The Camino de Santiago Part 5: Cape Finisterre

The Camino de Santiago Part 5: Cape Finisterre

…continued from Part 4: The Way to Santiago

The towers of the Santiago Cathedral are shrouded in morning fog. Leaving west from the plaza, I follow the Camino Fisterra, ocean bound, through the western edge of town past old oak groves and city trails. Santiago is quiet in the early morning, as is this trail compared to the big crowds I saw from the Sarria stage.

I didn’t give much thought to the elevation profile, or I would have expected the steep hike up the ridgeside of Mar de Ovellas at midday, which despite its difficulty has a spectacular view of the valley behind. Descending the other side, I cross the medieval Ponte Maceria, a picturesque 12th century bridge over the charging waters of the Tambre. Negreira, the largest town before the coast, is just a few miles further. I check in there for the night.

The path continues into a flat valley for half the next day, passing cornfields and cattle farms. Galicia is rich with agriculture, which is evident whenever I see a tractor go by or livestock wander through the villages. I like it in every way but one: All of the farms smell like cow shit. But I still enjoy the overcast day as the Camino leads me along the old farm roads. That night in Olveiroa, I reconnect with Choi the Korean Chef, the only other person from the Camino Frances who I have seen out here. It’s the first meal I’ve had with her since she made dinner for me and the others back in Leon. We have one last pilgrim dinner together with Diane from Australia.

From here, the trail winds into the mountains for half the day. I leave right before sunrise and hike along the ridge next to the charging Rio Xallas and its cascading waters far below. The morning sun lights up the mountain fog behind me in tones of orange before lifting and breaking up above the hilltops. I continue over hills and open fields as I have done now for too many days to count. Finally clearing one last steep ridge, the scenery changes.

Here, pilgrims have journeyed for hundreds of miles far from their homes to reach this place, where for the first time in their lives they see the vast blue horizon line of the Atlantic and the roar of the ocean. Steep ridges descend down to the water along a ragged coast, including those of the mythical edge of the world, Cape Finisterre, which is still a three hour hike away. I hike towards it, passing by coastal towns until I reach Fisterra, leave my pack at the aubergue there, and continue on.

Here at the south end of the cape lies the lighthouse, where the westbound pilgrim can go no further. Like a beacon, it stands high above the eastern harbor and the open ocean to the south and west on what was once thought to be the end of the western lands. To kill time, I hike up the ridge. From the summit I can see the lighthouse, Fisterra, and the neighboring towns, and I wonder how many pilgrims from ancient times continued on from Santiago to reach these shores at least once in their lifetimes – to watch the sky in the west change from blue to gold as the sun descends above the water.

Early in my trip, I spent a night in a village albergue just outside of Burgos where the abuela who runs the place told me something I would never forget just as I was about to leave. She said that as I walk the path of the Camino, that the Camino will show my own path to me. Which at the time I didn’t quite understand, let alone believe. I never doubted her sincerity, but how does something inanimate like a hiking trail show me anything that profound? And how do I find my metaphorical path? What does that even mean? And even though I doubted her at the time, her words stayed with me ever since.

Now I finally understand that she was speaking from her own life. That she too had hiked on these ancient roads on a wonderful journey of her own, maybe even more than once. And that the Camino itself revealed to her the next step to take in an incredible life adventure. And she believed that this powerful place could do the same for me – so much so, I think, that she wanted to see the same Camino in the eyes of each pilgrim who wandered through her hostel in that tiny village.

And I can’t deny how right she was as I watch the sun descend like a giant ball of fire over the horizon line of the sea. I think that there is something about this that resonates with me more than I will ever know how to say in written word, photos, videos, or anything else. I didn’t believe it, nor did I look for it, but that didn’t matter.

The Camino finds you. It calls you. And if you answer, it will show you your path.

Clouds light up above the red sun as it slowly falls behind the edge of the world, still casting a soft glow on the cliffsides while waves crash on the rocks below.

At last, as the curtain of nightfall covers the ocean, I get up and make my way on the trail back to the town in the fading daylight, already thinking about my next adventure.

Thanks for reading! This story begins in The Pyrenees!

The Camino de Santiago Part 4: The Way to Santiago

The Camino de Santiago Part 4: The Way to Santiago

…continued from Part 3: Crossing the Meseta

I have been hiking all day on a winding mountain road past little towns, highland farms, and wandering cattle. The terrain – and the weather for that matter – is a welcome change from the continuously flat Meseta and its April showers that consumed the last week of my life. I’m a few miles out from the Cruz De Ferro, an iron cross standing at the top of the pass just after the hillside village of Foncebadón. I check into an aubergue after a hard day uphill.

Many pilgrims regard the Cruz De Ferro as an important place to address the burdens in their lives, symbolized by a stone that each person brings with them on their journey. They hike for hundreds of miles, carrying their stones and the emotional weight of their hardships that it represents to this summit, cast their burdens at the foot of the iron cross, and continue on, hopefully in a better state of mind and heart. I too had my stone that I carried with me up this mountain. In my case, my burden was guilt.

There was a family dog who I neglected in my teenage years when he needed me. We didn’t know how to handle such a wild dog, so we left him chained up in the yard most of the time and I became busy with other matters. Eventually my family brought him in the house when he was older and calmer, but it was long after I had left. Only later in life did I realize the weight of my mistake – not being part of his life – far later than I would ever have the chance to repair. Before I started my journey, I went to his burial site at the family farm and picked up a stone. I have carried it with me, and the weight of my guilt, on the Camino since the very beginning. Now, I stand at the cross at the top of the mountain, I take it out, determined to never treat another family pet, or any animal, like that ever again and I cast it onto the pile.

The descent from there into the Ponferrada valley entails about three hours of steep, rocky downhill trails before leveling off at the valley floor. It isn’t much fun, but the view is great and the morning is pleasant. Flowers appear along the forests, soon blooming across entire hillsides. I try my best to enjoy the morning without twisting my foot on the rocky trail. I reach the bottom and stay in Molinaseca at the valley’s eastern edge for a night and then continue across the valley for an entire day through Ponferrada’s city centre, going west to the postcard town of Villafranca. The path leads me through gentle rolling hills, vineyards, and hazy mountains in the distance.

I meet Becky from LA, eating dinner by herself at a terrace and just starting her Camino. She has questions about logistics, like how easy is it to find available aubergues, should she make reservations, what the heck is she doing out here, etc. I was nervous on my first day too. Next morning, she already passes me at a faster pace. She’ll be fine.

After Villafranca and its beautiful Castillo, the trail follows a rushing creek along another big uphill ascent to O’Cebreiro, the second highest point of the Camino. Leaving the main road behind, I hike steeply up the large ridge for about three hours, soon revealing spectacular views of the valleys below. The Galician border is marked by a large sign at the summit of the pass. Becky catches up and we team up, hiking in and out of the mountaintop clouds before we reach her planned stopping point. I stay in the next town after and we keep going west the next day, hiking downhill out of the mountain fog.

Something dawns on me as I descend on the western side of the pass, going by countless villages and tattered yellow arrows: For the first time ever, Santiago is about a week away. This place that I spent years dreaming about was actually materializing – the end of all of this, by the gods, is in sight. And I don’t know how to handle it. Because up until now, I have been dealing with nothing but frustrating delays and setbacks.

For seven years, ever since I briefly dated somebody who hiked it, I was fixated on the idea of doing the Camino myself. I started learning about it, obsessively watched Youtube videos, and even bought a guidebook and outlined it at one point. My obsession snowballed into my first nervous decision to travel to Spain in 2018. Unfortunately, I realized then that I didn’t have the money to take the trip after paying for some unexpected dental work. I couldn’t meet the budget at that time, and I don’t travel in the red.

I tried again in the following spring, but canceled my trip last minute because I couldn’t find comfortable hiking shoes to work with my widening left foot. It’s possible that I could have used what I had for distance hiking, but I’ll never know. It was a situation fraught with anger and disappointment. Instead, I traveled around Europe for three weeks, visiting different countries as a contingency. To an extent the unexpected micro-adventures brought comfort and healing, but it wasn’t where I really wanted to be.

The third time I attempted the Camino was in the fall of 2019. I successfully hiked for the first third of the trek, finishing at Burgos with the intent on returning the next year to reach the end. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the foresight to anticipate an imminent global health crisis that might well complicate my plans.

The fourth attempt was derailed in 2020 by worldwide Coronavirus lockdowns.

And the fifth time? Well, that was my decision. It was the fall of 2021 and tourism was allowed again in varying degrees between America and the EU. The problem was that even though travel was allowed for vaccinated tourists, I could still be exposed to the virus – and if so, be required to quarantine for 10 days in a hotel. But where? How does it even work if I catch the virus in a remote village without any hotels? Further, I would also need a negative Covid test to return to my own country. And if it fails, I could end up in Quarantine Gulag for that as well. It led me to the conclusion that we as nations really didn’t have a grip on this problem yet. And places like Spain were allowing just enough people to keep their tourism industry from collapsing. Which I understood, but I realized I didn’t want to be dealing with so many unknowns. Is this how I’m supposed to travel now? Wondering if and when I get sick? As painful as it was to come to terms with it, I felt rushed and ultimately wrong in doing this. And so, once again, my Camino was delayed. This time by my own choosing.

And this time, I broke my own heart.

Well, that’s in the past. It’s a perfect sunny morning in the forest after Sarria. I got out of the mountains a few days ago and Santiago is closing in. Despite all of my sadness and hesitation, I’m not slowing down. Rather, I’ve been starting each day with a surge of pure energy. The weather is perfect and the hill country out here is gorgeous.

Galicia is noted for its lush forested hills, farms, and towns of ancient stone buildings, some converted for modern use. Others are left to crumble in time and the overgrowth of the forests. Going from to village to village each day, I’m reminded continuously that despite all of its modern advancements, Galicia bears the history of great kingdoms, old forests, and lovely hillside vistas that have stood throughout the ages. This place feels like a Shire by the sea.

The main cuisine out here is mariscos and pulpo caught from the coastal towns. That along with the local wines, which are always cheap, are perfect after a long hot day. I stop at the famous Pulperia Ezequiel in Melide, and then a cervezeria selling Pilgrim Beer, on my last day before reaching Santiago. Continuing past other bars and cafes, I see numerous people drinking together. They’re not in a hurry. Because tomorrow they will get to the end. And they don’t want tomorrow to come. We don’t want this dream to be over.

I keep seeing Becky, Ginger, Nick the Brit, the Canadian Ladies, and Dan the Storyteller, whenever I stop in the towns. I call him that because he started calling me Dan the Cowboy because of my hat. But every time I see him, he recalls some kind of interesting anecdote from the people he meets. He said he saw one guy on the trail with a cloth photo of a man’s face on his backpack. When he asked him what it was, the guy said it was a picture of his father. And that before this, his father had hiked the Camino eight times. This time would be his ninth.

Another time, Dan met somebody who was carrying a small pack in their front. He told Dan that it was the ashes of his mother. That she always wanted to hike the Camino, and now they were doing it together.

Back in Villafranca, several of us shared a terrace behind an aubergue with a young Spanish lady and her father. She said that he was hospitalized a few years ago with a severe case of Covid that almost took his life. After he recovered, he said to her, “I want you to come with me on the Camino de Santiago.” And there they were.

And then there is the story that I heard from my archive of YouTube videos about a young woman from South Africa whose father was murdered right in front of her. For her, the Camino was her way of working through her trauma and healing from the pain.

I’m sure there are so many other tales like this. So many kind, simple, genuine, broken people – in person or in spirit – who are out here on a journey for a myriad of reasons. We each have something calling us to walk together on this ancient Way of Saint James, ultimately bringing us each to the outskirts of Santiago de Compostela. Here, I choose to spend the night in O Pedrouzo, a half days walk from the plaza.

And so, Santiago is finally in sight.

I start early the next morning, and whatever sadness and hesitation I felt about this place is gone. I’m charging harder than ever through the outer suburbs with an incredible wave of energy like I have never felt in my life. I am unable to slow down or stop. It feels like an invisible wave of energy is literally pushing me from behind. For four straight hours. I can’t put the reasons why into words, but I want to reach the end as fast as I can. My pack is the only reason why I’m not running.

Passing the outskirts of the city centre, I see Kirstie from Scotland, who for the last few days has been limping painfully on an overused, swollen ankle. I saw her early yesterday and was worried about her, but it looks like she’s about to hobble gloriously over the finish line. Which I understand. At this point, something has to physically stop us from reaching the end of this dream. We chat for a bit, and I tell her I’ll see her at the plaza.

HOLY SHIT!!! IT’S THE TOWERS!!!! The spires of the cathedral stand out above the rooftops. It’s only blocks away.

Finally, I descend a stairway and walk into the plaza below the façade of the mighty Santiago Cathedral, unable to hold back my tears. The towers cut sharply in the brisk morning sky. This whole place is full of pilgrims celebrating: relieved, sad, joyful, and victorious people pouring into the plaza all day long. I find a few of my trail friends near the middle, like Caleb the drinking Irishman, the Israeli who reminds me of Borat, and Becky and Ginger arriving soon after, and Kirstie, limping in pain and glory. Below the overpass coming into the plaza, a guy on a bagpipe starts playing Amazing Grace, and with it, a reminder of home. I’m losing it.

Santiago was a lifetime away. But not anymore.

That night, pilgrims and locals of faith alike come together in the cathedral to attend the Pilgrim’s Mass. I don’t find out until later that the priest reads the name of each pilgrim who received their certificate at the Pilgrim’s Office in the last 24 hours, which must have included me. But I sit in awe of this immaculate, beautifully adorned sanctuary as he leads the congregation through each prayer from the high altar. I understand very little, and am certainly not familiar with any Catholic prayers and traditions, but I, a Pilgrim of the Camino, am welcome among them. The priest ends the mass with a beautiful prayer and blessing to the pilgrims.

I stay in Santiago another day, as some of my friends like Becky, Ginger, and Kirstie the Limping Scotsgirl, have already left town. But a few people like Dan the Storyteller and Nick the Brit are still around. Then there’s Vivian the Filipino, who was apparently around the whole time, but I only met her yesterday. We find Silvia from Italy at the plaza that evening and invite her to join us for mariscos and wine.

We’re about to end the evening when we pass by another group of pilgrims, already drunk and on their way to the next bar. They became a wild, close group of best friends ever since Pamplona. Before I realize it, we’re all drinking together. Cassie from Australia found them weeks ago. She tells me how she went through an extremely difficult situation in her personal life before coming out here and being swept up in her friendships with them. At the next bar, a guy on a guitar is singing cover songs. Everybody in this room has a smile. Pilgrims and locals alike are singing and dancing. Two of them are in love. I’m on my fifth drink as the guy sings La Bamba and everybody joins in.

And so, together in a tiny bar under the vibrant city lights of Santiago, we celebrate into the beautiful night. I can’t think of a better way for each of us to bring this crazy life adventure to its cathartic and inescapable end.

Only for me, this is not the end and my dream isn’t over. And so as the new day begins, I continue on the path going west out of the city.

This story concludes on the shores of Cape Finisterre.

The Camino de Santiago Part 3: Crossing the Meseta

The Camino de Santiago Part 3: Crossing the Meseta

…continued from Part 2: Pamplona to Burgos

I return to the cathedral and continue west out of the city. Following the riverwalk along a nice grove of trees, Burgos is awfully quiet. This is because it’s the end of the Semana Santa, the Spanish Holy Week and today is Easter Sunday. At 10am everybody is inside the churches attending Mass. And though I could count the number of locals on the street right now, I would find out later that the main plaza will eventually be packed wall to wall with people.

Going out of the city, the path winds uneventfully west along the highway for the rest of the day. Neither I, nor my gear, feels broken in – something that I lost by splitting this trip into sections. Having landed from a redeye flight into Madrid early this morning, my body thinks I stayed up all night as I hike into the afternoon, drowsy and exhausted. I expect my hiking schedule will force me out of my jetlag sooner than later, but right now I would rather lay on the grass than cross another bridge or pass another marker. I check in at the little town of Rabé de las Calzadas, where the only lady in the building stamps my Pilgrim’s Passport, the first of many to come.

Going west, the terrain crosses numerous hills and plateaus in the following days, with huge open vistas and often little protection from the erratic weather patterns that I should have expected in Mid-April. Clouds and scattered showers roll across the countryside as I approach the town of Castrojeriz on the fifth day. It is situated on the side of a large hill with a castillo at the top. I have time to kill that afternoon and leave my pack at the aubergue to scuffle up to the summit. The overlook across the valley is spectacular, revealing the quilted terrain of farms spanning out across the plains and rolling hills far into the distance. Wind is fierce, blasting me in the face each time I look out from the castle walls, but I don’t care.

Hiking on, the chilly wind continues over more exposed ridges under grey skies. People try to ignore it and take selfies on the windy face of each dramatic hilltop overlook. As I climb and descend these huge, grassy hillsides, I feel the sensation like I’m in the middle of a vast green ocean, with swells slowly rising almost enough to break but never quite getting there. Eventually these hills will level into the flat plain of the central Meseta, where I plan to hike for about a week.

Others are out here too. Though we almost never hike at the same speed, I start to recognize more people whenever I stop at a café or hostel. So far, I have met Karen the funny Belgian, and two Germans, one of whom looks like an older Johnny Knoxville. We sit together in the evenings, exhausted, eating pilgrim dinners with some hearty combination of meat, potatoes, wine, and pastries. Karen especially makes me laugh, often being the kind of person who makes others laugh more at their own jokes.

For the most part, the weather is okay during my first week. Well, nothing great in life comes easy. And for every great high point in life that I achieve, there must be a time when my circumstances amount to an absolute, unmitigated pile of shit. Out here, it manifests in the form of what appears on the radar to be the remnants of a huge tropical depression poised to cover the entire Iberian Peninsula. It’s going to start tomorrow and continue for an undetermined number of days.

With no practical choice but to continue on, I leave the little town of Carrión de los Condes in the morning in my rain gear. The first few hours are bearable as clouds and scattered showers roll across the path, and are easily ignored. Continuing into the Meseta’s flat open farm country, hills and mountains farther off are obstructed by the fog and rainstorms. One in particular is closing in from the south like the arm of a giant beast. This dark wall of rain looks like it will get here in about 20 minutes. It hits us sooner.

With nothing protecting us as we hike on a straight road through the open countryside, the rainstorm pummels us with lateral gusts of wind and hard, cold rain pelting us in the face. Hours go by as we each push ourselves through the monsoon, rushing water, and puddles on the dirt road. It reminds me of those nature documentaries where they show those lines of penguins waddling through an Antarctic blizzard. I look down and see shards of sleet on my jacket.

I hate to stop, but I have to go around a bush to pee. I struggle, shivering, to get my fleece gloves off of my numb fingers, and for a second I wonder if my own dick is frozen.

This goes on for ten miles. With no respite. Finally, I descend a hill and see a café at the edge of a small town. It’s crowded with pilgrims trying to get out of the rain. Everyone has a blank look of shock on their faces, like they’re trying to process what the fuck just happened. I find Karen and the Germans and try to warm up with a café con leche.

After two more hours of the same, I finally get to my aubergue. Both my Pilgrim’s Passport and my real one are soaking wet – turns out my rain cover wasn’t enough out there. So I check in, wondering if it’s still valid for border crossings – a question to eventually bring to the fucking embassy in the coming weeks.

That was my day, how was yours?

I leave the next day as the harsh winds continue from the southwest, though the rain seems to have let up slightly. It picks up again around mid-morning as I pass through Sahagún, the official halfway point of the Camino. A nice old abuela gets out of her car. She sees me and yells “Buen Camino!” making me feel encouraged as I continue on with this punishment.

I forget that the Camino forks into northern and southern routes and I lose a couple hours by hiking on the wrong one. Backtracking for hours east, south, and west straight into headwinds and scattered showers, I reach the aubergue, get dinner, and crash.

And then all is quiet. The rain system that ruined the last two days (and maybe my Passport) has moved on. And so has the wind, leaving barely a breeze behind for the next morning. I go back out on the street at sunrise and continue into the country. Sierras in the north are completely covered in snow, reminding me of Colorado. They’re in full display for the whole day as I continue across the drying landscape. I’m set to reach León tomorrow and I’m making an extra five mile push reach a town aubergue just outside of the city.

I want to get to León early and rest for the day. So I leave an hour before daybreak the next morning, hiking slowly on the path under the stars. Behind me, a sharp yellow crescent moon rises above the quiet farmlands. Slowly, a red glow brightens on the eastern horizon, the stars above fade away one by one, and a new day begins.

I reach the city centre of León at mid-morning, and enjoy the rest of the day walking around the main plaza next to the cathedral. There are three of us at the aubergue – me, an older German lady, and Choi the Korean Chef. She invites the host and fixes the three of us a bibimbap dinner, with more than enough protein and rice for everybody. It’s a welcome break from all the great serrano ham and queso bocadillos I’ve been eating since I got here. As it is with this Camino, the dinners often become an exchange of cultures, cuisines, experiences, and the shared ethos of goodwill. Because while we each walk this path for ourselves, we also share a part of whatever this is with each other.

I go out to get something from the supermarket. As I’m walking by a tavern at the main plaza, Kirstie from Scotland waves at me and yells my name. She’s at a table with twenty other people and points to an empty seat. They’re all pilgrims. And they have been drinking here for five hours. What I think started as a small group turned into a party as more and more familiar faces found the table.

There is wine. There is food. There is each of us – all pilgrims celebrating together that we have gotten this far. To the backdrop of the huge cathedral just across the plaza.

“Do ye know tha Space Ghouls?” Kirstie asks me.

“Huh?”

“I said do ye know the Spice Girls?” This is her test to see if people can get past her thick Glasgow accent. I didn’t pass.

Kara the Canadian sat across the table. She ended her Camino at the halfway point a few days ago after some foot problems. The rainstorm was her breaking point. She intends to come back. There was Caleb the loud Irishman, Nick the Brit, the Israeli who reminds me of Borat, and so many others, carrying on into the evening. I decide after a few hours that this is great but I should get going. I have a big day tomorrow and I don’t want to ruin it with too much wine.

Speaking of wine, I had ordered about five or six glasses over the evening and then asked the server to bring me my check. For the quality and quantity, I would easily be paying at least $80 at any wine bar in Chicago. He brings the ticket back and I look at it. 6 Euros.

It’s a full day hike from León to Hospital de Órbigo. The clouds are back, threatening to ruin my day again with more rain showers. By mile 15, my feet are beyond sore and hurting with each step – not enough to warrant anything serious like an evacuation, but enough to get into my head and distract me from this lovely fucking countryside. To make it worse, the bottom of my left foot gets spasms if I hike on it for too long when I’m out of shape, causing my toes to clench together. This has already happened a couple of times out here when I hiked farther than my body wanted me to. Well, sometimes my body needs to listen to me. So I keep going.

After what was an hour of pain and felt like longer, I reach the iconic Puente de Órbigo, a long bridge of many arches crossing a river into the town. I’m exhausted, but not so much that I don’t appreciate such an impressive medieval landmark. Even if the cobblestones are hard on my miserable feet. I check into an albergue in town just as soon as another downpour starts.

It’s day 24. And a perfect bluebird morning. I start out at sunrise and make my way past the little town of Villares and the edge of the plains. As I hike into the hills, I look back one last time at the vast plains of the Meseta, green and hazy in the sunlight of the morning.

I follow the winding road into the hills. Two hours later, I reach a cross on a hilltop looking over Astorga, a city like so many others noted by its centuries-old winding streets, vibrant plazas, and magnificent cathedrals. Beyond the city is the backdrop of the western mountains, slowly changing in colors under looming springtime clouds. Somewhere out there, the Way to Santiago continues on a hard gravel road, beaten down each day by the feet of a thousand pilgrims. It still feels like a lifetime away – and it will until the day when it’s suddenly not – but I’m energized and hopeful as I descend the hillside and make my way into town.

This story continues on The Way to Santiago.

Reserva de la Biósfera Mariposa Monarca

Reserva de la Biósfera Mariposa Monarca

What if I told you that there is a magical forest in central Mexico where millions of monarch butterflies migrate to from North America every cold season? What if I said that when the sun reaches the trees each morning, you can see them wake up and fly down the mountainside by the thousands? Would you believe me if I told you such a place exists in the highlands of Michoacán? Because it does. It is the famous Reserva de la Biósfera Mariposa Monarca, an enchanting forested sanctuary where legions of butterflies look to escape the cold winters of the north each year.

They converge around eight colonies throughout the mountain range, two of which were in short driving distance from the centrally located pueblo of Angangueo. I reserved a hotel there on a Saturday in Mid-February during the peak season. Leaving early that morning with mi amiga Itzel, we drove south from Queretaro for three hours and reached the town at midday, optimistic and unsure of where to go. We asked around and eventually kept driving further into the mountains. Sierra Chinca, a colony eight miles further, was just ahead. Itzel drove nervously around switchbacks and steep hairpin turns, but we know that whatever was waiting for us at the top was worth it.

We parked near the trailhead and got out. The path led us through an open field and upward into the forested side of the ridge. It wasn’t a particularly hard trail, except for the fact that it was at about 10,000ft and we were both struggling to find our breath. One saddle crossing brought us to the other side with a great view of the western valley farther off. But still no butterflies. Did all the people scare them off?

Soon we reached the end of the trail and the “Quiet zone” next to the colony. Above, groups of butterflies fluttered and glided slowly among the treetops under grey skies. Other than that, there wasn’t much to see. Hoping for better luck tomorrow, we made our way back to town.

The other colony, El Rosario, is west of the town up the side of a steep ridge. The road leading us there had a great view, despite all of the potholes and scary turns without any guardrails. We drove slowly through it, hoping to get to the trail when it opened at 9. Late by 30 minutes, we wanted to beat the crowds and failed, but at least it wasn’t hot yet when we started hiking. This trail was painfully steep and the air felt even thinner than yesterday. Will I get altitude sickness before I get to see my butterflies? If that happens, I want a refund.

After about an hour of pain, the trail leveled out near the crest of the ridge. We reached the quiet zone about 100 feet away from the colony. Huge clusters of butterflies hung on the tree trunks and branches, still waking up. I read that enough of them hanging on a branch can create enough weight to break it. A crowd of about 100 people stood quietly in the main area, waiting for something big to happen.

I wasn’t sure how well the crowds would be regulated up here, but the park employees seemed to keep a good check on everybody. One them held up a sign reminding us not to talk, and the trail was roped off with signs everywhere, as to discourage the idea of people getting too close. They did well to make sure the butterflies had their space. Which is good because this park draws a lot of people in the peak season.

Soon, the morning sun broke through the treetops and started shining on the clusters of butterflies. One by one, they awakened with a flutter and began their day’s objective to find water and nectar. We started our way back down. As the ridge side brightened, they flew in countless numbers down the mountain hollows, many passing right by us. It went on like this for the next hour, all the way back to the visitor center, one butterfly after another. The forest was alive with them. They were everywhere.

When we got to the parking lot, even more of them went flying by the car. They continued passing by us as we drove out of the park.

The Great Dinosaurs of Cabazon

The Great Dinosaurs of Cabazon

I drove west on a busy three lane interstate just east of the LA suburbs, trying to navigate around too many 18 wheelers to count. The construction barrier on the right side threatened to scrape my rental car and send me flying into the other lanes. There wasn’t much to see in this valley besides the loud, crowded highway and all of the traffic trying to get through it. On any ordinary day I wouldn’t be driving in this unremarkable corner of Southern California. But this was no ordinary day. In fact, I waited my whole life for this moment.

Just off of I-10 west of Coachella is a small roadside stop known as the Cabazon Dinosaurs, featuring huge replicas of a brontosaurus and tyrannosaurus looking over their dominion of visitors. They became iconic to many kids in the 80s and 90s – myself included – for their role in important scenes in Pee Wee’s Big Adventure and The Wizard. Now, they’re the main attractions in a dinosaur park, where you can walk among smaller dinosaur exhibits, browse two different gift shops, and best of all, look out from the mouth of the T-Rex. As I drove towards the sun among thousands of other cars, the silhouette of the T-Rex came into my view, looking like a tiny plastic toy that I used to fight with a triceratops as a kid. I was already losing it.

In the film, Pee Wee Herman found this place at a frustrating time in his quest to find his stolen bike, where he no doubt wondered if the challenges he faced on the road made any difference. Out of nowhere, a truck driver helping him turned out to be an apparition of the late Large Marge, scaring the shit out of him and leaving him stranded by the road. He came upon the figures of the Cabazon Dinosaurs, glowing serenely in the late night. There was no doubt some encouragement in this, and at the very least, some cool shit to look at. He went into the Wheel Inn diner and made friends with the waitress Simone. They stayed up the rest of the night in the mouth of the T-Rex, making something of a connection bordering on attraction.

The dinosaurs were also part of a big scene in The Wizard, another cult movie from that era. Two young brothers, Corey and Jimmy, ran away from a broken home and made their way to the West Coast. Jimmy, a young shy kid of few words, repeatedly said “California”, motivating his brother Corey to sneak him out of a behavioral institution and start hitchhiking west. They met a fiery redheaded girl named Haley, played by Jenny Lewis, who figured out that Jimmy was a Wizard at video games. They made it into something of a hustle, with Jimmy eventually winning the national Nintendo competition at Universal Studios. The family finally caught up with them and started driving back after celebrating.

They passed by the dinosaurs on the highway. Jimmy saw them and started yelling “California! California!” The family stopped and they went inside the brontosaurus. Here, Jimmy revealed the reason for his obsession with California. It wasn’t to escape from his problems, or to win at Super Mario 3, or even to be in California. Those things he did for his brother. It was because he lost his twin sister two years ago, and his fondest memory of her was right there, among the Great Dinosaurs of Cabazon. He took out a family photo of them in front of the dinosaurs and left it inside the brontosaurus. Then the family agreed to bring their boys home.

As a result, the dinosaurs found their way into the imaginations of kids like me, and over time, into nostalgia. But it didn’t matter that I was all grown up as I drove into the parking lot that day – the 7 year old me was losing his fucking mind. These were the Cabazon Dinosaurs who I had spent my entire childhood and adult life wondering if I would ever have the chance to see. And so this wasn’t just a visit to a road stop or some half assed tourist attraction. This was something far greater. This place was hallowed ground.

I bought a pass at the ticket counter and entered the pathway behind the T-Rex. Dioramas displayed many smaller life-sized dinosaurs, like a pair of velociraptors of eight feet (Spoiler: They look just as vicious in person as they were in Jurassic Park). There was a sand pit off to the side where kids could dig up “fossils” and win free prizes at the gift shop. The path led to the tail of the T-Rex, where a door opened to the inside. Following a stairway up to a small spiral staircase, I reached the inside of the mouth of the beast. And I could look out and see the park below. Sunlight beamed through the teeth – perhaps the last sign of daylight I would ever see if this animal were real.

Outside, the sign of the Wheel Inn Restaurant was the only thing left of that famous diner. They bulldozed it to the ground several years ago, which is bullshit. But I did enjoy walking underneath the brontosaurus, where Andy chased Pee Wee in circles around its legs before he escaped on a passing train. It also had a door leading inside to a gift shop. There, baskets were full of dinosaurs of all types and sizes. They could have easily been added to my collection for some epic dinosaur wars in my basement.

As I drove east, the Great Dinosaurs of Cabazon vanished behind me. A stark full moon rose above the northern mountains against the lavender colors of the early night. I thought that it wouldn’t be much longer before those dinosaurs were glowing beneath the stars of the Southern California desert, as surely they were.

Classic U2 Album National Park

Classic U2 Album National Park

In a great way, Joshua Tree is an odd place. Located on a big plateau in the middle of the Southern California desert, this park is full of strange looking monolithic rock piles and thousands of gnarled Agave trees sticking out of the earth. It is a park for the hiker, the rock climber, the explorer, the tourist, or all of the above. But preferably in the cool season. And now it was the park for me, after what turned out to be a failed Mexican Visa attempt in Yuma. Doing my best to turn disappointment into action, I rented a car the night before and made the three hour drive to the park at daybreak.

It’s a big park that can easily take a week to reach the other side in a backpack. But I only had about half the day to see it, so I researched what seemed to be the most eventful looking area for a day hike. I decided on the Hidden Valley area and started driving for the south entrance. I don’t know if it was a coincidence, or if some higher power was trolling me, but when I turned off the exit of I-10 for the park road, U2’s “With or Without You” started playing on the radio.

I drove north for 40 miles over two mountain passes and valley floors. Joshua Trees appeared – first small, but getting bigger with each mile until they were easily 10 feet high. Soon, I reached the parking lot at Hidden Valley and got out. For the next three hours I hiked around the rock piles and pathways along the valley. After a while, it started to feel like I was walking in an ancient garden. As if it were ruins of some age-old civilization who left their monuments behind, only to be covered in sand and stone – yet leaving a legacy to these trees, who somehow thrive in the dust.

The surrounding rock piles drew climbers of all skill levels for bouldering and harness climbing. I saw young kids slowly going up small boulders with trained instructors above mattresses. Other people repelled down rock cliffs easily 200 feet high. Everywhere, people were scrambling over rocks. It was like Mother Nature’s jungle gym. Even I tried to find a small boulder pile to look out over the valley above the treetops.

Despite the enchanting landscapes in this park, the mid-afternoon sun reminded me that I haven’t acclimated to the southwest. Not even in December. I drove out, leaving this strange plateau behind. I needed to reach the Cabazon Dinosaurs by the golden hour.

I have climbed the highest mountains

I have run through the fields

Only to be with you

I have run

I have crawled

I have scaled these city walls

Only to be with you

But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for.

The Pictured Rocks Thru-Hike

The Pictured Rocks Thru-Hike

I was due for a return trip to the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore to take a thru-hike of its 40 miles of pristine coastline. I hiked and kayaked the Chapel Basin section of it last year and knew I needed to come back, having barely seen a quarter of the shore. I got a backcountry permit in mid-September, hoping for a likelihood of clear weather on the edge of the shoulder season.

I arrived on the west end near Munising and parked at the Sand Point trailhead with a five day itinerary. It was the late afternoon after a six hour drive from Chicago. I began hiking three miles to my first campsite as the evening sun beamed through the trees. The forecast predicted some ugly weather in the coming days, but right now the day was calm. I reached the Cliffs campsite, set up my tent, and went back to the shore to watch the sun descend over Grand Island.

I woke up the next morning to the pelting of rainfall. The downpours had already started, and didn’t let up for three more hours. Which wasn’t the best timing, since the only available campsite I could find was fifteen miles away. As the sky finally lightened, I packed up and continued on the trail. Gradually it went along the beaches and steadily rising cliffside. Off in the distance, the high bluffs of the Chapel Basin gradually approached.

Crossing Mosquito Creek at midday and continuing along the Chapel Loop, I hiked the uneven terrain, already exhausted. Still, it was worth it to see all of these cliff points and overlooks again. Sunlight was spotty across the lake and isolated showers rumbled across the water some ten miles off. It was okay now, but was the kind of weather that could change in a flash. Passing Grand Portal Point, a rainstorm hit all at once, sending me and the day hikers rushing away from the exposed overlooks. Sheets of mid-afternoon rain blew in gusts, obscuring far off cliffs as the waves crashed and roared below. I paced along the winding cliffside trail, feeling wiped out and delirious. I needed to eat.

Stopping at Chapel Rock, a prominent site on the far end of the basin, I felt better after getting food and a much needed break. The rock and the cliffs beyond stood backlit in the clearing weather.

I really wanted to set up camp and stop. But since the sites around the Chapel Basin were in high demand, the only available site I could find was four miles further. Which would have been fine if my legs weren’t already sore and bordering on pain. Well, I can keep bitching about it on a downed tree, or I can get to my campsite before dark.

The sun was out again, beaming in golden tones through the forest in the late day. It was that time near the end of the warm season that’s not quite the summer or autumn, but it’s some of both. There were warm days, and yet, leaves started to wilt and turn yellow on the edges of their trees. Fiery maple leaves lay scattered about the trail. And though the sun was out, it felt dim, as if it was telling us that the bright season on this rocky coast was nearing its end.

With about three miles to go, my calf muscles were getting tighter than I was comfortable with. I stopped and looked at my right calf. Shit, it’s getting swollen! I needed to find my campsite and figure out what to fucking do. The Google Maps marker said it was a quarter mile back. What? Where the fuck is the campsite??? Did I miss it? Should I turn around and look for it again? With an hour of sunlight left and potentially fucked up calf muscles, I didn’t have the leisure of wasting any time. I charged on, exhausted and bordering on panic.

There was a connector trail about a mile ahead, and I at least needed to rule out that it wasn’t somewhere before that. So in a panic, I kept going. It turned out to be the right decision. Just a few hundred feet from where I lost my mind was a sign reading “Coves – Individual Campsites”. I hobbled along the side trail, found my site, and set up my tent.

Not sure what to do about a swollen, overworked calf, I asked some other hikers for advice – notably to read whether or not any of them seemed alarmed. None of them did. They said to take Ibuprofen and apply the RICE method. While there was no ice to be found, rest, compression, and elevation could be done. For good karma, a kilted fellow gave me an ace wrap to reduce the swelling.

This day was equal parts beautiful and ugly, but it was finally over.

I crawled out of the tent the next morning after more rain, and was immediately shackled by my calf muscles tightening overnight. I expected it, but I was still surprised at how tight they were. My body was mad at me over yesterday. But was I well enough to press on? I was about to find out.

My trekking poles, I learned, could be used on my leg muscles like a foam roller. Which was absolute hell. With that and stretching, they loosened up enough for me to walk slowly. The good thing was that the next campsite was only 7.5 miles on a mostly flat trail along Twelvemile Beach. So as long as I took my time and took frequent breaks, I would probably be okay. I said happy trails to the kilted fellow and his friends and continued east.

Moving on slowly, I found a pace that didn’t seem to aggravate my calves any further. It allowed me to focus on other matters, like the wonderful fucking weather. I guessed that a low pressure system was passing on and in its place was a full day of brutal lake effect winds. I welcomed any chance to hike in the trees away from the brunt end of the shoreline wind. For much of the day, I was exposed to 30mph gusts of wind blowing off of the shore. Waves farther off were easily breaking at 8 to 10 feet – the kind of conditions that will prompt a gale alert by the local weather service. I learned later that Lake Superior can get much worse. I wasn’t surprised that this area has its share of shipwrecks, earning it the maritime nickname “Graveyard Coast”.

At one point the trail went out of the woods, exposing me again to the wind as I passed by a cute thru-hiker going the other way. Over the loud gusts of wind, I yelled “Nice day for a hike!” She yelled back, “Oh yeah, it’s beautiful!” I wasn’t sure if her comment was from the same place of exhausted sarcasm, or if she really was able to see beauty in the chaos.

I got to Sevenmile and set up camp, well protected from the wind. And my calves? Well, they weren’t better, but at least they didn’t get worse. That will have to do.

Then I woke up at 2am. The air felt dry. I looked out from my tent. Treetops were still, and the stars returned far above the forest canopy. I got back on my pad and slept soundly to the rush of Sevenmile Creek.

Right before heading out, I shared the firepit with Ashley, who was trying to light a bundle of damp kindling. She told me she was walking along like an old granny yesterday with her sore, blistered feet. Luckily, I figured out how to avoid blisters ever since the Camino, but soreness was another beast of its own. I think we all go through these challenges in backpacking as we sort it out, one problem at a time. Either from new gear, conditioning, and/or learning to ignore what isn’t perfect, we find out what works for us in the bigger picture. As long as we’re willing to put in the miles. Today, I was in the granny club with her, walking half my normal speed.

I got back on the trail, happy to have a calm sunny morning. The wind was backing off and the waves were smaller, glowing in the sunlight as it was breaking over the trees. Over the day, I passed bigger drive-in campsites as I approached Au Sable Point. At the top, the Au Sable Light Station looked over the water. It was built almost 150 years ago to alert ships of its presence at Au Sable Point, a notorious cliff point and sandstone reef. Without the light signal, ships would easily hit the shallow rocks extending into the water.

The trail continued in the trees with a bit of gain approaching Log Slide Overlook. My calves were improving, with greater range of motion and less pain. Finally, they were breaking in and starting to listen to me. Which would have been good, except now my feet were getting the same problem. The muscles around my heels especially were acting up. The good news was that the thru-hike was almost over, so it didn’t really matter.

I reached the Grand Sable Dunes, which follow the coast for five miles before reaching the town of Grand Marias. At one time, logging companies used the dunes to roll their timbers down to the water and float them over to the town. Now, this area is protected land and the trees aren’t going anywhere.

A short hike brought me to the Masse Homestead, a secluded campsite on the backside of the dunes. I needed to catch a shuttle on time at the end trailhead the next day, so I slept under the stars to save packup time. It wasn’t comfortable, but it got me out sooner. I packed up at 5am and hiked the first hour with a flashlight. The trail crossed the road, where I turned for a straighter walk to the visitor center. It was time to take the shuttle back to town and look for pizza.

I reached the end with 90 minutes to spare as I waited for the shuttle. While I waited, I boiled water and made coffee. Just to relax. I recalled the last few days of my hike with the ranger, who was setting up a display area in front of the main building. She pointed me to an apple tree across the road. And so, my trip ended with me eating victory apples in the visitor center parking lot.

In Memory of Iohan

In Memory of Iohan

“I Iohan want to see the world. Follow a map to its edges, and keep going. Forgo the plans, trust my instincts. Let curiosity be my guide. I want to change hemispheres. Sleep with unfamiliar stars. And let the journey unfold before me.”

Iohan Gueorguiev was an adventurer. He captivated the minds of countless people as he traveled by bicycle and packraft across the Americas, documenting his amazing adventures on his YouTube channel in a video series titled See The World. Beginning in the ice roads of northern Canada in 2014, he spent months traversing the Yukon and Alaskan highways before making his way through the American national parks and continuing south through Mexico. After volcano hopping in the Central American jungles and taking a paddling detour around the Darien Gap, he finally reached the shores of Colombia, all while filming and uploading his footage for us to enjoy. Years and countless stories later, he reached the high mountains of Patagonia at Lake O’Higgins before returning to Canada to work and wait through the pandemic.

And that was where his epic Pan-American adventure came to an abrupt and tragic end. The cycling community received a note from one of his touring friends in Argentina that he passed away about a month ago. That he suffered from chronic sleep apnea and insomnia, to the degree that he took his own life to end the pain. So many of us had come to love his videos over the years, and were shocked and saddened that this would happen to such a brilliant soul. I’m still trying to process my own feelings as I write these words.

I followed Iohan for years. He was one of the first people to truly inspire me to go on my own adventures and capture the experiences in video and written word. He had a purity to him that I always admired. His sense of adventure was simple, and genuine. Whether making friends with stray dogs, staying with host families in remote villages, or shooting an epic panorama, he was always able to capture the moment and tell a story that connects and resonates with us.

And so as I go through his old videos, so many things come back to memory. Like the Athabascan woman who sang about Denali in her native tongue. Or when he crossed paths with Sarah Outen on the Alcan Highway. And then camped on a volcano high above Guadalajara. And the time he tried to ride the back roads in Panama, only to see them turn into a mudslide and force him to hitch a ride out in somebody’s truck. And of course there were the incredible panoramas of the remote Bolivian highlands. To the soundtrack of Spanish folk music, Iohan was riding on the bottom of the screen, trying to fit the huge landscapes of the Andes into the picture.

And he was always meeting kind folks and animals along the road. He was a friend among many horses, dogs, cats, alpacas, and townsfolk. And yet, always moving on. Because he wanted to see the world. He wanted to follow the map to its edges and keep going. He wanted to let the journey unfold before him. And then he wanted to share it with us.

It’s impossible to say how many of us have been impacted and inspired by his journey – one so suddenly brought to an end. It never seems fair to see life taken away from someone who lived it to its fullest. But this is a story that will live on. As I speak, a group of his friends are planning a memorial in Ushuaia. I want to see it one day and thank him for sharing his life adventure.

He is Iohan, the Bike Wanderer. And while he may no longer be with us, our hearts are with him in the wilds of Patagonia.

Piers Gorge on the Menominee

Rafting Piers Gorge on the Menominee

I made a stop on my way back home from Michigan to do a quick trip on the Menominee River. The Piers Gorge rapids are the biggest in the midwest, most notably the Class III-IV drop at Misicot Falls. True North Outpost and a couple other outfitters bring people to run the canyon throughout the warm season.

The trip consisted of two laps in the gorge. We started upstream and towed another raft behind us while the guide taught us the paddling moves and safety orientation. Soon, we approached the falls. It consists of a river-wide ledge with a big tongue on the right side that washes down a 10 foot slide. It’s pretty much the line to use, although they said that other lines open up at higher flows. The tail waves were big and nearly tossed me out of my seat as they thrashed the boat to the left. The guide steered us downstream, avoiding Volkswagen Rock. Though easily avoided, it is a source of boat pinnings and one fatality about ten years ago. We continued on through the Sisters, two Class III wave/holes close to the end. Then we shored in and hiked back upstream to run the gorge a second time.

The second run was a bit smoother going over the falls without any surprises. For the heck of it, the guide turned us around and had us float the Sisters backwards. As I speak, she and her fellow guides are on their way to Gauley Fest. It will be her first time, and I have full confidence that she is well prepared.

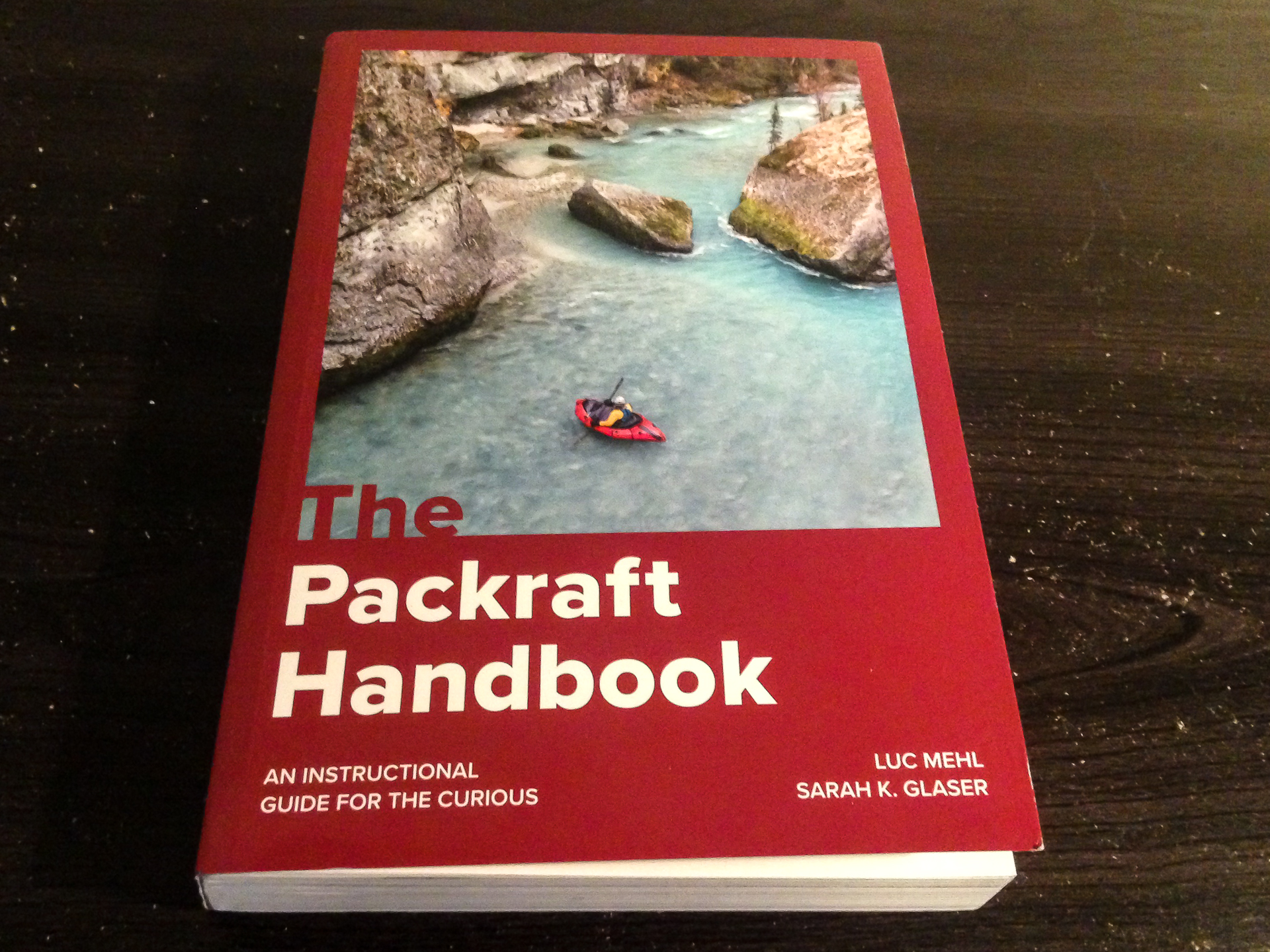

The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl

The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl

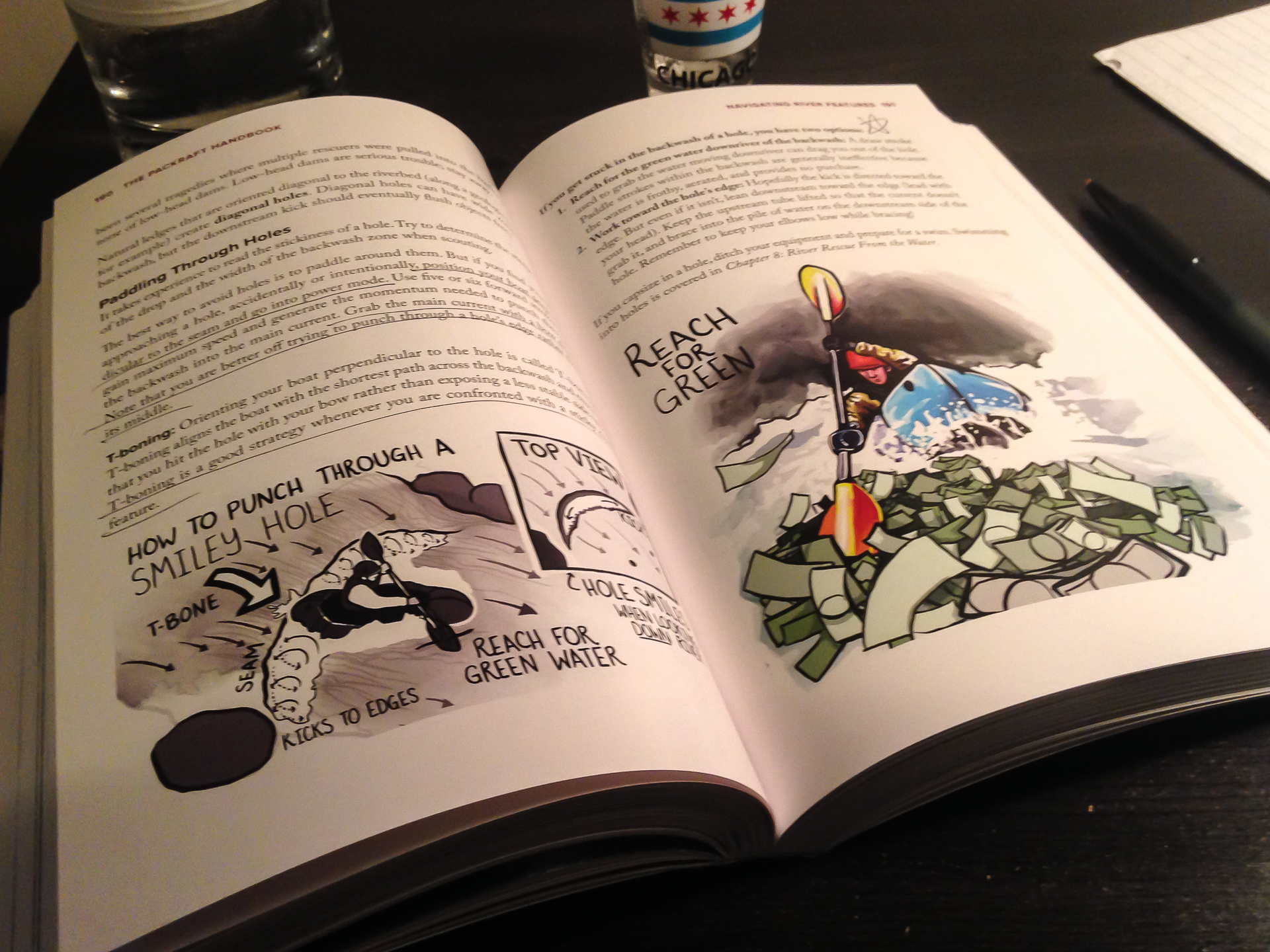

Over the last few years, the sport of packrafting has grown from a small community mostly consisting of backpackers in Alaska and Tasmania to people from all over the world – potentially anywhere that you can find runnable rivers that are accessible by foot. In more recent seasons, my feed has exploded with river footage from all across the US, Central America, Russia, Austria, New Zealand, Lapland, Scotland, Japan, and on and on. Which in one sense is great to see so many new people discovering what packrafting has to offer. But as the community continues to grow, so does the likelihood of mistakes, injuries, and fatalities. To date, there are twelve fatal accidents recorded that relate to packrafting.

In response to this increasingly important issue, Alaskan boater Luc Mehl published the Packraft Handbook in June of 2021, which is a comprehensive guide to amphibious river running. With the help of illustrator Sarah Glaser, this book provides a very detailed yet simple guide to everything a boater needs to learn – from preparation, to paddling technique, to capsize recovery, and swiftwater rescue. Which I feel is long due in this community. Because while packrafts are generally very stable and forgiving as watercraft, they have given many boaters – myself included – a false sense of security to run bigger rivers where we had no business going without proper training.

It was Luc’s goal to change that trend with this book. By adapting many of the river rescue techniques already developed in the kayaking community to that of packrafts, the book encourages a #cultureofsafety as its core ethos – a community where we can continuously educate ourselves and others on the importance of river safety.

The book is divided into four parts, the first being Foundations. Here, Luc describes the types of packrafts available, equipment, boat control techniques, wet entry, and risk assessment. New packrafters especially will benefit from the knowledge it offers on how to get started.

The second section, Rivers and Open Water, explains the basics of navigating different types of rivers and open water crossings. There are different types of paddling environments with risks inherent to each. Technical swiftwater is different from a windy fjord crossing, but both can be dangerous. It is important to be experienced and prepared.

In the third section, When Things Go Wrong, Luc describes many different types of accidents and the proper rescue response to each, detailing things like self-rescue, throw ropes, entrapment, rolling a packraft, equipment repair, and various examples of First Response emergency treatment that hopefully won’t be needed. I think this section is truly the meat of what we need to understand out there.

And finally, Part 4: Putting the “Pack” in Packrafting has two chapters about planning and logistics. Because it is easy to overpack when you already have to carry ten pounds of river gear. But at the same time, you don’t want to cut too many corners and underpack supplies that you might need, like say, a first aid kit.

It makes me wish I had thought about this four years ago when I made the mistake of running a scary glacial river in Iceland. It was a mile-long river connecting two lakes close to the Jökulsárlón Lagoon in the south coast, and appeared friendly on the satellite. I crossed the first lake and started down the mouth of the river, which was swift but calm. Before I realized it, the current started picking up into a Class II section and I was flying down a center line. Suddenly, I was seconds away from dropping over a river-wide pourover ledge of four feet. And a big hydraulic. With no time to find the line, I charged at it unsuccessfully and got tossed out.

And then I froze. Not literally, but mentally. For about two minutes. Flying down a river.

I thought I could kick my way to an eddy, but the current was too strong. Another rapid was approaching. I snapped out of the fog, threw the paddle across my boat, and lunged forward. I climbed back in and regained control, navigating the breaking waves. Ten seconds after I recovered, I went flying past what might have been a pinning rock.

I had originally planned to run another Class II-III river the next day, but realized as I got to shore that I needed proper rescue training and other partners before attempting something like that again. It could have ended differently. I could have died.

I could have died.

The good news is this this book can give you answers wherever you’re at with your skill level. In my case, I needed more practice at wet exit and recovery. A lot more practice. To the point that it becomes second nature to fall out, flip the boat, and jump back in. I also needed to recognize a wild river when I see one from the satellite. And most importantly, to never go alone on a river like that again. To quote my friend Ben on a similar note, “I lived and I learned.”

Since that trip, I have only done solo trips on easier Class I-II rivers in the Midwest and east coast, usually at the end of the summer when the levels are low. Appalachian rivers like the Shenandoah are nearly all pool-drop flows, allowing for easier recovery between the rapids. And many of them are commercially run, meaning that outfitters are already proactively clearing them of strainers and debris, for pretty obvious reasons. But still, I remind myself that paddling solo will always make me inherently more vulnerable to accidents, and that I need to be extremely cautious. Also, I won’t be running the Gauley in my raft.

But most importantly, I’m due for a swiftwater rescue course – for the benefit of myself and others.

In scuba diving, they teach us that the primary objective of any dive is always to get everybody back safe and unhurt. This is my primary goal of any river trip – for myself and the others to get through it safely. The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl explains how. From novice to veteran, boaters of all skill levels can benefit from the knowledge that it offers. So let’s make the #cultureofsafety a worthwhile goal this paddling season.

https://thingstolucat.com/packrafthandbook/

https://swiftwatersafetyinstitute.com/ssi-courses/