clean lateral stroke. A hundred feet ahead is another hole that could toss me out, so I eddy out to the right, pass it, and continue down the middle. More laterals try to surprise me, but it feels like a straightforward path to the bottom. A big lateral wave at the very end sends me headfirst into the glassy, Jolly Rancher colored greenwater. I wash out and recover in the bottom pond.

I swear I have a love-hate relationship with this sport. These kinds of swiftwater rivers have created some of the most amazing, memorable trips I’ve ever had – yet I’m often equally as frustrated after capsizing and washing out. My excitement is just as real as my uncertainty, and I can never seem to get my head around it. How the power of water can create this dangerously amazing way of life. But this is what I do. #thisispackrafting

I sit at the restaurant as the day is starting to wind down. Boaters are still hitting that mean looking Class IV that I’m definitely not running today. I drink an IPA because the menu says it’s from a brewery in Charlottesville. I’m heading that way on a train later because I’ve never hiked Old Rag before and now is as good of a time as any. My life has had a lot of firsts as of late.

So yeah, greenwater rafting. Come out to USNWC Charlotte next St. Patrick’s Day to see it for yourself. I enjoyed it, though my only real serious complaint was that I didn’t see any green beer. Nonetheless it’s a fun river trip, and you can even bring leprechaun sunglasses if you’re feeling festive.

Backpacking the New River Gorge

Backpacking the New River Gorge

Everything feels lighter in the shoulder season – a time of year when the weight of the hazy summer gets blown away by cool air, the sky turns to a dark blue, and deciduous leaves turn gold in the late morning sun. I am the only passenger to step out of the train at Thurmond on Wednesday morning in mid-October. Canyon ridgelines are high and steep. The air is brisk, yet it will be at least a week before the forests turn to red. The New River is raging at a highwater swell. Waves are loud and chaotic. It’s moving fast. I cross the bridge and point my camera back to the town.

I am back to the New River Gorge on another adventure because two river trips aren’t enough. My trail route is scribbled on paper. I pack two days of food. I think I have enough layers. I reach the far parking lot and look for the Southside trailhead. As I walk north, it becomes evident that this was once a railroad track, now decommissioned and converted to a hiking trail. There is virtually no gain, and many rails and cross ties lay on the ground, collecting moss, rust, decay.

I hike east for two hours before the canyon bends northward. After a mile, I go down to the riverbank to look at Surprise Rapid, a bigwater mega-hole that threw me out once upon a river time. True to its name, it’s difficult to see at horizon level. But rest assured it’s there, waiting to give any novice boater a thrashing. I continue north and set up camp near the ruins of the Brooklyn Mines, one of several abandoned mining settlements that once belonged to a thriving coal industry – only to be left behind when the industry, and its people, moved on.

Later that night I see the moonlight on the side of my tent. I get out and walk to the river’s edge. Canyon walls and the rushing river illuminate in blue under a waxing gibbous moon. To the north I see Cassiopeia, one of many constellations in our hemisphere that I learned to recognize as a kid. I sleep uncomfortably. I packed one layer too light in effort to cut corners and now I’m regretting it. I’m not cold enough to be in danger, but enough to have to keep moving. The night seems to go on forever as I sleep intermittently, waking up to shift around and bring up my core temperature.

I get through it and pack up in the daylight. I hike north, passing Baloney Hole Rapid. The back story to its name has to do with Surprise Rapid upstream, where the Surprise Hole would toss you, your canoe, and everything in it in different directions – including your baloney sandwiches. And you would have to gather them up in the flatwater after. Baloney is a smaller rapid by local standards, but at today’s levels it still looks huge.

The trail meets Cunard Access Road and I hike up switchbacks as it climbs steeply along Coal Run. At times the elevation reveals dramatic backdrops of the far canyon rim through openings in the trees. I find the Kaymoor trailhead and continue north. On a terrain map I can see a shelf halfway up the gorge, where the Kaymoor appears to follow. Sheer sandstone bluffs of the Endless Wall line the far rim for almost three miles, and the roar of the Lower New River echoes from far below.

This canyon is old. Its origins date back to before the Ice Age, when a huge continental glacier blocked the river downstream, forcing it to change course and flow into what is now the Ohio River Valley. Yet the New River stayed on its present course, continuing to carve into millions of years of bedrock – even as the landscape around it shifted and folded into the mountains that we see today. I hike on the western side, wondering how many ages it took these walls of rock to compress and erode under pressure and time.

My hunger distracts me from the river’s epic backstory. I find a flat mossy outcropping to sit down and eat. Reception is spotty, but just good enough to receive a message from my boss. One of the website modules is down and our temp can’t figure it out. I try to load it up to investigate, but my phone battery dies in the cool temperature. Shit, I have to get out of here and find a signal. I am four miles from the Kaymoor Mine trailhead. I take off at a hard pace, regretting that I don’t have time to enjoy the view.

Well, almost. The canyon bends to the right and the western side of the New River Gorge Bridge slowly comes into view. I reach the Kaymoor Mine Trail and begin a steep uphill climb out of the canyon. Parts of it are steep trail dirt, wooden stairs, or stepping stones, switching back along an old connector from the west rim to the mine site at the bottom. I get out, sit on a rock, and take out my phone and charger. It’s what I thought it was. I uploaded a code revision two days ago and forgot to update a database table and it broke the query. I fix it, call my boss, and leave on the road for the campground.

Conveniently located next to the trail system, the Arrowhead Bike Farm is a self-proclaimed Biergarten, advertising “Bikes, Brats, Beer, and Camping”. And the other thing they don’t advertise but also have: dogs and goats. It is literally across the road from the Long Point trailhead, offering perhaps the best unobstructed view of the bridge. I leave my backpack at the main building and check it out.

When I get there, I discover that this overlook is an outcrop of high cliffs on three sides and a panorama of 300 degrees. I’m terrified as I timidly crawl along the middle to the vantage point. This is freaking me out, BUT! Holy shit, that bridge is huge! Out ahead I see a perfect end to end view of the New River Gorge Bridge, towering above the valley below. Tiny cars go silently from one end to the other. The river runs wildly along the canyon floor. It is ten times bigger than I remembered from my computer.

I expect my surprise is like that of the Rock Biter from the Neverending Story when he first came out of the woods and looked at the Ivory Tower. Regarded by its creatures as the “Heart of Fantasia”, it was an icon in their land. Likewise, I think that has happened here with this bridge. Matter of fact, Bridge Day Weekend begins tomorrow – and with it, base jumpers, one after another, plummet into the gorge. I, however, have other plans. I hike back to my campsite, unaware that everything is about to get derailed.

I try to sleep and the left side of my head is congested. Fuck. I know what this is. I’m at the onset of a bad headcold, one of about two I get each year. I’m supposed to be out here for three more days and raft the Gauley on Saturday, but I don’t see that happening in this state. I take out my phone, cancel the rafting trip, and reschedule my train from Sunday to tomorrow. It won’t be fun, but it will get me home two days sooner.

The night is cold and awful, but I get through it and pack up in the morning. Fog along the canyon rim frosted over the rain fly. My face is throbbing from sinus pressure. But I’m well enough to hike for one day, even if I do have to blow my nose on the grass. I head out on Gatewood at 9, going for a half day hike to the Thurmond depot.

Dogs bark at me from the houses as I walk along the back roads. I forgot that country dogs are like that. I used to get chased by dogs all the time on my bike, like the Rottweiler in central Illinois that ran after me for 50 yards. Most of the ones here are on a chain or behind a fence, but you never know.

At midday I actually do get approached by one. A small dog resembling a half-grown lab puppy comes up to me wagging his tail. It has been a shitty day, but it’s always good to have a dog come out of nowhere who wants to be my friend. I pet him and he starts walking with me on the road. Away from his house. I’d bring him along if I could, but I don’t feel like talking to the local police. I tell him to “Go on, git!” and he goes back home.

I reach Thurmond at 3pm and wait out four more hours, sick, hungry, exhausted. And without tower service. So I can’t check if the train is on time, which often times with Amtrak it’s not. If I miss it, I’m stranded out here for two more days. In the rain. Because yeah, that’s in the forecast. The canyon darkens, and I see the waxing moon again, carving sharply into the evening twilight sky. At 7 I hear a familiar train whistle and the headlights of #51 rumbling in from the south. I board, check in, and immediately go to the dining car for whiskey and a roast beef dinner. I’m almost too sick to enjoy it. But not quite.

Sixteen shitty hours later, I’m finally home. I get medicine at a CVS and sleep all afternoon, order Chinese takeout, and sleep into the next morning.

I don’t regret it. I got to have two good days on the gorge, and it looks like I am going back if I want to use my raincheck credit. I have $213 at Ace, if anybody wants to bomb the Lower Gauley next season.

Appalachia By Train And Raft

Appalachia By Train And Raft

The Amtrak Cardinal and Capitol Limited lines travel from Chicago to the east coast nearly every day, allowing access to a number of popular, runnable rivers. With a packraft, reaching them is an easy matter of packing up my river gear, riding on a train, and hiking out to a boat launch. On this tour, I combined three different Appalachian river trips into a week-long itinerary of train rides, paddling, and hiking.

Day 1: Packrafting the Potomac

I leave the train at midday and find the riverside trail going west. The river rapids of the Potomac echo through the trees. The afternoon sun is hot and my pack is heavy. I walk for two miles and reach a boat ramp owned by a local tubing outfitter. The guy tells me to stay away from river right. It has collected a lot of debris from flooding and one section of it is sieved out. The reality of this advice, and the collective roar of swiftwater a thousand feet downriver is making me nervous. I’m scared of it. But I can’t look away.

I’m back in Harpers Ferry for the fifth time, setting up to run my packraft on the Potomac River past the town to the 340 takeout downstream. It is a popular Class I-II section of intermittent ledge rapids, drawing a lot of open top kayaks, canoes, duckie boats, innertubes, and every so often some dude with his own green inflatable boat and GoPro that he rigged off of the stern.

I launch out and paddle to the left side, looking for a runnable line through the rocks. Little channels pour every different way and I’m forced to navigate on the spot. I recall seeing a straight current to the right in the satellite view. But since that section isn’t safe, I have to paddle through a boulder garden, often ferrying along ledges to find a way through. My camera keeps going out of position when I go over a wave, because there’s no way to fully tighten the ball joint on my tripod. So I keep having to fix the camera position, which is the most important thing about this trip, because I’m all in it for the Likes.

I paddle fun, bumpy rapids for a quarter mile, then pass the town and the confluence with the Shenandoah. The river widens. I hear another rapid ahead. Again, left is the way through. As I go east, the clouds behind block out the sun and the valley darkens. I need to hurry.

The river channels into Whitehorse Rapid, the only wave train of any notable size. Even so, you could run it in an innertube, fall out, and float harmlessly to the end. I skirt the right edge, ferry to the boat ramp, pack up, and scramble up to the 340 bridge. The hostel sits on a bluff on the other side. It’s my fifth time staying there.

I usually travel alone because I like to do everything on my own terms, but the more extroverted part of me likes to meet people when I do. Which is why I like hostels. They bring adventurous people together in an environment that allows travelers to connect with each other, while at the same time continue on with whatever their thing is. The one in Harpers Ferry is particularly interesting because it hosts a lot AT thru-hikers, cyclists on the C&O, people on roadtrips, and guys like me coming out and doing random shit.

This time I meet a group of 25 people from DC on a cycling meetup. They rode out here on the trails, plan to hike Maryland Heights and go tubing tomorrow, then ride back the day after. When I meet them, I realize this is a demographic of people here that I had never considered: weekend warriors from DC.

I have beers and shots with them as we trade travel stories and river trips. One girl is bringing her kayak to Gauley Fest in two weeks. Another one has questions about Iceland. And another one is a government security employee who wants to get out of it and travel more. So do I. If it were up to me, I would be nomadic and stateless – traveling, taking pictures, making videos, writing stories. But vacations will have to do for now. I finish one more beer with them at a bonfire and go inside to my dorm.

Day 2: Capitol City Layover

I hike back to the town and board the eastbound train in the late morning. Even with my ultralight gear – packraft included – I feel like my pack is weighing me down. I have to get rid of this thing if I’m going to find a brewery. When I get to DC, I check it in with the agent and go outside. Without it, I can walk around instead of hike, if that makes sense.

I load up Google Maps and put in “Brewery”. Twenty minutes later, I’m at Capitol Ale House sitting in front of a colorful flight. Vanessa is texting me something funny. We talk a lot, even though she is in Sweden and I’m in the states. I met her on a trip last year and we have been talking about Sigur Ros over WhatsApp ever since. I send her a link to a B-side from Julianna Barwick, whose angelic voice can melt a heart of stone.

I leave Union Station on the Crescent train for my hometown.

Day 3: The Shenandoah by Packraft

I drive north and park my parents’ van at the Inskeep launch three hours later than I meant to. It takes me 45 minutes to set up the raft and sort my gear. I get moving on the river at 10, losing most of the good hours of the morning. The Shenandoah is mostly calm, opaque and brown from rainstorms washing dirt from the mountain streams. It’s low but has one or two good feet above most of the ledges, often enough for me to get through without looking for a line.

Halfway through the day, I start passing large groups of tubers and kayakers. Why didn’t I think of this in college? I lived in Harrisonburg for years and it never occurred to me that a crew of us could float this river. Complete with outfitters and coolers of beer, we could have been 20 strong. But the truth is, there is a lot of natural beauty in the Blue Ridge Mountains and West Virginia that I took for granted back then. Hell, the AT is 12 miles away from the farm. But that’s why I keep coming back now. I’m making up for lost time.

The day gets hot and I’m running out of energy. It’s my own fault I didn’t start earlier. I have to get focused, because I need to scout the Compton Rapid, considered locally as the boogie rapid of the river. I climb through bramble to get to the riverside and take a look. I can see the line clear as day. You start it on center right to miss a ledge hole on the left, and then work your way left to avoid another one on the bottom right. I easily run it to the bottom.

I take out at Mile 19 and dry my gear in the sun. It’s late in the day and I’m exhausted. I hike the Indian Grave Trail a few miles up the ridgeside and find a flat area to set up camp.

Day 4: The Most Convenient Shuttle Ever

I pack up and keep going up the ridge. To my right I discover a spring and refill my bottles. The trail steepens as the 9am sun shines between the trees, already hot in the morning haze. In its steepest part, this trail is like a staircase of rocks cutting into the mountainside. The sun beats on my face and arms. I see the Shenandoah meandering below the humid backdrop of the Blue Ridge.

I reach the ridgeline of Massanutten Mountain and turn south. On a map you can see it circle around Fort Valley to the west, a small, solitary valley a few miles wide. One road goes through it from 675 to the valley’s end, 20 miles north. Even after all these years it’s the first time I’ve actually seen it.

I go south as the sun rises to an unforgiving angle. There are a lot of exposed rocky areas on the trail that offer little shade. When I do find it, I often stop to catch my breath and bring down my core temperature. I’m supposed to hike 11 miles to the trailhead, but with three full bottles and nowhere to refill on the ridge, I’m starting to have serious doubts if I can ration enough water for this.

What I do know is that Habron Gap is 4 miles from Indian Grave where I started. If it gets too hot, I’ll hike back to the road from there. I spend two hours fighting my way over ridgetops, and eventually get on a steady decline to the gap.

When I reach it, I have to decide. I can ration what I have left for seven more miles to 675, or I can hike down the ridge from here. I realize that even if I do have enough water, I would still be miserable in this heat. I take out my phone and look at the terrain map. Shenandoah River Outfitters is three miles down the mountain. I have to get from the blue dot to the red pin.

I finish my second bottle and start down the Habron Gap Trail. It’s smoother than Indian Grave, with less bramble growing along the sides. It goes steeply down the high ridge for a mile before leveling out in the trees. There, it flattens and I pick up my speed. It’s good to be in woods again.

Fifty yards to my right I hear the rush of a mountain creek. I go over, drink my last bottle, fill up all three, drop tablets into each, and keep going.

Finally, I make it to the road. I hike one last shitty mile to the outfitter and ask the lady where I can refill my water. She says there is a hose around the side of the building.

“Okay. What would you charge to shuttle me back to the Inskeep launch?”

“$30.” DONE. Twenty minutes and two Powerade bottles later, I’m loading up the van and driving out.

Several years ago, I stopped at the Thunderbird Café after another river trip, solely because of the name. I go there again, feeling like this might become a tradition. When I sit at the counter, I drink an extra glass of water. Just because I can.

Day 5: Hometown

The Shenandoah Valley is home. And it doesn’t matter how much time I spend away from it or how much I change, it will always be home. Though I’m too restless to ever move back here, I generally feel like I need to come back about once or twice a year to the quiet town – for the familiar hills, the fireflies, the sunrise on the Blue Ridge, and the sunset over Betsy Bell. Even the Walmart is part of my old life.

I borrow the van and visit my college friend Pete for coffee. We meet up nearly every time I come back. He and Jill had just recently lost their dog of many years and adopted a new puppy in her stead. As somebody who grew up around dogs for half of my life, I get all too well the grief of their loss, and how the joy of a new puppy can heal a family of that sadness.

Pete leaves for work I drive to Gloria’s Pupusaria, because there is no such thing as too much corn masa. Later, my dad drops me off at the Staunton depot, where I once again leave my childhood home for a westbound adventure.

Day 6: Packrafting the Greenbrier

The river is six miles away. I plan to head out of White Sulphur Springs at 4am, determined not to make the same mistakes as before. But first, I eat a fruit breakfast my AirBnB host had prepared for me, and cut slices of the best artisanal cheese bread in the universe.

I hike out on the street in the dark, passing by the entrance to the Greenbrier, a huge world-class resort on the western edge of town, complete with a golf course, casino, spa, lavish weddings, expensive rooms, obscenely rich people, and the one thing I actually am interested in seeing: A decommissioned fallout bunker. The Greenbrier offers tours to their guests and the public to view the resort’s Cold War era fallout shelter, built to protect over 1,100 government officials from a nuclear disaster.

Maybe next time. I would need an extra day and I’m on a schedule. I walk by a parking lot and sit on a rock wall to rest. A security guard is just finishing his graveyard shift and offers me a ride. I load my backpack in his truck and get in the cab. He drops me off close to the interstate exit, a mile from the Caldwell boat ramp. I’ll take it. I get there and start setting up my raft at daybreak, which is the point. But first, I eat the artisanal cheese bread for breakfast. It is everything you ever want bread to be and more.

A canopy of fog hangs over the Greenbrier River and small patches of mist linger above the glassy flatwater. I push out and float into a smooth current. For six miles, I paddle through easy, bumpy Class I sections and the morning brightens. This is a scenic “family float” section of the river from what I can tell. I, however, do not waste my time floating anything, but make a hard pace in the cool morning.

The mid-morning sun breaks through fog and I pass the bridge at Ronconverte. A young fawn stares at me curiously from the river’s edge, perhaps the only eventful thing that happens before the valley narrows into a canyon. We stare at each other as I float by, careful not to spook it off.

The river bends sharply several times below the canyon’s cliffsides, passing from rapids to deep, clear flatwater pools. I think about why I do these kinds of trips. How the energy of a river really does accentuate the beauty of a landscape. When it’s calm, it brings out the peacefulness of the countryside in a way that never quite happens on foot. And when it’s fast and wild, its beauty is amplified through its crashing water and echoing roar across the valley. I never feel truly alive like I do when I’m fighting my way through a wild river rapid to its peaceful end. Because ultimately, the river does what it wants. And I have to enjoy the river on its own terms.

I get out at Fort Spring to eat. I’m two miles from the campground, and two rocky rapids as it turns out. I go around two bends and hear a loud roar ahead. Most of these rapids are small enough for me to eyeball a line, but this one doesn’t have a clear channel from the top. The main channel in the middle goes right into a rock at the bottom. Dammit, I have to get out.

I scout from the left. Sure enough, the center line would be fine if that rock wasn’t waiting to smack into my boat. The far left line right in front of me looks more promising. It’s tight, but I can get it with a quick right turn. I get back in and run through it as planned, but not without scraping the bottom. Good thing my packraft is made for that kind of abuse. I’ve hit rocks with it so many times and have yet to rip a single hole anywhere.

I get to another rapid and try to scout from the top. The current is too fast and I have to improvise. I go for the biggest channel I can find and get stuck on top of a rock just under the current.

Shit! Water is rushing around me on both sides. I lean out and put my paddle in the current, well aware that I don’t want to fall out and chase my raft down this bony ass rapid. Soon I’m freed and go out on the current backwards. I spin around and charge out on the tailwaves, staying clear of more rocks on the right.

This had better be it. Without a doubt, rapids like those are easier at high volume, even if it means bigger waves and higher whitewater grade. But today the river level is rated “Lower Runnable”, requiring more technical lines around the rocks.

I shore in at the campground and set up close to the river. When I go to the office to check in my site, I hear the meow of a kitten from behind the front desk. The lady tells me that it hitched a ride with her to work today. Apparently, the cat climbed through the engine of her car and sat just under the hood that morning. She got in the car and drove to the campground, and when she got out, she heard it meowing from under the hood. When she opened the hood to look, there it was. Not a scratch. Somebody has a guardian angel.

That night, a thunderstorm passes over the valley. I barely notice as the downpour bombards the rainfly on my tent.

Day 7: Take Me Home

The depot in Alderson is five miles away. The river, according to the campground website, has more rapids like the ones from yesterday. I’m reluctant to paddle any further. The last thing I want is to fall out in some bony rapid and hit my leg on a rock. Instead, I pack up and hike on the road.

Stuarts Smokehouse is well known on the river, very largely because they have signs that say things like “Pulled Pork & Brisket at Stuarts, 5 Miles!” I make a strategic three mile hike to get there at 11 when they open for beers and a brisket dinner. Outside, the sign reads “Cold food, warm beer, ugly women.” Sold!

I reach Alderson and wait out the afternoon at the train depot. Several boring hours later, I board the train one last time with my river gear in my backpack.

Later, the golden sun lights the fog gathering at the top of the New River Gorge as #51 passes under the high bridge and out of the canyon. It has a trail system and river of its own – also accessible by the Amtrak Cardinal.

The Prismatica Timelapse

The Prismatica Timelapse

Earlier this spring I created a timelapse video of the interactive Prismatica installation at Navy Pier, Chicago. Design and installation was by Raw Design and Quartier Des Spectacles. If you wish to find out more about their work, you can visit their websites:

rawdesign.ca

quartierdesspectacles.com

This installation is no longer on display in Chicago, but might appear again in another city. When I last checked, they said that the next location is TBD. I hope I see it again somewhere, this project was a lot of fun.

Part 6: Sigur Ros at the Harpa Concert Hall

Part 6: Sigur Ros at the Harpa Concert Hall

…continued from Part 5: Iceland in Full Circle

I can’t believe I’m doing this, I thought, as I sat at my computer last September with another flight reservation to Iceland loaded in one browser tab. A hostel reservation was loaded in another. And in the third, a ticket to Sigur Rós at the Harpa venue in downtown Reykjavik on December 30. I had entered my credit card in all three browsers. Everything was set. All I had to do was pull the trigger.

I was hesitating. I shouldn’t be doing this. I need to save my money. I was just there. And I’m going back already? I stared at the screen for a minute, conflicted. Then all at once, I thought “No”, and closed out the browser – and with it, my next adventure abroad. It was frugal, and wise. I did the right thing. I didn’t regret my decision.

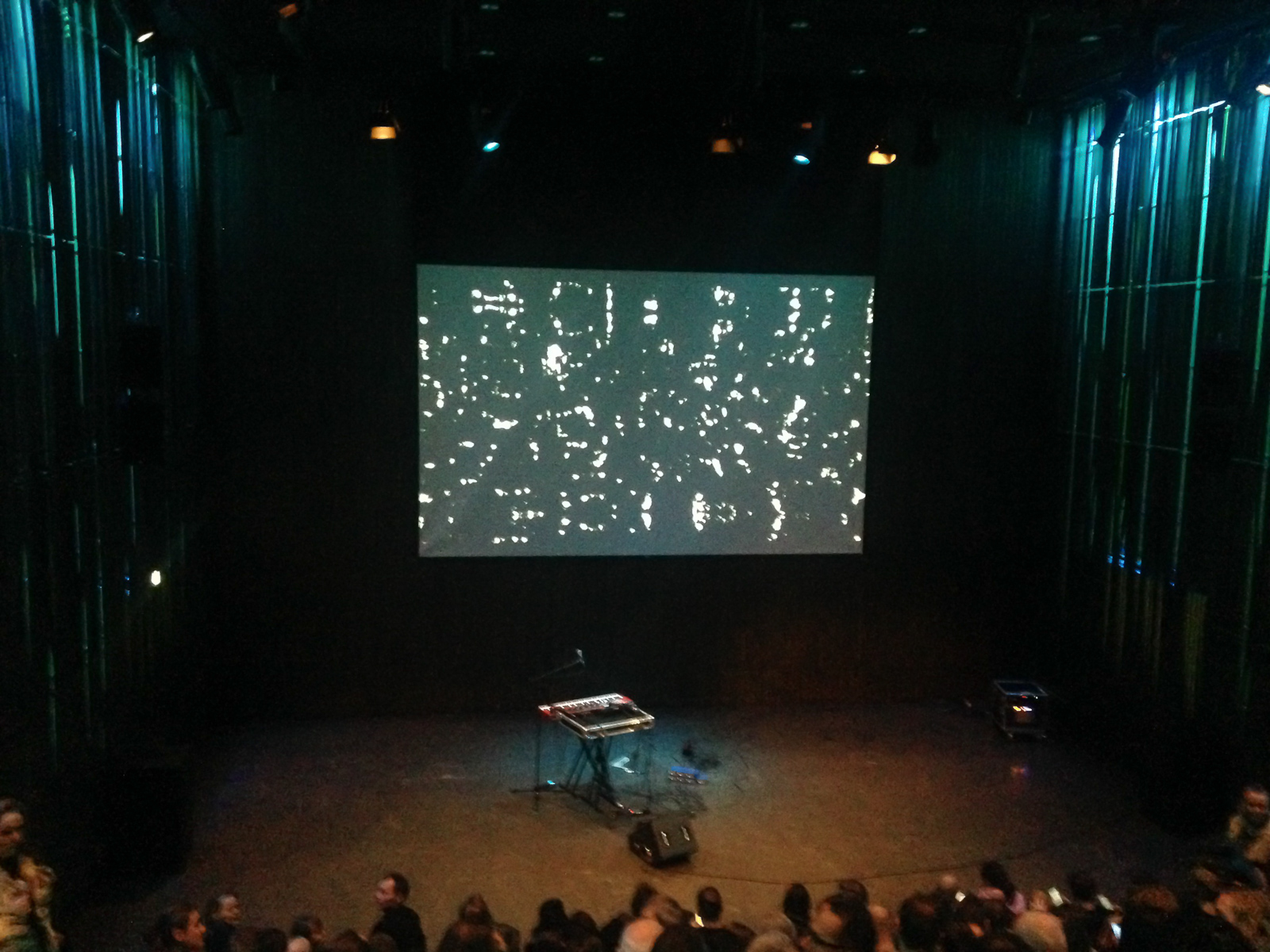

Sigur Rós had toured the world for most of that year, playing in big cities across Asia, South America, Europe, the states, and finally their hometown of Reykjavik, Iceland. They organized a four-day festival, Norður og Niður at the immaculate Harpa Concert Hall in downtown, headlining in the main Eldborg Hall for four sold out shows. It was a celebration of ambient music, art, theatre, and darkness: Northward and Downward.

The venue is geometrically flawless, I think, as I walk through the door. It is a prism of steel and glass, with thousands of complex shapes pieced together with precision – like something an architect drafted with a deliberately complex algorithm. I want to fly a drone in the main hall. I wait on the second floor with my day ticket to watch Julianna Barwick perform in a small theatre. Others gather around the entrance as we wait for the doors to open. She cancelled a tour in America one year to tour with Sigur Rós, and now many of their fans are also hers. I’m not at all surprised at her following.

I find a seat near the top and she comes out to the applause of 200 people. Stage lights dim to soft tones of blue as she takes the audience across a vast soundscape of ethereal bliss. Each song begins with a simple melody or texture, and by looping each harmony over the last, she transforms each sequence into a booming choir. Her music builds and fades with the grace of the aurora; I listen and feel like I’m floating across an interstellar plain between astral systems. It goes as far as my imagination can take it. Then all at once she ends as quickly as she began. I’m back on the ground. We applaud.

I leave and see a crowd of people pour out of Eldborg for the third of four Sigur Rós concerts that week. Tomorrow can’t come soon enough.

I spend the next day exploring the city and go back to the venue two hours early because I can’t wait any fucking longer to see this band. While I wait outside the door, Julianna Barwick sets up to play on an open side stage, because why the fuck not?? I’m convinced that the festival is just trolling me now. I get another glass of wine and watch her play even more of her graceful, ambient compositions.

Finally, I go into Eldborg and find my seat. The band walks onto the stage to a packed house of cheering people. They begin.

The stage darkens, and lights surround Jónsi like fireflies as he begins a simple note over a light backdrop of ambience. The three members literally play in the middle of their own light show. I quickly realize as I watch them that the light show is becoming a masterpiece of its own – changing in tones and moods with each nuance in their music. Somebody had a lot of fun building this.

For two hours, they play music from twenty years of songwriting, many times bringing me back to moments in my own life when their songs were with me. I think as far back as the early 2000s – a time when I was confused and uncertain about my future. I didn’t have the foresight or self-assuredness at the time to know that I would turn out okay.

The lights change colors to the piano intro to Sigur 1 from their Untitled album. I’m reminded of a girl who I met in my young years as a bass player. She liked my band and I liked her. We’re still friends.

The haunting intro to their signature track Glósóli captures the audience to the beat of a steady drum. I think back to the video; how its story connects with our adventurous inner child. In front of a panorama of Icelandic mountains, a brave group of kids are found climbing over lava rocks, jumping off of cliffs, flying over oceans. Likewise, Jónsi’s falsetto is soaring over the noise.

They fade into the familiar, hopeful resonance of Festival, my favorite track from Med sud I eyrum vid spilum endalaust. This album came out in 2008 right before I left to start a new life in Chicago. I remember wanting to put all of my baggage and pain from my life in Virginia behind – to hit a reset button and build a new life for myself.

The Air and Water Show happened soon after I moved to the city. I contacted a young Couchsurfer from Stockholm and we met to watch the air show at the North Avenue Beach. The bassline and guitar melody carry the second half of the song, and I think about when I sat with her on the sand – watching jet planes soar over Lake Michigan, over the skyline, between the buildings, across the city. We were each on an adventure. She was backpacking around the country and my journey then was inward. I never saw her again. But I never forgot that day.

By the end of the second hour, they have played many great songs from a twenty year span of memories. They close with the climactic Popplagið. One final story comes into focus as they drive through the chords and flashing light.

Last September I decided not to go to this concert. I sat at my computer, one click away from buying tickets to this very show. Ultimately, I got cold feet and backed out. Because it was too soon, too expensive, too whatever. I closed the ticket reservation and went about my day with little regret. When I came back the next day and loaded up their music, I was instantly overwhelmed with sadness.

I thought about my last night in Iceland in August, when a local asked me what made me want to visit her country. I told her that I was a fan of Sigur Rós of many years, and their videos from the mid-2000s made me curious about the Icelandic countryside. How their documentary Heima chronicled a series of unannounced shows they did around their country after a world tour. And how they ended at a park in Reykjavik in front of a huge audience. Ever since I saw that, it was my dream to see them play for their hometown crowd.

I suddenly knew that this was probably the only chance I would ever have to see this dream become realized. If I didn’t do this – if I didn’t buy these tickets – then I would never get the chance to again. Nor would I ever feel the same way about their music. For the rest of my life, I would have to live with an incredibly heartbreaking mistake – one that I might still have time to save if I stop fucking around and buy those concert tickets right now!

Frantically, I loaded up the itinerary that I closed out yesterday, well aware that any one thing I needed might already be sold out.

But everything was still there. The tickets, the concert, the closure, and the memories to come.

I took a breath. I pulled the trigger.

Now, they escalate into one last crescendo amidst the chaotic precision of their light show, masterfully projecting a wall of noise amidst the cheers of hometown friends and fans worldwide. They ring out to feedback. They put their gear aside. They take a bow.

And then it’s finished. And I don’t regret my decision.

But the celebration isn’t over yet. On the next night, I walk up the main street toward Hallgrímskirkja with Val, Jorge, and Zuzka to celebrate New Years Eve. The city has come alive with an incredible country-wide fireworks show. We near the top of the hill as they celebrate the holiday with huge bonfires and rockets exploding all over the city. For hours. All while the bells of the old church ring in the New Year. Having just been here in August, I was on the fence about coming back to Iceland so soon. But I know after everything that I made the right choice. I think every great place deserves a second visit. And possibly more.

Takk og gleðilegt nýtt ár, Ísland!

“Og hér ert þú, Glósóli (And here you are, Glowing Sun)…” – Jónsi Birgisson

Part 5: Iceland in Full Circle

Part 5: Iceland in Full Circle

…continued from Part 4: The Golden Circle

It was two days after Christmas. I sat on an overnight flight anticipating another Icelandic adventure, this time in the darkness of the Nordic winter. I didn’t know it yet, but in the next five days my trip would unravel into an insane emotional whirlwind of amazing places. I was coming back to Iceland, already, in this dark hour – this time to explore, eat local food, go to museums, celebrate the New Year, and perhaps most importantly, revisit a country that I had quickly learned to enjoy the first time.

The Blue Lagoon

At the time the average high in Chicago was in the single digits, and in Iceland it was twenty degrees higher with mostly clear skies. As far as the climate was concerned, I was getting a break. The trip there, not so much, though I had already planned a reward for the shitty overnight flight. When I got to Keflavik that morning, I got on a shuttle bus for the Blue Lagoon. I relaxed as the light of daybreak illuminated the lake and surrounding hills in ambient blue. I put on a mud mask and got a can of Gull from the island bar. The stress of my 6hr flight evaporated as I drank and swam about the lake among other travelers, watching gales of cold morning air blow fog across the hot water. When in Iceland, so they say.

The shuttle bus left for the city, and the sunrise took forever. Being only a few days after the Winter Solstice, it would slowly arc above the horizon in the south for a few hours each day before leaving us in darkness again. I tried to stay awake as the shuttle passed a huge snow-dusted lava field, glowing in the softest pastel blue I had ever seen. I was back. I couldn’t believe it.

The Northern Lights

I arrived in the city and slept my jetlag off in a hostel dorm. It took me 3 hours to feel like a functional person again. At 7:00 a shuttle from Reykjavik Excursions picked me up for a Northern Lights tour outside of the city. They brought us to Þingvellir National Park, an area with good mountain vistas an hour away from town. We drove through the dark country, passing many snowcapped mountains and farmlands, lit up by a waxing gibbous moon. Though the weather forecast was clear, the solar forecast on my aurora app called for 2%, a low percentage on the front of solar storms.

It didn’t matter. The guide pointed out a thin band of aurora over the north mountains close to the park entrance. To the untrained eye, it looked like a breath of cloud. Only in a few moments could I make out the green tones, dancing like a ribbon over the mountains. We got out. The air was in the low twenties with biting wind. But I got my damn Northern Lights, finally, after all this trouble. There they were, looking back at me as indifferently as an iconic mountain like Denali would – appearing, or not, when she feels like it. But this light show could vanish any second. I had to fucking do this.

I took off for the edge of the lot with my gear, frantically set up my tripod, took out my camera, lost the lens cover, focused on the shuttle headlights behind me, pointed back at the mountains, set to manual, plugged in the remote shutter, and started shooting. After a few underexposed shots, I found a good setting at f/2.8 ISO200 13s. Holy shit! There it is!! I was amazed at how much more color my camera was able to get from a 13 second exposure. To the naked eye, I only saw a fraction of it by comparison. But the picture was interesting enough that a few people started watching the preview screen as I stood there taking pictures. Here are a couple of my successes.

We lucked out. We were there for an hour, watching the aurora dance above the ridgelines. After a while, I was too cold to stay out any longer. The wind was picking up, and I felt like I had seen enough. I packed up and waited in the shuttle.

The Museums of Reykjavik

I didn’t have much time or budget to explore the city last summer, so this time I came back with more of both. I Googled something like “the best museums in Reykjavik” and it returned a great list of places to go – only half of which I ended up seeing. But first, I needed to eat. I left for downtown in the morning, hungry for a good, authentic, local Icelandic breakfast. According to the guy at the cafeteria, the sheep’s head, or Svid, was an Icelandic Viking tradition of thousands of years.

The cheek had the most meat, and was quite tender and flavorful. The tongue tasted about the same, and had a rubbery texture. But my favorite part was the eye. It tasted like cooked fatty tissue with a juicy middle, full of protein and flavor. It didn’t look appealing, but taste buds don’t discriminate.

Satisfied for now, I walked up to the Hallgrímskirkja Church to see the city at sunrise.

In other news, they have a Dick Museum in Iceland.

Just down the street from the cathedral, the Iceland Phallological Museum celebrates all dicks great and small. Whether you’re somebody to prefer a specific type of shaft, or perhaps you just want to see all the dicks, I believe there is a penis here for you. Take for example the taxidermied elephant dick hanging in the back room (pictured above). Feel free to take dick pics and buy your partner a souvenir.

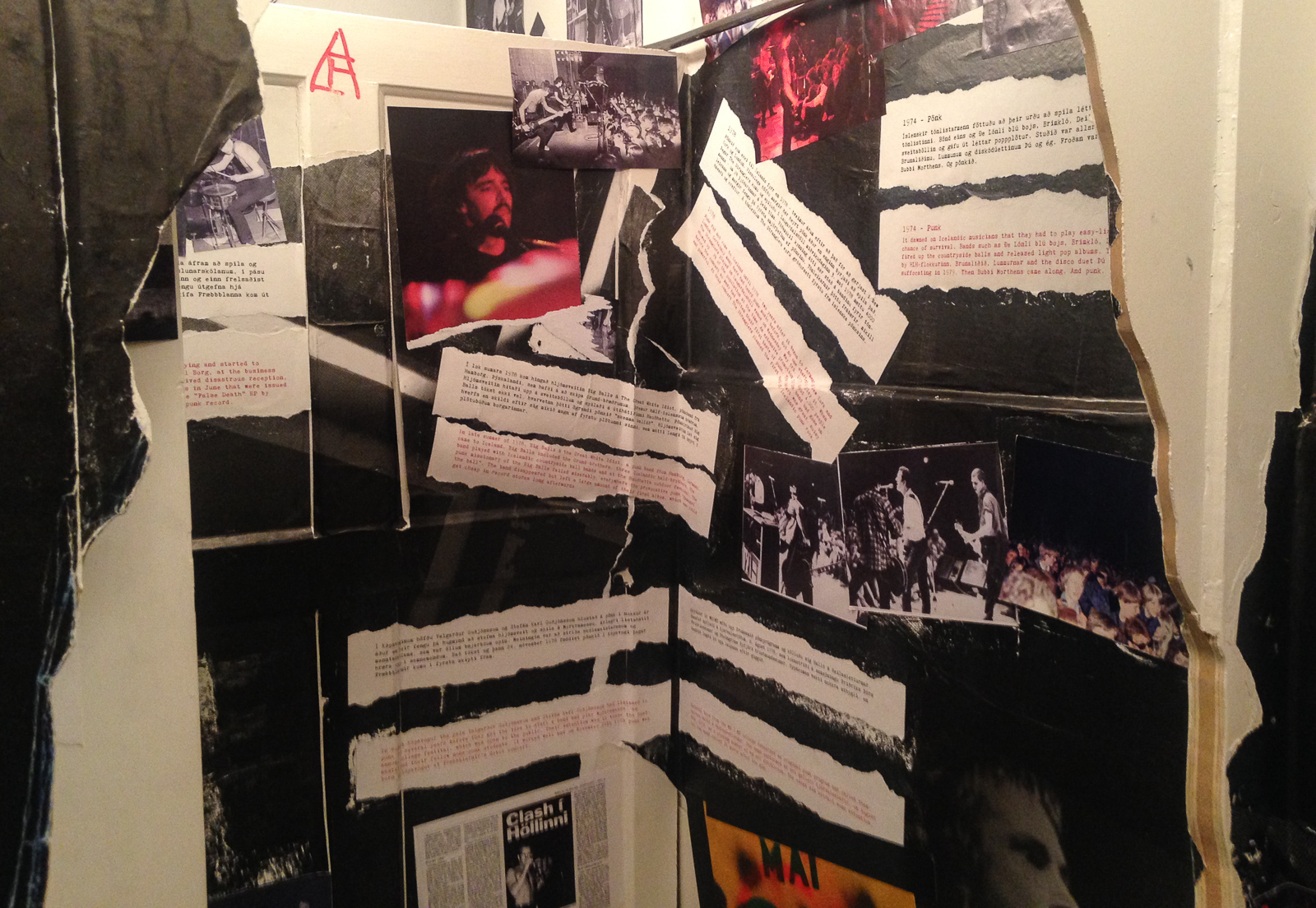

Informative, like the Icelandic Punk Museum, a tiny exhibit close to the Harpa venue nearby. This was a rad little hole in the ground showcasing the rise of Icelandic Punk Rock.

I went to the Whale Museum early the next day. It offers a self-guided audio tour with an mp3 player and headphones, where an Icelandic fellow explains many interesting facts about these great sea creatures. Rumor has it that in ideal weather conditions they can be seen flying above the city.

The South Coast

The city was great, but I needed to see the countryside. I drove around Iceland for a week last summer, and remember being impressed with the south coast. I came to find out later that I missed most of the important places in that area due to time. On this trip, I signed up for a south coast tour on New Years Eve to see everything that I had missed. The shuttle picked me up at 7am and we left at 8 from the BSI terminal an hour before dawn.

In the summer you can hike behind the Seljalandsfoss waterfall and see the landscape in front of it. Now, however, you would slide underneath the water. I enjoyed that as well as the iconic Skogafoss, another beauty created by the steep, cascading rivers of the high country. After a 40 minute visit there, we continued east and went on a short hike to the Sólheimajökull Glacier. It was an easy hike over moraine to the glacier and frozen lake below.

We reached the tiny oceanside town of Vik in the afternoon. I had dinner at the cafeteria and went out to the beach to take in the ragged shoreline. We made one last stop at Reynisfjara just in time for the 3:30 sunset. The sun slowly appeared beneath the clouds, casting red light onto the beach. Highland volcanoes lit up in alpenglow above us. Waves crashed on the black sand beach as the spires of Reynisdrangar darkened against a backdrop of pale blue.

The line of overcast met with the sea. There, the sun appeared, lighting the clouds ablaze in tones of red and orange. As we drove west, I made friends with Val, a teacher from Sao Paulo who was visiting Iceland for a few days. To her, that sunset was the best one of her life. I watched it slowly change the colors of the landscape and agreed, thinking it was certainly in my top five. It just so happened that a full moon rose above the white mountains to the north.

As the night darkened we passed farms and little towns, often seeing huge bonfires and fireworks from locals already celebrating the New Year. We reached outskirts of Reykjavik, where even more fireworks exploded above the city lights. The magic of their holiday was unmistakable – yet I couldn’t deny in that early hour that they were holding back. It was New Years Eve in Reykjavik, and the city was coming alive in celebration.

This story concludes at the Sigur Ros concert at the Harpa Concert Hall.

Part 4: The Golden Circle

Part 4: The Golden Circle

…continued from Part 3: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

“Every day, I go outside and look at the vast horizons. Just because I can.” -Mark Watney

Day 7: The South Coast

I had planned to drive up to the Hvita River, a popular Class II-III bigwater river just downstream from Gullfoss, to run in my packraft for a few hours. But my washout in the Heida River yesterday gave me doubts about shit like this. Not only is it scary to capsize in a big rapid where you don’t know the hazards, but it’s also possible to lose your raft or your paddle if you don’t get them right away. So I decided to hold off on packrafting for now, and perhaps consider it again with a few river buddies and proper rescue training. It just meant that I had to find something else to do. In Iceland.

I drove west and stopped at the trailhead to Svartifoss, which was an easy scuffle up the mountain through a lot of brush. There aren’t many trees at all in Iceland, but small ones do exist in patches along various mountainsides. I got to the falls an hour later and felt underwhelmed. Which was fine for such an effortless hike.

Another trail went northeast from the headquarters to the end of Skaftafellsjökull Glacier, which was a bit more interesting. This is one of many large glaciers of Vatnajökull National Park, an area of huge volcanoes and the largest snowfield in the country.

I hiked back to the van and drove west along even more gorgeous coastline. I passed many farms and ragged mountains, dwarfed by the highlands of the inland snowfields. The coastal village of Vik wedged itself between sharp mountains along the ragged shore. Backpackers were out trying to hitchhike. Two cute girls waved and smiled, trying to get my attention. Sorry ladies, but the van is full.

After a while, the mountains faded in the east. I stopped at a campground in Fludir, a little town with its own Secret Lagoon. Almost every one of these towns has something like this. Whether it be a hot spring, cave, hiking trail, or whatever, to explore. I could live in Iceland for months and still not feel like I saw everything. The sun was out in the late day, so I made the most of it and dried out my river gear.

I slept that night under a blanket of overcast. It was my last night on the road. And I never did get my Northern Lights.

Day 8: GULLFOSS!!!!!

There are waterfalls all over Iceland. In every river, every stream, everywhere. But only a few of them can measure up to the thundering Gullfoss in sheer magnitude and strength. At an average rate of 4,900 cubic feet per second, this monstrosity is a true wonder of the world.

I was lucky to get there a couple hours before the tourist shuttles arrived. I walked along the paths on the bank and pondered the bigger meaning of things to the deafening roar of ten million gallons of water. Here, the falls seemed immeasurable – full of beauty, incomprehensible strength, recirculating terror. Only the Canadian side of Niagara could rival this masterpiece, but even the falls there don’t share the same magic as these – where fire and ice have built upon and cut away from the land for many ages. This, my friends, was the mighty Gullfoss. This was the apex of my trip around the Ring Road.

I drove uneventfully back to Reykjavik and dropped the van off that afternoon. I don’t regret using it, but I hated the stress of being responsible for an expensive vehicle in another country. I was glad to be rid of it, and took a shuttle bus back to my hostel. The first thing I did when I got back was get some decent food.

The restaurants in Iceland often cost 2 to 4 times as much as they do in Chicago. Which was why I brought freeze dried food from home to eat during my roadtrip. Because of that, I saved hundreds. But a good exception is the hotdog stands in Reykjavik, which cost about $4 each for an Icelandic Hotdog. They don’t look like much, but they’re good and the price is right.

I was done running around for now. But I did have an interesting match on Tinder who wanted to meet up tomorrow. She was local, and in most of her pictures she was doing something outside on a bicycle or surfboard, which is always a good sign.

Day 9: The Cuisine of Reykjavik

The weather was back to normal: windy and wet. It got like that all at once yesterday right after I got rid of the van, which is awesome. Until today, I avoided the local cuisine because of the prices. But it was my last full day in Iceland, and I had money to burn.

My friend Sara told me about puffin meat, which she got at the Public House. I didn’t see it on the menu there and went to Íslenski Barinn instead. They served a few pieces of it in a jar with pickled onions, blueberries, lettuce. It had the consistency of liver and the savory taste of beef. It was good and worth trying out of curiosity, but I needed to fill up. I also got a lobster hotdog. It had chunks of deep fried lobster, cheese, some kind of sweet sauce, on a ciabatta roll. It was a home run out of the park. To quote from their menu, “True friends stab you in the front.”

I wanted to meet the Tinder lady, Iris, at the Lebowski bar that night. When I invited her, she said, and I quote, “It’s a shit place!” So I didn’t go there with her, but that didn’t stop me from going on my own.

We met instead at Mikkeller & Friends, a dimly lit, local, mostly quiet bar with a lot of good Belgian drafts. I’ll take it. She grew up in Iceland, spent a few years studying in the UK, and recently came back to her home country. It makes sense. To the adventurer, Iceland can be your own personal wonderland.

She had traveled all over the world on outdoor trips, including two months of field work in Ellesmere Island. Now that got my attention. She said at one point that her team was approached by a polar bear and they had to scare it off with flare guns. They were about to use a real gun on it before it finally left them alone. It sounded like an episode out of Planet Earth.

We went to another local bar and then another (as local as they get in the tourist season) and I had a good sample of some local Icelandic stouts. To me, a good stout is always better when the weather is shitty. We made one last stop at an upscale bar on the waterfront where her friend Alana was working. She made us a killer round of whiskey sours and finished off the night with a whiskey based concoction of her own that tasted even better. I like the drinking here. This is good people.

Day 10: The $150 Taxi

Weather wise, it was the worst day yet. But I was packing up to leave anyway. Iceland was an incredible place to visit, but I was ready to get back to the land of $10 burgers. That morning, I missed the shuttle bus to the airport because I didn’t read the ticket right because I’m an idiot. I was about to buy another one online and decided to get a taxi instead. That turned out to be a $150 mistake.

But I got to the gate on time, and flew out of Keflavik that afternoon. Expensive, though it may be, I made it work. I saved up for months, ate like a college student, learned to drive stickshift, learned to scuba dive in a drysuit, spent countless hours mapping out an itinerary line by line, and it all paid off in the end. I orchestrated ten of the most adventurous days of my life in one of the most magical countries on earth. If I can do it, so can you.

This story continues in the New Year.

Part 3: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

Part 3: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

…continued from Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

Day 5: The East Fjords

The northeast country was the most diverse terrain I had ever seen. I cleared a ridge in the morning, revealing the vast, open lava fields of the Skútustaðahreppur region. A huge plain of lava rocks and ash spread out across the land. It was everything Iceland is – picturesque, dark, otherworldly, like nothing like I had known. I grew up in a country with millions of acres of deciduous forests, foliage, deer, black bears, and catfish. But here, the calderas, hot springs, snowfields, and glaciers continuously shape the face of the land. It had the openness of Alaska and the emptiness of a lunar landscape. This country was a geologist’s paradise.

There was one particularly rough mountain pass that I cleared at midday to reach the coast. It was graded at 12% downhill on gravel, with switchbacks. The fact that I was still new to driving a manual transmission didn’t exactly help. I swore a lot as I turned at each switchback in a low gear, worried that the van would tumble off the road and roll down the mountainside. But I made it and the road leveled off as I approached the East Fjords, easily one of the most beautiful regions in the entire country.

I drove until mid-afternoon and stopped at the coastal town of Hofn. Natalie reported her status on Facebook. She saw the auroras a few nights ago. I was jealous, even though I had no reason to be.

I left the campground to get a drink at a nearby restaurant. When I looked at their expensive menu, I almost walked out. This restaurant had burgers for $40, a BLT for $40, and entrees going at $60 – prices which unfortunately aren’t that uncommon in Iceland, thanks to their huge tourism industry. But then I saw something better for less: Icelandic pancakes for $12. Now we’re talking.

They brought me a hot pancake with whipped cream, blueberries, syrup, and lots of decadence. I would do it again in a second.

Day 6: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

I figured out that I could stream music from my camper van’s wifi. When I plugged my phone into the dashboard USB, it played the audio through the van’s speaker system. Hell yeah? I wish I figured this out earlier. I loaded up an ambient Spotify playlist and drove the southeast coast to the likes of Hammock, Brian Eno, Caspian, Julianna Barwick, and others who would complement the open road. To me, epic landscapes like these always seems to bring out more depth and nuance in my music. And perhaps the music itself amplifies my sense of adventure as I wander into new lands. I didn’t know it at the time, but as the soundscapes were building and I approached the lagoon, this would be the most exhausting day yet.

I parked at the main lot of the Jökulsárlón Lagoon, a huge glacial lake on the southeast coast. It was one of three lakes that I planned to traverse that day in my packraft. But first, I wanted to see Diamond Beach. The glacier above the lagoon frequently calves, sending huge icebergs across the lake that eventually reach the mouth of a small river close to the road. They break up and wash downstream and into the ocean. The tide then washes them back onto the black sand beach, creating ice diamonds.

I went back to the van, got my gear, and hiked along the east side of the lagoon to find a good launch point relatively clear of the bigger icebergs. The rangers warned me that they could flip anytime, causing a bad accident. I paddled into the lake, far enough from what could have been a dangerous calving.

The Breiðamerkurjökull Glacier to the north was massive. On a map it is about 8 miles wide. There was no way I could fit it into a camera. I paddled across the lake for an hour with that huge glacier to my right and countless icebergs to my left. I got to the other side of the lake, packed up my raft, and started walking the marked trail between there and the lakes to the west.

The trail went over five miles of moraine, but felt like longer. Soon, I was on the higher hills, looking down at the braided streams of glacial meltwater that fed the lake below. The path was defined by trail markers that went on for two good hours before reaching the west end of Breiðárlón Lagoon. I planned to paddle it for a mile to the mouth of a small mile long river on the south end, float the river to Fjallsárlón, and hike back to the road from there. I easily paddled across the lake, luckily without any wind to complicate my route. In a packraft, the wind can take you in any direction it wants, and probably not where you want to go.

I reached the mouth of the river and scouted the rapids at the top. It didn’t look like this on the satellite. I expected to see an easy, floatable river between here and the lake downstream. But this river was fast with a lot of Class II. Well, I’m nothing if not adaptable.

I navigated mostly on center lines through the top rapids. I approached the third rapid about a half mile downstream and positioned for the middle to avoid some holes on the right. I thought I was cruising. Then out of nowhere, I approached a river-wide pourover ledge of four feet. Fuck, I should have scouted it. The swell went over and piled into a big hydraulic. I charged at it, hoping to bust through. No luck! It pulled me back in the hole and I flipped.

Luckily, there was no retention. I washed out of the rapid and went straight into another Class II. Shit, where’s my paddle?!! I spotted it 10 feet away to the left. It was partially submerged with one oar bobbing out of the water. That’s a first. I kicked for it and got it easily. Still pretty unnerving. I waited out another rapid, hoping for an easier break to self-rescue, and got back in just before another rapid was on. As it mellowed out, I scrambled into position and eddied out to the left to get my bearings. I got to the shore and stepped onto firm gravel. That could have gone better.

I love to run big rivers, but wipeouts like that one always freak me out. I wasn’t planning on running swiftwater at all that day. In this case, what looked like an easy float from the satellite was far from it. That said, it can be done if you mind the ledge in the middle to scout and/or portage. I didn’t do either, but I’m sure it has a runnable line.

The satellite said that there were two more rapids before it turned to the right and opened into the lake. I scouted them both and planned on a center line. Pretty much everything on that river was a center line except for that fucking ledge.

I was discouraged, but I kept going. I easily cleared the last few rapids on the river, and went around one last bend. The calming water carried me into the lake in full view of the Vatnajökull Glacier. She smiled back at me as I floated peacefully into quiet water.

I shored in, packed up, hiked back to the road, and eventually got picked up by a traveling German tourist.

This story continues in The Golden Circle.

Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

…continued from Part 1: Jetlag in Reykjavik, Diving the Silfra Fissure

“For all its material advantages, the sedentary life has left us edgy, unfulfilled. Even after 400 generations in villages and cities, we haven’t forgotten. The open road still softly calls, like a nearly forgotten song of childhood.” -Carl Sagan

Day 3: The Ring Road

I think every traveler should drive the Ring Road at least once in their lifetime. As the main highway in Iceland, it circles around almost the entire country, offering some of the most diverse and interesting landscapes you will find anywhere. I had considered the idea of a cycling tour around it, which lots of people were doing, but decided instead to drive its 828 miles in a vehicle.

Lots of people travel to Iceland, rent cars, and go on roadtrips around the country each summer. I didn’t want to stay at expensive hotels and didn’t feel like bringing my camping gear. Instead, I rented a camper van and spent six days driving, exploring, and sleeping. Equipped with a pullout bed, kitchen, stove, table, chair, wifi, and pretty cartoon decals, it had everything I needed to live for the next week.

I loaded my backpacks and suitcase into the van and drove out of the rental agency in the late morning on the beginning of a weeklong roadtrip around the island. But first, I made a stop down the road at the Blue Lagoon, a popular geothermal spa close to the airport.

I’m not much of a spa person, in case you haven’t guessed. But even I could appreciate that lagoon for its natural beauty and decadence. It felt surreal to float in the hot blue water, surrounded by piles of lava rocks. I almost wanted to put some of that exfoliating shit on my face. I didn’t do it, but it also has a fine dining restaurant, island bar, saunas, and massages, if you’re into that sort of thing. Thanks to the island’s geology, there are lots of hot pools like this one in Iceland, though this one definitely gets the most attention.

I got out, dried off in the sun, and drove northward through the city, planning to get to the north country by sundown. The highway in Reykjavik had a lot of roundabouts which were tricky at first to manage on a stickshift. I had just recently learned to drive in manual specifically for this trip. The rental company didn’t have any automatic cars, which I didn’t notice when I made the reservation earlier that summer. So it was either learn on my dad’s farm truck or I don’t get to drive in Iceland. A stressful, yet productive goal.

The road narrowed into two lanes and I left the city behind, going north along the coast on an uncharacteristically sunny late afternoon. I mounted my camera to the windshield to film a timelapse video of the drive. The shutter went back and forth hypnotically for hours as I captured many mountains and towns in the late day.

I turned east, ascending into the hill country, a region quilted in farmlands. I passed countless horse ranches and sheep farms that were almost never fenced in. Sheep wandered freely, sometimes onto the road.

As the evening darkened I drove up another big hill when my camera suddenly stopped. At a glance, the screen revealed “Error 20: A malfunction with the mechanical mechanism has been detected.” What the hell is this? I restarted the camera and turned the shutter interval back on. After a few minutes, it stopped again. I concluded later that night after Googling quite a few message boards that the shutter hardware was starting to wear out and it needed to be serviced. Well, shit. This wasn’t an option on this trip, nor was replacing it in Akureyri for $800. So it meant that I could only get drivelapse shots of the first day. Which was a shame, because this wasn’t even the best part of the road. But luckily, I could still point and shoot, so it was functional enough to be useful.

I arrived at the town of Varmahlíð and turned south on 752. I pulled into the gravel parking lot at Viking Rafting and parked behind the main building, and went inside to ask if I could camp in my van. Eight river guides and support kayakers were sitting on couches and watching an extreme kayaking documentary. I liked them already. After watching a video of two guys dropping treacherously through a slot canyon in California I went back to the van, cooked dinner, and slept. The light faded and the temperature dropped.

Day 4: The East Glacier River

Iceland would have lots of perfectly great, runnable rivers if so many of them weren’t punctuated by dangerous waterfalls. Although they’re great to look at, they’re not so great to attempt in a raft. An exception is the East Glacier River, an awesome Class IV canyon in the north country, where the waterfalls that once existed have been washed out by the continuous pounding of water. It was a river trip full of big hits, fast gradients, sheer lava rock walls, crashing hydraulics, and lots of noise and swearing – exactly the kind of river trip I was looking for.

I was one of three people who signed up to raft on the East Glacier that day, the other two being a newlywed couple from Canada. They had the right idea. If you’re going to honeymoon, you do it right. Do what I do. Go to Iceland, rent a car, bomb a river. We geared up in the main building and left in the shuttle bus for the river launch, 45 minutes on a dirt road from the headquarters. We arrived and sat next to the river while the guide gave us a 30 minute orientation on river safety. He emphasized that we needed to smile and have fun if we fall out to avoid panic – something I in my shortsightedness could have done better. More on that in a minute.

We put on our drysuits, walked the raft to the river, and eddied out into the current. The trip was supported by a kayaking photographer and two rescue kayakers who went out ahead of us in the bigger areas with throw bags and lots of river rescue training. I met support staff from Nepal, Uganda, New Zealand and Alaska – all living and working at the river outfitter for the summer season. Though we were all from different walks of life, there is one thing that always brings we river rats together: We love to run wild rivers.

The entrance rapids were fast and easy as the current rushed through the canyon on a high gradient. We floated past numerous sheer walls in a river 20 feet wide, sometimes less. The first big rapid of the day, Alarm Clock, threw a huge splash my face like a bucket of cold glacier water. We went around sheer bends of rock as the current tumbled its way through numerous Class III wave trains.

Commitment Rapid was next, and was a huge Class IV pourover that flipped the raft and threw all of us out. I felt the current pull my paddle out of my hand, and another rafter caught it as it washed out into the left eddy. Soon we were back in the boat for more. Game on.

After 20 minutes, we eddied out and the guide explained the strategy for Green Room, a technical Class IV triple drop. It turned out to be a monster. We didn’t even get the first drop correctly. The boat flipped again and I was back in the water, flying down the rapid. The current sent me over the second drop. One of the kayakers in the right eddy yelled something at me. I couldn’t hear him. The swell took me over the third drop and into a huge wall of foam.

I expected to wash out of the hole after a few seconds. That didn’t happen. SHIT! IT’S RECIRCULATING!!! I continued to tumble underwater in what felt like an office sized washing machine. Was I stuck in a recirculating hole? What the hell was going on? It felt like an eternity. FUCK!!! I’M NOT COMING UP!!! I need to get out of this now! On other whitewater trips they told me that if I ball up then maybe it will send me back out of the–

I’m out! I can breathe!!! The rescue kayakers were right there, almost like they expected to see me. “Swim to the eddy! Swim to the eddy!” I went for it, but was too tired. They had me grab on the handle on the back of a kayak and ferried me out of the current. The guy snatched something orange out of the water. It was my camera. It fell off somewhere in the middle of all of that shit. He let me go at the eddy and I swam for a rock on the edge. I clung to it as the water pulled at my feet and scrambled ashore – too out of breath to stand, but more alive than I’ve felt in years. Fucking shit, that was crazy.

Turns out I was perfectly fine. That rapid is called the Green Room because if you go far enough into the undertow like I did, you will find yourself surrounded in ambient green light. But without fail, it will eventually spit you out at the surface. I didn’t try it, but the Lower New River has the same feature called the Elevator Shaft. Boaters jump in, get pulled down, and come back up twenty feet away. The casual way the guides joked with me and the other girl who it happened to later was reassuring. I wasn’t really in any danger.

We eddied out to the left to take a break. I heated up my core temperature with hot chocolate and waffles with whipped cream, berry preserves, chocolate syrup, courtesy of a local farmer at the top of the canyon. For years, he has been feeding rafters at this spot. He used to climb down by foot, but at some point rigged a pulley system to lower the food to hungry, cold boaters. Every day. For years. That’s what he has been doing. I can’t even begin to describe how good of karma that is.

Later, we approached a big wave hole and our guide asked us if we wanted to surf it. Usually this causes boaters to fall out, which is often what the outfitters are going after. Because let’s face it, as scary as they get, the river wipeouts do make for the best pictures. I looked at the calm water right after it and thought why not. I already got pummeled upstream anyway, what difference does it make? Sure enough, we got tossed out and easily made for the right eddy.

Jump rock was next, a big 30ft cliff jump near the end of the canyon. I wasn’t intimidated by anything at this point.

The river slowed down and the walls widened, eventually sloping into hills and farmlands with higher mountains far off into the distance. It was calm, easy, scenic, and a great way to end a wild river trip. We packed up and went back to the headquarters where I got a CD burn of the camera boater’s pictures. The Floatie Back Door on my GoPro is the only reason why it wasn’t lost on the riverbed.

I had a few hours of good daylight left. I drove east. I went over a mountain pass, drove past the town of Akureyri, and camped next to Mývatn Lake, one ridge away from the vast lava plains of the northeast. The red sunset brought peace to an otherwise wild second day on the road. So much has happened. But I was just getting started.

This story continues in the fjord country.