Appalachia By Train And Raft

Appalachia By Train And Raft

The Amtrak Cardinal and Capitol Limited lines travel from Chicago to the east coast nearly every day, allowing access to a number of popular, runnable rivers. With a packraft, reaching them is an easy matter of packing up my river gear, riding on a train, and hiking out to a boat launch. On this tour, I combined three different Appalachian river trips into a week-long itinerary of train rides, paddling, and hiking.

Day 1: Packrafting the Potomac

I leave the train at midday and find the riverside trail going west. The river rapids of the Potomac echo through the trees. The afternoon sun is hot and my pack is heavy. I walk for two miles and reach a boat ramp owned by a local tubing outfitter. The guy tells me to stay away from river right. It has collected a lot of debris from flooding and one section of it is sieved out. The reality of this advice, and the collective roar of swiftwater a thousand feet downriver is making me nervous. I’m scared of it. But I can’t look away.

I’m back in Harpers Ferry for the fifth time, setting up to run my packraft on the Potomac River past the town to the 340 takeout downstream. It is a popular Class I-II section of intermittent ledge rapids, drawing a lot of open top kayaks, canoes, duckie boats, innertubes, and every so often some dude with his own green inflatable boat and GoPro that he rigged off of the stern.

I launch out and paddle to the left side, looking for a runnable line through the rocks. Little channels pour every different way and I’m forced to navigate on the spot. I recall seeing a straight current to the right in the satellite view. But since that section isn’t safe, I have to paddle through a boulder garden, often ferrying along ledges to find a way through. My camera keeps going out of position when I go over a wave, because there’s no way to fully tighten the ball joint on my tripod. So I keep having to fix the camera position, which is the most important thing about this trip, because I’m all in it for the Likes.

I paddle fun, bumpy rapids for a quarter mile, then pass the town and the confluence with the Shenandoah. The river widens. I hear another rapid ahead. Again, left is the way through. As I go east, the clouds behind block out the sun and the valley darkens. I need to hurry.

The river channels into Whitehorse Rapid, the only wave train of any notable size. Even so, you could run it in an innertube, fall out, and float harmlessly to the end. I skirt the right edge, ferry to the boat ramp, pack up, and scramble up to the 340 bridge. The hostel sits on a bluff on the other side. It’s my fifth time staying there.

I usually travel alone because I like to do everything on my own terms, but the more extroverted part of me likes to meet people when I do. Which is why I like hostels. They bring adventurous people together in an environment that allows travelers to connect with each other, while at the same time continue on with whatever their thing is. The one in Harpers Ferry is particularly interesting because it hosts a lot AT thru-hikers, cyclists on the C&O, people on roadtrips, and guys like me coming out and doing random shit.

This time I meet a group of 25 people from DC on a cycling meetup. They rode out here on the trails, plan to hike Maryland Heights and go tubing tomorrow, then ride back the day after. When I meet them, I realize this is a demographic of people here that I had never considered: weekend warriors from DC.

I have beers and shots with them as we trade travel stories and river trips. One girl is bringing her kayak to Gauley Fest in two weeks. Another one has questions about Iceland. And another one is a government security employee who wants to get out of it and travel more. So do I. If it were up to me, I would be nomadic and stateless – traveling, taking pictures, making videos, writing stories. But vacations will have to do for now. I finish one more beer with them at a bonfire and go inside to my dorm.

Day 2: Capitol City Layover

I hike back to the town and board the eastbound train in the late morning. Even with my ultralight gear – packraft included – I feel like my pack is weighing me down. I have to get rid of this thing if I’m going to find a brewery. When I get to DC, I check it in with the agent and go outside. Without it, I can walk around instead of hike, if that makes sense.

I load up Google Maps and put in “Brewery”. Twenty minutes later, I’m at Capitol Ale House sitting in front of a colorful flight. Vanessa is texting me something funny. We talk a lot, even though she is in Sweden and I’m in the states. I met her on a trip last year and we have been talking about Sigur Ros over WhatsApp ever since. I send her a link to a B-side from Julianna Barwick, whose angelic voice can melt a heart of stone.

I leave Union Station on the Crescent train for my hometown.

Day 3: The Shenandoah by Packraft

I drive north and park my parents’ van at the Inskeep launch three hours later than I meant to. It takes me 45 minutes to set up the raft and sort my gear. I get moving on the river at 10, losing most of the good hours of the morning. The Shenandoah is mostly calm, opaque and brown from rainstorms washing dirt from the mountain streams. It’s low but has one or two good feet above most of the ledges, often enough for me to get through without looking for a line.

Halfway through the day, I start passing large groups of tubers and kayakers. Why didn’t I think of this in college? I lived in Harrisonburg for years and it never occurred to me that a crew of us could float this river. Complete with outfitters and coolers of beer, we could have been 20 strong. But the truth is, there is a lot of natural beauty in the Blue Ridge Mountains and West Virginia that I took for granted back then. Hell, the AT is 12 miles away from the farm. But that’s why I keep coming back now. I’m making up for lost time.

The day gets hot and I’m running out of energy. It’s my own fault I didn’t start earlier. I have to get focused, because I need to scout the Compton Rapid, considered locally as the boogie rapid of the river. I climb through bramble to get to the riverside and take a look. I can see the line clear as day. You start it on center right to miss a ledge hole on the left, and then work your way left to avoid another one on the bottom right. I easily run it to the bottom.

I take out at Mile 19 and dry my gear in the sun. It’s late in the day and I’m exhausted. I hike the Indian Grave Trail a few miles up the ridgeside and find a flat area to set up camp.

Day 4: The Most Convenient Shuttle Ever

I pack up and keep going up the ridge. To my right I discover a spring and refill my bottles. The trail steepens as the 9am sun shines between the trees, already hot in the morning haze. In its steepest part, this trail is like a staircase of rocks cutting into the mountainside. The sun beats on my face and arms. I see the Shenandoah meandering below the humid backdrop of the Blue Ridge.

I reach the ridgeline of Massanutten Mountain and turn south. On a map you can see it circle around Fort Valley to the west, a small, solitary valley a few miles wide. One road goes through it from 675 to the valley’s end, 20 miles north. Even after all these years it’s the first time I’ve actually seen it.

I go south as the sun rises to an unforgiving angle. There are a lot of exposed rocky areas on the trail that offer little shade. When I do find it, I often stop to catch my breath and bring down my core temperature. I’m supposed to hike 11 miles to the trailhead, but with three full bottles and nowhere to refill on the ridge, I’m starting to have serious doubts if I can ration enough water for this.

What I do know is that Habron Gap is 4 miles from Indian Grave where I started. If it gets too hot, I’ll hike back to the road from there. I spend two hours fighting my way over ridgetops, and eventually get on a steady decline to the gap.

When I reach it, I have to decide. I can ration what I have left for seven more miles to 675, or I can hike down the ridge from here. I realize that even if I do have enough water, I would still be miserable in this heat. I take out my phone and look at the terrain map. Shenandoah River Outfitters is three miles down the mountain. I have to get from the blue dot to the red pin.

I finish my second bottle and start down the Habron Gap Trail. It’s smoother than Indian Grave, with less bramble growing along the sides. It goes steeply down the high ridge for a mile before leveling out in the trees. There, it flattens and I pick up my speed. It’s good to be in woods again.

Fifty yards to my right I hear the rush of a mountain creek. I go over, drink my last bottle, fill up all three, drop tablets into each, and keep going.

Finally, I make it to the road. I hike one last shitty mile to the outfitter and ask the lady where I can refill my water. She says there is a hose around the side of the building.

“Okay. What would you charge to shuttle me back to the Inskeep launch?”

“$30.” DONE. Twenty minutes and two Powerade bottles later, I’m loading up the van and driving out.

Several years ago, I stopped at the Thunderbird Café after another river trip, solely because of the name. I go there again, feeling like this might become a tradition. When I sit at the counter, I drink an extra glass of water. Just because I can.

Day 5: Hometown

The Shenandoah Valley is home. And it doesn’t matter how much time I spend away from it or how much I change, it will always be home. Though I’m too restless to ever move back here, I generally feel like I need to come back about once or twice a year to the quiet town – for the familiar hills, the fireflies, the sunrise on the Blue Ridge, and the sunset over Betsy Bell. Even the Walmart is part of my old life.

I borrow the van and visit my college friend Pete for coffee. We meet up nearly every time I come back. He and Jill had just recently lost their dog of many years and adopted a new puppy in her stead. As somebody who grew up around dogs for half of my life, I get all too well the grief of their loss, and how the joy of a new puppy can heal a family of that sadness.

Pete leaves for work I drive to Gloria’s Pupusaria, because there is no such thing as too much corn masa. Later, my dad drops me off at the Staunton depot, where I once again leave my childhood home for a westbound adventure.

Day 6: Packrafting the Greenbrier

The river is six miles away. I plan to head out of White Sulphur Springs at 4am, determined not to make the same mistakes as before. But first, I eat a fruit breakfast my AirBnB host had prepared for me, and cut slices of the best artisanal cheese bread in the universe.

I hike out on the street in the dark, passing by the entrance to the Greenbrier, a huge world-class resort on the western edge of town, complete with a golf course, casino, spa, lavish weddings, expensive rooms, obscenely rich people, and the one thing I actually am interested in seeing: A decommissioned fallout bunker. The Greenbrier offers tours to their guests and the public to view the resort’s Cold War era fallout shelter, built to protect over 1,100 government officials from a nuclear disaster.

Maybe next time. I would need an extra day and I’m on a schedule. I walk by a parking lot and sit on a rock wall to rest. A security guard is just finishing his graveyard shift and offers me a ride. I load my backpack in his truck and get in the cab. He drops me off close to the interstate exit, a mile from the Caldwell boat ramp. I’ll take it. I get there and start setting up my raft at daybreak, which is the point. But first, I eat the artisanal cheese bread for breakfast. It is everything you ever want bread to be and more.

A canopy of fog hangs over the Greenbrier River and small patches of mist linger above the glassy flatwater. I push out and float into a smooth current. For six miles, I paddle through easy, bumpy Class I sections and the morning brightens. This is a scenic “family float” section of the river from what I can tell. I, however, do not waste my time floating anything, but make a hard pace in the cool morning.

The mid-morning sun breaks through fog and I pass the bridge at Ronconverte. A young fawn stares at me curiously from the river’s edge, perhaps the only eventful thing that happens before the valley narrows into a canyon. We stare at each other as I float by, careful not to spook it off.

The river bends sharply several times below the canyon’s cliffsides, passing from rapids to deep, clear flatwater pools. I think about why I do these kinds of trips. How the energy of a river really does accentuate the beauty of a landscape. When it’s calm, it brings out the peacefulness of the countryside in a way that never quite happens on foot. And when it’s fast and wild, its beauty is amplified through its crashing water and echoing roar across the valley. I never feel truly alive like I do when I’m fighting my way through a wild river rapid to its peaceful end. Because ultimately, the river does what it wants. And I have to enjoy the river on its own terms.

I get out at Fort Spring to eat. I’m two miles from the campground, and two rocky rapids as it turns out. I go around two bends and hear a loud roar ahead. Most of these rapids are small enough for me to eyeball a line, but this one doesn’t have a clear channel from the top. The main channel in the middle goes right into a rock at the bottom. Dammit, I have to get out.

I scout from the left. Sure enough, the center line would be fine if that rock wasn’t waiting to smack into my boat. The far left line right in front of me looks more promising. It’s tight, but I can get it with a quick right turn. I get back in and run through it as planned, but not without scraping the bottom. Good thing my packraft is made for that kind of abuse. I’ve hit rocks with it so many times and have yet to rip a single hole anywhere.

I get to another rapid and try to scout from the top. The current is too fast and I have to improvise. I go for the biggest channel I can find and get stuck on top of a rock just under the current.

Shit! Water is rushing around me on both sides. I lean out and put my paddle in the current, well aware that I don’t want to fall out and chase my raft down this bony ass rapid. Soon I’m freed and go out on the current backwards. I spin around and charge out on the tailwaves, staying clear of more rocks on the right.

This had better be it. Without a doubt, rapids like those are easier at high volume, even if it means bigger waves and higher whitewater grade. But today the river level is rated “Lower Runnable”, requiring more technical lines around the rocks.

I shore in at the campground and set up close to the river. When I go to the office to check in my site, I hear the meow of a kitten from behind the front desk. The lady tells me that it hitched a ride with her to work today. Apparently, the cat climbed through the engine of her car and sat just under the hood that morning. She got in the car and drove to the campground, and when she got out, she heard it meowing from under the hood. When she opened the hood to look, there it was. Not a scratch. Somebody has a guardian angel.

That night, a thunderstorm passes over the valley. I barely notice as the downpour bombards the rainfly on my tent.

Day 7: Take Me Home

The depot in Alderson is five miles away. The river, according to the campground website, has more rapids like the ones from yesterday. I’m reluctant to paddle any further. The last thing I want is to fall out in some bony rapid and hit my leg on a rock. Instead, I pack up and hike on the road.

Stuarts Smokehouse is well known on the river, very largely because they have signs that say things like “Pulled Pork & Brisket at Stuarts, 5 Miles!” I make a strategic three mile hike to get there at 11 when they open for beers and a brisket dinner. Outside, the sign reads “Cold food, warm beer, ugly women.” Sold!

I reach Alderson and wait out the afternoon at the train depot. Several boring hours later, I board the train one last time with my river gear in my backpack.

Later, the golden sun lights the fog gathering at the top of the New River Gorge as #51 passes under the high bridge and out of the canyon. It has a trail system and river of its own – also accessible by the Amtrak Cardinal.

The Prismatica Timelapse

The Prismatica Timelapse

Earlier this spring I created a timelapse video of the interactive Prismatica installation at Navy Pier, Chicago. Design and installation was by Raw Design and Quartier Des Spectacles. If you wish to find out more about their work, you can visit their websites:

rawdesign.ca

quartierdesspectacles.com

This installation is no longer on display in Chicago, but might appear again in another city. When I last checked, they said that the next location is TBD. I hope I see it again somewhere, this project was a lot of fun.

Part 3: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

Part 3: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

…continued from Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

Day 5: The East Fjords

The northeast country was the most diverse terrain I had ever seen. I cleared a ridge in the morning, revealing the vast, open lava fields of the Skútustaðahreppur region. A huge plain of lava rocks and ash spread out across the land. It was everything Iceland is – picturesque, dark, otherworldly, like nothing like I had known. I grew up in a country with millions of acres of deciduous forests, foliage, deer, black bears, and catfish. But here, the calderas, hot springs, snowfields, and glaciers continuously shape the face of the land. It had the openness of Alaska and the emptiness of a lunar landscape. This country was a geologist’s paradise.

There was one particularly rough mountain pass that I cleared at midday to reach the coast. It was graded at 12% downhill on gravel, with switchbacks. The fact that I was still new to driving a manual transmission didn’t exactly help. I swore a lot as I turned at each switchback in a low gear, worried that the van would tumble off the road and roll down the mountainside. But I made it and the road leveled off as I approached the East Fjords, easily one of the most beautiful regions in the entire country.

I drove until mid-afternoon and stopped at the coastal town of Hofn. Natalie reported her status on Facebook. She saw the auroras a few nights ago. I was jealous, even though I had no reason to be.

I left the campground to get a drink at a nearby restaurant. When I looked at their expensive menu, I almost walked out. This restaurant had burgers for $40, a BLT for $40, and entrees going at $60 – prices which unfortunately aren’t that uncommon in Iceland, thanks to their huge tourism industry. But then I saw something better for less: Icelandic pancakes for $12. Now we’re talking.

They brought me a hot pancake with whipped cream, blueberries, syrup, and lots of decadence. I would do it again in a second.

Day 6: Packrafting the Jökulsárlón Lagoon

I figured out that I could stream music from my camper van’s wifi. When I plugged my phone into the dashboard USB, it played the audio through the van’s speaker system. Hell yeah? I wish I figured this out earlier. I loaded up an ambient Spotify playlist and drove the southeast coast to the likes of Hammock, Brian Eno, Caspian, Julianna Barwick, and others who would complement the open road. To me, epic landscapes like these always seems to bring out more depth and nuance in my music. And perhaps the music itself amplifies my sense of adventure as I wander into new lands. I didn’t know it at the time, but as the soundscapes were building and I approached the lagoon, this would be the most exhausting day yet.

I parked at the main lot of the Jökulsárlón Lagoon, a huge glacial lake on the southeast coast. It was one of three lakes that I planned to traverse that day in my packraft. But first, I wanted to see Diamond Beach. The glacier above the lagoon frequently calves, sending huge icebergs across the lake that eventually reach the mouth of a small river close to the road. They break up and wash downstream and into the ocean. The tide then washes them back onto the black sand beach, creating ice diamonds.

I went back to the van, got my gear, and hiked along the east side of the lagoon to find a good launch point relatively clear of the bigger icebergs. The rangers warned me that they could flip anytime, causing a bad accident. I paddled into the lake, far enough from what could have been a dangerous calving.

The Breiðamerkurjökull Glacier to the north was massive. On a map it is about 8 miles wide. There was no way I could fit it into a camera. I paddled across the lake for an hour with that huge glacier to my right and countless icebergs to my left. I got to the other side of the lake, packed up my raft, and started walking the marked trail between there and the lakes to the west.

The trail went over five miles of moraine, but felt like longer. Soon, I was on the higher hills, looking down at the braided streams of glacial meltwater that fed the lake below. The path was defined by trail markers that went on for two good hours before reaching the west end of Breiðárlón Lagoon. I planned to paddle it for a mile to the mouth of a small mile long river on the south end, float the river to Fjallsárlón, and hike back to the road from there. I easily paddled across the lake, luckily without any wind to complicate my route. In a packraft, the wind can take you in any direction it wants, and probably not where you want to go.

I reached the mouth of the river and scouted the rapids at the top. It didn’t look like this on the satellite. I expected to see an easy, floatable river between here and the lake downstream. But this river was fast with a lot of Class II. Well, I’m nothing if not adaptable.

I navigated mostly on center lines through the top rapids. I approached the third rapid about a half mile downstream and positioned for the middle to avoid some holes on the right. I thought I was cruising. Then out of nowhere, I approached a river-wide pourover ledge of four feet. Fuck, I should have scouted it. The swell went over and piled into a big hydraulic. I charged at it, hoping to bust through. No luck! It pulled me back in the hole and I flipped.

Luckily, there was no retention. I washed out of the rapid and went straight into another Class II. Shit, where’s my paddle?!! I spotted it 10 feet away to the left. It was partially submerged with one oar bobbing out of the water. That’s a first. I kicked for it and got it easily. Still pretty unnerving. I waited out another rapid, hoping for an easier break to self-rescue, and got back in just before another rapid was on. As it mellowed out, I scrambled into position and eddied out to the left to get my bearings. I got to the shore and stepped onto firm gravel. That could have gone better.

I love to run big rivers, but wipeouts like that one always freak me out. I wasn’t planning on running swiftwater at all that day. In this case, what looked like an easy float from the satellite was far from it. That said, it can be done if you mind the ledge in the middle to scout and/or portage. I didn’t do either, but I’m sure it has a runnable line.

The satellite said that there were two more rapids before it turned to the right and opened into the lake. I scouted them both and planned on a center line. Pretty much everything on that river was a center line except for that fucking ledge.

I was discouraged, but I kept going. I easily cleared the last few rapids on the river, and went around one last bend. The calming water carried me into the lake in full view of the Vatnajökull Glacier. She smiled back at me as I floated peacefully into quiet water.

I shored in, packed up, hiked back to the road, and eventually got picked up by a traveling German tourist.

This story continues in The Golden Circle.

Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

Part 2: The Ring Road, Rafting the East Glacier River

…continued from Part 1: Jetlag in Reykjavik, Diving the Silfra Fissure

“For all its material advantages, the sedentary life has left us edgy, unfulfilled. Even after 400 generations in villages and cities, we haven’t forgotten. The open road still softly calls, like a nearly forgotten song of childhood.” -Carl Sagan

Day 3: The Ring Road

I think every traveler should drive the Ring Road at least once in their lifetime. As the main highway in Iceland, it circles around almost the entire country, offering some of the most diverse and interesting landscapes you will find anywhere. I had considered the idea of a cycling tour around it, which lots of people were doing, but decided instead to drive its 828 miles in a vehicle.

Lots of people travel to Iceland, rent cars, and go on roadtrips around the country each summer. I didn’t want to stay at expensive hotels and didn’t feel like bringing my camping gear. Instead, I rented a camper van and spent six days driving, exploring, and sleeping. Equipped with a pullout bed, kitchen, stove, table, chair, wifi, and pretty cartoon decals, it had everything I needed to live for the next week.

I loaded my backpacks and suitcase into the van and drove out of the rental agency in the late morning on the beginning of a weeklong roadtrip around the island. But first, I made a stop down the road at the Blue Lagoon, a popular geothermal spa close to the airport.

I’m not much of a spa person, in case you haven’t guessed. But even I could appreciate that lagoon for its natural beauty and decadence. It felt surreal to float in the hot blue water, surrounded by piles of lava rocks. I almost wanted to put some of that exfoliating shit on my face. I didn’t do it, but it also has a fine dining restaurant, island bar, saunas, and massages, if you’re into that sort of thing. Thanks to the island’s geology, there are lots of hot pools like this one in Iceland, though this one definitely gets the most attention.

I got out, dried off in the sun, and drove northward through the city, planning to get to the north country by sundown. The highway in Reykjavik had a lot of roundabouts which were tricky at first to manage on a stickshift. I had just recently learned to drive in manual specifically for this trip. The rental company didn’t have any automatic cars, which I didn’t notice when I made the reservation earlier that summer. So it was either learn on my dad’s farm truck or I don’t get to drive in Iceland. A stressful, yet productive goal.

The road narrowed into two lanes and I left the city behind, going north along the coast on an uncharacteristically sunny late afternoon. I mounted my camera to the windshield to film a timelapse video of the drive. The shutter went back and forth hypnotically for hours as I captured many mountains and towns in the late day.

I turned east, ascending into the hill country, a region quilted in farmlands. I passed countless horse ranches and sheep farms that were almost never fenced in. Sheep wandered freely, sometimes onto the road.

As the evening darkened I drove up another big hill when my camera suddenly stopped. At a glance, the screen revealed “Error 20: A malfunction with the mechanical mechanism has been detected.” What the hell is this? I restarted the camera and turned the shutter interval back on. After a few minutes, it stopped again. I concluded later that night after Googling quite a few message boards that the shutter hardware was starting to wear out and it needed to be serviced. Well, shit. This wasn’t an option on this trip, nor was replacing it in Akureyri for $800. So it meant that I could only get drivelapse shots of the first day. Which was a shame, because this wasn’t even the best part of the road. But luckily, I could still point and shoot, so it was functional enough to be useful.

I arrived at the town of Varmahlíð and turned south on 752. I pulled into the gravel parking lot at Viking Rafting and parked behind the main building, and went inside to ask if I could camp in my van. Eight river guides and support kayakers were sitting on couches and watching an extreme kayaking documentary. I liked them already. After watching a video of two guys dropping treacherously through a slot canyon in California I went back to the van, cooked dinner, and slept. The light faded and the temperature dropped.

Day 4: The East Glacier River

Iceland would have lots of perfectly great, runnable rivers if so many of them weren’t punctuated by dangerous waterfalls. Although they’re great to look at, they’re not so great to attempt in a raft. An exception is the East Glacier River, an awesome Class IV canyon in the north country, where the waterfalls that once existed have been washed out by the continuous pounding of water. It was a river trip full of big hits, fast gradients, sheer lava rock walls, crashing hydraulics, and lots of noise and swearing – exactly the kind of river trip I was looking for.

I was one of three people who signed up to raft on the East Glacier that day, the other two being a newlywed couple from Canada. They had the right idea. If you’re going to honeymoon, you do it right. Do what I do. Go to Iceland, rent a car, bomb a river. We geared up in the main building and left in the shuttle bus for the river launch, 45 minutes on a dirt road from the headquarters. We arrived and sat next to the river while the guide gave us a 30 minute orientation on river safety. He emphasized that we needed to smile and have fun if we fall out to avoid panic – something I in my shortsightedness could have done better. More on that in a minute.

We put on our drysuits, walked the raft to the river, and eddied out into the current. The trip was supported by a kayaking photographer and two rescue kayakers who went out ahead of us in the bigger areas with throw bags and lots of river rescue training. I met support staff from Nepal, Uganda, New Zealand and Alaska – all living and working at the river outfitter for the summer season. Though we were all from different walks of life, there is one thing that always brings we river rats together: We love to run wild rivers.

The entrance rapids were fast and easy as the current rushed through the canyon on a high gradient. We floated past numerous sheer walls in a river 20 feet wide, sometimes less. The first big rapid of the day, Alarm Clock, threw a huge splash my face like a bucket of cold glacier water. We went around sheer bends of rock as the current tumbled its way through numerous Class III wave trains.

Commitment Rapid was next, and was a huge Class IV pourover that flipped the raft and threw all of us out. I felt the current pull my paddle out of my hand, and another rafter caught it as it washed out into the left eddy. Soon we were back in the boat for more. Game on.

After 20 minutes, we eddied out and the guide explained the strategy for Green Room, a technical Class IV triple drop. It turned out to be a monster. We didn’t even get the first drop correctly. The boat flipped again and I was back in the water, flying down the rapid. The current sent me over the second drop. One of the kayakers in the right eddy yelled something at me. I couldn’t hear him. The swell took me over the third drop and into a huge wall of foam.

I expected to wash out of the hole after a few seconds. That didn’t happen. SHIT! IT’S RECIRCULATING!!! I continued to tumble underwater in what felt like an office sized washing machine. Was I stuck in a recirculating hole? What the hell was going on? It felt like an eternity. FUCK!!! I’M NOT COMING UP!!! I need to get out of this now! On other whitewater trips they told me that if I ball up then maybe it will send me back out of the–

I’m out! I can breathe!!! The rescue kayakers were right there, almost like they expected to see me. “Swim to the eddy! Swim to the eddy!” I went for it, but was too tired. They had me grab on the handle on the back of a kayak and ferried me out of the current. The guy snatched something orange out of the water. It was my camera. It fell off somewhere in the middle of all of that shit. He let me go at the eddy and I swam for a rock on the edge. I clung to it as the water pulled at my feet and scrambled ashore – too out of breath to stand, but more alive than I’ve felt in years. Fucking shit, that was crazy.

Turns out I was perfectly fine. That rapid is called the Green Room because if you go far enough into the undertow like I did, you will find yourself surrounded in ambient green light. But without fail, it will eventually spit you out at the surface. I didn’t try it, but the Lower New River has the same feature called the Elevator Shaft. Boaters jump in, get pulled down, and come back up twenty feet away. The casual way the guides joked with me and the other girl who it happened to later was reassuring. I wasn’t really in any danger.

We eddied out to the left to take a break. I heated up my core temperature with hot chocolate and waffles with whipped cream, berry preserves, chocolate syrup, courtesy of a local farmer at the top of the canyon. For years, he has been feeding rafters at this spot. He used to climb down by foot, but at some point rigged a pulley system to lower the food to hungry, cold boaters. Every day. For years. That’s what he has been doing. I can’t even begin to describe how good of karma that is.

Later, we approached a big wave hole and our guide asked us if we wanted to surf it. Usually this causes boaters to fall out, which is often what the outfitters are going after. Because let’s face it, as scary as they get, the river wipeouts do make for the best pictures. I looked at the calm water right after it and thought why not. I already got pummeled upstream anyway, what difference does it make? Sure enough, we got tossed out and easily made for the right eddy.

Jump rock was next, a big 30ft cliff jump near the end of the canyon. I wasn’t intimidated by anything at this point.

The river slowed down and the walls widened, eventually sloping into hills and farmlands with higher mountains far off into the distance. It was calm, easy, scenic, and a great way to end a wild river trip. We packed up and went back to the headquarters where I got a CD burn of the camera boater’s pictures. The Floatie Back Door on my GoPro is the only reason why it wasn’t lost on the riverbed.

I had a few hours of good daylight left. I drove east. I went over a mountain pass, drove past the town of Akureyri, and camped next to Mývatn Lake, one ridge away from the vast lava plains of the northeast. The red sunset brought peace to an otherwise wild second day on the road. So much has happened. But I was just getting started.

This story continues in the fjord country.

Part 1: Jetlag in Reykjavik, Diving the Silfra Fissure

Part 1: Jetlag in Reykjavik, Diving the Silfra Fissure

“I like my backpack, a cup of coffee, and my itinerary, and my passport and I’m out of here.” -Henry Rollins

It was a hot day in Chicago and I was in a dead sprint to get to my bank. I forgot that my debit card had expired and it was the only backup I had if my Visa had any problems. I arrived 15 minutes before they closed and cleaned out my account in cash. I hated to do that but it was the only way I knew of to access those funds over the next ten days. Can I wire it in Iceland? I don’t know. I don’t want to figure that out there. I thought I had prepared for everything, but this put me in a spin.

I got back to my office, hauled my luggage outside, and kept running. It felt like I was in a scene out of Breaking Bad; and I was Walter White, running around like a maniac to close an important deal. Only I wasn’t carrying any blue crystals, just a lot of money that I didn’t want anyone to know about. By the time I got to the airport I was covered in sweat with two backpacks, a large suitcase, and way more cash than I’m comfortable with. When I went through the body scanner, my sweat caused it to throw a flag. I was taken aside for a TSA pat down. Thanks for the extra attention, guys.

Until now, I had only known of Iceland based on what I had seen in pictures and videos. It looked like a vast, magical country where I could keep myself busy for a while. On this trip I planned to be there for ten days and had a loaded itinerary of things to do. The plane disembarked and flew east, leaving the skyline of Chicago and the sunset behind.

Day 1: Jetlag in Reykjavik

When I arrived the next day, it was 7am and my body thought it was 2. I went to the currency exchange and got out my roll of cash to change over to Krona. When the attendant counted it up she asked me if I wanted it back in Icelandic cash or a card. I asked her to explain. She said that she could create a Visa debit account right there with a local Icelandic bank, and I could use that instead of carrying the Krona in my wallet. Fuck yeah, I want my money secured! Thanks, Iceland!

The shuttle bus drove me into the city and I had to wait 6 hours to check into the hostel. It normally wouldn’t be a problem, but I was exhausted from jetlag and felt like canned tuna in a sock. I wondered around uneventfully for the day. The sky was grey and the cold North Atlantic wind almost blew my hat off as I walked down the street for coffee. I finally checked in the hostel at 2:00, immediately crashing in my dorm bed, and then went into downtown to explore. The first place I stopped was the iconic Hallgrímskirkja Cathederal.

This tower was on the top of a hill overlooking the city, now lit up in a perfect sunny afternoon. Weather can change in the blink of an eye in Iceland, but that means that a great day can happen just as quickly as a shitty one.

I went down to the waterfront to see what was there. I found the Sólfarið, or Sun Voyager, a steel sculpture of a boat facing the blue skies to the north. It was built to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the city, and symbolizes the Icelandic ancestors who sailed westward into to the sun to discover new lands.

Natalie, a woman from New York, wanted me to take her picture next to it. Neither of us had any plans, so I invited her to find a bar in downtown. We found a tiny dive next to a tattoo parlor and ordered local beer. She was a theatre choreographer who visited Iceland to run a half marathon tomorrow. Lucky for her, the weather was set to be perfect.

I came back to my hostel and sat in my bunk to read. It took about a minute for me to lose control and start crashing into a deep sleep. I never pass out like that, not even when I’m drunk. But I had a long overnight flight, and an even longer day exploring. And now I felt like I was freefalling into an abyss. Except not really falling, but gently descending backwards into a warm place of fuzzy darkness. Downward is Heavenward.

Day 2: Diving the Silfra Fissure

About an hour northeast of town is the pristine, ethereal Silfra Fissure. It is a flooded trench between the tectonic plates of North America and Europe, where you can literally swim between the continents. The glacial water is near freezing, clear, and perfectly safe to drink. It is beautiful to see and even more magnificent to dive.

I booked my trip for it after watching a few videos from other travelers and learning about its geology. Earlier this summer I spent a weekend getting drysuit certified, and went back to my dive shop in Chicago again to practice in their pool, specifically for this trip. By the time I left for Iceland I was finally ready. The divemasters picked me up that morning and we drove for an hour into the country past numerous mountains, pastures, horse ranches, and eventually the edge of Þingvellir National Park. We reached the flooded canyon at 8, and were the first group to arrive.

They split us into smaller groups, and we suited up and got in at the entrance. When I descended beneath the surface, the drysuit kept me dry and warm, but my face and hands got a rush of cold, not unlike a brain freeze you might get from choking down a milkshake. It didn’t last long. Soon I acclimated to the temperature. We followed our divemaster Marie into the blue canyon, immersed in gorgeous clear water beneath a ceiling of silver. Sunlight danced through the surface, refracting and shining on the rocks in rainbow colors.

At first, my buoyancy was completely off as I tried to maneuver in my drysuit. I found that at different depths it can unexpectedly change. A few times I lost control and went to the surface (it wasn’t deep enough to cause decompression problems). I started getting decent buoyancy control by the middle of the second dive, but it was still a challenge to keep it together as we descended into the blue.

We approached a narrow section where you can literally touch North America and the land between there and Europe, technically about a mile to the east. I swam through this passage and touched the canyon walls between the continents, creating a link between my homeland and that of my ancestors.

On occasion, char fish swim into the Silfra from the warmer lake below. Marie spotted one hiding among the rocks. According to the guides, they taste like something between salmon and trout. Awesome, in other words.

We went to the surface and took a shallow passage over to the next descent. My favorite section was the Cathedral, a trench of 60ft that eventually reaches a sandy slope going up to the grassy shallows on the far end. You can see it from 100ft away, maybe even more. We turned left and entered the Silfra Lagoon, an open shallow area of silt and grass, slowly making our way to the exit platform amidst the sunlit water of the morning.

An hour later, we were driving back to the city. I looked out at the passing mountains, certain that I would remember the Silfra Fissure as a truly remarkable wonder of their country.

This story continues on The Ring Road.

Cave Kayaking in Belize

Cave Kayaking in Belize

I was originally supposed to cycle through the Rockies this summer. I planned an awesome route from Denver that went west over a huge mountain pass of 12,000 feet, and then looped back to Denver over a three day trip. But when I realized that I wouldn’t have much time to acclimate to the elevation change, including one morning of riding from 9,000 to 12,000, I would be putting myself at risk of an altitude injury. It would be one thing if I lived out there, but I’m in Chicago at 600ft. It was a terrible idea, so I scrapped it and went to Belize instead.

Direct flights from Chicago to Belize City can easily go for $600, which is bullshit. Instead, I flew to Cancun for half that much and took an overnight bus across the border, getting into Belize City at 7:30am. The pickup location for the kayaking trip was a mile from the bus station. It was already a hot morning with the sun beating on the side of my face. I had gotten six hours of sleep in the last two days and felt like shit. I didn’t care. I was about to paddle through a river cave, and that’s way important than sleep.

I met the guide at the terminal and we waited for a few other people. Soon, I left on the westbound highway in a shuttle with other Americans on a 60 minute drive into the country. Belize gets a huge number of American tourists – perhaps because it is the only English speaking country in Latin America – and perhaps because its beaches and jungles are amazing places to visit.

We got to the park and geared up for the trip. We hiked on a well-maintained path consisting of three river crossings and lots of flora and fauna that our guide, Abner, pointed out to us – including aloe leaves, termites that taste like peppermint, and tree bark that you can braid into a rope. This jungle had everything a Mayan kid needs to survive in the wild.

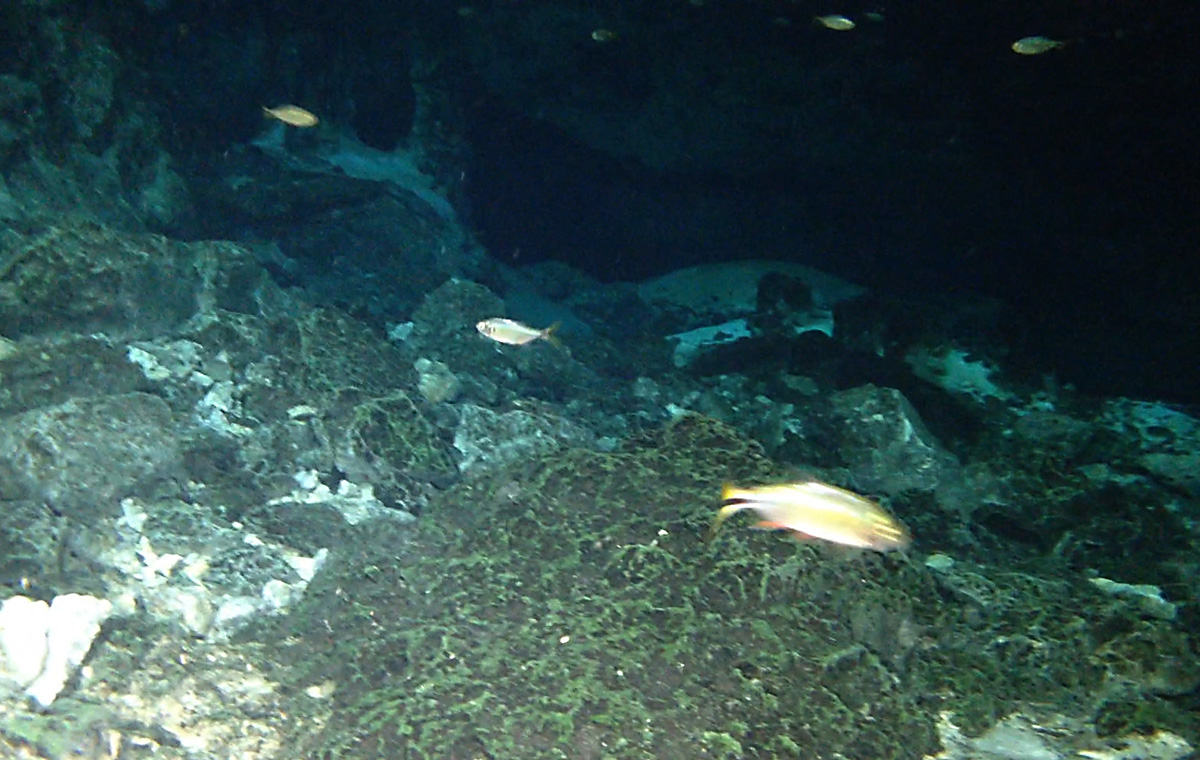

Our kayaks were waiting for us at the river launch, a small opening between two cave tunnels. Water flowed out of one and disappeared into the next. We got in and paddled upstream into the darkness of the river cavern. Quickly, the light of day was gone and we had to rely on our headlamps to navigate. Abner told us that in ancient times the Mayans would carry torches through these caves.

We floated back out and into the entrance of the next cavern, quickly losing daylight again. But we weren’t alone. Tubers were everywhere. I had originally thought to sign up for a tubing trip on this river, but the outfitters who I tried all wanted a two person minimum. So I went with the kayaking trip instead. Turns out that was the right decision, since the guides basically daisy chain all of the tubers together to keep people from floating out of sight. It would have meant that I would have been stuck with a group of strangers, and likely would have been awkward. But in a kayak, I could paddle in my own personal space. I could be a lone cat in a big jungle.

Occasionally the river would pick up and carry us into a riffly channel, but never enough to cause a problem for the novice. It was perfect speed for a scenic river float – never too fast to care about its whitewater rating and never too slow to get bored or restless. Half the fun was trying to navigate around all of the tubers, careful not to hit somebody’s leg with my paddle. We came out of the last and longest tunnel and paddled into daylight under a gorgeous forest canopy. Everything was so much more lush and green – so much more vibrant – than the rivers I’m used to back home. My packraft would be awesome for this.

Soon we reached the river takeout and the trip’s end. Done already? Well, shit. I could eat something and go another three hours easy. But since the tour outfitters work with the cruise lines, they have to get people back to their ships on a schedule. But not before serving us grilled chicken, rice, and beans at a nearby food hall. The national dish of Belize is beans and rice that is boiled in coconut milk. There’s nothing fancy about it but it is delicious.

If I were to come back with a packraft, I would have to skip the cave section since you need a licensed tour guide. But Abner told me that the rest of the river is open. Like if say, I wanted to show up with my inflatable toy and three days of gear for a serious river run in the jungle.

The Dos Ojos Cenotes

The Cenotes of Yucatan Mexico were the sacred wells of the Mayan people, regarded as gateways into the afterlife. To appease their gods, they sacrificed precious artifacts or even themselves into the dark waters of these caves, leaving remains on the cavern floors for many centuries. Today, these pools draw thousands of tourists each day, and serve as windows into an ancient era – a time when they were a source of water and life, and were conversely gateways into a hellish underworld. Just north of Tulum, Dos Ojos, meaning “Two Eyes”, is one such place – aptly describing two cenotes connected by an underwater passage. It is one of Yucatan’s most popular caverns, bringing visitors local and abroad to dive in its pools and underwater chambers.

I, however, would not be diving on this trip. I dove the Tajma-Ha Cenote last year, and though it was amazing, it scared the shit out of me. I don’t regret it, but the truth is that I’m still a beginner. And despite the otherworldly beauty just beneath the surface, I’m not ready yet to risk becoming another statistic in the region’s history of cave diving accidents. Or to appease any of the Mayan gods while I’m at it.

So when I got to Tulum last spring, I walked down the main street and looked for a snorkeling guide. I found an outfitter and told them that I wanted to snorkel at Dos Ojos. They signed me up and told me to come back at 8 the next day. When I did, 8 turned into 9 and I met up with two young guys at a nearby dive shop. They drove me a few miles out to the park entrance. One of them stayed behind while the other guide, Carlos, led me on a short trail to the cave entrance.

I think I’m the kind of adventurer who tends to focus on exploration and I don’t often take time to find out the details of things. I just move from place to place. This is especially true when it comes to the natural history of an area. So it is always interesting to meet people like Carlos, who was the exact opposite. As we walked the path down to the cave entrance, he could tell me the name and history of each tree that we passed. A few times he pointed out a tropical bird somewhere up in the tree canopy that I clearly didn’t have the trained eye to spot.

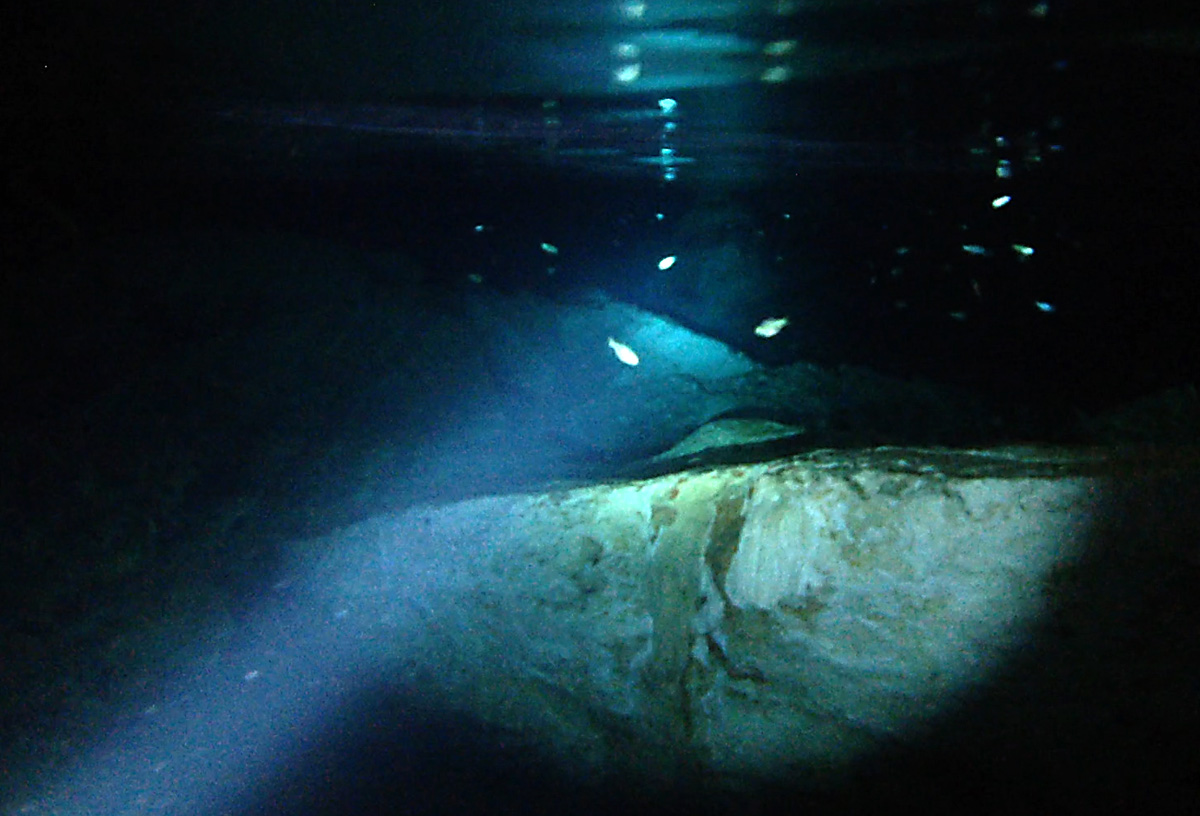

We got to one of the eyes of the caves, and already I was glad to cool off. Little birds nested in the cracks all along the ceiling. Blue water illuminated the ceiling and walls above and below the surface. We swam around the entrance for a few minutes and then Carlos pointed out an underwater passage leading to the other eye of Dos Ojos. We didn’t try it, but I dove down and saw the blue, sunlit opening from 40 feet away – easily doable with a tank.

We passed through a small, winding tunnel into the darkness. It went for thirty feet at the water’s surface and opened into the Bat Cave, a large chamber with a sinkhole in the ceiling and bats nesting everywhere. At night, they fly out in search of food, and at day they rest above the water. When we swam back to the entrance, I saw the dive line and two divers coming out of a chamber 20 feet down, with lights flashing and illuminating the columns and walls of the cavern. It made me want to come back and dive it.

Later, the other guide told me that Dos Ojos has a maximum depth of 8 meters, which is certainly doable. Perhaps I’ll try it again after some more practice in open water. I still have to work out the rough edges when it comes to equalizing, buoyancy, and breathing. Is it safe or wise to have a hobby like this? Probably not. But those caves are too fucking sweet not to try. Or at the very least, snorkel them and freedive into the darkness.

This story continues on The Streets of Centro Havana

Diving MUSA (Underwater Museum of Art)

Diving MUSA (Underwater Museum of Art)

Just offshore from the beaches of Isla Mujeres is an underwater museum of more than 500 sculptures that sit on the ocean floor. Day and night, these gorgeous, ethereal statues lie by the hundreds among the sea life, coral, blue water, drifting sand, and shimmering light. They are MUSA, The Underwater Museum of Art, and they are why I got certified to dive.

I signed up with Aquaworld, a diving outfitter based on Cancun’s hotel strip. They offered two different tours of the museum – one for diving and one for snorkeling. Punta Nizuc is a shallow part of the museum, where at a depth of four meters is only available for snorkeling tours. We departed from the marina at 2 and went south. I drank cerveza on the boat, looking out at the thunderheads in the west. Could they end this tour?

I jumped in the water and followed our guide along numerous turns, as he seemed to know the way. Every few minutes I would look down and see the top of a sculpture amidst the sea grass and schools of fish. We swam right over Reclamation, an angelic sculpture of a woman with her arms raised to the heavens. My camera kept fucking up and I only managed to get one good shot of Understanding, where six men sat around a stone table near the water’s surface.

The next day was more promising. We took the boat out to Manchones, a dive site of eight meters and many more sculptures on the seabed. We got in the water and the other divers disappeared under the surface. As a young diver, I was still uncertain if I knew everything that I kind of learned in my classes. Can I equalize my right ear at this depth? It’s been stubborn before. It turns out that I can. If I start at the top and move my jaw as far as I can to the right, blowing out as I descend, then the air finds its way into my inner ear enough not to fuck up my vacation. And that’s good, because this was only my seventh dive.

We started at the Urban Reef, what would be characterized as an underwater town. There were little one room houses and a few sculptures of bombs and mines on the town’s edge. We swam through Seascape, a vertical ring of eight feet. I followed the other divers as the photographer waited for each of us to swim through.

There were the Bankers, a group of men with suitcases and heads buried in the sand. The divemaster told us that they were originally titled “Politicians” but had to change the name (The joke, I assume, being that politicians and bankers are pretty much the same fucking people.)

But perhaps the most spectacular exhibit of the day was Silent Evolution, a huge crowd of families, adorned already in years of flora. Eventually, they will be just another reef on the seabed. But for now, they watched us quietly as we swam by, marveling at their magnificence.

For the second dive, we explored the ridges of the Manchones Reef, an impressive 12km system along Isla Mujeres. There was abundant coral and sea life, and I was finally starting to get some decent buoyancy. I think I’m ready for deeper places in the sea.

There are many fantastic statues near the surface, but MUSA can only be fully appreciated when you can sit among the men and women of coral and stone. And for that, you have to go 25 feet down.

This story continues in the Dos Ojos Cenotes

The 450 Tour Part 3: The Richardson Highway

Two major highways meet at the junction at Glennallen. It has one gas station, which gets a ton of business in the summer. Most people stop there because there isn’t much else around. There were two bathrooms, and one of them was out of order. So a lot of tourists waited in line to use the other one. I had to use it because I didn’t want to take a dump in the woods earlier that morning (honestly, how often do any of us shit in the woods?), and didn’t know where else to go. Nobody was waiting when I went in, and I tried to go as fast as I could. I came back out to a line of four people. Well, time to get my bike and keep going.

This was the third and final phase of the 450 tour: The Richardson Highway. Here, I would head south along the Copper River Valley for 20 miles, camp out at the Tonsina River, and then take the next day to climb over Thompson Pass. The ride would end in Valdez, where I would stay the night, and then take a Whittier-bound ferry across the Prince William Sound.

I started south. The mid-afternoon sun blazed in the northwest as I rode along the bluffs of the mighty Copper River, looking out when I could at the vast mountains of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. Its peaks range from 12,000 to 18,000 feet, reminding me of the Cascades of the Northwest. Originally, I thought to incorporate a 2-3 day packrafting trip down the Copper River to Cordova, somehow rigging my cycling gear on the raft. When I read that this river has its share of dangerous eddy lines and katabatic wind-driven sandstorms downstream (yes, there is shit like this in Alaska), I decided on the relative safety of the highway instead. But even that wasn’t entirely safe, as I would be flying down a mountain pass tomorrow.

I had one huge hill to clear before a steep descent to the Tonsina River and somewhere quiet to set up my tent. I camped outside of the Russian owned Tonsina River Lodge, fueling up on meat, beer, and caffeine. That night, the 4am sky glowed in what was already a new day in the boreal summer.

I started before the sun came over the mountains. It was supposed to be another hot day on the coast, which doesn’t happen often. I lucked out this summer, as a lot of my outdoor trips ended up having great bluebird weather. Hot as they often were, I would take that over cold rain and fog any day. Though in its own way, I found, the rain and dark clouds can also bring out the richness and magic of the mountain country.

The climb was mostly gradual for 20 miles. The next lodge where I planned to top off my water was closed. I climbed another 5 miles to the next one. Also gone. Fuck, I guess I have to ration what I have over the pass. I didn’t bother bringing my filter, the clogged, worthless piece of deadweight. The road was often steep in places, but manageable. I was surrounded by the huge, steep mountains, with summits carved out by icefalls and glaciers. On any cloudy day, I expected none of this could be seen.

Near the top of Thompson Pass, the Worthington Glacier claws steeply out of a mile high ridge system. I could stop and check it out, or I could worry about refilling my damn water. I had half a bottle left, and was betting on something at the bottom of the other side. There were two more miles to go in the hot alpine sun before reaching the summit. I made it there and looked around the mountaintops, which spread out in a full panorama. Here, the highway descends steeply for 2,600 feet to sea level. I looked at the descending road ahead with a familiar sense of foreboding.

The top of any big bike descent, or river rapid, or scuba dive, always drives me treacherously out of the boredom of my comfort zone and into the thrill of the unknown. I never know what is ahead. And I’m not always confident that I can get through it. But I think my fear is what makes me feel even more connected to the wild outdoors. It could mean hitting a rock at 30mph and crashing on the road. It could mean worse. But despite the risks, I’m drawn to it. This road is horrifying, and horrifying is awesome.

I went flying down the top of the pass for a mile amidst huge green mountains and blue skies. The road went around a loop, and kept going steeply down the mountain. I went fast into the grade and headwind for 10 minutes before I reached the top of Keystone Canyon. Here, the tunnel wind blew through the canyon, forcing me to a crawl. I was out of water, 20 miles from the town, riding along the bends and turns of the canyon. At least the scary part of it was over.

I came around a turn to Bridal Vail Falls, then Horsetail a minute later. The cool moisture got to me. Dammit, I need water! I had left my purifying pills with the rest of my gear in storage, because why would I need them on this tour?

The road turned west towards the town after the canyon, and the headwind was unrelenting. Valdez was 15 miles away. I WANT WATER FOR FUCKS SAKE! Finally, I saw a convenience store across from the airport. I drank a liter of Gatorade and sat outside in the shade, savoring the moment. I am hydrating. Life is good.

No longer feeling weak from thirst, I could enjoy the last few miles of this tour. Numerous ragged sawtooth mountains lined the south end of the valley above the Lowe River and the Valdez Marine Terminal, the big oil port across the bay. Yes, that one. This town was in interesting mix of tourism, local fishermen, and oil industry workers. And on this day, the local DOT was making the most of the hot, dry weather to pave the highway. I saw 5 road crews out, throwing down asphalt as fast as they possibly could.

Finally, I got to the town. I checked in at my hotel and arranged for Nickel to pick me up in Whittier tomorrow. I was exhausted, but not enough not to end this tour with a salmon dinner at the Fat Mermaid by the harbor. A guy with a guitar played Jimmy Buffet covers as I ate and watched the colors of the late day change across the water.

I loaded my bike on the ferry the next morning. It would take six hours to cross the Prince William Sound, but I barely noticed as the boat skirted a million waves along the pristine Alaskan shoreline.

This story continues on the Portage and Placer Rivers.

Glacier Discovery by Packraft

It was a sunny weekend in the Anchorage area, and I couldn’t pass up the chance to paddle the cold, charging rivers of Alaska, where the sport of packrafting was born. Just southeast of Anchorage, the Portage and Placer Rivers flow out of the Kenai Mountains to the mouth of the Turnagain Arm, making an easy scenic river trip for the local paddler. These rivers are both train supported, utilizing the Alaska Railroad’s Glacier Discovery line, which will take you within hiking distance of each river launch.

The beginning of each river is the end of a stunning lake, each with its own respective glaciers that carve out of the high mountains, creating a more dynamic lake-to-river boating experience. I wanted to do it all. Because Alaska. I packed my raft, camping gear, and a big box of Pop-Tarts for the weekend and boarded the train on Saturday morning.

Saturday: Spencer Lake and Placer River

9:45am – Depart from Anchorage

1:45pm – Get out at Spencer Whistle Stop, hike 1.3mi to Spencer Lake

2:30pm – Paddle Spencer Lake and Placer River 15mi to highway bridge

6:00pm – Hike 3mi to 20 Mile River and set up camp in the trees

Unlike the other train lines, Glacier Discovery is more specialized to assist in short day trips around the Spencer Glacer, Whittier, and Portage. The train got to the Spencer stop at midday and a group of us got out to raft downstream on commercial boats, kayak on the lake, or hike the trail system.

I hiked out to the edge of the lake, where at some point a glacier calving caused icebergs to float across and beach on the shore. The water was still on the calm day, reflecting the blue face of the Spencer Glacier from across the lake. I suited up and paddled out, maneuvering around several icebergs on the south edge. Soon, I found the river and went for the current. Up ahead, the roar of the rapids made my blood go cold.

It’s always the same. A new rapid is always a daring venture into the unknown to me. My fight against the currents in the river is just as real as the fight going on in my head. Can I get to the bottom of all of this chaos, overcoming the rapid and myself along with it? Will I crash into a mess of rocks and raging water, or will I clear the last standing wave like a rockstar? Go right for the throat, adventurer, with your game face and bright eyes blazing. It will probably work.

I read that these rapids are a fast Class II, and I definitely agreed as I moved around several big rocks. It mostly channeled down the center, so the line was easy. Soon, my fear changed to a familiar afterglow of excitement and relief as I floated out to calming water. I got this… the Placer ain’t got nothing on me.

Up ahead, I saw numerous trees in the river. That’s not good. Wash up against a strainer in water like this and you’re in trouble. Once I got closer, the river started braiding into smaller channels. I realized that the trees were mostly beached on gravel bars, safely away from the water. I figured they would be, seeing as this river is commercially run. I wouldn’t be out here alone if it wasn’t.

For the next hour, I had fun navigating the fast braid system as the river charged its way out of the mountains. Eventually, I floated back into a wide channel, peacefully going out of the valley to the highway and the edge of the Turnagain Arm. I packed up and walked north towards the 20 Mile Bridge.

A few minutes later, somebody saw me walking and offered a ride. It was 3 women from Anchorage who also just got done packrafting the river.

“Hey, I think we saw you up there on the rapids.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah, we put in right after them.”

“Sounds like you guys missed the party!” I wouldn’t blame them, though, especially if they were new to swiftwater. Those rapids looked a lot scarier when I scouted them than they turned out to be. Work your way up to it, erring on the side of caution, and you live to rock another day.

They dropped me off at Portage and got in their cars to go back to Anchorage. Ideally, Portage would be the place to park your car, get on the train, and get out at the top of the river. I set up camp in the trees and slept by the riverside of 20 Mile.

Sunday: Portage River

11:35pm – Get on train at Portage

12:05pm – Get out at Whittier and hike 4mi over Portage Pass

2:30pm – Paddle 3mi to end of Portage Lake

4:00pm – Paddle 8mi on Portage River to Highway

6:00pm – Hike 1mi to Portage Depot

7:20pm – Train to Anchorage

9:30pm – Steak

My Sunday trip was harder, not because of the river, but because of time. I had to traverse 16 miles in 7 hours – only a third of it by foot – to get back to Portage for their last 7:20 stop. I got to Whittier at noon and made a hard pace for the Portage Pass trailhead. From there, the trail was a steep 2 mile scuffle to the lake on the other side.

That lake, let me tell you, was awesome. It was walled in by steep mountains with the crystal blue husk of the Portage Glacier descending out of a snowfield on the far edge. If I wanted, I could have paddled a mile across for a closer look. I made for the river instead, trying to beat the clock.

It was just over 3 miles to the end of the lake and the mouth of the Portage River. That lake was a test of my patience, with unpredictable ripples and wind slowing my progress. Without a current, everything is slow in a packraft. Nonetheless, the vista was amazing, with the giant Portage Glacier standing to my left. And to my right, the huge, steep wall of Mount Mayor towered above the shore. As I passed it, I counted 8 waterfalls cascading down its slopes, a few of them splattering onto the lake. I made it to the far end in the same time it takes to watch Terminator 2, got out, choked down another Pop-Tart, and got going 20 minutes ahead of schedule.

It was great to be back in a current again. The first couple miles were fast, easy Class I riffles, never getting worse than an occasional rock about 20 seconds away. It was definitely the easier of the two rivers, as the fast current flattened out about halfway through. Near the end, the river meandered out of the valley and into slow flatwater – what I like to call a Midwestern Bathtub. The good thing was by that point you’re pretty much done. I packed up at the highway bridge and got to the Portage Depot with 40 minutes to spare.

When the train came, the attendant got out and said “Hey, you made it!” I did, and I felt like a badass.

The Glacier Discovery train makes the shuttle support easy for packrafting – something the paddling scene up there already knows. I ran into 3 groups of people that weekend who were doing the same thing. If you don’t have a packraft, you can still sign up for a guided rafting trip down the Placer River when you buy your train ticket. All supported, all Alaskan.

Those were some great rivers, but I would have to say the highlight of my weekend was the T-bone steak I got at the diner next to my hotel. Only a hard weekend in the Alaskan country could have made it taste that awesome.

This story continues on The Shores of Kodiak Island.