Glacier Discovery by Packraft

It was a sunny weekend in the Anchorage area, and I couldn’t pass up the chance to paddle the cold, charging rivers of Alaska, where the sport of packrafting was born. Just southeast of Anchorage, the Portage and Placer Rivers flow out of the Kenai Mountains to the mouth of the Turnagain Arm, making an easy scenic river trip for the local paddler. These rivers are both train supported, utilizing the Alaska Railroad’s Glacier Discovery line, which will take you within hiking distance of each river launch.

The beginning of each river is the end of a stunning lake, each with its own respective glaciers that carve out of the high mountains, creating a more dynamic lake-to-river boating experience. I wanted to do it all. Because Alaska. I packed my raft, camping gear, and a big box of Pop-Tarts for the weekend and boarded the train on Saturday morning.

Saturday: Spencer Lake and Placer River

9:45am – Depart from Anchorage

1:45pm – Get out at Spencer Whistle Stop, hike 1.3mi to Spencer Lake

2:30pm – Paddle Spencer Lake and Placer River 15mi to highway bridge

6:00pm – Hike 3mi to 20 Mile River and set up camp in the trees

Unlike the other train lines, Glacier Discovery is more specialized to assist in short day trips around the Spencer Glacer, Whittier, and Portage. The train got to the Spencer stop at midday and a group of us got out to raft downstream on commercial boats, kayak on the lake, or hike the trail system.

I hiked out to the edge of the lake, where at some point a glacier calving caused icebergs to float across and beach on the shore. The water was still on the calm day, reflecting the blue face of the Spencer Glacier from across the lake. I suited up and paddled out, maneuvering around several icebergs on the south edge. Soon, I found the river and went for the current. Up ahead, the roar of the rapids made my blood go cold.

It’s always the same. A new rapid is always a daring venture into the unknown to me. My fight against the currents in the river is just as real as the fight going on in my head. Can I get to the bottom of all of this chaos, overcoming the rapid and myself along with it? Will I crash into a mess of rocks and raging water, or will I clear the last standing wave like a rockstar? Go right for the throat, adventurer, with your game face and bright eyes blazing. It will probably work.

I read that these rapids are a fast Class II, and I definitely agreed as I moved around several big rocks. It mostly channeled down the center, so the line was easy. Soon, my fear changed to a familiar afterglow of excitement and relief as I floated out to calming water. I got this… the Placer ain’t got nothing on me.

Up ahead, I saw numerous trees in the river. That’s not good. Wash up against a strainer in water like this and you’re in trouble. Once I got closer, the river started braiding into smaller channels. I realized that the trees were mostly beached on gravel bars, safely away from the water. I figured they would be, seeing as this river is commercially run. I wouldn’t be out here alone if it wasn’t.

For the next hour, I had fun navigating the fast braid system as the river charged its way out of the mountains. Eventually, I floated back into a wide channel, peacefully going out of the valley to the highway and the edge of the Turnagain Arm. I packed up and walked north towards the 20 Mile Bridge.

A few minutes later, somebody saw me walking and offered a ride. It was 3 women from Anchorage who also just got done packrafting the river.

“Hey, I think we saw you up there on the rapids.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah, we put in right after them.”

“Sounds like you guys missed the party!” I wouldn’t blame them, though, especially if they were new to swiftwater. Those rapids looked a lot scarier when I scouted them than they turned out to be. Work your way up to it, erring on the side of caution, and you live to rock another day.

They dropped me off at Portage and got in their cars to go back to Anchorage. Ideally, Portage would be the place to park your car, get on the train, and get out at the top of the river. I set up camp in the trees and slept by the riverside of 20 Mile.

Sunday: Portage River

11:35pm – Get on train at Portage

12:05pm – Get out at Whittier and hike 4mi over Portage Pass

2:30pm – Paddle 3mi to end of Portage Lake

4:00pm – Paddle 8mi on Portage River to Highway

6:00pm – Hike 1mi to Portage Depot

7:20pm – Train to Anchorage

9:30pm – Steak

My Sunday trip was harder, not because of the river, but because of time. I had to traverse 16 miles in 7 hours – only a third of it by foot – to get back to Portage for their last 7:20 stop. I got to Whittier at noon and made a hard pace for the Portage Pass trailhead. From there, the trail was a steep 2 mile scuffle to the lake on the other side.

That lake, let me tell you, was awesome. It was walled in by steep mountains with the crystal blue husk of the Portage Glacier descending out of a snowfield on the far edge. If I wanted, I could have paddled a mile across for a closer look. I made for the river instead, trying to beat the clock.

It was just over 3 miles to the end of the lake and the mouth of the Portage River. That lake was a test of my patience, with unpredictable ripples and wind slowing my progress. Without a current, everything is slow in a packraft. Nonetheless, the vista was amazing, with the giant Portage Glacier standing to my left. And to my right, the huge, steep wall of Mount Mayor towered above the shore. As I passed it, I counted 8 waterfalls cascading down its slopes, a few of them splattering onto the lake. I made it to the far end in the same time it takes to watch Terminator 2, got out, choked down another Pop-Tart, and got going 20 minutes ahead of schedule.

It was great to be back in a current again. The first couple miles were fast, easy Class I riffles, never getting worse than an occasional rock about 20 seconds away. It was definitely the easier of the two rivers, as the fast current flattened out about halfway through. Near the end, the river meandered out of the valley and into slow flatwater – what I like to call a Midwestern Bathtub. The good thing was by that point you’re pretty much done. I packed up at the highway bridge and got to the Portage Depot with 40 minutes to spare.

When the train came, the attendant got out and said “Hey, you made it!” I did, and I felt like a badass.

The Glacier Discovery train makes the shuttle support easy for packrafting – something the paddling scene up there already knows. I ran into 3 groups of people that weekend who were doing the same thing. If you don’t have a packraft, you can still sign up for a guided rafting trip down the Placer River when you buy your train ticket. All supported, all Alaskan.

Those were some great rivers, but I would have to say the highlight of my weekend was the T-bone steak I got at the diner next to my hotel. Only a hard weekend in the Alaskan country could have made it taste that awesome.

This story continues on The Shores of Kodiak Island.

Harpers Ferry by Packraft

Harpers Ferry by Packraft

A lot of things come together in Harpers Ferry. It is the confluence site of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers, the AT and C&O Towpath crossing, three state borders, and one major Amtrak line. And it is the site of a historic Civil War battlefield now owned by the National Park Service. Yet for all its beauty and rich history, the town remains small and quaint, resting on the hillside above the river confluence and old railroad bridges.

After a family visit, my dad dropped me off at the Harpers Ferry Hostel just outside of town. I planned to float the Shenandoah the next day before heading back to Chicago on the train. First though, I wanted to make a scuffle up to the Maryland Heights Overlook for a great view of the town. This marked the end of my summer, and it was a good one. There were adventures to be had, friendships to be made, and obsessions to fulfill. And at the end of it, there was a red sun in the west.

I finally got the wide angle shot of the town that I liked and started packing up when I heard somebody say “Want me to take your picture with the sunset?” It was Megan, a woman from Baltimore on a weekend trip in the mountains. We traded cameras and got our shots, luckily in a 5 minute window before the sun went behind the trees ahead.

We hiked back down the ridge. She told me about a huge road trip she took to the national parks out west, and I told her all about Alaska. At the end of the trail we agreed to stay in touch and I made my way back to the hostel in the dark. If it weren’t for that awesome sunset, we wouldn’t have met. But the trail always has a way of bringing people into my life when I least expect it to.

We hiked back down the ridge. She told me about a huge road trip she took to the national parks out west, and I told her all about Alaska. At the end of the trail we agreed to stay in touch and I made my way back to the hostel in the dark. If it weren’t for that awesome sunset, we wouldn’t have met. But the trail always has a way of bringing people into my life when I least expect it to.

I slept a few hours and left before daybreak for the river. It would be an 8 mile hike to the town of Milville and the public launch to the Shenandoah River. I walked in the dark for an hour before I saw the glow of dawn over the silhouetted mountains. Even then, that early on Sunday morning, plenty of people were driving out on 340.

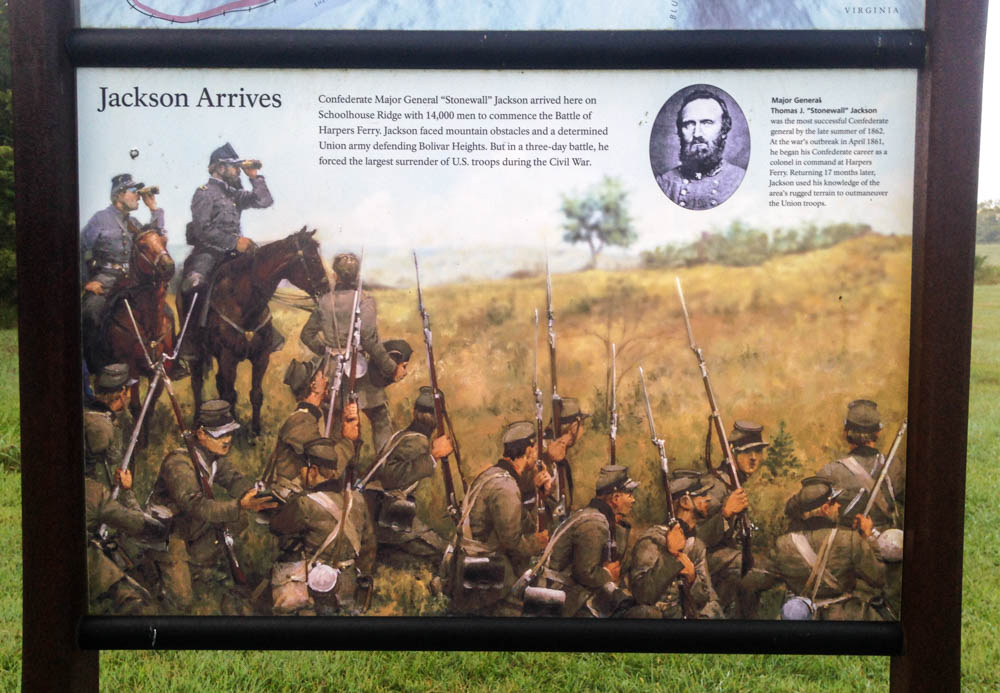

I got to Milville Road at sunrise, just outside of the town. South on Milville Road is the entrance to the Civil War Battlefield. At the top of this field is Schoolhouse Ridge, one of three ridges used by Stonewall Jackson to surround the Union garrison and the town, ultimately leading to their surrender after three days of fighting. This historic site is now owned and operated by the NPS, allowing people to visit and see the features of this battlefield.

Finally, I got to the boat ramp and paddled into calm water at mid-morning. After going for two miles, I hit the first rapid, an unnamed smooth channel going through a small ledge system. After a short break, I got to Bull Falls, the iconic drop on the river. Here, the river channels into a big V-wave, making for an easy line as long as you can bust through the hydraulic at the bottom. I scouted it from the rocks to the right. Further right was another big slot with a nasty log jam. Stay out if you want to live.

I waited for a guided raft to go over the falls and followed behind them. In a packraft, the best way to hit a hole is to lean forward and paddle your ass off. If you do it right, you’ll slam through the glassy water at the bottom and come out clean. Up ahead, the current continued into Bull’s Tail, a fast wave train just after the falls. From there, it calmed down for half a minute and channeled into Lunch Rock Follies, another swift channel that carried me into the middle.

After a big flatwater break, I got into eyeshot of the 340 bridge and the top of Staircase Rapids. As the name would suggest, it is a huge series of small ledges that go down the river for a mile.

It was the end of the summer and the local gauge measured at 1.6ft, making for a bony river run. This made for a lot of scraping as I tried to find runnable channels over each ledge. After a half an hour and a lot of swearing, I finally got to the bottom of the Lower Staircase. The last couple ledges here were good, since the river narrows and brings the channels up enough for halfway decent tongue action. Still, I should have followed a guided raft for it. I hear that Staircase is a sick run in the springtime levels, and I don’t doubt it.

I floated past the town and the stone columns of a torn out railroad bridge to the confluence, where up ahead the Potomac joined the river below the rocky cliffs of Maryland Heights. I passed a group of people on innertubes on my way to Whitehorse Rapid, a solid wave train on river left. Finally, I ferried across to the takeout on the right, ending my last big river trip of the summer.

Thanks to Amtrak’s Capitol Limited line, this town is easily accessible, especially now that it has a bike car. I made a note of it as I boarded to leave. And to make a long story short, I did end up coming back on a bike. But that’s another story.

All packed up and Chicago bound!

Rafting the Lower Yough

Rafting the Lower Yough

I’m always one for an unexpected side trip, especially if the water is fast and the waves are raging. In Appalachia, there’s a lot of it. This time, I was on a bike tour out of Pittsburgh on the Great Allegheny Passage during the latest autumn peak. When I planned my route, I realized that the trail follows the Youghiogheny River past the town of Ohiopyle, a popular area for commercial rafting. So of course I had to sign up for a river trip. To me, a good whitewater hit is like getting a shot of endorphins straight to the jugular. (I would know; I actually gave myself a shot of endorphins right to my jugular, and the feeling could be summed up in two words: Gauley Season)

I made it into town at 10, locked my bike outside, and checked in at Laurel Highlands for their 10:30 trip on the Lower river. Soon, we walked down to the public launch just after Ohiopyle Falls. One of the guides explained all of the safety points to us, like don’t stand in moving water because foot entrapment is definitely not party.

Then they assigned us to our rafts and we pushed out into calm water and the onset of a Class III ledge system. I was put on a 16 footer with a group of 5 nuclear energy workers from North Carolina. They were all part of a team at their jobs, and liked to go on outings together as well, probably because teambuilding.

Our guide steered us into the middle of Entrance Rapid, a meaty Class III with a few really good wave-holes. Thanks to all the rain from earlier that week, the levels spiked that day to about 2ft above average. What would normally be bone city at the end of the warm season was a lot of smooth V-waves and big churning holes. There was plenty of swell and rockout for the river enthusiast. Run a line. Take a swim. Get all out in it. Appalachia.

Cucumber Rapid was next, a big ledge of Class III-IV. We put the drop on it and charged out on the tailwaves and into calming water. A photographer caught us in mid-yell.

This went on for the next mile. In your typical Appalachian style, there was a sweet rapid with a good hit and flipping potential, followed by a break of flatwater and lots of time to gather up your belongings and swim back to the boat. After Railroad Rapid, there is a loop takeout on the right where you can hike back to the top to run the sweet back to back mile again. My packraft would be great for this.

We passed under a bridge and went for two miles of calm water with an occasional riffle. Our guide had an archive of old river jokes, stories and puns to keep us entertained in the down time. I’m sure he’s had plenty of river trips to fine tune his act. He was like a comedian, except that the back of the raft was his stage and we were the audience.

When we took out for lunch, I realized that I was cold. I rented a wetsuit, but realized I probably could have used a spray jacket. Nothing I can do about it now. Maybe I could get my core temperature back with food. That didn’t help. Although shivering in the cool October air on a sweet river trip, I’m pretty sure I’m right to say it’s worth it. I should have brought my drysuit for this.

I felt better again when we got moving. We approached Dimple Rock, a notorious undercut on river left. This one made me nervous. It is the site of numerous fatalities over the last 30 years. The guide had us push hard and steered us into the main line just right of it. It is a wide, easy channel that pillows on the edge of the rock and drops a few feet after. So as long as you don’t fall out at the top then you’re fine. All the rafts got through without incident.

For the next three miles, we went through numerous rocky rapids, pourover holes and ledges, and then more flatwater. Some of them channeled into boulder gardens with multiple lines. But nothing rated higher than a Class IV at a high swell. This wasn’t like the Upper Yough, which is a technical rocky section with a lot of nice Class V in your face. I’d love to shred the gnar out of it sometime.

We got back to the town and I said goodbye to the guide and the nuclear energy team. But not without first buying a set of photos of our trip – our evidence of just how hard this river rocks. I went next door and tried to warm up with food and coffee. It kind of worked, and kind of not really. Soon, I was back on my bike and heading east. Finally, my blood heated up to a good core level as I dried off on the trail.

I recommend Laurel Highlands to anybody looking for a good river trip in southwest Pennsylvania. The river valleys are beautiful and full of sweet whitewater hits. And their guides know the river well, and can bring the good times and bad jokes!

This story continues on the C&O Towpath.

Paddling the Chicago River

Paddling the Chicago River

It is my belief that the best place to see any canyon is from the middle of the river. The urban canyon of the Chicago River is no exception. It goes around the downtown loop for three miles, passing by the tallest and best known skyscrapers in our city. You, traveler, would love the shit out of this.

I finally went down there to paddle it after about 8 months of river withdrawal. I had just got out of PT because I sprained my rotator a couple months ago trying to roll a kayak in a city pool. As much as I try to avoid it, I usually do end up wasting time looking for answers on garbage websites like WebMD. Luckily my shoulder isn’t rotting off like those pseudo-medical clickbait websites want me to think.

But I did end up doing the right thing and got it checked out. I learned some good PT exercises, which I’m still doing to rebuild and strengthen my shoulders and core muscles. Now, the first weekend of May, was a perfect Sunday afternoon. I couldn’t stand it any longer. I had to get out on the water.

I went down to the riverwalk where Urban Kayaks has a launch site along the river. I got in and paddled about three miles past the Drumpf Tower, Wilco Buildings, the infamous Dave Matthews Bridge, Civic Opera House, Sears Tower, and 21 bridges before I finally took out at the public ramp at Chinatown.

The air was warm, lake water was cold, and there was some unpredictable tunnel wind. In a kayak it doesn’t really matter, but in a packraft the wind is either your ally or your nemesis. I fought some bad headwind for the last mile right up to the end. But at least the shoulder didn’t give me any grief. And the scenic buildings towering over my head made everything worth it.

Come out and do it. You can rent from Urban Kayaks at either of their sites at an hourly rate. I’ve rented from them before and they have treated me well. Or if you have your own inflatable toy like I do, they will let you launch it out for $10.

And in case you’re wondering, no, the river isn’t the cleanest one around. The city regularly runs cleanup boats along the river all summer, but you still might see a Coke bottle, cigarette butts, and an occasional tennis ball. This doesn’t stop hordes of people from using the tour boats, kayaks, and riverwalk all summer long. It’s a city river, and it’s what it is.

Just up the street from the riverwalk is all the protein your body needs after a river trip. At the end of the day, nothing tastes better than Da Lobsta’s Surf & Turf Lobster Roll with a hot basket of hush puppies and Sriracha Mayo. Mow it down and thank me later.

Make the river part of your Chicago experience this summer. I’ll be back in August after some past due time in the great north. I’m leaving with my packraft, bike, gear, and shoulders of steel for two months of unfinished business in the boreal country. Onward to Alaska.

Packrafting the Mendenhall River

Packrafting the Mendenhall River

I think I’ve found the partiest day trip: The Mendenhall River in Juneau, Alaska. It is an ideal combination of scenic flatwater paddling in view of majestic mountains, icebergs, and glaciers – with the adrenaline of hard-hitting Class III rapids downstream as the river makes its way to sea.

The lake and river are both in the Mendenhall Valley, which comprises of most of Juneau’s residents. By chance, I was able to catch a tourist shuttle from downtown to the park headquarters along the lake. A short walk from there brought me to the boat launch close to Nugget Falls, a big cascading waterfall that pours down the side of Thunder Mountain and onto the lake.

I blew up the raft, suited up, and paddled towards the waterfall, whose meltwater crashed and roared its way onto the lake’s surface. Up ahead, the blue ice of the Mendenhall Glacier rose above the horizon line, nestled between the hardened slopes of rock. Further above, higher, bigger mountains rose above the arm of the glacier. And somewhere above them, the open plain of the Juneau Icefield reached across for some 50 miles – one of many that exist throughout the Pacific Coastal Range, feeding rivers like the Mendenhall.

As I made my way north, the glacier slowly grew in size until it was a massive blue wall of three stories that spanned shore to shore for 2,000 feet. All was quiet, but my head was racing. This place was fucking awesome.

Should I get any closer? I debated it, but I didn’t know very much about this glacier, or how stable the ice was at the edge. Sooner or later a calving was going to happen. And I wouldn’t want to be close to a house-sized block of ice if it fell off. So I stayed far enough away that it would have been a huge wake at the very worst.

I turned south and spent an hour paddling to the other side past icebergs, all while a more distinguished vista of the glacier and mountains above it became apparent. Before I even realized it, I was getting pulled into the mouth of the river and the onset of some Class I-II rapids, which were fair warmup for the bigger ones downstream.

Earlier that weekend, the glacier had what is called a jökulhlaup – an Icelandic term that describes a sudden break in glacial meltwater from the snowfield higher up. The water then rushes into the glacier’s moulin and eventually reaches the river, causing the levels to spike. It was definitely a few feet above normal, and had already flooded some of the surrounding trails around the lake. This isn’t altogether bad in bigwater like the Mendenhall, which just escalate into fun rollercoaster rapids.

After a few small, riffly sections, I came around a left bend and approached Back Loop Bridge and the start of Pinball Rapid, the big Class III of the day. Other boaters told me there really isn’t any one line through it, and I could pretty much navigate on the spot. So that’s what I did, fighting to keep my boat straight through a barrage of breaking waves. I remember seeing a huge hole to my right as I passed under the bridge and worked my way towards a big wave train on river left. It had more than its share of laterals, one of which almost flipped me.

Further down, the rapids settled as I passed a few surf holes and river bends. The last big rapid pulled me into a wave train on the right. I had to fight to stay clear of the flooded trees along the bank, the only potential hazard I noticed on the run. At the time I didn’t notice, but in the footage I got smacked pretty good by a lateral wave about halfway through.

There’s no better place to truly feel alive than in the middle of wild, crashing water.

To Andrew WK, partying is living. While the term “party” can be used as a noun or verb, it more importantly describes a feeling of ultimate Zen or Being. To me, the middle of a wild river is where I’m feeling my partiest.

I made it through without capsizing, and floated along calm flatwater for a few miles past back yards before taking out at a city trail and walking to the road.

I would recommend the Mendenhall to anybody looking for a fun day trip in the water. If you don’t have your own boat, local outfitters rent kayaks along the lake and offer guided raft trips down the river all summer long. From experience, I would say that either way you do it is very party.

Alone In New Orleans

Alone In New Orleans

I got a fondness for the dirty south, and New Orleans is as dirty as it gets. I went for the first time this season, and confirmed its reputation as a nexus of decadent food, debauchery, and the most deregulated alcohol industry I have ever fucking seen. It was a long time coming, New Orleans. But together we made it count, starting with Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, the oldest bar in North America.

I literally just got out of a cab, checked in at my hostel, and walked five blocks to Lafitte’s to drink something cold and local. The bar was packed with Friday night partiers, but was nonetheless comfortable and friendly. For 293 years, generations of patrons have enjoyed Lafitte’s for its atmosphere and dimly lit interior, creating and telling stories ever since its dodgy beginnings in the hands of a smuggling racket. It is a testimony of the city’s endurance, outlasting citywide fires, hurricanes, prohibition laws, and bullshit. This is not just any watering hole; Lafitte’s is an aged well of handcut stone.

It resides on Bourbon Street, the main arterial line of the French Quarter, blocks away from a notoriously balls-out wild nightlife that resonates for miles. I wasn’t in any mood to party, but I at least wanted to see Bourbon Street in its prime. After a couple beers, I left Lafitte’s to check it out.

It’s not that often that I have a culture shock in my own country, but shit man, this was insane. A full on mile of fucking dudebros, honeys, shiny plastic beads, neon strip bar lights, and loud music, wall to wall, street to street. It was like JMU’s party scene times twenty. It wasn’t even during Mardi Gras, which is even bigger. And still, Bourbon Street was a Mecca of self-indulgence, drawing hordes of partiers every weekend. I felt like I was walking through a carnival solely devoted to debauchery.

But I didn’t come to New Orleans to party (this changed later); I came to New Orleans to eat. It wasn’t hard. In New Orleans, great food is everywhere.

Cajun and Creole Cuisine

Over the weekend, I sought out the best Cajun and Creole cuisines from the shittiest looking places I could find. It turned out to be the easiest thing I did all weekend. I’ve never seen anything like the food scene in New Orleans, which is abundant at every turn. Catfish, alligator, gulf shrimp, pork, spices, you name it. All by people who have done it their whole lives. All local. All awesome.

Some favorites included the Shrimp Poboy from Killer Poboy’s, a small kitchen in the back room of Erin Rose, a cool lowlight establishment of character and ambiance. Seared jumbo shrimp with a sweet slaw of marinated carrots, daikon, cucumber, herbs, and a spread of Sriracha aioli on a fresh baguette. Dat Dog had a great alligator sausage with Cajun mustard and a side of Crawfish Étouffée Fries, which in all honesty tasted like Suicide Girls making out in my mouth. At Mr B’s Bistro, its signature dish kicks hordes of ass: Barbecue shrimp sauteed in Worcestershire-spiked butter sauce with a dash of pepper and Creole seasoning. I devoured the shrimp and got another baguette from the server just so I could finish off the sauce.

Cafe Du Monde was perhaps the most iconic restaurant that I visited. It is famous for its beignets, which they shovel out of their kitchen by the thousands all day long. They served me three pieces of deep fried French doughnuts buried under a heaping pile of sugary crack-powder. They were awesome, even though the line to get inside went for blocks down the street.

Cities of the Dead

My hostel was a short walk from St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, the oldest and best known of NOLA’s “Cities of the Dead”. It is a walled off city block of dilapidated, awesome looking 18th and 19th century mausoleums. I wanted to go on Sunday morning, but thanks to other idiots, they had just closed it off to the public unless you came with a licensed tour guide.

I signed up with Free Tours By Foot, a local nonprofit tour guide service, to check it out the next morning. We met outside of a bar in the Quarter about a mile from the graveyard. The host, Kathy, spent the next 45 minutes slowly walking us there and telling us the history of the French Quarter and the development of the city’s burial process. It short, it is a colorful history of debauchery, crime, infrastructure and sanitation problems, and ultimately a high groundwater table that made it altogether impossible to bury anything, that prompted the people of 18th and 19th century New Orleans to revert to their Spanish and French styles of above-ground burials.

Remains of well-known politicians, architects, and other distinguished people line its graves. Worn by centuries of sun and rain, these tombs bear the scars of early times deep within their cracks of mortar and stone.

Great place, but I had to take off early. I left Kathy a $20 and ran back to my hostel to change into paddling clothes. Some guys from a kayaking company picked me up a few minutes later, and we headed northeast to paddle the swamps around the Pearl River for a few hours.

Swamp Kayaking

New Orleans is surrounded by a huge wetland system of marshes, bayous, meandering rivers, and a network of man-made levees and canals. New Orleans Kayak Swamp Tours is a local outfitter that offers guided kayak trips along one of the bayous near the Pearl River, an hour northeast of the city. By coincidence, the launch point is next to a roadhouse used to film scenes from the first season of True Detective. I had to rewatch the show later recognize the smoky old honky tonk and parking lot that they used to film all of their hard dealings and dangerous people.

We launched and paddled upstream past river shacks for an hour before reaching an open swamp. A layer of mist lay across the bayou, which was devoid of any color, save an occasional early flower or patch of moss on a cypress tree.

It was winter in the bayou country. Gators were in hibernation, bugs were weeks away from hatching, and all was quiet on the water. It was a dismal place where people probably do lose sense of direction and wander endlessly through its channels and dense, foggy overgrowth. And in horror fiction, a dark, rotten hand might come out of the water and take you by the arm. It was where the weak die young and metal lives forever.

We zigzagged around trees and bramble for an hour before turning around and heading back to the bar. We returned using another route, paddling upstream on another channel until we reached the Pearl River. From there, we hooked to the right and came back down a faster channel past a series of abandoned, flooded river shacks before crossing through a slough and stopping at the takeout.

And of course the gas station next door sold hot, freshly smoked Cajun meats, because why the fuck not? By that point, we all had worked up a huge appetite for shrimp, alligator sausage, and motherfucking pork. It’s nothing short of ridiculous how abundant this stuff was. We mowed it down and came back to the city.

Badass Cajun Crawfish

On my last day, I was satisfied in every way but one: I had to find a good local crawfish boil. Some Chicago-based girls who I partied with earlier that weekend on Frenchmen told me about Mississippi River Bottom, a bar and grill just around the corner from all the action on Decatur.

I sat down in their garden early Tuesday afternoon and ordered a pile of crawfish at the market rate of $6 a pound. The cook told me that the tourist restaurants like to charge around double, but they want to keep it local. Fine by me.

I devoured by claw and tail and left a wrecked pile of slaughtered Cajun shellfish as my fondest memory of the dirty south.

It’s settled. I’ve been unvirgined to New Orleans, and she’s a wild one.

Bikerafting the Shenandoah

It was my third weekend to do something adventurous, and I wanted to get in at least one good packrafting trip on a local Virginia river. In my area there are three: the Shenandoah, the Maury, and the James. Having grown up in the same watershed, as both streams from my family’s farm eventually get there, nowhere felt closer to home than the Shenandoah.

I decided to paddle the section between the towns of Elkton and Shenandoah, since both had accessible launch points. At first, I thought I could lock my bike somewhere near the takeout at Shenandoah, drive back to Elkton, float downriver to it, and then ride back. Then I changed my mind, broke the bike down, and strapped it to the bow of my raft along with my day cargo, and brought it with me on the river.

I had done a lot of trips with the bike or the raft, but this was the first time that I combined them. I had seen trip reports of other guys doing this in more remote places, and figured it was time to test the whole bikerafting idea myself. I pushed my bike-heavy raft out into calm water and paddled by a herd of cattle from a nearby farm. It was a bit awkward at first, as everything wasn’t entirely secure, but I managed. I didn’t have a full paddle range and needed to push the bike out further to paddle comfortably. That aside, it was fairly easy to get around in the water. And Alpacka rafts are more than capable of supporting that kind of gear.

As for the river, it was about what I expected. Most of the rivers in the valley are pretty tame, with Class I-II rapids spread out between big stretches of flatwater. The Shenandoah and the James don’t really pick up until they cut through the Blue Ridge Mountains, giving way to bigger Class III rapids and rock gardens. At the end of the summer, the levels were low, and navigating the rapids really had more to do with finding the deepest channels so I wouldn’t scrape over the riverbed. I had to get out a couple times to drag my boat over shallow areas. I went fairly swiftly on a gradient for the first five miles, which was great. The end stretch had a long, boring pool of two miles to the dam at Shenandoah.

I made it to the exit ramp after a couple hours, reassembled my bike, packed up my raft, and rode back to Elkton. Cause after all, I am nothing if not portable.

Packrafts can bring more options to your cycling expedition. Like me, you don’t have to let water stop you. They are rugged enough to get you and your bike across rivers, lakes, and even fjords. And they open up even more options, if like me, you like to run big rivers. You can ride out somewhere remote, stash your bike, and paddle down a whitewater run without the hassle of coordinating shuttles.

The biggest consideration I learned right away was that paddling with my bike and cargo greatly reduces its maneuverability. It is more than capable as a standalone boat in technical swiftwater, but I don’t recommend paddling with your bike and gear on anything higher than Class II rapids.

That, and touring with one will take some trial and error. My packraft and river gear add about ten pounds to my bike cargo, which I hate carrying on my back for very long. The top of the front or back pannier racks would be ideal for storage. Definitely be as ultralight as you can with the rest of your stuff, and keep in mind that a trailer won’t work unless you’re willing to go back and forth over a river, and that’s probably overkill. It may be worth it to ship the raft somewhere ahead of you, as I’ve done before.

Further information on the technique of bikerafting can be found here.

On my way back home, I pulled off the road for some good diner food at Thunderbird Cafe, solely because of the name. It didn’t disappoint.

Return to the New River Gorge

I had unfinished business with the New River. I had been to it once already in my packraft, and never did get to see the whole thing. I remember getting to my launch point for that trip by train, and as I stood between train cars scouting the river, I saw all of the huge Class IV-V rapids of the Lower New River, with countless guided rafts crashing through the turbulent water. It was hypnotic, terrifying, and awesome to watch. And though I was on my way to tamer water that day, I knew I had to come back and paddle it next time.

I got back home a few days later, determined to get back to the Lower River and run it next year.

Last summer, I got my chance. I persuaded my dad to book a reservation at Hawk’s Nest Resort, an old lodge along the east canyon rim a few miles downstream from the rapids (he didn’t need much convincing; he likes the New River Gorge just as much as I). We left on a family weekend trip to the resort, and I borrowed the van on Saturday morning to drive down the road to Ace Raft, the biggest rafting outfitter in the area.

I got registered at the main tent and boarded a shuttle bus to the put-in just downstream from Thurmond, right where I left the gorge last time. I was placed in a group with two couples from North Carolina, and Shanna, a river guide of seven years.

We pushed out into the morning fog and paddled through a few miles of flatwater and a few easy, spread out warmup rapids. Both of the guys had been rafting before, neither of the girls had, and though I knew what to do in a packraft, I had never paddled in a guided twelve footer. Shanna made the most of our time in the calm water and taught us how to paddle as a group.

Our first big run of the day was Surprise Rapid, a Class III a few miles downstream. It is characterized by a big hit at the bottom of the rapid, which at the onset just looks like any normal breaking wave. It’s not until you clear the wave before it that you can see what it actually is – a pourover hole with a huge, churning hydraulic. Any new boater in that rapid won’t know what they have coming.

Shanna did, and steered us right at it. And as mentally prepared as I was, I was not ready to see the horrifying wall of foam that we crashed into, or to hear it roar at us like a beast. I felt like a deer staring into the headlights of an eighteen wheeler. The hydraulic slammed into us, thrashing the boat sideways, throwing me and three other people out.

I tumbled around in the turbulent water and washed into a calming wave train, disoriented, some ten feet away from the boat. After a moment, I got it together and swam back as Shanna scrambled to get the others back in. Soon, we were back on the boat, trying to recover our breath and our minds.

Despite all the theatrics, it wasn’t as bad as it sounds. The hole doesn’t recirculate enough to keep anything for long, and the rapid washes into a big flatwater pool at the bottom. So even though there is plenty of screwup potential, you’ll wind up in calm water eventually. The guides know this, which is why they almost always go through it, or at least try to.

Further downstream, we went through more Class IV-V rapids, many of whom had big hits of their own, like the hole at Upper Railroad. That one sent the boat into the air at 45 degrees. As we approached each section, Shanna would tell us the name of the rapid, it’s whitewater rating, its key features and hazards, and which way to swim if we fall out. I felt like I was beginning to understand how to read and know a river, be mindful of its hazards, and perhaps most importantly, stay cool when I fall into swiftwater.

Soon, the canyon narrowed, bringing us to the wildest section of the Lower River. Here, there are bigger, more technical rapids with smaller flatwater pools between. The most distinct one is probably Double Z. It is aptly named for the line that boaters have to take to navigate around two undercut rocks in the middle, while avoiding more undercuts on the sides. All of the guides got us through without incident.

Thread the Needle was a rad little swimmer’s rapid that we ran near the end of the day. It had two huge boulders in the middle of the river with a small chute between, just big enough for a kayak or a person. A bunch of us jumped in the water and floated through it. I wasn’t in any danger, but it did feel unnerving to go over an eddy line and feel it pull at my feet.

We got back in and finished the day at Fayette Station, a big Class IV wave train with a smooth center line. It glimmered and raged under the towering arc of the New River Gorge Bridge, which stood more than 800 feet above us. The shuttle and a cooler of cold beer were waiting for us at the takeout on river left.

For the entirety of the trip, Ace sends a kayaker out ahead to film the rafts going through all of the big hits on the river. Once back at the lodge, they will take about an hour to edit the footage into a video and burn DVDs to sell at the lodge store. Our camera boater Tigg finished editing our footage, and came back to the main tent where they had TVs set up to play it for us. Everyone was excited to see themselves onscreen, especially my group. Our wipeout at Surprise Rapid turned out to be the money shot of the day.

I don’t have enough good things to say about the New River. I’ve been on it twice now, and both times were amazing.

But this was all just a warmup. I was two weeks approaching the opening weekend of Gauley Season, and that was some serious shit.

Gauley Season

My last weekend in Appalachia was an all out balls to the walls whitewater shitstorm. I rafted West Virginia’s world famous Gauley River, a wild run of Class V rapids back to back, and got everything you could want out of a whitewater rafting trip. Huge wave trains, big ledges, powerful crashing torrents. The Gauley has it all.

Dropping 668ft at an average of 28ft per mile, it runs on a high gradient for 28 miles between the Summersville Dam and its confluence with the New River downstream. In the summer, levels and difficulty can vary, but all of that changes in the fall. Starting every weekend after Labor Day, the Army Corps of Engineers releases the Summersville Dam at a controlled flow of 2,400cfs for six consecutive weekends. The result is a huge series of torrents that cascade voilently through more than 100 rapids between the dam and the confluence below, drawing rafters and kayakers from all over the world.

I discovered it when I was planning my return to the New River Gorge. Commercial outfitters in the area shuttle rafters to both the New and Gauley Rivers, and though the New River is the bigger and more scenic of the two, the Gauley exceeds it sheer technical bone-crushing power. If it were a metal album, it would be the Heartwork-era Carcass of rivers.

There are five Class V rapids on the Upper Gauley, and they have plenty of III-IV rapids between them. Boulders and undercuts can often be seen along the riverbanks, necessitating scouting if you don’t have a guide with you. Its rapids – though iconic and well-known – are not for beginners or for the careless. I knew that guided commercial rafting was the only remotely safe way I could get through them, seeing as my kayak roll still pretty much sucks and I sure as hell wouldn’t try it in my packraft.

I drove out to Ace Raft on the first Friday evening of the season, slept in my parents’ van, and went down early on Saturday morning to the main building to check in. They had us sign release waivers, taught us basic whitewater safety, got us our paddling gear, and boarded us into a Gauley-bound school bus. We reached the put-in at Summersville Dam an hour later, where they organized us into different rafts. I was placed in a group with three other guys and a guide named Bear, a large bearded fellow and experienced riverman. I walked over and greeted him.

“So you just came out here by yourself?” he said.

“Yeah, it’s just me,” I responded.

“That’s wierd. Don’t you have friends you could bring with you?”

“Yeah I do, but they all pussied out!”

We got in the river, which at the onset was pretty cold (wise of me to rent a wetsuit at the lodge), and hit some good III-IV rapids early on as the fear and energy escalated. There were about thirty minutes worth of choppy waves and small holes to contend with as a warmup to Insignificant Rapid, the first Class V of the day. We needed all the time we could get to learn or perhaps relearn the paddling maneuvers needed to navigate this stuff. Fog lay heavily on the river and the roar ahead reminded us increasingly that the flatwater just above Insignificant was deceptively calm.

Soon enough, we were pounding through it. It is more or less a huge wave train with a lot of lateral waves and ledges that go all the way down to the pool below. At the onset, its waves are small and manageable, but become increasingly bigger before passing a huge slanted boulder on the right and pouring into a big hole at the bottom. We rolled right through it and cheered in the flatwater.

It was big, but Pillow Rock was bigger. After thirty minutes or so of negligible, smaller rapids, we floated around a bend to the left and into earshot of what was easily the most dramatic and terrifying rapid of the day. In this section, the river channels into a huge crashing torrent that piles into Pillow Rock, a giant house sized boulder on river left. I knew all about it and remembered it well from my nightmares. My arms and legs were ice cold from adrenaline. Holy fucking shit. This is it!

Sunlight glimmered through the morning fog, and Bear steered us right through the middle of the golden, crashing water. We went right for it as turbulent water tumbled all around us, and Bear shouted “Touch the rock!” We smacked it with our paddles before dropping down another hole and washing out of the rapid. We cheered like we were the kings of the river and high fived our paddles.

Just downstream from Pillow, Hungry Mother Hole was ready to chew us up and spit us out of her huge, foaming jaws. Bear had us ferry in from the left and try to surf the hole. It didn’t work out. The left side of the raft got caught under the current, sending all of us except Bear into the water. In the camera boater’s footage, I can be seen tumbling out and flipping over as my body hit the side of the raft. I came up underneath for a second and kicked my way back to the side. Bear helped two guys back in while I scrambled back into the raft and helped the last guy in from the right.

We continued onto Lost Paddle, the longest Class V section of the river. It has four drops and is loaded with undercut rocks on both sides for most of the way. But nothing that can’t be avoided, as it mostly channels on a center line. We hit the first three drops without any trouble, including the 9ft drop at Hawaii 5-0 Wave, before eddying out to river right and catching our breath. We had one more drop, Tumblehome, the last and most nervewracking section of the rapid. True to its name, it threw us out of our seats, though we all stayed in the boat. Bear yelled at us to keep paddling as we tried to scramble back into position.

Iron Ring was next, a short and sweet little powerhouse of a Class V. It has two 8ft drops, which at dam season levels amount to a huge, beautiful wave train. We hit it head on.

There was one more Class V rapid left. The horizon line slowly vanished ahead as we approached the roar of Sweet’s Falls, the last of the “Big Five” of the Upper Gauley. It is a 14ft waterfall with a small flume right in the middle, giving boaters a smooth line through if they get it just right. A few feet too far right or left will surely mean a dramatic wipeout. Bear steered us smoothly in from the right and we got it by the throat. We hit a small hydraulic at the bottom and back-ferried past the boulders on river left.

Up ahead, we saw an injured kayaker in the water. The camera boater from one of the other outfitters had dislocated his shoulder going over the falls. We paddled up to him, Bear carefully got him into the raft, and we ferried him to shore. Somebody downstream recovered his kayak and he was safely evacuated. All was well again on the river, but it reminded me that you can never be too careful out there. Not even when you know what you’re doing. Bear tied down our raft and we went up to the tents along the banks for a grilled lunch.

Rafting outfitters stop all along the shores of Sweet’s Falls to eat lunch and watch the boaters go over the waterfall. We ate burgers and traded stories with the other groups about where we fell out, which at this point almost everybody had done somewhere.

I came back from the outhouse and saw a raft go over the falls and flip at the bottom, making for some disastrously awesome river carnage. The left side of the raft turned upward from a hydraulic, sending one guy sailing a few feet into the air. The other paddlers tumbled to the right, and half of this newly jettisoned dude landed on the capsizing raft before he tumbled into raging water. Everybody else fell out the other side. People on both riverbanks cheered like they just saw their favorite UFC fighter kick somebody into another timezone. The first thought that came to my mind was HOLY FUCK!!!!! They washed out into calming flatwater and recovered downstream.

After lunch, we got back in and paddled another few miles to the takeout at Wood’s Ferry. Most of the rapids were tamer and more spread out, giving me time to relax and ponder what it all fucking means. By the end of the day, I was certain that my balls had increased in size by at least twenty percent.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Upper Gauley River is the whitewater trip of a lifetime. But as is the case with any big river, you have to know what you’re doing. If you go, I recommend that you do at least one trip on another IV-V as practice, like the Lower New or Lower Gauley rivers. Both of those runs are tamer and more forgiving to swimmers. You should definitely know all of the commonly used paddling maneuvers and absolutely know what to do when you fall out. All that said, it is so worth it.

Bring your game face to this badass river, and take on the finest rapids in Appalachia.

APA Roundup: Packrafting the Flathead North Fork

I have had my packraft for two summers now, and it’s one of the best toys I have. I couldn’t even say how many times I’ve taken it out on the city rivers in Chicago. Whenever I’m not on Google researching ideas for bike tours, I’m doing it for river trips. I have come to find that paddling down a river, a wild one especially, is one of the most engaging ways I can take in the beauty of an outdoor experience. So naturally, I wanted to incorporate it into my Montana trip. Luckily, there were already quite a few people out there who were into the same thing.

Packrafting has already been picking up out west over the last ten years or so, and has developed its own niche in the paddling community. As it grew, the most active among the paddlers joined together and founded the American Packrafting Association in October of 2012. Along with bringing the community together, their focus has been on education, swiftwater safety, wilderness conservation, and river access. Lobby efforts have been done to legalize the sport in Yellowstone, Grand Teton, and Grand Canyon National Parks.

This year, they had their first ever roundup, drawing packrafters from all around for a weekend of paddling, workshops, swiftwater rescue training, and presentations focused on their current river conservation efforts. The organizers booked the weekend at a group site at Big Creek Campground, right along the Flathead North Fork. They planned day trips for everybody on that river and others in the park, depending on a person’s experience level.

I was planning logistics for my tour through Glacier around the same time I got the notice for this event, and when I realized it was right along the way, I added it to my tour dates. I wanted to take my raft on a challenging river again, but knew that running Class II-III whitewater alone was pushing it at my experience level (a lesson I learned the hard way on the New River last year). But I knew that these trips would have a guide and other experienced packrafters who I could learn from.

So I rode my bike to the roundup at Big Creek after hauling my ass over the Sun Road, locked it on a tree, set up camp by the river, and planned to spend the next day on the water. Moe Witschard, the main organizer, let me ship my raft and paddling gear to his house in Bozeman and agreed to take it to the roundup so I wouldn’t have to carry it with me on my bike. Cool guy.

I got up the next morning and unpacked the boat, ready to hit some good splashes on the river with my new friends. The organizers split us up into three groups, based on our experience levels. I was placed in the intermediate group, seeing as I wasn’t completely clueless out there, but certainly didn’t feel ready to run the big stuff with the best of them. Not yet anyway.

Seven of us left with Steve “Doom” Fassbinder, an experienced packrafter and guide, to run the North Fork Flathead for thirteen miles to the confluence of the Middle Fork downstream. It was a big river, about 200ft wide and moving swiftly at a high gradient. Even the calm sections had enough power to pick you up and take you away. Most of the rapids were rated Class II-III with a lot of splashes and wave trains. It was fed primarily by alpine meltwater, giving it a clear jade color.

Our group got our gear together, inflated our rafts, and got in right by the campsite. We pushed out from shore and each went flying down the river. As we went through the calmer sections, Doom taught us some of the basic maneuvers, had us practice self-rescue, and explained how he was able to read a set of rapids and find the right line. We spent the morning paddling through a number of choppy wave trains and turning out frequently to calm eddies along the riverside. But we all had a great time hitting wave after wave. People fell out here and there, but since there weren’t many hazards around and the water was deep, recovery was pretty easy.

Later that morning, Doom had us all eddy out at one point to surf a set of playwaves. Other rafters went out ahead and surfed the waves for a moment before either flipping or washing out of the rapid. I finally got the courage to try it, paddled upstream against the wave train, and then got distracted. Julia was paddling right in front of me when her boat flipped. She went right under my raft, I felt her head hit the bottom. She took a mouthful of water and came up six feet away, yelling for help. I started towards her. She got herself together and yelled “I’m fine! Get my raft!”

I turned around and paddled for it, easily catching a grab loop (and making me wish somebody was around to do this when I wiped out on the New River last year). Got it! …what the hell do I do now?

I was out of the rapids, but still flying down the middle of the river. I couldn’t paddle without letting it go, and it was too big to pull onto my boat.. Shit! Think for fuck’s sake!

I turned back upstream, put it ahead, let it go, and carefully ferried to shore with it bumping against my bow, a technique I came to find out later was called Bulldogging. I got it to a calm eddy and got my feet on the ground. Julia came over a minute later, out of breath and happy to have her boat back. It was my first river rescue. Go team.

We stopped downstream a while later at a shaded outcropping for lunch. Moe’s group caught up with us and we all sat on the riverbank with our colorful boats, trading rafting stories and shooting an array of interesting shit. Many of these guys have been on some amazing expeditions all over the place, and couldn’t bore you if they tried.

Eventually, we went back to our boats and eddied back in to continue the run. I was the the last one to get back in, and the only one who didn’t ferry out far enough to miss a large log sticking out thirty feet down. Luckily, it didn’t have any branches, but it was coming right for my face as I moved right at it in the current. I ducked backwards as it brushed over my bow cargo and nicked my helmet. With the sudden weight on the stern, my bow flipped and I got a face full of cold, dark mountain water. I kicked my way out from under and grabbed the bow line. Before I could think about self-rescue, I went right for a calm eddy, where I kicked to shore and recovered my breath on a rocky outcropping.

The rest of the day went smoothly, as the rapids got more and more peaceful. We finally ended our trip at the Middle Fork confluence, and celebrated with some ice cold beer.

We joined up with the other groups at the campsite that night for a huge cookout with plenty of beer, meat, and good food. Afterwards, a couple of speakers shared their experiences working with legislators and park officials to legalize paddling in various parks, and prevent the use of dams in different river systems. A couple of guys from Tasmania did a presentation on the Franklin River, where packrafters were successfully able to halt a dam construction project and preserve its pristine beauty. It was all really cool, but my exhaustion had finally caught up with me. I had a massively bad splitting headache, and I was feeling tired out from the last weeks worth of nonstop exploring.

I crashed hard and slept harder.

When I got up the next morning, the groups were gearing up for another good day on the water. The beginner level planned to do the same run that my group did yesterday, and my group was preparing to hike somewhere north for several miles and hit a more technical section of the river. I wished them luck and left the campground with my loaded bike, turning southward on a shitty gravel road towards Whitefish.

I hate gravel. My touring bike is durable enough to handle it, but it doesn’t maneuver for shit. And on this road it was even worse because they just poured new gravel on it. I had to go painfully slow, especially downhill, to keep from spinning out and falling sideways. It was two hours that I don’t care to go through again.

Eventually I hit smooth pavement and had an uninterrupted ride all the way to the Whitefish Hostel. I’m sure by that point I had to have smelled like fucking apple blossoms. So I put my bags down, took a gloriously hot shower, and slept like a king for the rest of the afternoon.

I had two days to relax. And unlike my tour, which I planned down to the numbers, there was no agenda. And that’s exactly how I liked it.