The Alpenglow of Denali

The Alpenglow of Denali

“To the lover of wilderness, Alaska is one of the most wonderful countries in the world.” – John Muir

This was it. Denali, the park that changed my life forever. I obsessed over Alaska for four years because of that incredible mountain. I saw it for the first time in 2012, two days after the summer solstice. I remember cycling on the park road all night under the twilight of the Alaskan summer, easily the most backbreaking ride I’ve ever done. I climbed over hill after hill, hours beyond my threshold of exhaustion. I was getting schooled on what it is like to go beyond wherever your limits are, only to find out that you’re not even close to your goal. Finally, I cleared one last big hill to the first overlook, and saw Denali thundering into the morning sky, five times as high as I remembered in my dreams. It shattered my whole world. But little did I know that it would make me into what I am today: A traveler.

Since that trip, I have traveled as often as possible by train, foot, bicycle, or raft. And I’ve seen a lot of amazing places. But nearly every day for years, Alaska was on my mind. It was time to come back and finish what I started.

The first place to go on my trip back was Wonder Lake, a scenic area at Mile 85 of the park road. It is about twenty miles further than where I ended my trip last time. I originally planned to see it then, but was way too fucking exhausted to go any further than the Eielson center that day.

I boarded a Denali-bound train from Anchorage on a cloudy Saturday morning, got to the park in the afternoon, and camped at Riley Creek, a large campground by the welcome center. Early the next morning, I loaded my bike and gear on a shuttle bus for the Wonder Lake Campground, where I planned to spend up to a week waiting out the clouds, which more often than not will cover over the mountains. But if luck will have it, the mountains will eventually clear, giving me the pictures I had hoped to get four years ago. The north face of Denali and the majesty of the Alaska Range above a large open plain of forests, lakes, and rivers. This time I would get it – this time with better gear and experience.

The shuttle was full of backpackers who planned for days or weeks of hiking in the backcountry. As the bus went along the turns of the outer range, sheets of clouds and rain bombarded the mountains, clearing just long enough to reveal a fresh dusting on the high ridges. Occasionally, the driver stopped to point out moose our caribou walking through the tundra fields. I hadn’t yet adapted to the time change, and my caffeine addiction was killing me.

After a few hours, the rain backed off to occasional breaks of sun between the dark clouds. We got to the Wonder Lake Campground in the early afternoon, which sits on a hillside of tundra facing the Alaska Range, 20 miles to the south. I managed to find a campsite and set up about an hour before the next shower. From there, I waited out the bad weather for better fortune.

I hiked for a few hours on the McKinley River Bar Trail to the edge of the McKinley, a huge braided river that flows out from the north side of the range. The trail starts through about a mile of tundra, stream crossings, and kettle ponds before going through a dense taiga forest, and then stopping abruptly at a rushing channel of the river. From here, people who want to hike the further reaches of the backcountry will scout out the McKinley’s elaborate braid system and ford the shallowest channels they can find. Instead, I went back.

Later that evening, a ranger gave a presentation at the small amphitheater next to the campground. The life of a park ranger in Denali. He summarized the history of the NPS and the park, and told us what it was like to live out there every summer. Behind him, the evening sun lit up the forests under dark summer clouds, which still blocked the high mountains. That night, I slept under scattered showers.

I finally got my break the next morning. The clouds started clearing up, revealing the curves of Wickersham Wall against the blue sky. Soon, Denali and the sister mountains were in the clear, standing high above the countryside in resounding glory. The evening sun descended slowly in the north, casting alpenglow on the high mountains.

It was game time. I am going to timelapse the shit out of this. I got on my bike with my camera gear and rode a few miles out to Reflection Pond, a classic vantage point where many a famous picture of Denali has been taken and remembered. I set up my camera across the pond, programming the shutter to hit every 5 seconds as the orange glow of sunset left the mountain. Slowly, it blended from orange to pink, to lavender, to pastel blue, and then finally bright colors again in the early morning. All while a solitary duck swam around the pond. All while the park slept under the twilight of the summer night. All while my camera clicked away, burning, forever burning the landscape into memory.

At about 5, I took my camera to a hill next to Wonder Lake, another famous overlook a few miles away. By now, the Alaska Range was blazing in white under a crisp blue sky, and the park was waking up from one of the shortest nights of the year. The sun crested over the hills to my left, slowly casting light onto the trees ahead, while ripples of wind blurred the glassy lake below. This moment was every bit as glorious as I had hoped it to be. There’s not enough breath in a lifetime to fill that sky.

I loaded my bike on a shuttle bus a few hours later and rode 25 miles up the park road to Stony Hill. I spent the next few hours flying back out of the range and onto the open plain towards the campground, curving around the hills of the tundra fields. This was my favorite part of the park. While pretty much any mountain in that park could be its own postcard, the panorama here was by far the most dramatic. The outer range to the east, the Muldrow Glacier and Alaska Range to the south, and more kettle ponds and waterfowl than you could even begin to count. I was all out in it. It was so fucking awesome.

I got what I wanted. Finally, after all this trouble. Denali, the crown jewel of Alaska, in a rare moment of clarity. For the longest time, this was the holy grail of my whole traveling world. And I got it, finally, after four years of wanderlust. So when I got back to my campsite that afternoon, something unexpected happened. I wanted to leave.

How was that possible after everything I had put into this? I think some of it was definitely the fact that I felt like shit for lack of sleep. I was also starting to miss the comfort of showers, laundry, internet, red meat, and beer. I was getting sick of my backpacking food, and liked the mosquitoes even less.

But I think the bigger thing was that I felt like I saw everything that I came there to see. It was sort of like going to an art museum and eventually getting tired of looking at really cool art for two hours. Well, I guess I was tired of looking at Denali for hours and hours, as hard as that was to believe. Wonder Lake was every glorious thing that people had to say about it, but I was done. I took a bus back to the headquarters early the next morning and camped for the remaining days in the shade and comfort of Riley Creek. As soon as I got back, I went straight for the park restaurant for a burger of champions.

Riley Creek is a large campground in the shade of the forest, which was exactly what I wanted on a hot day like that one. That afternoon, I was in the middle of sorting out my gear when I heard a voice behind me: “Hey, you want to see a moose?” It was Allison, a woman from North Carolina who was visiting the park for a few days before a business trip to Anchorage. I agreed, and we quietly snuck 30 feet away from a female laying down in the trees. A minute later, its calf walked up to it, and they both wandered off. They continued to hang around the campsite for days, much to the curiosity and worry of the visitors, probably because the mother knew that predators tend not to be a problem at loud campgrounds. Moose are usually irritable and dangerous, but they seemed to know that the people around didn’t want to bother them.

Allison and I left early the next day to hike up to the Mount Healy overlook, which is a sharp 1700ft gain up the mountainside right next to the headquarters. It was a steep, exhausting climb up the face of the mountain and took hours. But we finally managed to scramble onto a bare, rocky outcropping and see a great view of the Nenana River Valley. To the right, the ridge system went on for 10 miles before it would slope downward to the Savage River. The very top of Denali could be seen above the mountains to the west, only a few hours before it would hide in the clouds again. The haze of wildfire smoke blew in from the valley to the east. Down below, the thin strip of the Parks Highway followed along the glimmering Nenana River.

We made our way back down the mountain, got lunch at the park restaurant, and Allison left on a tour shuttle bus to see the park road. I went back to camp. And for the first time in weeks, I did nothing.

The next day was our last one in the park, and we agreed on one last vitally important thing to see: The Sled Dog Demo.

These dogs are a very big part of the work that goes into maintaining the park. In the winter, rangers use them to access areas of the park where vehicles obviously can’t get to. They grow and train the dogs at the kennels close to the main headquarters and take them out on practice runs all summer long.

Three times each day, they have sled dog demonstrations, where a ranger comes out to tell large groups of visitors about the dogs and their history and use at the park. Then they bring out one of the sleds and have some of the dogs run a loop right in front of the audience. Whenever they do this, the dogs go completely nuts.

And finally, everybody goes over to the kennels to take pictures and pet the dogs. The rangers believe that socialization is a very important part of their training, and encourage tourists to visit and pet them. Cause after all, a social dog is a happy dog.

Allison and I agreed that it was a motherlode of cute. I mean look at those guys. They redefine badass. It was a good final note to end this chapter of our adventures. Soon, we boarded the southbound rail and shared a seat in one of the dome cars. Her exhaustion finally got the best of her and she passed out in the seat. I continued to watch the forests and mountains go by.

I got out at Talkeetna and she continued on her journey southward. The train rumbled and faded into the distance and all was quiet at the depot. I wasn’t done with Denali yet. I got on my bike and made for the hostel.

This story continues in the South Foothills.

Mendenhall Glacier Caves

One does not dispute the risks inherent to climbing glaciers, and I was well aware of that when I hiked on the Mendenhall last summer. Ice and gravity together at that magnitude is altogether treacherous, wild, and alluring. Which was exactly why I wanted to see it – namely for its ice caves.

Formed by meltwater along its edges, its cave tunnels draw many ambitious hikers each summer. Visitors like me, who want to see its magical blue, glowing ice walls and ceilings for ourselves. But it is no easy trip, and is not without its share of bangups – either from tourists who don’t know what they’re doing, or people who are just unlucky. I had no experience or gear needed for any of this, and signed up for a guided trek with Above and Beyond Alaska, one of two local outfitters who were licensed to take hikers out on that busted, immensely rewarding trip.

They picked me up from downtown that morning and brought me and four other people to the trailhead on the west end of Mendenhall Lake twenty minutes later. We geared up for a long day of hiking, starting on the West Glacier Trail around 10:00.

Thick, mossy woodlands of Alaska’s Tongass National Forest enveloped us as our guide Cory led us along the lakeside. It was a dense, temperate rainforest – a faerie land of Sitka spruce, alder, willow, and an occasional break of sun through the canopy. A steep ridge lay between us and the glacier. The trail wound up the side of it in numerous switchbacks. We ascended for a while, still over our heads in wild overgrowth.

After an hour of hard climbing, we reached an open area of moraine and rock near the ridge’s summit, where only the toughest, scraggly flora can take root and grow. Soon, we were scrambling up the final edge of the climb, careful not to slip and tumble backwards. Some animals lock horns in places like this, I thought.

We made it to the top and looked out at the panorama that has made the Mendenhall famous. Huge, steep mountains surrounded the glacier and the lake below as it reached across the valley for three miles before flowing into the river. Tiny profiles of kayakers could be seen across the lake, 1,000 yards away. Above them, Nugget Creek glimmered against the mountains like a silver ribbon. The immense hull of the glacier in front of us had a huge labyrinth of blue and white spires that looked like the scales of a sleeping ice dragon of terrible power.

We ascended down the trail towards the west end of the glacier’s terminus. The earth was loose with gravel, no doubt at one time ground up and washed out from higher up. We barely had a trail to walk on, as the slope was almost entirely scree and loose dirt. It was exhausting and we weren’t even on the glacier yet.

We got to the edge of the ice and took out our climbing gear. Cory packed each of us with crampons, a harness, an ice axe, and a helmet. Once we were all fitted, we stepped onto the ice and started walking along the glacier’s surface.

It was smooth at first, but became increasingly uneven and intimidating. Its spires seemed to tower above us as we approached the crevasses further up.

All at once, my head started throbbing. As a coffee addict, I knew what it was right away. Nothing I could do about that now.

The ground got even more erratic, as Cory had us climb up small, icy walls, peer into crevasses, step over meltwater streams. In the picture above, I can be seen looking warily into a crevasse. And this one is small by all standards.

We hiked back out to the ridge and went a few hundred feet up to one of the more recent caves along the glacier’s edge. Originally a much bigger cave existed, but it finally collapsed last year. Fortunately, the glacier’s tunnel system is dynamic and changing all the time. This cave, a much smaller one, was just big enough for people to crawl in and take pictures, which plenty of tourists – myself included – were doing.

Satisfied we got our moneys’ worth, we ate lunch, packed up, and hiked back up the ridge. I expected the hike back over that ridge to be just as hard as it was going in, and it didn’t disappoint. And my head was absolutely pounding by now. I want coffee, dammit!

Cory led us along a higher trail with more scrambling, jumping over rocks, one rappel down a boulder near the tree line, and then a 45 minute downhill walk to the shuttle. He dropped us off in downtown, where I went straight for the nearest coffeehouse like the addict that I am.

That was a tough hike, but nothing I couldn’t write off as training for what comes next. Onward to Canada!

This story continues in the Canadian Rockies

An Alaskan Brewery Tour

Whenever I visit a new city, I want to find out what the locals drink. In Juneau, Alaska, the best place to do this is the Alaskan Brewing Company. With seven year-round beers, rotating seasonals, and numerous small batches, they have established themselves as one of the state’s pioneers of microbrewing, opening their distribution all over the region, and eventually expanding to the Lower 48 West Coast and upper Midwest.

Local ingredients go into what they do, as their water is sourced from snowfield runoff from the Juneau Icefield above. Spruce tips from local Sitka trees are harvested regularly to flavor their Winter Ale. And their malts are smoked in locally cut alders, promising a taste of the Last Frontier in every glass.

They offer shuttle tours to their brewery every day, which was great timing for me because the weather happened to be terrible. They picked me up along with three other guys at their merch store in downtown and drove us to the brewery five miles away. It is part of a small industrial corridor nestled between huge, foggy mountains. You wouldn’t guess what it is if it weren’t for the brewing tanks looming over the building.

We went inside to a small taproom surrounded by glass walls, allowing us to see their brewhouse. Ted, a Juneau resident ever since its inception, walked behind the bar and started pouring flight samples for us while giving us the history of the brewery and its relationship with the town.

In short, it was founded by owners Marcy and Geoff Larson in 1986, when nothing like it existed in the Juneau Borough. Unable to convince investors that they had cost-effective enough of a model for such a remote location, they went to the locals for help, financing their startup capital by selling shares to the townspeople.

They started by hand-packaging their bottles and cases, but eventually upgraded their hardware to meet the wildly growing demand. As their business escalated, so did their need for innovation and efficiency.

Disposal became a big challenge for the brewery in such a remote location. While brewers in the Lower 48 can more easily sell their spent ingredients to local farmers to lower their costs, this wasn’t an option at their facility. To solve this, they became the first American brewery to employ a Mash Filter Press – a Belgian-patented machine that is used to force the water out of their spent grains. The water is then reused in the brewing process, and the newly dried grains are reused as fuel.

Furthermore, they figured out a way to harness and reuse their carbon emissions. Geoff, a chemist by trade, designed a CO2 Reclamation System, which captures the emissions caused by the yeast in fermentation, and then reuses it for packaging and purging oxygen from the holding tanks.

It is because of these sustainable, cost-effective innovations that they have managed to lower their production costs and remain present in an increasingly competitive industry. Fuck yeah!

After a truly great history lesson, Ted brought us to the tasting room, where a bartender gave us more samples to drink. The Alaskan Amber, their primary flagship ale, became my favorite as I visited the brewery and the town. It is characterized by a crisp, lightly bitter foretaste and smooth, refreshing, malty flavor, which they attribute to a slow fermentation process. Their award winning Oatmeal Stout was another good one, blending oats and malts with an edge of coffee and caramel.

And numerous other flavors of the rainbow can be had in their taprooms. Whatever I didn’t have enough of there, I found at the bars in downtown.

Their distribution goes as far as the upper Midwest, but hasn’t yet opened in Illinois. For now, I have to go to Milwaukee or Michigan to find a case of their Amber Ale. I know it will get here eventually. Ted told me that they’re working on it, and I’m sure he’s a man of his word.

Packrafting the Mendenhall River

Packrafting the Mendenhall River

I think I’ve found the partiest day trip: The Mendenhall River in Juneau, Alaska. It is an ideal combination of scenic flatwater paddling in view of majestic mountains, icebergs, and glaciers – with the adrenaline of hard-hitting Class III rapids downstream as the river makes its way to sea.

The lake and river are both in the Mendenhall Valley, which comprises of most of Juneau’s residents. By chance, I was able to catch a tourist shuttle from downtown to the park headquarters along the lake. A short walk from there brought me to the boat launch close to Nugget Falls, a big cascading waterfall that pours down the side of Thunder Mountain and onto the lake.

I blew up the raft, suited up, and paddled towards the waterfall, whose meltwater crashed and roared its way onto the lake’s surface. Up ahead, the blue ice of the Mendenhall Glacier rose above the horizon line, nestled between the hardened slopes of rock. Further above, higher, bigger mountains rose above the arm of the glacier. And somewhere above them, the open plain of the Juneau Icefield reached across for some 50 miles – one of many that exist throughout the Pacific Coastal Range, feeding rivers like the Mendenhall.

As I made my way north, the glacier slowly grew in size until it was a massive blue wall of three stories that spanned shore to shore for 2,000 feet. All was quiet, but my head was racing. This place was fucking awesome.

Should I get any closer? I debated it, but I didn’t know very much about this glacier, or how stable the ice was at the edge. Sooner or later a calving was going to happen. And I wouldn’t want to be close to a house-sized block of ice if it fell off. So I stayed far enough away that it would have been a huge wake at the very worst.

I turned south and spent an hour paddling to the other side past icebergs, all while a more distinguished vista of the glacier and mountains above it became apparent. Before I even realized it, I was getting pulled into the mouth of the river and the onset of some Class I-II rapids, which were fair warmup for the bigger ones downstream.

Earlier that weekend, the glacier had what is called a jökulhlaup – an Icelandic term that describes a sudden break in glacial meltwater from the snowfield higher up. The water then rushes into the glacier’s moulin and eventually reaches the river, causing the levels to spike. It was definitely a few feet above normal, and had already flooded some of the surrounding trails around the lake. This isn’t altogether bad in bigwater like the Mendenhall, which just escalate into fun rollercoaster rapids.

After a few small, riffly sections, I came around a left bend and approached Back Loop Bridge and the start of Pinball Rapid, the big Class III of the day. Other boaters told me there really isn’t any one line through it, and I could pretty much navigate on the spot. So that’s what I did, fighting to keep my boat straight through a barrage of breaking waves. I remember seeing a huge hole to my right as I passed under the bridge and worked my way towards a big wave train on river left. It had more than its share of laterals, one of which almost flipped me.

Further down, the rapids settled as I passed a few surf holes and river bends. The last big rapid pulled me into a wave train on the right. I had to fight to stay clear of the flooded trees along the bank, the only potential hazard I noticed on the run. At the time I didn’t notice, but in the footage I got smacked pretty good by a lateral wave about halfway through.

There’s no better place to truly feel alive than in the middle of wild, crashing water.

To Andrew WK, partying is living. While the term “party” can be used as a noun or verb, it more importantly describes a feeling of ultimate Zen or Being. To me, the middle of a wild river is where I’m feeling my partiest.

I made it through without capsizing, and floated along calm flatwater for a few miles past back yards before taking out at a city trail and walking to the road.

I would recommend the Mendenhall to anybody looking for a fun day trip in the water. If you don’t have your own boat, local outfitters rent kayaks along the lake and offer guided raft trips down the river all summer long. From experience, I would say that either way you do it is very party.

What Should I Do In Alaska, Dan Hagen?

What Should I Do In Alaska, Dan Hagen?

Every now and then, somebody asks me for advice on what to check out in Alaska. First of all, plan on staying there for at least two weeks and make Anchorage your home base. This should give you enough time to spend a few days in Denali, a few in the Kenai Peninsula, and the Anchorage area in between. Also, go in late June during the Summer Solstice. Alaskan winters have their own set of options as well (auroras, cross country skiing, etc.), but I have no idea where the best places are for that.

Denali

Spend a few days in Denali National Park. Make this your main priority. Even if you blow off everything else, do not pass up the chance to see that mountain. Every other vista I saw up there pales in comparison. And the mountain isn’t the only thing to see in the park, there are in fact, six million acres of beautiful wilderness up there.

If you don’t feel like going all the way into the park, they have a good trail system around the welcome center. The Mt. Healy Overlook Trail offers a good day hike to the mountain’s summit, just above the headquarters. If the weather is clear, you can catch a glimpse of Denali’s summit, 80 miles southwest.

The park offers shuttle buses into the park’s interior, stopping at Wonder Lake, the best known place to see the Alaska Range. According to the park rangers, Mt. McKinley appears out of the clouds one in every three days. It’s a gamble as to whether or not you will see the mountain, unless you decide to camp at Wonder Lake for several days, which I plan to do when I go back.

Numerous other options exist for day hikes, multi-day backpacking expeditions, packrafting trips, cycling, so on. Rangers at the backcountry office can help you get an itinerary figured out if you’re looking to do something ambitious.

Not convinced yet? Check out this sweet Flyover Video.

Talkeetna

To the south, the town of Talkeetna is a great place, buzzing with backpackers and mountaineers in the summer. If you don’t have time for a big expedition in Denali, you can see a good view of the range from an overlook in Talkeetna. Two air taxi companies offer flightseeing tours, where they fly around the mountain and then land on one of its glaciers. So if it’s too cloudy to see the mountain from the ground, you might luck out and see it in flight. One of those tours costs about $400, but I’m sure it’s worth it.

The Kenai Peninsula

A two hour drive south of Anchorage will bring you to the Kenai Peninsula, which is loaded with things to do and see. The drive itself along the Turnagain Arm is beautiful. The highway winds along the north edge of the fjord with the view of the Kenai Mountains, five miles south across the water. Chances are pretty good that you’ll catch a glimpse of beluga whales, eagles, moose, and Dall sheep.

As a cyclist, the Bird to Gird Trail from Girdwood to Bird Point is one of the best bike paths I have ever seen. It winds along the mountains above the Turnagain Arm for thirteen miles. Rent a bicycle from the Girdwood Ski and Cyclery and check it out.

The port town of Seward sits along the side of Resurrection Bay, and offers many options for backpackers and tourists. Many people take glacier cruises out to the fjords to the west. Mountains, glaciers, fjords, and sea life are all abundant. Outfitters in the town rent out kayaks and offer trip packages if you’re the sort of person who would enjoy paddling across the bay and camping in solitude.

A short drive to the north will bring you to the Exit Glacier and the edge of the Kenai Fjords National Park. A day hike on the trails alongside the glacier is doable. If you’re up for the challenge, the Harding Icefield Trail will take you high up the side of the glacier and within eyeshot of the ice field where it begins.

The town of Homer, a three hour drive west of Seward, is another popular coastal town in the summer. It is known for the Homer Spit, a four mile strip of land that reaches into the Kachemak Bay with a stunning view of the mountains on the other side. Set up camp along the spit, and you won’t be disappointed. Options also exist here for kayak rentals, flightseeing, fishing, cabin rentals, and so on.

Anchorage

Anchorage has plenty of things to do. I enjoyed its hole in the wall taverns like Darwin’s Theory, Humpy’s, and Moose’s Tooth. The Glacier Brewhouse is a great restaurant and home brewery with a great selection of craft beer and locally caught salmon and halibut entrees.

The Downtown Bicycle Rental is a bike shop that rents bicycles out during the day. Take one and ride it around the city bike trails and forest parks. They are very well maintained and lots of fun. The shop also shuttles people up to the trailhead of Flattop Mountain just east of town, where you can take a short hike to the summit and see all of Anchorage, and maybe Denali if the weather is clear.

The Alaska Railroad depot is right in downtown and is a great option for trips to Seward, Whittier, Denali, Talkeetna, and Fairbanks if you don’t feel like driving. I took the one to Seward, and many of the train cars had upper decks with dome shaped windows on the ceiling, offering great panoramic views of the landscapes. An announcer describes the scenery as the train goes along, providing lots of interesting facts about the land.

The Glenn Highway is another great drive, going northeast of Anchorage through mountain ranges for a few hours. You’ll reach the Matanuska Glacier around mile 100, which can be seen from the highway. Numerous options are close by for campgrounds, cabin rentals and roadhouses.

The 142 Bus

Finally, if you’re thinking about visiting the Magic Bus on Stampede Road, my advice is this: Instead, go to the 49th State Brewery in Healy and get a cold beer and a picture in front of the prop bus they used for the movie. That’s why they have it there. I didn’t see the Stampede Road, but everything I have read about it seems to indicate that it is in a very boggy, mosquito infested, uneventful part of the park. That, and trying to ford the Teklanika River is dangerous at best. For all that trouble, I would just as soon put that time into exploring Denali.

If you are serious about it, do your homework and learn the basic backpacking skills, especially river traversal. My suggestion is to use a packraft, which has the packed size and weight of a tent. You can bring it to a big river, inflate it, paddle across, and then put it back in your backpack. Local outfitters in the area rent them out.

Really, if you’re going anywhere for more than just a day, make sure you’re prepared when it comes to backcountry skills, knowledge, and gear. Basic things like waterproof layers and boots, synthetic base layers like wool or polyester, bug spray, a GPS, bear safety, etc. The REI in Anchorage is a great place to find almost everything you need, and learn from experienced backpackers. Getting through the alpine wilderness isn’t rocket science, but it can be very unforgiving to people who aren’t prepared.

The fact is, Alaska is full of amazing places to see. This list only covers a few of them. You’ll know that soon enough, and you will want to go back. I guarantee it.

Read my story: Part 1: Cycling Denali Under the Midnight Sun

Last Minute Century on the Glenn Highway

Last Minute Century on the Glenn Highway

…continued from Part 1: Cycling Denali Under the Midnight Sun

It took me a couple days to feel like a normal person again. That trip really kicked my ass. But I was satisfied that I saw Denali on a good day. It was awesome, and it was done and over with. But I still had two more bike tours planned, the next one being a 104 mile ride northeast up the Glenn Highway to the Matanuska Glacier, a large glacier on the northern end of the Chugach range. The good weather had passed and it was back to rain and erratic, unpredictable weather patterns in the mountains. So I waited for another good window, and in the meantime, got familiar with the bars in downtown Anchorage.

I spent some time emailing women online, because I was curious to know where the good bars were in town.. Since I was visiting from out of town and had some extra free time between bike tours to check out the local scene. And because I was curious to see what else they like to do around town. And then maybe one or two other random questions about their profile, and maybe if they were up for the randomness of it, meet up for a drink at a classy local establishment.

On that note, I noticed that the drinkers up there were some rowdy people. I was out with a lady one night in downtown, and a local guy next to us explained to me that a lot of the local drinkers are energy workers in Alaska’s oil industry way up on the North Slope. They go up for two weeks at a time, work for 60 hours each week, and then fly back to their homes and take the next two weeks off, which they end up spending getting shit housed at the bars.

“Up here, we only care about four things,” he said.. “Eatin, drinkin, fightin, and fuckin!”

I came back from downtown the next night and noticed that the clouds had lifted off of the Chugach Mountains. I found my window. When it’s nice, I realized, now is as good of a time as any.

I got my gear together and left the hotel at 1:00am for a 104 mile ride northeast up the Glenn Highway. Hopefully I would get there by the next afternoon, camp at the Grandview Cafe, and come back to Anchorage the following day. 208 miles, two days. With cargo. The first one being mostly uphill and overnight. I had obviously learned nothing from my previous trip.

There was plenty of light outside to get me through the early morning. The glow of dusk was endless as I rode under the twilight in what felt like a morning that would never end. The midnight sun was just below the red horizon to the north and the mountains to the east carved dark green shapes into the sky.

After 30 miles, the road turned northward and passed through the Matanuska Valley. The sun would be up in an hour. Mist hovered above the ponds and marshes. Clouds hung above the mountains to the south. To the east, Lazy Mountain rose high above the town of Palmer, where I planned to stop and get breakfast.

Palmer was the last town on the highway that I knew of to get food before going into the mountains. After that, I could have found a roadhouse every 30 miles or so, but nothing I could rely on. I sat outside McDonalds for an hour and waited for them to open before realizing that a grocery store and Starbucks in the shopping center were open already. The lady at Starbucks told me that she goes with her family up the Glenn Highway every year and camps around Mile 85, a forested area near the pass with a number of lakes and back roads.

Just east of Palmer, Lazy Mountain stands 3500 feet above the valley. The Matanuska River comes out of the range and passes around it from the east. The highway goes alongside the river for the next sixty miles upstream until passing within eyeshot of the Matanuska Glacier. That was where I meant to go.

After passing through a heavily forested, uneventful part of the highway for 10 miles, I reached the river. Up ahead, the morning sun broke out of the clouds. I stopped at a lookout where the river braids across a gravel bar a half mile wide.

This river, like many in Alaska, is glacier-fed. Over time, glaciers move along their valleys, grinding the bedrock underneath into powder, which gets carried downstream by the melt. Whatever sediment isn’t carried out to sea ends up accumulating on the riverbed, causing the rivers to braid over large gravel bars. Backpackers often attempt to ford rivers like this by scouting out the smallest braids they can find. I’m nowhere near that ambitious. Not yet.

The valley narrowed and the highway followed closely by the river until it passed by King Mountain, a large solitary mountain that looked as if it stood out over the land for many ages. I remembered seeing it online when I scoped out that highway on Google. Too bad I didn’t think to scope out the rest of the highway, or I would have been more prepared for what was coming.

To my disappointment, the highway parted ways with the river and climbed steeply along the facing ridge, gaining a lot of elevation at very little distance. So this road did have some grades, and they were ugly. Shit. I wasted no time getting started and hit the first climb for twenty straight minutes.

It turned along the slopes of the Talkeetna Mountains, giving me plenty of scares whenever I looked over the guard rails. I was inches away from one wrong move, which could send me tumbling over rock slides for hundreds of feet. I turned back and saw a great view of King Mountain rising high above the river and forest to the west.

Out ahead, the highway continued to climb, occasionally giving way to a downhill coast to a stream, and then winding even further upward. I did nothing but climb for the next hour, hoping that I would come around a turn and see the road level out, only to see it go further upward.

Somewhere in the middle of this, I passed a lady named Renee, who was on a tour from Anchorage to Los Angeles. It was her second day in. She spent the last night in Palmer, planned to get over the range, and continue towards Glennallen in the east. After talking I bit, I passed by, pushing hard into the next mountain grade. She had more cargo and was pacing slowly for the long term, and obviously intended on saving her strength. Instead of say, leaving in the middle of the night for two centuries back to back.

At this point, the top of the pass was five miles ahead. To my right, the mountain slopes curved down to the edge of a gorge, where at the bottom, the Matanuska was raging in the late morning sun. Lakes were everywhere along the slopes, drawing local people far and wide to come out in trucks, RVs, and fishing gear.

I finally made it to the top of the pass around noon, and the valley opened up ahead. To the south, the Matanuska Glacier reached far across the valley, carrying ice and rock from the high places of the Chugach range, where it turned upward for another twenty miles. Headwaters braided out from the glacier, forming the river, and carving into the ravine downstream.

Lion’s Head, a small, horn shaped mountain, stood on the north end of the valley. It was the remains of an ancient volcano that had been scraped away by glaciers long ago. After millions of years of friction, it was all that remained of a prehistoric mountain in the alpine country. And still, this place was as wild as ever.

The fatigue finally caught up with me at mile 100. I crested the high end of the pass, and hoped to get 9 miles of mostly downhill, where I would set up camp at the cafe, get some coffee and red meat, take a long nap in my tent, relax and enjoy the rest of the afternoon.. oh shit. I came around a turn and looked in horror as the road went downhill at a 7% grade for almost a mile to the bottom of a canyon, then crossed a bridge and went back up the other side at 8%.

Already exhausted from riding all night, and with only four miles to the campground, shelter, and hot food, I had to haul my cargo up a fucking mile of hard uphill. Dammit.

Bitterly, I coasted down to Caribou Creek and started a long climb up the other side. A climb like this in the early morning is one thing, but I had already been on the road twelve hours. I fought my way up the other side, inch by inch, swearing and taking breaks every few minutes. It made no difference.

The road finally leveled out, and I descended to the cafe where I got the best Philly Cheesesteak of my life. I’m pretty sure my chest hair increased by 8% that day.

The Grand View Cafe is on mile 109 of the highway, on the eastern slopes of the range. It has a restaurant, RV park, tent sites, families, dogs, campfires, and short hiking trails out to the river. When I got there, I set up my tent, locked my bike, ate a rewarding lunch, and took a nap until the late afternoon.

I got back out and saw Renee setting up camp at the site next to mine. She planned to keep going east to the town of Glennallen the next day, another 75 miles of mostly gradual descent from the range, then make her way out of the state and into Canada after that. For this trip, I would be turning the opposite way, riding 104 miles back to my hotel in Anchorage.

Next time I want to keep going east. The highway descends out of the mountains and levels gradually into a large plain of lakes, tundra, and spruce forests before reaching Glennallen, the Copper River, and the edge of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. From there, you can see the St. Elias Mountains, some of whom soar higher than 15,000 feet. The Copper River flows along the edge of the plain, and is famous for its salmon, who migrate upstream to their spawning grounds every summer by the millions. People and bears alike wait for them in the river, easily catching more than they can ever eat. I would love nothing more than to get out there, wait by the water, and eat one right out of the river like a fucking caveman.

A family in an RV saw me with my bike and gear, covered in a night’s worth of dirt and sweat, and wanted to know where I was headed. Then they offered me some of their campfire hot dogs and homemade wheat beer. I’m never one to turn away good road magic, and took them up on it.

Isolated rainclouds came in from the east and ran me back into my tent, where I slept like a rock.

My phone alarm went off early the next morning and I didn’t want to get up. I’m pretty hit or miss when it comes to camping. Either I’m asleep peacefully, or I’m tossing and turning, waking up every 45 minutes. Thanks to the workout I got the day before, and the light drizzle of rain on the tent ceiling, I had a calm, uninterrupted sleep all night.

I packed up, got a quick breakfast, and turned west on the Glenn Highway, dreading every second that I would have to climb the far end of the 7% grade at Caribou Creek. It was the same distance as the day before, just a notch lower in difficulty. Instead of climbing 8 feet, I would only climb 7 for every 100 in distance.

I descended down the facing grade, crossed the bridge, and got moving at a good pace as soon as it got to 7%. Ten minutes later, I got to the top, surprised at how much better I felt. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it was easy, but it was, I would say after a good night’s rest, doable. It turned towards a short descent, another steep climb, and then mostly downhill for a while.

Every awful climb I endured the day before was in my favor now, and my cargo weight made me go even faster. I was on the side away from the guard rails, my confidence was at an all-time high, and I had no problem shifting into high gears, flying down the grades, following the Matanuska for 60 awesome miles all the way out to Palmer.

I got there in the early afternoon, coasted down a big hill, and made the mistake of getting dinner at McDonalds. A man standing in line recognized me from the campground, reminding me of how small the world is in a big state like Alaska.

I was just about at sea level when I left Palmer, turning south at the junction towards Anchorage. It might as well have been uphill with the headwind I was getting. That, and to the traveling cyclist, a McDonalds combo is the equivalent of adding ten pounds of rocks to your cargo. The last 40 miles back were uneventful, and I had to deal with the added punishment of two centuries worth of riding and a full stomach’s worth of bricks to burn off over the next few hours.

I got to my hotel at 6:00 that evening and fell asleep without bothering to eat or take a shower.

I had two bike tours behind me now. Both of them kicked ass. Both of them were brutal. And both of them were unbelievably rewarding. Would my last ride on the Seward Highway bring its share of challenges and blow my mind like the first two did? Probably. Would I have a bigger, fuller beard after it’s all said and done? Absolutely.

Downpour on the Kenai Peninsula

Downpour on the Kenai Peninsula

…continued from Part 2: Last Minute Century on Alaska’s Glenn Highway

I had just over a week left in Anchorage and was starting to get tired of the place. I had seen everything that was interesting about the city, and was at the point where it was time to either stay and make new friends, or move on. Nonetheless, I had one bike trip left that I wanted to do before leaving: A two day tour up the Kenai Peninsula from Seward to Anchorage.

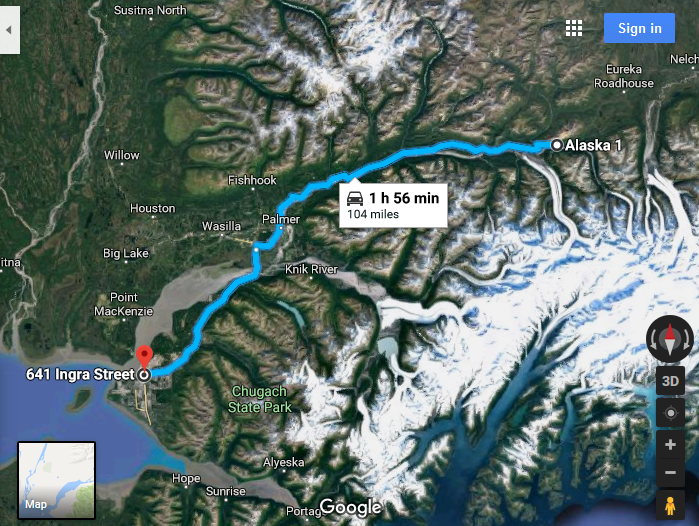

From Anchorage, the Seward Highway goes south for 128 miles, passing southeast along the shores of the Turnagain Arm for the first half of the drive, and then going south through the Kenai Mountains for the other half, and stopping in the port town of Seward. The Alaska Railroad has a line that goes straight there from Anchorage early in the mornings. My plan was to take my bike down there on the train and spend the next two days cycling back up the highway.

The problem was that almost every single day had rain in the forecast, and I really didn’t feel like riding on cold, wet roads. That, and I was hoping for a good sunny break like I got up in Denali. As I’ve said already, Alaska is beautiful regardless, but only during clear sunny weather do you get to enjoy the scenery to its fullest.

Unfortunately, in the summer, coastal Alaska tends to be cloudy and rainy just about all the time. So I waited a few days, spent some time on short day rides in the forest parks around Anchorage, got work done in my hotel room, screwed around and wasted time.

I went up to the trailhead of Flattop Mountain one afternoon on my bike. It stands right at the edge of the Chugach Mountains east of town, and is a popular day hike spot for the locals. What I didn’t realize was how steep the climb was to get up there, and was actually pretty well beat up by the time I reached the parking lot by the trailhead. The mountain was covered in clouds, so climbing to the summit just to look at fog seemed kind of pointless. I got a few pictures of the valleys around and went back down to Anchorage.

I finally got my train ticket to Seward a day or two later. There was a 30% chance of rain in the forecast, but with three days to spare before flying home, it was now or never. I rode to the station early the next morning, checked in my bike, and boarded the train.

To say the least, the Alaska Railroad was impressive enough for me to recommend to any visitor. Many of the train cars had upper decks with glass dome ceilings, allowing tourists to sit and view one breathtaking panorama after another. As soon as the train started, people scurried to the upper decks to get good seats for the ride southeast. Knowing that I was going to see all the same places the next day on my bike anyway, I didn’t bother to join.

We went southeast along the Turnagain Arm, a large inlet that flows between the Kenai Peninsula and the Chugach Range. The Kenai Mountains and the remote town of Hope, Alaska stood five miles to the south across the water. Five miles as the eagle flies, and ninety if you want to drive there. Up ahead, the morning sun broke out of the clouds, casting gold onto the water. The announcer pointed out some dall sheep high on a ridge to the left.

I got breakfast in the dining car and slept for an hour. I woke up and noticed that we were already somewhere in the Kenai Range, parting ways with the Seward Highway and climbing up over the next mountain pass to the east. The forests in this part of the state were darker, denser, more lush and enchanting, and were part of a temperate rainforest that spans from that area to the southeast and down Alaska’s panhandle. In this climate, conifers can grow for longer seasons than those of the boreal forests throughout Alaska’s interior. I looked out at the land, and clouds hung low over the valleys, reminding me of the woodlands of the Pacific Northwest. It was a dreary, charming landscape.

We went along a cliff, through a tunnel, past a waterfall, and stopped on the announcer’s word along the facing ridge of Spencer Glacier, whose blue ice had carved a steep, mile wide valley into the earth.

The train rejoined the highway, where I planned to ride that day, and made its final descent through the dense forests to the depot in Seward.

Seward is a beautiful place. A small fishing town along the rugged coastline of the Kenai Peninsula, it sits on the western side of Resurrection Bay, which flows south between mountains and islands for twelve miles before reaching the open ocean. To the east and west, there is nothing for hundreds of miles but a rugged glacial coastline and an occasional fishing town or village. Directly west, the Kenai Fjords National Park draws tourists and backpackers, many of whom come down on the train from the north and ride commercial cruises within eye shot of the glaciers and sea life. The more ambitious people traverse the fjords with kayaks or packrafts. And if you take a boat and fishing gear out to sea, you can catch more salmon and halibut than you will ever know what to do with.

To say the least, I regret my decision not to stay there longer. I made time for a quick stop at the Resurrect Art Coffee House, a cute little place in downtown, chatted with the barista, fueled up on some pastries, and got started on a 68 mile ride north through the Kenai Mountains. I passed the marina on my way out, catching a good scent of a recent catch from a town fishery. Fuck, I have to come back here.

I was 30 miles into the mountains. They seemed to close in around me. And yet, every uphill climb I did on that highway was a breeze. Nothing like the grades I fought on the Glenn Highway, or the ones at Denali that made me almost give up and turn back. I crested one easy hill after another, following rivers through the steep, narrow valleys and cooling off under an occasional drizzle.

Halfway through the day, I stopped at Summit Lake Lodge and got a hot meal. The owner told me that it was the highest point in the range, and that everything afterward was at a downhill descent all the way to Turnagain Arm and the edge of the ocean.

I stopped an hour later at a ravine to get some pictures, and noticed a large bird gliding a hundred feet right above my head. When I looked again, I realized it had a white head. Holy shit, that’s an eagle! It turned and flew out over the gorge, catching an air current and flying upward in long, slow circles until I could barely see it anymore. I got back on my bike and made for Turnagain Pass, twenty odd miles ahead, and planned to camp that night.

Each of my three bike trips in Alaska had their set of challenges. In Denali, it was the 10 mile climb up Sable Pass with heavy cargo (especially that fucking bear canister), the clouds of mosquitoes, and sleep deprivation induced delirium. On the Glenn Highway, it was the fact that I had to climb an 8% grade after biking for more than 100 miles overnight. On this trip, it was the wall of rain that hit me in the face when I came around the turn at the bottom of Turnagain Pass.

In no time at all, I was drenched. I hadn’t done my homework and bought waterproof gear or eye protection. As the downpour hit me in the eyes, I picked up the speed to get to my camping spot, where I could hopefully set up a shelter and dry off.

I reached the rest stop on the highway, found the large hill to the west, and looked for an easy way to get to the far side and set up my tent. I needed to hurry the hell up, it was getting cold and the rain wasn’t stopping. I found a game trail that led out to the side of the hill, crossed a creek, pushed through a bramble of willows, found a level spot away from eye shot of the highway, set up my tent, and got my ass inside.

It rained all night. I don’t know if it was condensation building up on the tent walls, or a leak somewhere, or both, but water kept accumulating on the corners. It was a cheap $40 Wal-Mart tent that just big enough for a cub scout, and as far as I am concerned, was a piece of shit. I spent two hours mopping water from the tent floor before I finally decided to just sleep through it. If it wakes me up, so be it.

My sleeping bag ended up saving my ass. I woke up and noticed that it had gotten lighter outside. It was 6am. I had slept for four hours. Good enough.

The downpour stopped. Outside, the landscape lightened and a break of sun came out on one of the mountains. It wouldn’t stay that way for long. The rain was hitting the tent in rounds all night, about one every 30 minutes, so I knew I had to get moving.

I packed up, hiked back to the rest stop, and got my gear together in one of the outhouses. I got my tent out and threw that piece of shit in the trash, drank a reserve bottle of water, and had a bag of beef jerky for breakfast, freeing a good ten pounds from my cargo.

As soon as I got back on the road, another downpour hit me head on. In that early hour, I could feel the cold right away in my fingers and toes, which started to go numb after twenty minutes. I supposed it’s to be expected if you’re using fingerless gloves and cotton socks, yet another backpacking lesson learned the hard way.

I came down the pass to the edge of the inlet shoreline, an absolutely stunning vista of panoramic scenery, with tall, breathtaking mountains to the north, south, and east, but I was too groggy, hungry, cold, and pissed off at the weather to give a shit. The highway turned southeast, crossed the rivers that emptied into the Turnagain Arm, and then went northeast along the shore for 40 miles all the way back to Anchorage. Fog hovered around the tops of the mountains, and the valleys between them were dark and grey, taking in one downpour after another. More cold rain hit me as I traveled east. When is this shit going to stop???

I was 20 miles from Girdwood, a ski resort town along the highway. I planned to find a roadhouse or diner there and get some much needed shelter, hot food, and most importantly, coffee. When I arrived, I found a shopping center right by the highway with a family restaurant.

I tried to lock my bike and the key to my U-lock stopped half way. Fuck. Weather and dirt must have worn it down, rendering the thing useless. Could be worse; at least it didn’t happen after locking it. Then I would have had to bust it off with a car jack or blowtorch, and maybe convince a few people that I’m not trying to steal my own bike.

I parked it next to the front door of a coffeehouse and went inside for some coffee and pastries. I got in line behind a group of cute hippie girls, one of whom had done some touring herself. Apparently, it was supposed to be nice that day and a festival was going on in the town. They told me I should come along. If I hadn’t already made plans in Anchorage that night, I would have taken them up on it.

I rode a few streets into the town and found the trailhead to the Bird to Gird Trail, an awesome bike path that goes along the ridges above the highway for 13 miles. Up ahead, clouds broke up where the fjord met the ocean, giving way to a bright blue sky.

A warm, dry, powerful tailwind hit me from behind, sunlight broke on the bigger mountains, and just ahead, another eagle flew above a spruce forest along the slopes. They are abundant in the boreal country, especially along the mountainous shorelines, where perch sites are plentiful and views of the water are far and wide.

The trail climbed uphill a few hundred feet and then descended back to the shore, ending at Bird Point, a bird sanctuary where you can walk up to a platform and watch eagles in their habitat. I didn’t see any, and figured they were out catching their food from the water.

I got back on the highway, the sun was finally out, and an even more powerful tailwind pushed me along. I barely even had to pedal. It was great severance pay for all the shit that I had endured the night before. Alaska’s climate, unpredictable though it may be, can sometimes work in your favor. Cyclists passed me going the other way, fighting the same wind current that I was enjoying. Watching them do that was an added bonus.

I got to Anchorage an hour later, and saw yet another eagle gliding into the air currents high above the marshy shoreline. My hotel was near downtown, another 7 miles north through the city. I just about coasted the rest of the way. I did it. I got to Alaska, I saw more unbelievable things that I could ever remember, and I toured what are without a doubt some of the best highways in America. What I saw and did in this countryside would stay with me forever.

I had met a lady named Ana the week before, who was living in Anchorage for the summer and working at a hot dog stand in downtown. I thought it would be funny to give her a surprise visit. So my trip ended as I sat next to her hot dog stand at one of the city parks, eating reindeer sausage and restoring my body of same badly depleted calories and protein.

Two days later, I was on an overnight flight back to Chicago.

It has been a year and a half since I made that trip. And I’ll be honest, there is not a single day that goes by that I don’t think about that wilderness. Even now, I scribble out bike routes, backpacking ideas, rafting trips, more places to explore in Denali, the eastern ranges, the rest of the Kenai Peninsula, it’s just endless. I want more than anything to get back out there again. It brings solitude and adventure like I have yet to find anywhere in the lower 48. Anywhere. There isn’t enough time in a whole summer for me to see everything that Alaska has to offer. But I’ll try. I’ll try to be satisfied. And I’ll be back with a new and better itinerary.

Cycling Denali Under the Midnight Sun

Cycling Denali Under the Midnight Sun

Alaska was a new world for me that summer. I spent months planning a three week trip to Anchorage at the end of June, laying the ground work for what would become three unbelievable bicycle tours across the state, each with its own challenges and rewards. Each tour was unique, and each was like nothing I expected.

I found a hotel near downtown Anchorage with a good weekly rate, booked three weeks from late June to early July 2012, boxed up my bike, and spent a long and shitty flight on a plane that got to the Anchorage Airport at 2 in the morning. It was days away from the summer solstice. A glow of twilight lay over the city, and the air was warm. Clouds hovered above the Chugach Mountains to the east. I went to sleep at the hotel with an odd case of jet lag, thanks to the 22 hours of daylight that Alaska gets in the summer. But I made it. And the next three weeks would entail some of the best tours I have ever done.

Denali was the first place I wanted to go. I have loved mountains ever since I was a kid, and this was my chance to see the tallest one in North America. At 20320 feet, Denali rises three times as high as most of the mountains around it, making it visible for hundreds of miles across the state. I wanted more than anything to see it in the clear. And not just to see it, but to earn the right to see it from a bicycle. I had to get my bike out there, get into the park, and be in good sight of it on a nice day. Everything else about my trip could be a complete failure, and I would still leave Alaska feeling satisfied if Denali decided to appear on my ride.

According to the locals, it shows itself one in every three days. The rest of the time it is covered in clouds. It’s so big that it generates its own weather system, meaning that it can be a great day everywhere else on the range and you’ll still find blizzards high up on its ridges, and shrouds of cloud cover concealing its beauty. My challenge was making sure that I got out to the park when it decided to show itself. For the first few days, this turned out to be a waiting game.

The weather forecast looked pretty hit or miss. So I got comfortable and waited. My whole trip hinged on this, and I could wait as long as I had to.

Later that week I got a message from a local OkCupid girl who I was flirting with, telling me that she was up there, and that the weather was supposed to be good for the weekend. I looked at the forecast again. She was right. Highs in the 70s and clear. I rented an SUV, packed my bike and gear in the back, and got moving around noon.

I got to the park at 4:30, sparing me about an hour to get food and a backcountry permit, and gear up for what I had spent months working up to: An overnight ride on the park road under the midnight sun.

The ranger at the backcountry office gave me a bear canister to bring along. It was huge, heavy, awkward, and almost didn’t fit into my cargo. But durable enough that not even a grizzly bear can bust it open and eat my food. I worked out a schedule with the ranger and was on my way. One day of riding overnight to Wonder Lake, 85 miles to the west, camp for the morning, camp again halfway back the next night, and then finish the day after that at the welcome center. If luck would have it, the mountain would show itself.

I got moving on the paved section of the park road between the headquarters and Savage River, which goes straight along the valley south of Mount Healy, a large 15 mile ridge system of rugged alpine ridges that tower above the taiga forests along the valley. At its summit of 5700 feet, it gives a good view of the Denali massif 60 miles southwest. I pushed onward through the valley under a light shower coming off of the mountains to the south. At this elevation, the forests started to thin out and I could see all of the mountains pretty clearly.

A short descent to the Savage River brought me to where the pavement ends and the fun begins. I stopped at the campground to refill my water and made small talk with a lady staying there with her family. She wanted to know where I was headed. They always do. People see me with the bike and all of my gear, covered in days worth of sweat and dirt, and always want to know where I’m headed. I don’t usually mind. Most of the time I’m ready to see people again after going alone for hours on end.

I crossed the river and started my climb around the side of Primrose Ridge, a small 1500 foot mountain mostly covered in tundra, and a popular spot in the park for day hikes. A short descent down the other side brought me to Sanctuary River and the mountains after it. I made it to the Teklanika River Campground thirty minutes later and took a break. I was making decent time. It was late evening, the elevation was well under the tree line, and the arctic mosquitoes were out in swarms.

From the below the bridge, the Tek River braided its way northward, narrowing through a large canyon and flowing out of the park. The midnight sun lit up the canyon and the mountains around, casting an alpenglow on the landscape. At that latitude it sets for a few hours into the night before coming up again around 3:45 a.m., but never far enough below the horizon that it doesn’t light up the northern sky in orange and gold. People say that the wilderness up there is pristine. When you see the midnight sun casting fire on hundreds of ridgelines, you know they aren’t kidding. I turned south and began my ascent up Igloo Canyon and Sable Pass.

In no time, I left the river, the mosquitoes and the tree line for what turned out to be the hardest uphill climb on the whole road. Ten miles of steep grades and thinning air, along with the fact that it was a dirt road, and that I had heavy cargo, thanks to that fucking bear canister, wiped me out not even halfway up. I was not expecting it to be that rough. But it was outright brutal.

The road went up Igloo Canyon for five miles, the tundra gave way to dirt, and soon I was spitting distance from the tops of ridges on both sides. It turned west for another 5 miles of hard uphill grades along Sable Pass. Ridges passed behind and below, more of them appeared a few miles south, and still, the road turned uphill again and again along the side of Sable Mountain. I stopped to take breaks I don’t know how many times. It made no difference. My training did nothing to prepare me for this. I guess I just had to take my time, something I couldn’t stand to do. I wanted to see the Mount McKinley from a bicycle, and I didn’t care what kind of beating I would end up taking to make it happen.

I pushed on and on between the rocky ridge tops and finally crested the pass just shy of 4000 feet before making an 850 foot descent to the East Toklat River, and then another climb back to the nearly the same elevation along the side of Polychrome Mountain. I was wearing out, standing on my pedals, pushing uphill with a shit load of cargo and thighs burning my legs alive. THIS HAS GOT TO FUCKING STOP. I came around a turn and a big grizzly bear stood right in the middle of the road twenty yards ahead.

SHIT!!!! I slammed on my brakes, sliding on the dirt and gravel. The bear jumped and took off down the hill, disappearing into a thicket of willow bushes. I stood there quietly for a few minutes, listening for it to come back, my heart rate completely off the charts. I was finally sure it was gone, and slowly rode by saying “Hey big guy! I’m not gonna bother ya.. Just passing on by, big fella!” After a hundred feet, I picked up the pace and got the hell out of there.

I reached the top of Polychrome Pass a few miles later. I had been climbing for two hours. Maybe more. I don’t know. But I had to stop and recover my strength. I didn’t have a choice anymore. With no one else out, I had the road to myself, and sat on the edge of a 1000 foot drop off, looking out at the valley ahead. The valley along Polychrome Mountain spans for five miles before sloping upward towards Mount Pendleton and the backbone of the Alaska Range. From there, five glaciers feed its streams, eventually joining the East Toklat further back. It is a diverse and colorful valley, and a popular overlook in the park. I rested for 45 minutes, taking in the solitude and trying to get my head together for the rest of the ride. On the bright side, I was high above the tree line with no worry of the mosquitoes, who I still hate to this day.

I coasted to the rest stop at Toklat River. It was 3 in the morning and I was finished. The rest up on the mountain didn’t do much for me. I undershot the difficulty on this trip, and just wanted to get back to the welcome center. I felt like a failure, but I had had enough. The next mountain pass had a climb of 950 feet, more of the same shit. And from where I was, I was just over half way to my goal. Whatever, I’ll see Denali some other time, maybe come out on a shuttle later the next day after getting some food and sleep. I decided to cut my losses, wait a few hours for a shuttle bus, and go back.

I didn’t even feel like finding a place to set up camp. My morale was altogether gone at this point. So I went into one of the outhouses, locked the door, got my pillow out, and went to sleep.

“Good Morning!” It was 6:00 a.m. A park ranger caught me sleeping in the outhouse. He was laughing.

“Hey uh, sorry, I’ll get out of here in a minute..” I sat up, half awake.

“No, don’t worry about it, get your rest! It’s a good shelter, isn’t it? I’ll go ahead and work on these other ones. Take your time and come out when you’re ready!”

Well that’s cool of him, I thought. I still felt a bit too weird staying there any longer, so I got up and came out.

We made small talk for a bit. He was an older fellow in his sixties, a bit eccentric, and happy to meet visitors. I told him about my trip, how I climbed all of those mountain passes, and was ready to just screw it and go back. He laughed.

“You sure you don’t want to go for it? The mountain is in the clear this morning!”

“No, I think I’ve had as much as I can take of this..”

He laughed again. “Well, you got all the way up Sable Pass, that’s pretty good!” I guess so. But I still felt like I had lost the battle.

I told him about the 500 pound beast that I scared off with my bike last night. “That’s a good bear,” the ranger reflected. “Well, I have to get some work done. The bus is coming in two hours. Just relax and walk around, go up on the ridge over there if you want. The sun should be coming up any minute.”

He went to work on the outhouses and I walked 100 feet up the facing ridge of the river and sat down. The sun had already lit up the Divide Mountain to the south. I relaxed and listened to the Toklat River rushing along, thought about everything I went through to get out there, and then I got my head out of the fog.

What the hell was I doing? I didn’t come all the way out here just to give up and turn around like a pussy. I spent months of planning, buildup, expensive decisions, just to get out to the park with my bike. And then the ride itself was even more trouble. And for what? To turn around and go back, one mountain pass away from my goal. And on a clear day, no less? I would never forgive myself for that. That’s not going to fucking happen. Not now. Not ever.

Fuck it, I’m going.

I came back down the ridge and got my gear together. The ranger saw me and came back over. “Change your mind?”

“Yeah, I’m going for it. I won’t forgive myself if I don’t. How far is it to Eielson?”

“About 13 miles. But you’ll see a better view before that at Stony Hill.”

“That’s doable. I think I can manage it if it’s just one more climb.”

“Yeah, you got a few hours rest, so that should help. Good luck!”

I said thanks, and got started on my climb towards Highway Pass, the highest point on the park road.

The road quickly ascended away from the tree line and into a narrow valley of tundra, and there was nothing easy about it. But I got my morale back, and with some rest, the last bit of strength I needed to climb through the barren, alpine country returned. Trees gave way to grass, grass gave way to dirt, and dirt gave way to rock. I pushed upward for 45 minutes, shedding layers and stopping at different times for water and energy bars. Up ahead, the snow capped ridge of Denali’s north summit appeared slowly at the top of the pass. THERE IT IS!!!! BY THE GODS!!!

More excited and delirious than ever, I crested Highway Pass, crossed a small stream and climbed a few hundred feet to Stony Hill Overlook, the first spot on the road where you can see the whole mountain. There it was, the face of Mount McKinley, the tallest mountain in North America, standing higher than anything I have ever seen. I had no idea that anything could be that huge and that magnificent.

WHAT!!! THE!!! FUCK!!!!!!!! I was out of my mind with exhaustion, hunger, caffeine deprivation, maybe some mild altitude illness. None of that mattered. As soon as I saw it, I knew it was worth every second of pain and suffering I had endured to get out there, at the end of the hardest and most backbreaking bike ride of my life. Whatever. I was there. The rest of the park was still waking up, but I was there, high up on Stony Hill, looking at a vista that would stay with me for the rest of my life, certain that nowhere else in our continent can any range of mountains rival that of Denali and her sisters in sheer size and majesty.

I finally calmed down and kept going. I had four miles left. I descended Stony Hill and went over Thorofare Pass, the last climb of the trip, and easily a short one. Down the gorge to my left, a family of caribou ran along the glacial headwaters of the Thorofare River, a tributary of the larger and more powerful McKinley, which flows westward across the valley ahead for 15 miles before turning northwest into the forested plains and beyond.

At mile 66, the Eielson Visitor Center sits on the side of one of Denali’s facing mountains, offering a great view of the range and a rest stop for tourists, water, restrooms, and a few exhibits. When I got there, arctic squirrels were frolicking around the picnic tables. The first eastbound shuttle wasn’t due for 45 minutes. So I sat down and waited.

Meanwhile, the first westbound bus showed up. Tourists got out and started taking pictures. Then another one stopped with even more people. Before long, the whole place was buzzing with tourists. An older couple saw me with my bike and gear, covered in dirt and a night’s worth of sweat and wanted to know where I was headed. I told them that I spent the night riding out there on the park road, was about to take a shuttle bus back to the park headquarters, get some food, and then drive back to Anchorage. They thought I was crazy, and they were right.

The shuttle bus showed up, I secured my bike in the back, sat down, and fell asleep before my head hit the seat.

The bus reached the welcome center a few hours later, I locked my bike in the rental SUV, got an unbelievably great tasting burger from the park restaurant, got rid of that fucking bear canister, and drove out of the park.

Even when the weather is outright awful, you can still find beauty and magic in Alaska. It’s everywhere. But when the sun comes out and lights up the land, there is really nothing like it. On that day, the mountains glowed an emerald green color in the midday sunlight. White clouds passed above the ranges, casting shadows on the ridges and valleys. I stopped everywhere on my drive back to take pictures.

When I stopped at the South Viewpoint to see Denali, it was already shrouded in clouds again, reminding me that like the rest of Alaska, it’s a beautiful place on its own terms.

I got back to my hotel a few hours later, took a long nap, and walked into downtown Anchorage for some well-earned seafood and craft beer.