In Memory of Iohan

In Memory of Iohan

“I Iohan want to see the world. Follow a map to its edges, and keep going. Forgo the plans, trust my instincts. Let curiosity be my guide. I want to change hemispheres. Sleep with unfamiliar stars. And let the journey unfold before me.”

Iohan Gueorguiev was an adventurer. He captivated the minds of countless people as he traveled by bicycle and packraft across the Americas, documenting his amazing adventures on his YouTube channel in a video series titled See The World. Beginning in the ice roads of northern Canada in 2014, he spent months traversing the Yukon and Alaskan highways before making his way through the American national parks and continuing south through Mexico. After volcano hopping in the Central American jungles and taking a paddling detour around the Darien Gap, he finally reached the shores of Colombia, all while filming and uploading his footage for us to enjoy. Years and countless stories later, he reached the high mountains of Patagonia at Lake O’Higgins before returning to Canada to work and wait through the pandemic.

And that was where his epic Pan-American adventure came to an abrupt and tragic end. The cycling community received a note from one of his touring friends in Argentina that he passed away about a month ago. That he suffered from chronic sleep apnea and insomnia, to the degree that he took his own life to end the pain. So many of us had come to love his videos over the years, and were shocked and saddened that this would happen to such a brilliant soul. I’m still trying to process my own feelings as I write these words.

I followed Iohan for years. He was one of the first people to truly inspire me to go on my own adventures and capture the experiences in video and written word. He had a purity to him that I always admired. His sense of adventure was simple, and genuine. Whether making friends with stray dogs, staying with host families in remote villages, or shooting an epic panorama, he was always able to capture the moment and tell a story that connects and resonates with us.

And so as I go through his old videos, so many things come back to memory. Like the Athabascan woman who sang about Denali in her native tongue. Or when he crossed paths with Sarah Outen on the Alcan Highway. And then camped on a volcano high above Guadalajara. And the time he tried to ride the back roads in Panama, only to see them turn into a mudslide and force him to hitch a ride out in somebody’s truck. And of course there were the incredible panoramas of the remote Bolivian highlands. To the soundtrack of Spanish folk music, Iohan was riding on the bottom of the screen, trying to fit the huge landscapes of the Andes into the picture.

And he was always meeting kind folks and animals along the road. He was a friend among many horses, dogs, cats, alpacas, and townsfolk. And yet, always moving on. Because he wanted to see the world. He wanted to follow the map to its edges and keep going. He wanted to let the journey unfold before him. And then he wanted to share it with us.

It’s impossible to say how many of us have been impacted and inspired by his journey – one so suddenly brought to an end. It never seems fair to see life taken away from someone who lived it to its fullest. But this is a story that will live on. As I speak, a group of his friends are planning a memorial in Ushuaia. I want to see it one day and thank him for sharing his life adventure.

He is Iohan, the Bike Wanderer. And while he may no longer be with us, our hearts are with him in the wilds of Patagonia.

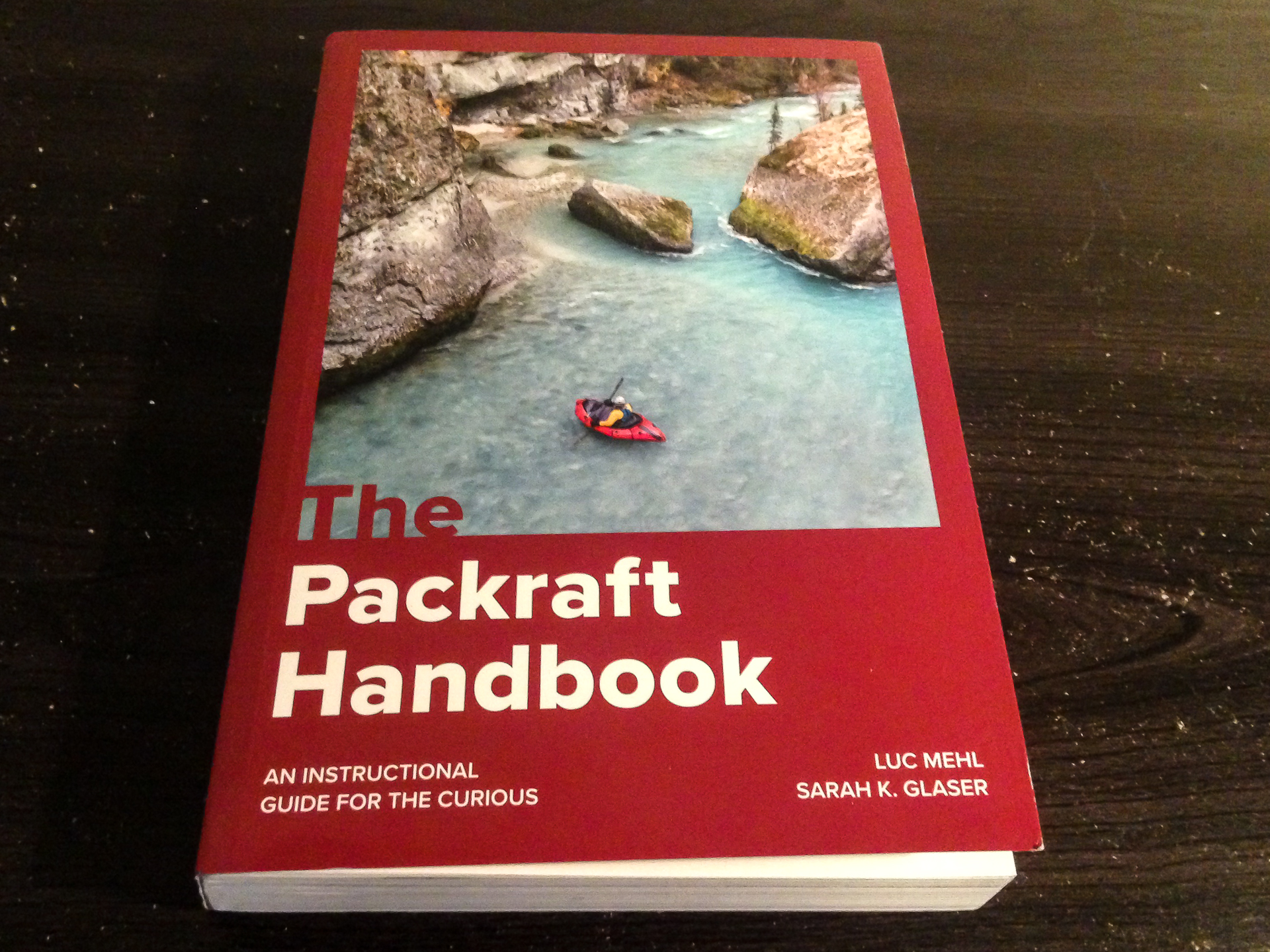

The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl

The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl

Over the last few years, the sport of packrafting has grown from a small community mostly consisting of backpackers in Alaska and Tasmania to people from all over the world – potentially anywhere that you can find runnable rivers that are accessible by foot. In more recent seasons, my feed has exploded with river footage from all across the US, Central America, Russia, Austria, New Zealand, Lapland, Scotland, Japan, and on and on. Which in one sense is great to see so many new people discovering what packrafting has to offer. But as the community continues to grow, so does the likelihood of mistakes, injuries, and fatalities. To date, there are twelve fatal accidents recorded that relate to packrafting.

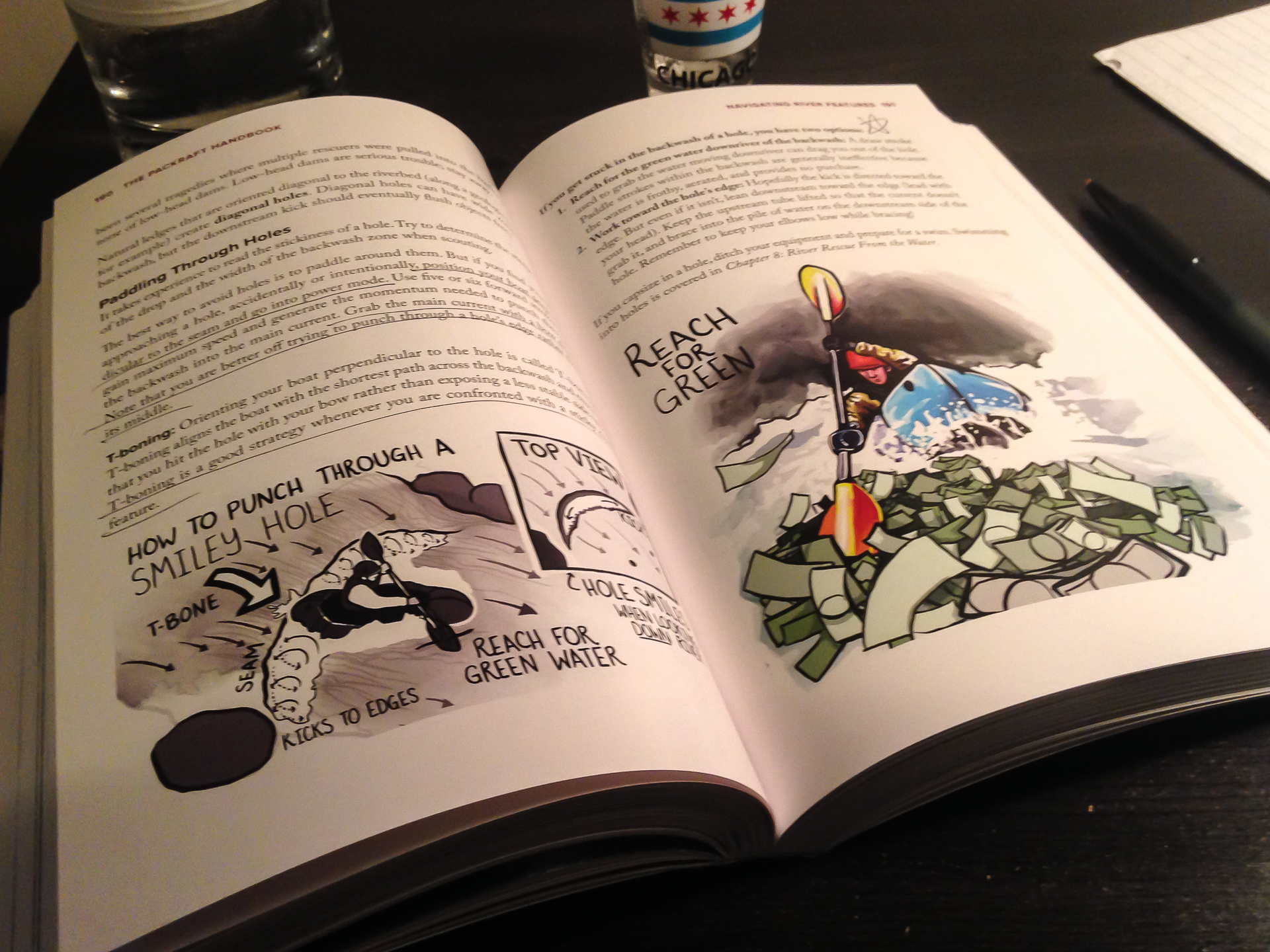

In response to this increasingly important issue, Alaskan boater Luc Mehl published the Packraft Handbook in June of 2021, which is a comprehensive guide to amphibious river running. With the help of illustrator Sarah Glaser, this book provides a very detailed yet simple guide to everything a boater needs to learn – from preparation, to paddling technique, to capsize recovery, and swiftwater rescue. Which I feel is long due in this community. Because while packrafts are generally very stable and forgiving as watercraft, they have given many boaters – myself included – a false sense of security to run bigger rivers where we had no business going without proper training.

It was Luc’s goal to change that trend with this book. By adapting many of the river rescue techniques already developed in the kayaking community to that of packrafts, the book encourages a #cultureofsafety as its core ethos – a community where we can continuously educate ourselves and others on the importance of river safety.

The book is divided into four parts, the first being Foundations. Here, Luc describes the types of packrafts available, equipment, boat control techniques, wet entry, and risk assessment. New packrafters especially will benefit from the knowledge it offers on how to get started.

The second section, Rivers and Open Water, explains the basics of navigating different types of rivers and open water crossings. There are different types of paddling environments with risks inherent to each. Technical swiftwater is different from a windy fjord crossing, but both can be dangerous. It is important to be experienced and prepared.

In the third section, When Things Go Wrong, Luc describes many different types of accidents and the proper rescue response to each, detailing things like self-rescue, throw ropes, entrapment, rolling a packraft, equipment repair, and various examples of First Response emergency treatment that hopefully won’t be needed. I think this section is truly the meat of what we need to understand out there.

And finally, Part 4: Putting the “Pack” in Packrafting has two chapters about planning and logistics. Because it is easy to overpack when you already have to carry ten pounds of river gear. But at the same time, you don’t want to cut too many corners and underpack supplies that you might need, like say, a first aid kit.

It makes me wish I had thought about this four years ago when I made the mistake of running a scary glacial river in Iceland. It was a mile-long river connecting two lakes close to the Jökulsárlón Lagoon in the south coast, and appeared friendly on the satellite. I crossed the first lake and started down the mouth of the river, which was swift but calm. Before I realized it, the current started picking up into a Class II section and I was flying down a center line. Suddenly, I was seconds away from dropping over a river-wide pourover ledge of four feet. And a big hydraulic. With no time to find the line, I charged at it unsuccessfully and got tossed out.

And then I froze. Not literally, but mentally. For about two minutes. Flying down a river.

I thought I could kick my way to an eddy, but the current was too strong. Another rapid was approaching. I snapped out of the fog, threw the paddle across my boat, and lunged forward. I climbed back in and regained control, navigating the breaking waves. Ten seconds after I recovered, I went flying past what might have been a pinning rock.

I had originally planned to run another Class II-III river the next day, but realized as I got to shore that I needed proper rescue training and other partners before attempting something like that again. It could have ended differently. I could have died.

I could have died.

The good news is this this book can give you answers wherever you’re at with your skill level. In my case, I needed more practice at wet exit and recovery. A lot more practice. To the point that it becomes second nature to fall out, flip the boat, and jump back in. I also needed to recognize a wild river when I see one from the satellite. And most importantly, to never go alone on a river like that again. To quote my friend Ben on a similar note, “I lived and I learned.”

Since that trip, I have only done solo trips on easier Class I-II rivers in the Midwest and east coast, usually at the end of the summer when the levels are low. Appalachian rivers like the Shenandoah are nearly all pool-drop flows, allowing for easier recovery between the rapids. And many of them are commercially run, meaning that outfitters are already proactively clearing them of strainers and debris, for pretty obvious reasons. But still, I remind myself that paddling solo will always make me inherently more vulnerable to accidents, and that I need to be extremely cautious. Also, I won’t be running the Gauley in my raft.

But most importantly, I’m due for a swiftwater rescue course – for the benefit of myself and others.

In scuba diving, they teach us that the primary objective of any dive is always to get everybody back safe and unhurt. This is my primary goal of any river trip – for myself and the others to get through it safely. The Packraft Handbook by Luc Mehl explains how. From novice to veteran, boaters of all skill levels can benefit from the knowledge that it offers. So let’s make the #cultureofsafety a worthwhile goal this paddling season.

https://thingstolucat.com/packrafthandbook/

https://swiftwatersafetyinstitute.com/ssi-courses/

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

…continued from Sleeping Bear Dunes

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan is a beautiful area for many reasons, notably for the pristine shoreline of Pictured Rocks, a national lakeshore extending for 42 miles along the coast of Lake Superior. I spent half the day driving up there from Sleeping Bear to spend a couple of days camping and exploring the park. I had enough time that afternoon to hike the Chapel Loop, a 10 mile route outlining the most dramatic section of lakeside cliffs.

I parked at the trailhead and hiked through the forest for an hour, often passing by other hikers before reaching Chapel Beach and the sound of crashing water. Turning west, the trail went along numerous overlooks for five miles. I often stopped to photograph the dramatic cliffsides as tour boats passed below. Eventually I reached Mosquito Beach on the far end of the circuit and turned south on a two mile uphill hike to my car.

It was a great trail, but as I already learned elsewhere, a scenic shoreline can only be fully appreciated from the water. So on the next day I took an all day kayaking trip with Paddling Michigan, starting in Miners Beach just six miles west of the Mosquito trailhead. We paddled east along the steadily rising cliffside, where already the cliffs were layered in different colorful minerals. Sections of them included a layer of gravel left behind by glaciers of another age, grinding and burying moraine into the ancient bedrock.

The water was a translucent jade color illuminated in a bright sun as it slowly shifted about in the calm morning. We passed over a shipwreck, which I couldn’t see very well from the boat. But I did get some video footage of the wooden planks of the ship under the flickering sunbeams. There were other wrecks in the area as well, due to Lake Superior’s potentially treacherous weather patterns. I wasn’t at all surprised to find out that this area has its share of dive sites.

We stopped for lunch on the shore for an hour and then continued on past Mosquito Beach. Here, the cliff points were the most dramatic, rising up to 200 feet above the water. We paddled underneath arches, into cliffside mini-caves, and one small tunnel that waves had carved into the rock wall. I understood why more daring people have taken bigger expeditions into places like Alaska’s Inside Passage, where they can explore its coves, islands, and beaches day in and out. The sport of sea kayaking offers an epic, yet peaceful opportunity to any adventurer looking to find their coastal frontier.

Passing Grand Portal point, we made a straight mile to Chapel Beach, where several people made a 60 foot leap off of a nearby jump rock. The rest of us shored our kayaks as they were already getting loaded onto a shuttle boat. Then we made a three mile hike on the Chapel Trail back to the parking lot.

Great as it was, I barely saw a quarter of the Pictured Rocks shoreline. I have no idea when, but a 42 mile backpacking hike from end to end would be a great way to follow up on this tour.

Sleeping Bear Dunes

Sleeping Bear Dunes

If there was ever a Class 0, it would be the Crystal River in northern Michigan. True to its name, this flatwater river is like a sheet of glass no more than a foot above the sandy riverbed, meandering its way through a dense wood of evergreen to the lakeside vacation town of Glen Arbor. Every summer weekend, an outfitter in the town shuttles people to a boat launch a few miles up the road. I try to avoid spending money just to paddle, and hiked up there on my own.

I set up my raft and got in, and immediately enjoyed the calm and steady current as it made its way through the woods. Many places were a foot deep or less, but usually just deep enough not to scrape my raft on the bottom as I dug my paddle into the sand and grit. I passed several families and on more than one occasion saw kids paddling by themselves out ahead. The truth is that you would have to actually try to screw up on this river.

After about two hours I got to the takeout, packed up, and got a fish and chips dinner at a restaurant close by – the benefits of paddling next to a tourist town.

My plan was to packraft for three days on this vacation – first on the Crystal River, then for two days on the Boardman, a bigger Class II river south of Traverse City. For the past 16 years, the Boardman has undergone a major dam removal project, so far removing three of its four decommissioned dams from the river. I had the idea to spend two days paddling through it with my packraft to see the grassy fields left behind from what were once artificial lakes, and to document the recovering ecosystems. So on the second day, I parked at a river takeout south of the city and hiked the River Road upstream.

Eventually the road crossed over the river and I got a good look at what I was actually dealing with. It rained a lot in the last night, and that river was high. And fast. That along with the fact that camping in the rain already had me in a bad mood, gave me an uneasy feeling about going any further. If I were to go around a bend at that speed and run into a strainer, I don’t know if I would be ready for it. Further on were Class II rapids that I knew nothing about, and also likely higher and faster from the rainstorm. I didn’t want to run it today and end up in the paper tomorrow. So I turned back.

Determined to make something of the day, I got lunch in Glen Arbor and spent the afternoon hiking the trail systems around the Sleeping Bear Dunes. It is a scenic series of sand dunes that span three miles from west to east on the shoreline, with sand bluffs overlooking Lake Michigan and the Manitou Islands across the water. In non-Covid times, you could take a ferry out to them for more secluded camping and backpacking.

I hiked the dune trails as they went along the ridges and scrawling vegetation, occasionally passing dried out husks that were once trees. As the sun fell in the west I parked my car at the main lot and made the Dune Hike straight up and over the ridge system, climbing five or six steep hills before reaching the beach on the far end. I had done this trail before, but it still felt like forever as I cleared each hill only to see another one.

I sat by the water and waited for the late day sun to come out of the clouds that loomed just above the horizon, longing for another sundown of another where and when – one that won’t happen until I’m allowed to return to Europe. It has been a strange and unprecedented year where I had just about everything planned out of where I would go, and what I would do when I got there – only to have life get in the way and change all if it. This week long trip in Michigan might well be the only vacation of note that I take. I, like the rest of America – whether they want to accept it or not – have to wait until we’re not sick anymore. But I’m nothing if not thankful as I allow these times to pass, as surely they shall. There are other worlds than these.

All at once, the sun fell behind the water. I packed up my lensball and camera and made a good pace back in the fading daylight. It was fully dark by the time I reached my car.

This roadtrip continues in the Upper Peninsula.

Rafting the Lower Gauley

Rafting the Lower Gauley

I traveled through West Virginia recently on a train and made the most of the fact that Ace Raft is a three mile hike from the Thurmond Amtrak. Timing had it that I could stop by for the last weekend of Gauley Season and all of the river carnage that it brings. It was October in Appalachia with morning temperatures just low enough to bite. Leaves turn into fire and gold, and the river charges its way down the canyon, thanks to the dam release up in Summersville.

We arrived on a bus at the boat launch just above the Fuzzy Box of Kittens rapid and Woods Ferry, which separate the Upper and Lower sections of the Gauley. It’s a wild Class III-V river throughout, although my paddle down the Lower Gauley today would hopefully be more forgiving. The Upper section is famous for its huge powerhouse rapids that go back to back for 13 miles. And while the Lower Gauley has its share of that too, it is altogether calmer, more scenic, and spaced out. The trip would mostly amount to floating down easy flatwater and enjoying the fall colors and brisk mountain air.

Mostly.

We were just getting started on the second rapid, Woods Ferry, when we ran into a bit of a scuffle. Halfway through, the raft got stuck on a ledge and one guy almost fell out. By a miracle, he landed on a rock and it kept him up just long enough for his buddies to pull him back. The guide, Bobby, yelled at us to paddle, trying to steer clear of the Juicer, a huge slanted boulder at the bottom that nearly always flips a raft. We bumped right into it, and amazingly the boat stayed up and went back into the current.

Our problem was that we weren’t paddling together as a group. You have to go together at full momentum to get the power you need to bust through this kind of water. Bobby had us practice our paddling moves in flat water, but I was still nervous and unsure if we could get through this. It was game time again soon enough. Bobby sent us charging through a huge wave train in Back Ender, then an even bigger series of hits in Koontz Flume, the first Class V of the day. We minded a house sized undercut boulder on the right and slammed through four big wave holes.

My camera died right before Canyon Doors, a calmer, scenic cliffside section of the river. We stopped to eat, I replaced the camera battery, turned the camera on, and we kept going. The river picked up its pace again as we had to navigate the clusterfuck of boulders in Upper Mash. The payoff was that it positioned us to run the main channel on Lower Mash with enough force to slam through the huge wave-hole at the bottom. For what it’s worth, I think we were finally paddling together as a team. As long as we listened to the guide, he could get us through all of it. My confidence in myself and the group was at an all time high.

The only big rapid left was Pure Screaming Hell, a Class V monstrosity known for its disastrously big Hell Hole. Here, you paddle for your life and do everything the guide tells you. Unfortunately, my camera died before we got there, but this video does a good job describing it:

From what I can remember, Bobby steered us on the tongue just left of it for an easier line. I only had a second going by to stare into the face of oblivion. We got through it in good standing, but it did give some boaters after us a thrashing – luckily nowhere near the undercut boulders.

This is a scary river. If you look up documentation about it, pretty much every section with a high rating is loaded with bad rocks. Some areas like Tumblehome are completely sieved out. None of it can be done without a guide or proper whitewater training. But despite the threats, I just can’t pass up the chance to see the beautiful bigwater Beast of the East, the Gauley on dam season. Even if it means I have to spend one boring final hour floating down flatwater to the takeout. It was late afternoon by then, and all I could think about was beer and pizza.

I went back to the lodge restaurant for both, slept in a cabin tent, and hiked back to the Thurmond station the next day.

Green River Revival at USNWC Charlotte

Green River Revival at USNWC Charlotte

Every year on St. Patrick’s Day, the US National Whitewater Center hosts the Green River Revival, an outdoor festival centered around a huge artificial whitewater course in Charlotte. It draws thousands of people in green apparel, blankets, dogs, kids, and beer. Runners warm up for the Color Me Green 5K, kids ride across the park on the ziplines, people climb rock walls, and boaters of all skill levels paddle the green river.

I’ve only seen these rapids on Youtube, which isn’t saying much, but today I’m going to run them in full color. But first I want to get aerial footage of the river. I find the zipline tower, mount my camera on a helmet, and spend 90 minutes going back and forth on the ziplines over the park. At 1:00, they release the green powder, which bleeds its way down the channels. Crowds of people cheer, and boaters in all kinds of watercraft follow the green streaks of river dye down to the lower pond.

I walk around and scout the greenwater channels. In this park there are two: A fast Class III-IV channel to the right and a longer, slower II-III to the left. Beginners go left. Nonetheless I want to at least see what the harder one entails. It is an almost continuous rapid of big Class III waves for the first half before it passes in front of the welcome center and the restaurant. Near the end it drops into a huge, thrashing hydraulic with turbulent eddies along both sides. I see kayakers run it by skirting the eddy line on the left, hopefully missing the meat of it. In a big raft you would just punch through the apples. My little boat would surely get tossed around like a new fish.

I feel better scouting the left channel. It starts with manageable Class II waves for the first half, eventually speeding into a nearly continuous series of Class III wave-holes – and one notoriously big M-Wave in the middle. More on that in a second.

I suit up and paddle to the top, dropping over a small river-wide ledge and going straight for the first of several well-spaced play waves. I pass groups of kayakers along the eddies, who typically wait their turn to flip around in the current. The channel splits around an island, rejoins and starts picking up speed. Out ahead it constricts under a bridge, creating a fast pourover that rushes straight into a snake tongue and the big ass hydraulic that they call the M-Wave. A guide told me to run it on the left so I wouldn’t get smacked in the middle. I take his advice, clearing a small wave under the bridge and charging as hard as I can along the left side. I need the right amount of inertia and balance or I’m joining the swim team for the rest of this. I slam into the wall of foam, pulling a hard stroke right through the pile.

Holy shit, I cleared it! I’m flying down the channel, fighting to keep my boat straight. I barely have time to celebrate before I’m closing on another big swell. I clear that one with a clean lateral stroke. A hundred feet ahead is another hole that could toss me out, so I eddy out to the right, pass it, and continue down the middle. More laterals try to surprise me, but it feels like a straightforward path to the bottom. A big lateral wave at the very end sends me headfirst into the glassy, Jolly Rancher colored greenwater. I wash out and recover in the bottom pond.

I swear I have a love-hate relationship with this sport. These kinds of swiftwater rivers have created some of the most amazing, memorable trips I’ve ever had – yet I’m often equally as frustrated after capsizing and washing out. My excitement is just as real as my uncertainty, and I can never seem to get my head around it. How the power of water can create this dangerously amazing way of life. But this is what I do. #thisispackrafting

I sit at the restaurant as the day is starting to wind down. Boaters are still hitting that mean looking Class IV that I’m definitely not running today. I drink an IPA because the menu says it’s from a brewery in Charlottesville. I’m heading that way on a train later because I’ve never hiked Old Rag before and now is as good of a time as any. My life has had a lot of firsts as of late.

So yeah, greenwater rafting. Come out to USNWC Charlotte next St. Patrick’s Day to see it for yourself. I enjoyed it, though my only real serious complaint was that I didn’t see any green beer. Nonetheless it’s a fun river trip, and you can even bring leprechaun sunglasses if you’re feeling festive.

Appalachia By Train And Raft

Appalachia By Train And Raft

The Amtrak Cardinal and Capitol Limited lines travel from Chicago to the east coast nearly every day, allowing access to a number of popular, runnable rivers. With a packraft, reaching them is an easy matter of packing up my river gear, riding on a train, and hiking out to a boat launch. On this tour, I combined three different Appalachian river trips into a week-long itinerary of train rides, paddling, and hiking.

Day 1: Packrafting the Potomac

I leave the train at midday and find the riverside trail going west. The river rapids of the Potomac echo through the trees. The afternoon sun is hot and my pack is heavy. I walk for two miles and reach a boat ramp owned by a local tubing outfitter. The guy tells me to stay away from river right. It has collected a lot of debris from flooding and one section of it is sieved out. The reality of this advice, and the collective roar of swiftwater a thousand feet downriver is making me nervous. I’m scared of it. But I can’t look away.

I’m back in Harpers Ferry for the fifth time, setting up to run my packraft on the Potomac River past the town to the 340 takeout downstream. It is a popular Class I-II section of intermittent ledge rapids, drawing a lot of open top kayaks, canoes, duckie boats, innertubes, and every so often some dude with his own green inflatable boat and GoPro that he rigged off of the stern.

I launch out and paddle to the left side, looking for a runnable line through the rocks. Little channels pour every different way and I’m forced to navigate on the spot. I recall seeing a straight current to the right in the satellite view. But since that section isn’t safe, I have to paddle through a boulder garden, often ferrying along ledges to find a way through. My camera keeps going out of position when I go over a wave, because there’s no way to fully tighten the ball joint on my tripod. So I keep having to fix the camera position, which is the most important thing about this trip, because I’m all in it for the Likes.

I paddle fun, bumpy rapids for a quarter mile, then pass the town and the confluence with the Shenandoah. The river widens. I hear another rapid ahead. Again, left is the way through. As I go east, the clouds behind block out the sun and the valley darkens. I need to hurry.

The river channels into Whitehorse Rapid, the only wave train of any notable size. Even so, you could run it in an innertube, fall out, and float harmlessly to the end. I skirt the right edge, ferry to the boat ramp, pack up, and scramble up to the 340 bridge. The hostel sits on a bluff on the other side. It’s my fifth time staying there.

I usually travel alone because I like to do everything on my own terms, but the more extroverted part of me likes to meet people when I do. Which is why I like hostels. They bring adventurous people together in an environment that allows travelers to connect with each other, while at the same time continue on with whatever their thing is. The one in Harpers Ferry is particularly interesting because it hosts a lot AT thru-hikers, cyclists on the C&O, people on roadtrips, and guys like me coming out and doing random shit.

This time I meet a group of 25 people from DC on a cycling meetup. They rode out here on the trails, plan to hike Maryland Heights and go tubing tomorrow, then ride back the day after. When I meet them, I realize this is a demographic of people here that I had never considered: weekend warriors from DC.

I have beers and shots with them as we trade travel stories and river trips. One girl is bringing her kayak to Gauley Fest in two weeks. Another one has questions about Iceland. And another one is a government security employee who wants to get out of it and travel more. So do I. If it were up to me, I would be nomadic and stateless – traveling, taking pictures, making videos, writing stories. But vacations will have to do for now. I finish one more beer with them at a bonfire and go inside to my dorm.

Day 2: Capitol City Layover

I hike back to the town and board the eastbound train in the late morning. Even with my ultralight gear – packraft included – I feel like my pack is weighing me down. I have to get rid of this thing if I’m going to find a brewery. When I get to DC, I check it in with the agent and go outside. Without it, I can walk around instead of hike, if that makes sense.

I load up Google Maps and put in “Brewery”. Twenty minutes later, I’m at Capitol Ale House sitting in front of a colorful flight. Vanessa is texting me something funny. We talk a lot, even though she is in Sweden and I’m in the states. I met her on a trip last year and we have been talking about Sigur Ros over WhatsApp ever since. I send her a link to a B-side from Julianna Barwick, whose angelic voice can melt a heart of stone.

I leave Union Station on the Crescent train for my hometown.

Day 3: The Shenandoah by Packraft

I drive north and park my parents’ van at the Inskeep launch three hours later than I meant to. It takes me 45 minutes to set up the raft and sort my gear. I get moving on the river at 10, losing most of the good hours of the morning. The Shenandoah is mostly calm, opaque and brown from rainstorms washing dirt from the mountain streams. It’s low but has one or two good feet above most of the ledges, often enough for me to get through without looking for a line.

Halfway through the day, I start passing large groups of tubers and kayakers. Why didn’t I think of this in college? I lived in Harrisonburg for years and it never occurred to me that a crew of us could float this river. Complete with outfitters and coolers of beer, we could have been 20 strong. But the truth is, there is a lot of natural beauty in the Blue Ridge Mountains and West Virginia that I took for granted back then. Hell, the AT is 12 miles away from the farm. But that’s why I keep coming back now. I’m making up for lost time.

The day gets hot and I’m running out of energy. It’s my own fault I didn’t start earlier. I have to get focused, because I need to scout the Compton Rapid, considered locally as the boogie rapid of the river. I climb through bramble to get to the riverside and take a look. I can see the line clear as day. You start it on center right to miss a ledge hole on the left, and then work your way left to avoid another one on the bottom right. I easily run it to the bottom.

I take out at Mile 19 and dry my gear in the sun. It’s late in the day and I’m exhausted. I hike the Indian Grave Trail a few miles up the ridgeside and find a flat area to set up camp.

Day 4: The Most Convenient Shuttle Ever

I pack up and keep going up the ridge. To my right I discover a spring and refill my bottles. The trail steepens as the 9am sun shines between the trees, already hot in the morning haze. In its steepest part, this trail is like a staircase of rocks cutting into the mountainside. The sun beats on my face and arms. I see the Shenandoah meandering below the humid backdrop of the Blue Ridge.

I reach the ridgeline of Massanutten Mountain and turn south. On a map you can see it circle around Fort Valley to the west, a small, solitary valley a few miles wide. One road goes through it from 675 to the valley’s end, 20 miles north. Even after all these years it’s the first time I’ve actually seen it.

I go south as the sun rises to an unforgiving angle. There are a lot of exposed rocky areas on the trail that offer little shade. When I do find it, I often stop to catch my breath and bring down my core temperature. I’m supposed to hike 11 miles to the trailhead, but with three full bottles and nowhere to refill on the ridge, I’m starting to have serious doubts if I can ration enough water for this.

What I do know is that Habron Gap is 4 miles from Indian Grave where I started. If it gets too hot, I’ll hike back to the road from there. I spend two hours fighting my way over ridgetops, and eventually get on a steady decline to the gap.

When I reach it, I have to decide. I can ration what I have left for seven more miles to 675, or I can hike down the ridge from here. I realize that even if I do have enough water, I would still be miserable in this heat. I take out my phone and look at the terrain map. Shenandoah River Outfitters is three miles down the mountain. I have to get from the blue dot to the red pin.

I finish my second bottle and start down the Habron Gap Trail. It’s smoother than Indian Grave, with less bramble growing along the sides. It goes steeply down the high ridge for a mile before leveling out in the trees. There, it flattens and I pick up my speed. It’s good to be in woods again.

Fifty yards to my right I hear the rush of a mountain creek. I go over, drink my last bottle, fill up all three, drop tablets into each, and keep going.

Finally, I make it to the road. I hike one last shitty mile to the outfitter and ask the lady where I can refill my water. She says there is a hose around the side of the building.

“Okay. What would you charge to shuttle me back to the Inskeep launch?”

“$30.” DONE. Twenty minutes and two Powerade bottles later, I’m loading up the van and driving out.

Several years ago, I stopped at the Thunderbird Café after another river trip, solely because of the name. I go there again, feeling like this might become a tradition. When I sit at the counter, I drink an extra glass of water. Just because I can.

Day 5: Hometown

The Shenandoah Valley is home. And it doesn’t matter how much time I spend away from it or how much I change, it will always be home. Though I’m too restless to ever move back here, I generally feel like I need to come back about once or twice a year to the quiet town – for the familiar hills, the fireflies, the sunrise on the Blue Ridge, and the sunset over Betsy Bell. Even the Walmart is part of my old life.

I borrow the van and visit my college friend Pete for coffee. We meet up nearly every time I come back. He and Jill had just recently lost their dog of many years and adopted a new puppy in her stead. As somebody who grew up around dogs for half of my life, I get all too well the grief of their loss, and how the joy of a new puppy can heal a family of that sadness.

Pete leaves for work I drive to Gloria’s Pupusaria, because there is no such thing as too much corn masa. Later, my dad drops me off at the Staunton depot, where I once again leave my childhood home for a westbound adventure.

Day 6: Packrafting the Greenbrier

The river is six miles away. I plan to head out of White Sulphur Springs at 4am, determined not to make the same mistakes as before. But first, I eat a fruit breakfast my AirBnB host had prepared for me, and cut slices of the best artisanal cheese bread in the universe.

I hike out on the street in the dark, passing by the entrance to the Greenbrier, a huge world-class resort on the western edge of town, complete with a golf course, casino, spa, lavish weddings, expensive rooms, obscenely rich people, and the one thing I actually am interested in seeing: A decommissioned fallout bunker. The Greenbrier offers tours to their guests and the public to view the resort’s Cold War era fallout shelter, built to protect over 1,100 government officials from a nuclear disaster.

Maybe next time. I would need an extra day and I’m on a schedule. I walk by a parking lot and sit on a rock wall to rest. A security guard is just finishing his graveyard shift and offers me a ride. I load my backpack in his truck and get in the cab. He drops me off close to the interstate exit, a mile from the Caldwell boat ramp. I’ll take it. I get there and start setting up my raft at daybreak, which is the point. But first, I eat the artisanal cheese bread for breakfast. It is everything you ever want bread to be and more.

A canopy of fog hangs over the Greenbrier River and small patches of mist linger above the glassy flatwater. I push out and float into a smooth current. For six miles, I paddle through easy, bumpy Class I sections and the morning brightens. This is a scenic “family float” section of the river from what I can tell. I, however, do not waste my time floating anything, but make a hard pace in the cool morning.

The mid-morning sun breaks through fog and I pass the bridge at Ronconverte. A young fawn stares at me curiously from the river’s edge, perhaps the only eventful thing that happens before the valley narrows into a canyon. We stare at each other as I float by, careful not to spook it off.

The river bends sharply several times below the canyon’s cliffsides, passing from rapids to deep, clear flatwater pools. I think about why I do these kinds of trips. How the energy of a river really does accentuate the beauty of a landscape. When it’s calm, it brings out the peacefulness of the countryside in a way that never quite happens on foot. And when it’s fast and wild, its beauty is amplified through its crashing water and echoing roar across the valley. I never feel truly alive like I do when I’m fighting my way through a wild river rapid to its peaceful end. Because ultimately, the river does what it wants. And I have to enjoy the river on its own terms.

I get out at Fort Spring to eat. I’m two miles from the campground, and two rocky rapids as it turns out. I go around two bends and hear a loud roar ahead. Most of these rapids are small enough for me to eyeball a line, but this one doesn’t have a clear channel from the top. The main channel in the middle goes right into a rock at the bottom. Dammit, I have to get out.

I scout from the left. Sure enough, the center line would be fine if that rock wasn’t waiting to smack into my boat. The far left line right in front of me looks more promising. It’s tight, but I can get it with a quick right turn. I get back in and run through it as planned, but not without scraping the bottom. Good thing my packraft is made for that kind of abuse. I’ve hit rocks with it so many times and have yet to rip a single hole anywhere.

I get to another rapid and try to scout from the top. The current is too fast and I have to improvise. I go for the biggest channel I can find and get stuck on top of a rock just under the current.

Shit! Water is rushing around me on both sides. I lean out and put my paddle in the current, well aware that I don’t want to fall out and chase my raft down this bony ass rapid. Soon I’m freed and go out on the current backwards. I spin around and charge out on the tailwaves, staying clear of more rocks on the right.

This had better be it. Without a doubt, rapids like those are easier at high volume, even if it means bigger waves and higher whitewater grade. But today the river level is rated “Lower Runnable”, requiring more technical lines around the rocks.

I shore in at the campground and set up close to the river. When I go to the office to check in my site, I hear the meow of a kitten from behind the front desk. The lady tells me that it hitched a ride with her to work today. Apparently, the cat climbed through the engine of her car and sat just under the hood that morning. She got in the car and drove to the campground, and when she got out, she heard it meowing from under the hood. When she opened the hood to look, there it was. Not a scratch. Somebody has a guardian angel.

That night, a thunderstorm passes over the valley. I barely notice as the downpour bombards the rainfly on my tent.

Day 7: Take Me Home

The depot in Alderson is five miles away. The river, according to the campground website, has more rapids like the ones from yesterday. I’m reluctant to paddle any further. The last thing I want is to fall out in some bony rapid and hit my leg on a rock. Instead, I pack up and hike on the road.

Stuarts Smokehouse is well known on the river, very largely because they have signs that say things like “Pulled Pork & Brisket at Stuarts, 5 Miles!” I make a strategic three mile hike to get there at 11 when they open for beers and a brisket dinner. Outside, the sign reads “Cold food, warm beer, ugly women.” Sold!

I reach Alderson and wait out the afternoon at the train depot. Several boring hours later, I board the train one last time with my river gear in my backpack.

Later, the golden sun lights the fog gathering at the top of the New River Gorge as #51 passes under the high bridge and out of the canyon. It has a trail system and river of its own – also accessible by the Amtrak Cardinal.

Part 3: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

Part 3: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

…continued from Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

Day 5: The East Fjords

The northeast country was the most diverse terrain I had ever seen. I cleared a ridge in the morning, revealing the vast, open lava fields of the Skútustaðahreppur region. A huge plain of lava rocks and ash spread out across the land. It was everything Iceland is – picturesque, dark, otherworldly, like nothing like I had known. I grew up in a country with millions of acres of deciduous forests, foliage, deer, black bears, and catfish. But here, the calderas, hot springs, snowfields, and glaciers continuously shape the face of the land. It had the openness of Alaska and the emptiness of a lunar landscape. This country was a geologist’s paradise.

There was one particularly rough mountain pass that I cleared at midday to reach the coast. It was graded at 12% downhill on gravel, with switchbacks. The fact that I was still new to driving a manual transmission didn’t exactly help. I swore a lot as I turned at each switchback in a low gear, worried that the van would tumble off the road and roll down the mountainside. But I made it and the road leveled off as I approached the East Fjords, easily one of the most beautiful regions in the entire country.

I drove until mid-afternoon and stopped at the coastal town of Hofn. Natalie reported her status on Facebook. She saw the auroras a few nights ago. I was jealous, even though I had no reason to be.

I left the campground to get a drink at a nearby restaurant. When I looked at their expensive menu, I almost walked out. This restaurant had burgers for $40, a BLT for $40, and entrees going at $60 – prices which unfortunately aren’t that uncommon in Iceland, thanks to their huge tourism industry. But then I saw something better for less: Icelandic pancakes for $12. Now we’re talking.

They brought me a hot pancake with whipped cream, blueberries, syrup, and lots of decadence. I would do it again in a second.

Day 6: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

I figured out that I could stream music from my camper van’s wifi. When I plugged my phone into the dashboard USB, it played the audio through the van’s speaker system. Hell yeah? I wish I figured this out earlier. I loaded up an ambient Spotify playlist and drove the southeast coast to the likes of Hammock, Brian Eno, Caspian, Julianna Barwick, and others who would complement the open road. To me, epic landscapes like these always seems to bring out more depth and nuance in my music. And perhaps the music itself amplifies my sense of adventure as I wander into new lands. I didn’t know it at the time, but as the soundscapes were building and I approached the lagoon, this would be the most exhausting day yet.

I parked at the main lot of the Jökulsárlón Lagoon, a huge glacial lake on the southeast coast. It was one of three lakes that I planned to traverse that day in my packraft. But first, I wanted to see Diamond Beach. The glacier above the lagoon frequently calves, sending huge icebergs across the lake that eventually reach the mouth of a small river close to the road. They break up and wash downstream and into the ocean. The tide then washes them back onto the black sand beach, creating ice diamonds.

I went back to the van, got my gear, and hiked along the east side of the lagoon to find a good launch point relatively clear of the bigger icebergs. The rangers warned me that they could flip anytime, causing a bad accident. I paddled into the lake, far enough from what could have been a dangerous calving.

The Breiðamerkurjökull Glacier to the north was massive. On a map it is about 8 miles wide. There was no way I could fit it into a camera. I paddled across the lake for an hour with that huge glacier to my right and countless icebergs to my left. I got to the other side of the lake, packed up my raft, and started walking the marked trail between there and the lakes to the west.

The trail went over five miles of moraine, but felt like longer. Soon, I was on the higher hills, looking down at the braided streams of glacial meltwater that fed the lake below. The path was defined by trail markers that went on for two good hours before reaching the west end of Breiðárlón Lagoon. I planned to paddle it for a mile to the mouth of a small mile long river on the south end, float the river to Fjallsárlón, and hike back to the road from there. I easily paddled across the lake, luckily without any wind to complicate my route. In a packraft, the wind can take you in any direction it wants, and probably not where you want to go.

I reached the mouth of the river and scouted the rapids at the top. It didn’t look like this on the satellite. I expected to see an easy, floatable river between here and the lake downstream. But this river was fast with a lot of Class II. Well, I’m nothing if not adaptable.

I navigated mostly on center lines through the top rapids. I approached the third rapid about a half mile downstream and positioned for the middle to avoid some holes on the right. I thought I was cruising. Then out of nowhere, I approached a river-wide pourover ledge of four feet. Fuck, I should have scouted it. The swell went over and piled into a big hydraulic. I charged at it, hoping to bust through. No luck! It pulled me back in the hole and I flipped.

Luckily, there was no retention. I washed out of the rapid and went straight into another Class II. Shit, where’s my paddle?!! I spotted it 10 feet away to the left. It was partially submerged with one oar bobbing out of the water. That’s a first. I kicked for it and got it easily. Still pretty unnerving. I waited out another rapid, hoping for an easier break to self-rescue, and got back in just before another rapid was on. As it mellowed out, I scrambled into position and eddied out to the left to get my bearings. I got to the shore and stepped onto firm gravel. That could have gone better.

I love to run big rivers, but wipeouts like that one always freak me out. I wasn’t planning on running swiftwater at all that day. In this case, what looked like an easy float from the satellite was far from it. That said, it can be done if you mind the ledge in the middle to scout and/or portage. I didn’t do either, but I’m sure it has a runnable line.

The satellite said that there were two more rapids before it turned to the right and opened into the lake. I scouted them both and planned on a center line. Pretty much everything on that river was a center line except for that fucking ledge.

I was discouraged, but I kept going. I easily cleared the last few rapids on the river, and went around one last bend. The calming water carried me into the lake in full view of the Vatnajökull Glacier. She smiled back at me as I floated peacefully into quiet water.

I shored in, packed up, hiked back to the road, and eventually got picked up by a traveling German tourist.

This story continues in The Golden Circle.

Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

…continued from Part 1: Jetlag in Reykjavik, Diving the Silfra Fissure

“For all its material advantages, the sedentary life has left us edgy, unfulfilled. Even after 400 generations in villages and cities, we haven’t forgotten. The open road still softly calls, like a nearly forgotten song of childhood.” -Carl Sagan

Day 3: The Ring Road

I think every traveler should drive the Ring Road at least once in their lifetime. As the main highway in Iceland, it circles around almost the entire country, offering some of the most diverse and interesting landscapes you will find anywhere. I had considered the idea of a cycling tour around it, which lots of people were doing, but decided instead to drive its 828 miles in a vehicle.

Lots of people travel to Iceland, rent cars, and go on roadtrips around the country each summer. I didn’t want to stay at expensive hotels and didn’t feel like bringing my camping gear. Instead, I rented a camper van and spent six days driving, exploring, and sleeping. Equipped with a pullout bed, kitchen, stove, table, chair, wifi, and pretty cartoon decals, it had everything I needed to live for the next week.

I loaded my backpacks and suitcase into the van and drove out of the rental agency in the late morning on the beginning of a weeklong roadtrip around the island. But first, I made a stop down the road at the Blue Lagoon, a popular geothermal spa close to the airport.

I’m not much of a spa person, in case you haven’t guessed. But even I could appreciate that lagoon for its natural beauty and decadence. It felt surreal to float in the hot blue water, surrounded by piles of lava rocks. I almost wanted to put some of that exfoliating shit on my face. I didn’t do it, but it also has a fine dining restaurant, island bar, saunas, and massages, if you’re into that sort of thing. Thanks to the island’s geology, there are lots of hot pools like this one in Iceland, though this one definitely gets the most attention.

I got out, dried off in the sun, and drove northward through the city, planning to get to the north country by sundown. The highway in Reykjavik had a lot of roundabouts which were tricky at first to manage on a stickshift. I had just recently learned to drive in manual specifically for this trip. The rental company didn’t have any automatic cars, which I didn’t notice when I made the reservation earlier that summer. So it was either learn on my dad’s farm truck or I don’t get to drive in Iceland. A stressful, yet productive goal.

The road narrowed into two lanes and I left the city behind, going north along the coast on an uncharacteristically sunny late afternoon. I mounted my camera to the windshield to film a timelapse video of the drive. The shutter went back and forth hypnotically for hours as I captured many mountains and towns in the late day.

I turned east, ascending into the hill country, a region quilted in farmlands. I passed countless horse ranches and sheep farms that were almost never fenced in. Sheep wandered freely, sometimes onto the road.

As the evening darkened I drove up another big hill when my camera suddenly stopped. At a glance, the screen revealed “Error 20: A malfunction with the mechanical mechanism has been detected.” What the hell is this? I restarted the camera and turned the shutter interval back on. After a few minutes, it stopped again. I concluded later that night after Googling quite a few message boards that the shutter hardware was starting to wear out and it needed to be serviced. Well, shit. This wasn’t an option on this trip, nor was replacing it in Akureyri for $800. So it meant that I could only get drivelapse shots of the first day. Which was a shame, because this wasn’t even the best part of the road. But luckily, I could still point and shoot, so it was functional enough to be useful.

I arrived at the town of Varmahlíð and turned south on 752. I pulled into the gravel parking lot at Viking Rafting and parked behind the main building, and went inside to ask if I could camp in my van. Eight river guides and support kayakers were sitting on couches and watching an extreme kayaking documentary. I liked them already. After watching a video of two guys dropping treacherously through a slot canyon in California I went back to the van, cooked dinner, and slept. The light faded and the temperature dropped.

Day 4: The East Glacier River

Iceland would have lots of perfectly great, runnable rivers if so many of them weren’t punctuated by dangerous waterfalls. Although they’re great to look at, they’re not so great to attempt in a raft. An exception is the East Glacier River, an awesome Class IV canyon in the north country, where the waterfalls that once existed have been washed out by the continuous pounding of water. It was a river trip full of big hits, fast gradients, sheer lava rock walls, crashing hydraulics, and lots of noise and swearing – exactly the kind of river trip I was looking for.

I was one of three people who signed up to raft on the East Glacier that day, the other two being a newlywed couple from Canada. They had the right idea. If you’re going to honeymoon, you do it right. Do what I do. Go to Iceland, rent a car, bomb a river. We geared up in the main building and left in the shuttle bus for the river launch, 45 minutes on a dirt road from the headquarters. We arrived and sat next to the river while the guide gave us a 30 minute orientation on river safety. He emphasized that we needed to smile and have fun if we fall out to avoid panic – something I in my shortsightedness could have done better. More on that in a minute.

We put on our drysuits, walked the raft to the river, and eddied out into the current. The trip was supported by a kayaking photographer and two rescue kayakers who went out ahead of us in the bigger areas with throw bags and lots of river rescue training. I met support staff from Nepal, Uganda, New Zealand and Alaska – all living and working at the river outfitter for the summer season. Though we were all from different walks of life, there is one thing that always brings we river rats together: We love to run wild rivers.

The entrance rapids were fast and easy as the current rushed through the canyon on a high gradient. We floated past numerous sheer walls in a river 20 feet wide, sometimes less. The first big rapid of the day, Alarm Clock, threw a huge splash my face like a bucket of cold glacier water. We went around sheer bends of rock as the current tumbled its way through numerous Class III wave trains.

Commitment Rapid was next, and was a huge Class IV pourover that flipped the raft and threw all of us out. I felt the current pull my paddle out of my hand, and another rafter caught it as it washed out into the left eddy. Soon we were back in the boat for more. Game on.

After 20 minutes, we eddied out and the guide explained the strategy for Green Room, a technical Class IV triple drop. It turned out to be a monster. We didn’t even get the first drop correctly. The boat flipped again and I was back in the water, flying down the rapid. The current sent me over the second drop. One of the kayakers in the right eddy yelled something at me. I couldn’t hear him. The swell took me over the third drop and into a huge wall of foam.

I expected to wash out of the hole after a few seconds. That didn’t happen. SHIT! IT’S RECIRCULATING!!! I continued to tumble underwater in what felt like an office sized washing machine. Was I stuck in a recirculating hole? What the hell was going on? It felt like an eternity. FUCK!!! I’M NOT COMING UP!!! I need to get out of this now! On other whitewater trips they told me that if I ball up then maybe it will send me back out of the–

I’m out! I can breathe!!! The rescue kayakers were right there, almost like they expected to see me. “Swim to the eddy! Swim to the eddy!” I went for it, but was too tired. They had me grab on the handle on the back of a kayak and ferried me out of the current. The guy snatched something orange out of the water. It was my camera. It fell off somewhere in the middle of all of that shit. He let me go at the eddy and I swam for a rock on the edge. I clung to it as the water pulled at my feet and scrambled ashore – too out of breath to stand, but more alive than I’ve felt in years. Fucking shit, that was crazy.

Turns out I was perfectly fine. That rapid is called the Green Room because if you go far enough into the undertow like I did, you will find yourself surrounded in ambient green light. But without fail, it will eventually spit you out at the surface. I didn’t try it, but the Lower New River has the same feature called the Elevator Shaft. Boaters jump in, get pulled down, and come back up twenty feet away. The casual way the guides joked with me and the other girl who it happened to later was reassuring. I wasn’t really in any danger.

We eddied out to the left to take a break. I heated up my core temperature with hot chocolate and waffles with whipped cream, berry preserves, chocolate syrup, courtesy of a local farmer at the top of the canyon. For years, he has been feeding rafters at this spot. He used to climb down by foot, but at some point rigged a pulley system to lower the food to hungry, cold boaters. Every day. For years. That’s what he has been doing. I can’t even begin to describe how good of karma that is.

Later, we approached a big wave hole and our guide asked us if we wanted to surf it. Usually this causes boaters to fall out, which is often what the outfitters are going after. Because let’s face it, as scary as they get, the river wipeouts do make for the best pictures. I looked at the calm water right after it and thought why not. I already got pummeled upstream anyway, what difference does it make? Sure enough, we got tossed out and easily made for the right eddy.

Jump rock was next, a big 30ft cliff jump near the end of the canyon. I wasn’t intimidated by anything at this point.

The river slowed down and the walls widened, eventually sloping into hills and farmlands with higher mountains far off into the distance. It was calm, easy, scenic, and a great way to end a wild river trip. We packed up and went back to the headquarters where I got a CD burn of the camera boater’s pictures. The Floatie Back Door on my GoPro is the only reason why it wasn’t lost on the riverbed.

I had a few hours of good daylight left. I drove east. I went over a mountain pass, drove past the town of Akureyri, and camped next to Mývatn Lake, one ridge away from the vast lava plains of the northeast. The red sunset brought peace to an otherwise wild second day on the road. So much has happened. But I was just getting started.

This story continues in the fjord country.

Cave Kayaking in Belize

Cave Kayaking in Belize

I was originally supposed to cycle through the Rockies this summer. I planned an awesome route from Denver that went west over a huge mountain pass of 12,000 feet, and then looped back to Denver over a three day trip. But when I realized that I wouldn’t have much time to acclimate to the elevation change, including one morning of riding from 9,000 to 12,000, I would be putting myself at risk of an altitude injury. It would be one thing if I lived out there, but I’m in Chicago at 600ft. It was a terrible idea, so I scrapped it and went to Belize instead.

Direct flights from Chicago to Belize City can easily go for $600, which is bullshit. Instead, I flew to Cancun for half that much and took an overnight bus across the border, getting into Belize City at 7:30am. The pickup location for the kayaking trip was a mile from the bus station. It was already a hot morning with the sun beating on the side of my face. I had gotten six hours of sleep in the last two days and felt like shit. I didn’t care. I was about to paddle through a river cave, and that’s way important than sleep.

I met the guide at the terminal and we waited for a few other people. Soon, I left on the westbound highway in a shuttle with other Americans on a 60 minute drive into the country. Belize gets a huge number of American tourists – perhaps because it is the only English speaking country in Latin America – and perhaps because its beaches and jungles are amazing places to visit.

We got to the park and geared up for the trip. We hiked on a well-maintained path consisting of three river crossings and lots of flora and fauna that our guide, Abner, pointed out to us – including aloe leaves, termites that taste like peppermint, and tree bark that you can braid into a rope. This jungle had everything a Mayan kid needs to survive in the wild.

Our kayaks were waiting for us at the river launch, a small opening between two cave tunnels. Water flowed out of one and disappeared into the next. We got in and paddled upstream into the darkness of the river cavern. Quickly, the light of day was gone and we had to rely on our headlamps to navigate. Abner told us that in ancient times the Mayans would carry torches through these caves.

We floated back out and into the entrance of the next cavern, quickly losing daylight again. But we weren’t alone. Tubers were everywhere. I had originally thought to sign up for a tubing trip on this river, but the outfitters who I tried all wanted a two person minimum. So I went with the kayaking trip instead. Turns out that was the right decision, since the guides basically daisy chain all of the tubers together to keep people from floating out of sight. It would have meant that I would have been stuck with a group of strangers, and likely would have been awkward. But in a kayak, I could paddle in my own personal space. I could be a lone cat in a big jungle.

Occasionally the river would pick up and carry us into a riffly channel, but never enough to cause a problem for the novice. It was perfect speed for a scenic river float – never too fast to care about its whitewater rating and never too slow to get bored or restless. Half the fun was trying to navigate around all of the tubers, careful not to hit somebody’s leg with my paddle. We came out of the last and longest tunnel and paddled into daylight under a gorgeous forest canopy. Everything was so much more lush and green – so much more vibrant – than the rivers I’m used to back home. My packraft would be awesome for this.

Soon we reached the river takeout and the trip’s end. Done already? Well, shit. I could eat something and go another three hours easy. But since the tour outfitters work with the cruise lines, they have to get people back to their ships on a schedule. But not before serving us grilled chicken, rice, and beans at a nearby food hall. The national dish of Belize is beans and rice that is boiled in coconut milk. There’s nothing fancy about it but it is delicious.

If I were to come back with a packraft, I would have to skip the cave section since you need a licensed tour guide. But Abner told me that the rest of the river is open. Like if say, I wanted to show up with my inflatable toy and three days of gear for a serious river run in the jungle.