Harpers Ferry by Packraft

Harpers Ferry by Packraft

A lot of things come together in Harpers Ferry. It is the confluence site of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers, the AT and C&O Towpath crossing, three state borders, and one major Amtrak line. And it is the site of a historic Civil War battlefield now owned by the National Park Service. Yet for all its beauty and rich history, the town remains small and quaint, resting on the hillside above the river confluence and old railroad bridges.

After a family visit, my dad dropped me off at the Harpers Ferry Hostel just outside of town. I planned to float the Shenandoah the next day before heading back to Chicago on the train. First though, I wanted to make a scuffle up to the Maryland Heights Overlook for a great view of the town. This marked the end of my summer, and it was a good one. There were adventures to be had, friendships to be made, and obsessions to fulfill. And at the end of it, there was a red sun in the west.

I finally got the wide angle shot of the town that I liked and started packing up when I heard somebody say “Want me to take your picture with the sunset?” It was Megan, a woman from Baltimore on a weekend trip in the mountains. We traded cameras and got our shots, luckily in a 5 minute window before the sun went behind the trees ahead.

We hiked back down the ridge. She told me about a huge road trip she took to the national parks out west, and I told her all about Alaska. At the end of the trail we agreed to stay in touch and I made my way back to the hostel in the dark. If it weren’t for that awesome sunset, we wouldn’t have met. But the trail always has a way of bringing people into my life when I least expect it to.

We hiked back down the ridge. She told me about a huge road trip she took to the national parks out west, and I told her all about Alaska. At the end of the trail we agreed to stay in touch and I made my way back to the hostel in the dark. If it weren’t for that awesome sunset, we wouldn’t have met. But the trail always has a way of bringing people into my life when I least expect it to.

I slept a few hours and left before daybreak for the river. It would be an 8 mile hike to the town of Milville and the public launch to the Shenandoah River. I walked in the dark for an hour before I saw the glow of dawn over the silhouetted mountains. Even then, that early on Sunday morning, plenty of people were driving out on 340.

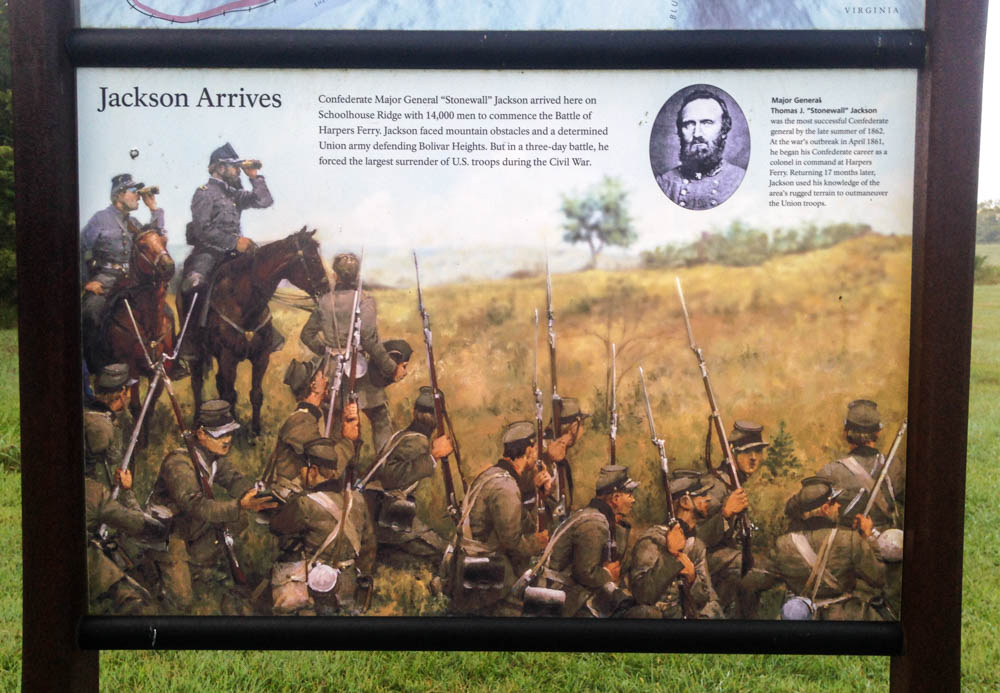

I got to Milville Road at sunrise, just outside of the town. South on Milville Road is the entrance to the Civil War Battlefield. At the top of this field is Schoolhouse Ridge, one of three ridges used by Stonewall Jackson to surround the Union garrison and the town, ultimately leading to their surrender after three days of fighting. This historic site is now owned and operated by the NPS, allowing people to visit and see the features of this battlefield.

Finally, I got to the boat ramp and paddled into calm water at mid-morning. After going for two miles, I hit the first rapid, an unnamed smooth channel going through a small ledge system. After a short break, I got to Bull Falls, the iconic drop on the river. Here, the river channels into a big V-wave, making for an easy line as long as you can bust through the hydraulic at the bottom. I scouted it from the rocks to the right. Further right was another big slot with a nasty log jam. Stay out if you want to live.

I waited for a guided raft to go over the falls and followed behind them. In a packraft, the best way to hit a hole is to lean forward and paddle your ass off. If you do it right, you’ll slam through the glassy water at the bottom and come out clean. Up ahead, the current continued into Bull’s Tail, a fast wave train just after the falls. From there, it calmed down for half a minute and channeled into Lunch Rock Follies, another swift channel that carried me into the middle.

After a big flatwater break, I got into eyeshot of the 340 bridge and the top of Staircase Rapids. As the name would suggest, it is a huge series of small ledges that go down the river for a mile.

It was the end of the summer and the local gauge measured at 1.6ft, making for a bony river run. This made for a lot of scraping as I tried to find runnable channels over each ledge. After a half an hour and a lot of swearing, I finally got to the bottom of the Lower Staircase. The last couple ledges here were good, since the river narrows and brings the channels up enough for halfway decent tongue action. Still, I should have followed a guided raft for it. I hear that Staircase is a sick run in the springtime levels, and I don’t doubt it.

I floated past the town and the stone columns of a torn out railroad bridge to the confluence, where up ahead the Potomac joined the river below the rocky cliffs of Maryland Heights. I passed a group of people on innertubes on my way to Whitehorse Rapid, a solid wave train on river left. Finally, I ferried across to the takeout on the right, ending my last big river trip of the summer.

Thanks to Amtrak’s Capitol Limited line, this town is easily accessible, especially now that it has a bike car. I made a note of it as I boarded to leave. And to make a long story short, I did end up coming back on a bike. But that’s another story.

All packed up and Chicago bound!

Rafting the Lower Yough

Rafting the Lower Yough

I’m always one for an unexpected side trip, especially if the water is fast and the waves are raging. In Appalachia, there’s a lot of it. This time, I was on a bike tour out of Pittsburgh on the Great Allegheny Passage during the latest autumn peak. When I planned my route, I realized that the trail follows the Youghiogheny River past the town of Ohiopyle, a popular area for commercial rafting. So of course I had to sign up for a river trip. To me, a good whitewater hit is like getting a shot of endorphins straight to the jugular. (I would know; I actually gave myself a shot of endorphins right to my jugular, and the feeling could be summed up in two words: Gauley Season)

I made it into town at 10, locked my bike outside, and checked in at Laurel Highlands for their 10:30 trip on the Lower river. Soon, we walked down to the public launch just after Ohiopyle Falls. One of the guides explained all of the safety points to us, like don’t stand in moving water because foot entrapment is definitely not party.

Then they assigned us to our rafts and we pushed out into calm water and the onset of a Class III ledge system. I was put on a 16 footer with a group of 5 nuclear energy workers from North Carolina. They were all part of a team at their jobs, and liked to go on outings together as well, probably because teambuilding.

Our guide steered us into the middle of Entrance Rapid, a meaty Class III with a few really good wave-holes. Thanks to all the rain from earlier that week, the levels spiked that day to about 2ft above average. What would normally be bone city at the end of the warm season was a lot of smooth V-waves and big churning holes. There was plenty of swell and rockout for the river enthusiast. Run a line. Take a swim. Get all out in it. Appalachia.

Cucumber Rapid was next, a big ledge of Class III-IV. We put the drop on it and charged out on the tailwaves and into calming water. A photographer caught us in mid-yell.

This went on for the next mile. In your typical Appalachian style, there was a sweet rapid with a good hit and flipping potential, followed by a break of flatwater and lots of time to gather up your belongings and swim back to the boat. After Railroad Rapid, there is a loop takeout on the right where you can hike back to the top to run the sweet back to back mile again. My packraft would be great for this.

We passed under a bridge and went for two miles of calm water with an occasional riffle. Our guide had an archive of old river jokes, stories and puns to keep us entertained in the down time. I’m sure he’s had plenty of river trips to fine tune his act. He was like a comedian, except that the back of the raft was his stage and we were the audience.

When we took out for lunch, I realized that I was cold. I rented a wetsuit, but realized I probably could have used a spray jacket. Nothing I can do about it now. Maybe I could get my core temperature back with food. That didn’t help. Although shivering in the cool October air on a sweet river trip, I’m pretty sure I’m right to say it’s worth it. I should have brought my drysuit for this.

I felt better again when we got moving. We approached Dimple Rock, a notorious undercut on river left. This one made me nervous. It is the site of numerous fatalities over the last 30 years. The guide had us push hard and steered us into the main line just right of it. It is a wide, easy channel that pillows on the edge of the rock and drops a few feet after. So as long as you don’t fall out at the top then you’re fine. All the rafts got through without incident.

For the next three miles, we went through numerous rocky rapids, pourover holes and ledges, and then more flatwater. Some of them channeled into boulder gardens with multiple lines. But nothing rated higher than a Class IV at a high swell. This wasn’t like the Upper Yough, which is a technical rocky section with a lot of nice Class V in your face. I’d love to shred the gnar out of it sometime.

We got back to the town and I said goodbye to the guide and the nuclear energy team. But not without first buying a set of photos of our trip – our evidence of just how hard this river rocks. I went next door and tried to warm up with food and coffee. It kind of worked, and kind of not really. Soon, I was back on my bike and heading east. Finally, my blood heated up to a good core level as I dried off on the trail.

I recommend Laurel Highlands to anybody looking for a good river trip in southwest Pennsylvania. The river valleys are beautiful and full of sweet whitewater hits. And their guides know the river well, and can bring the good times and bad jokes!

This story continues on the C&O Towpath.

Flightseeing Denali with K2 Aviation

Denali National Park from the sky. This was like nothing I had ever seen. I went on a flightseeing trip over the majestic snowcapped mountains of the Alaska Range. And only from the air, I learned, do you truly feel the immensity and scale of the high places of the world.

It was mid-morning and my last day in Talkeetna. I signed up for the earliest flightseeing trip out with K2 Aviation, hoping the beat the low pressure system that was in the forecast later that day. The last few days have been clear, but this might be the last window I had before the mountains were once again shrouded in clouds and blizzards.

The pilot, Mike, greeted us at the airstrip, gave us a brief orientation, told us where the survival gear was on the plane, and had us board a small red 10 passenger plane next to the runway. We each put on headsets, and soon the plane lifted off of the ground. The trees below became a huge green carpet as we flew northwest across the silver braids of the Susitna. Up ahead, the high mountains slowly closed in.

Soon, the spires of the Tokosha mountains were directly below us, split by glaciers and icefalls. We flew across the huge arms of the Tokositna and Ruth Glaciers and into the Great Gorge, a section of the Ruth Glacier boasting granite walls of 4,000ft of sheer relief. Up ahead, Denali, Mount Hunter and Mount Foraker slowly approached under a thin band of cirrus overcast.

Mike named off each mountain and glacier and we asked him questions with our headsets. He pointed out the Kahiltna Basecamp far below, where mountaineers were gearing up for the first stage of a Denali summit. Numerous tents and people could be seen dotting the white blanket of the glacier.

We circled back and made for the Ruth Amphitheatre, a large snow covered section of the upper Ruth Glacier, and a popular landing site for the flightseeing trips. When I got out, the panorama was fantastic. High, ragged mountains, ice and snow surrounded us as we walked around the plane taking pictures. All while plane after plane landed and took off from the makeshift runways.

As we flew out, the lower Ruth Glacier was laden with thousands of crevasses, like the scales of a giant fish. I asked Mike how far down they can go. He said they can often be up to 200 feet deep. This was a wonderful, hostile wilderness that ultimately must be respected and remembered.

Soon, I was back in Talkeetna getting food and boarding the southbound train for another adventure. Whether by ground or by air, my two week visit to Denali National Park was the trip of a lifetime.

This story continues on the Seward Highway.

The Alpenglow of Denali

The Alpenglow of Denali

“To the lover of wilderness, Alaska is one of the most wonderful countries in the world.” – John Muir

This was it. Denali, the park that changed my life forever. I obsessed over Alaska for four years because of that incredible mountain. I saw it for the first time in 2012, two days after the summer solstice. I remember cycling on the park road all night under the twilight of the Alaskan summer, easily the most backbreaking ride I’ve ever done. I climbed over hill after hill, hours beyond my threshold of exhaustion. I was getting schooled on what it is like to go beyond wherever your limits are, only to find out that you’re not even close to your goal. Finally, I cleared one last big hill to the first overlook, and saw Denali thundering into the morning sky, five times as high as I remembered in my dreams. It shattered my whole world. But little did I know that it would make me into what I am today: A traveler.

Since that trip, I have traveled as often as possible by train, foot, bicycle, or raft. And I’ve seen a lot of amazing places. But nearly every day for years, Alaska was on my mind. It was time to come back and finish what I started.

The first place to go on my trip back was Wonder Lake, a scenic area at Mile 85 of the park road. It is about twenty miles further than where I ended my trip last time. I originally planned to see it then, but was way too fucking exhausted to go any further than the Eielson center that day.

I boarded a Denali-bound train from Anchorage on a cloudy Saturday morning, got to the park in the afternoon, and camped at Riley Creek, a large campground by the welcome center. Early the next morning, I loaded my bike and gear on a shuttle bus for the Wonder Lake Campground, where I planned to spend up to a week waiting out the clouds, which more often than not will cover over the mountains. But if luck will have it, the mountains will eventually clear, giving me the pictures I had hoped to get four years ago. The north face of Denali and the majesty of the Alaska Range above a large open plain of forests, lakes, and rivers. This time I would get it – this time with better gear and experience.

The shuttle was full of backpackers who planned for days or weeks of hiking in the backcountry. As the bus went along the turns of the outer range, sheets of clouds and rain bombarded the mountains, clearing just long enough to reveal a fresh dusting on the high ridges. Occasionally, the driver stopped to point out moose our caribou walking through the tundra fields. I hadn’t yet adapted to the time change, and my caffeine addiction was killing me.

After a few hours, the rain backed off to occasional breaks of sun between the dark clouds. We got to the Wonder Lake Campground in the early afternoon, which sits on a hillside of tundra facing the Alaska Range, 20 miles to the south. I managed to find a campsite and set up about an hour before the next shower. From there, I waited out the bad weather for better fortune.

I hiked for a few hours on the McKinley River Bar Trail to the edge of the McKinley, a huge braided river that flows out from the north side of the range. The trail starts through about a mile of tundra, stream crossings, and kettle ponds before going through a dense taiga forest, and then stopping abruptly at a rushing channel of the river. From here, people who want to hike the further reaches of the backcountry will scout out the McKinley’s elaborate braid system and ford the shallowest channels they can find. Instead, I went back.

Later that evening, a ranger gave a presentation at the small amphitheater next to the campground. The life of a park ranger in Denali. He summarized the history of the NPS and the park, and told us what it was like to live out there every summer. Behind him, the evening sun lit up the forests under dark summer clouds, which still blocked the high mountains. That night, I slept under scattered showers.

I finally got my break the next morning. The clouds started clearing up, revealing the curves of Wickersham Wall against the blue sky. Soon, Denali and the sister mountains were in the clear, standing high above the countryside in resounding glory. The evening sun descended slowly in the north, casting alpenglow on the high mountains.

It was game time. I am going to timelapse the shit out of this. I got on my bike with my camera gear and rode a few miles out to Reflection Pond, a classic vantage point where many a famous picture of Denali has been taken and remembered. I set up my camera across the pond, programming the shutter to hit every 5 seconds as the orange glow of sunset left the mountain. Slowly, it blended from orange to pink, to lavender, to pastel blue, and then finally bright colors again in the early morning. All while a solitary duck swam around the pond. All while the park slept under the twilight of the summer night. All while my camera clicked away, burning, forever burning the landscape into memory.

At about 5, I took my camera to a hill next to Wonder Lake, another famous overlook a few miles away. By now, the Alaska Range was blazing in white under a crisp blue sky, and the park was waking up from one of the shortest nights of the year. The sun crested over the hills to my left, slowly casting light onto the trees ahead, while ripples of wind blurred the glassy lake below. This moment was every bit as glorious as I had hoped it to be. There’s not enough breath in a lifetime to fill that sky.

I loaded my bike on a shuttle bus a few hours later and rode 25 miles up the park road to Stony Hill. I spent the next few hours flying back out of the range and onto the open plain towards the campground, curving around the hills of the tundra fields. This was my favorite part of the park. While pretty much any mountain in that park could be its own postcard, the panorama here was by far the most dramatic. The outer range to the east, the Muldrow Glacier and Alaska Range to the south, and more kettle ponds and waterfowl than you could even begin to count. I was all out in it. It was so fucking awesome.

I got what I wanted. Finally, after all this trouble. Denali, the crown jewel of Alaska, in a rare moment of clarity. For the longest time, this was the holy grail of my whole traveling world. And I got it, finally, after four years of wanderlust. So when I got back to my campsite that afternoon, something unexpected happened. I wanted to leave.

How was that possible after everything I had put into this? I think some of it was definitely the fact that I felt like shit for lack of sleep. I was also starting to miss the comfort of showers, laundry, internet, red meat, and beer. I was getting sick of my backpacking food, and liked the mosquitoes even less.

But I think the bigger thing was that I felt like I saw everything that I came there to see. It was sort of like going to an art museum and eventually getting tired of looking at really cool art for two hours. Well, I guess I was tired of looking at Denali for hours and hours, as hard as that was to believe. Wonder Lake was every glorious thing that people had to say about it, but I was done. I took a bus back to the headquarters early the next morning and camped for the remaining days in the shade and comfort of Riley Creek. As soon as I got back, I went straight for the park restaurant for a burger of champions.

Riley Creek is a large campground in the shade of the forest, which was exactly what I wanted on a hot day like that one. That afternoon, I was in the middle of sorting out my gear when I heard a voice behind me: “Hey, you want to see a moose?” It was Allison, a woman from North Carolina who was visiting the park for a few days before a business trip to Anchorage. I agreed, and we quietly snuck 30 feet away from a female laying down in the trees. A minute later, its calf walked up to it, and they both wandered off. They continued to hang around the campsite for days, much to the curiosity and worry of the visitors, probably because the mother knew that predators tend not to be a problem at loud campgrounds. Moose are usually irritable and dangerous, but they seemed to know that the people around didn’t want to bother them.

Allison and I left early the next day to hike up to the Mount Healy overlook, which is a sharp 1700ft gain up the mountainside right next to the headquarters. It was a steep, exhausting climb up the face of the mountain and took hours. But we finally managed to scramble onto a bare, rocky outcropping and see a great view of the Nenana River Valley. To the right, the ridge system went on for 10 miles before it would slope downward to the Savage River. The very top of Denali could be seen above the mountains to the west, only a few hours before it would hide in the clouds again. The haze of wildfire smoke blew in from the valley to the east. Down below, the thin strip of the Parks Highway followed along the glimmering Nenana River.

We made our way back down the mountain, got lunch at the park restaurant, and Allison left on a tour shuttle bus to see the park road. I went back to camp. And for the first time in weeks, I did nothing.

The next day was our last one in the park, and we agreed on one last vitally important thing to see: The Sled Dog Demo.

These dogs are a very big part of the work that goes into maintaining the park. In the winter, rangers use them to access areas of the park where vehicles obviously can’t get to. They grow and train the dogs at the kennels close to the main headquarters and take them out on practice runs all summer long.

Three times each day, they have sled dog demonstrations, where a ranger comes out to tell large groups of visitors about the dogs and their history and use at the park. Then they bring out one of the sleds and have some of the dogs run a loop right in front of the audience. Whenever they do this, the dogs go completely nuts.

And finally, everybody goes over to the kennels to take pictures and pet the dogs. The rangers believe that socialization is a very important part of their training, and encourage tourists to visit and pet them. Cause after all, a social dog is a happy dog.

Allison and I agreed that it was a motherlode of cute. I mean look at those guys. They redefine badass. It was a good final note to end this chapter of our adventures. Soon, we boarded the southbound rail and shared a seat in one of the dome cars. Her exhaustion finally got the best of her and she passed out in the seat. I continued to watch the forests and mountains go by.

I got out at Talkeetna and she continued on her journey southward. The train rumbled and faded into the distance and all was quiet at the depot. I wasn’t done with Denali yet. I got on my bike and made for the hostel.

This story continues in the South Foothills.

Los Cenotes en la Riviera Maya

Los Cenotes en la Riviera Maya

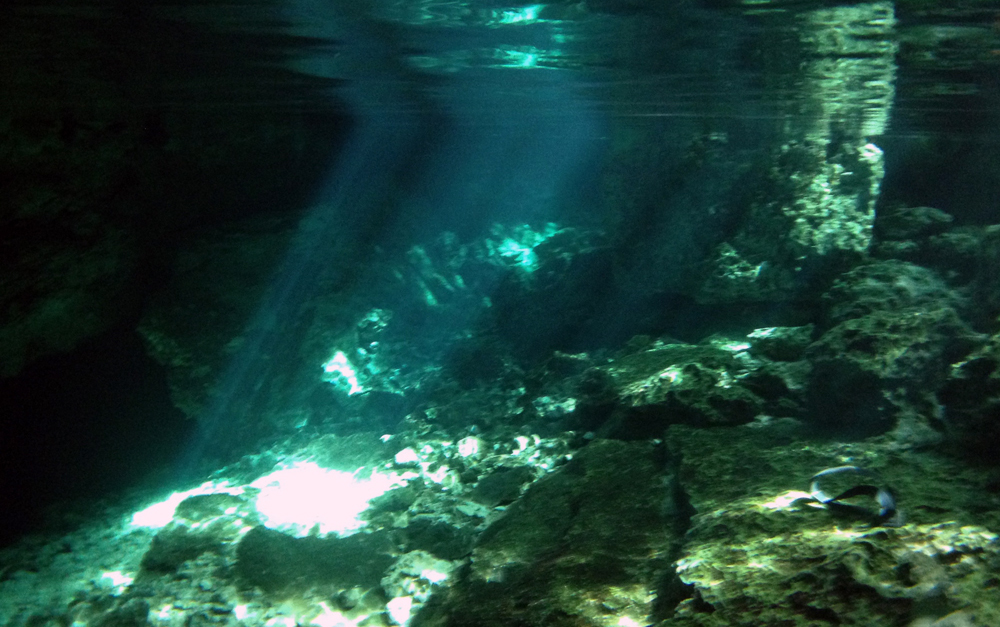

If you have seen Planet Earth as many times as I have, then you would know about the Cenotes, the huge network of flooded underground caverns that flow beneath the jungles of the Yucatan. Many exist throughout the region, caused by collapsed cave ceilings that create sinkholes and gateways into a magical and largely uncharted underwater world. The water is clear and illuminates in shades of turquoise and sapphire, caused by rainwater slowly filtering its way through the limestone bedrock above. Simply put, the Cenotes are a truly remarkable wonder of the earth.

At one time, these caves were the main water source for the Mayan people, but now they are primarily tourism attractions and reminders of an ancient time. People visit them to snorkel, cliff jump, or if they’re ambitious, put on scuba gear and descend into their dark underwater tunnels.

It was my first time and I had no idea if I was ready for any of this. I flew into Cancun the day before, Christmas Day to be exact. I suppose this dive and some of the other things I did were my Christmas present to myself. I left early for the marina the next day, not wasting any time. When I got there and checked in, the divemaster Eduardo greeted me and asked me when I had last done an open water dive.

“Uh, a couple months ago when I got certified, then again in a local pool last week to test my gear.” This is all great if I’m diving shallow reefs, but the caves??? I looked for doubt in his face, and didn’t see it. A hundred different things could go wrong in a cave dive, and I was nervous as hell. Could I really do this?

“Are you claustrophobic?” he asked. I told him no, but wasn’t entirely sure how true this was. I went spelunking once when I was 16, and don’t remember freaking out.

“Okay, wait here. I’ll be back in a few minutes and then we’ll go.” Well I guess that settles it. I’m diving the Cenotes. And if I lose my shit in the middle of a dark tunnel and it’s game over, at least I went down doing something awesome. No, Dan Hagen, DO NOT talk like that. Don’t even think it.. you’ll be fine in the caverns, it’s what you came here to do and you know it’s going to kick ass. YOU’RE going to kick ass. Don’t listen to the I can’t do it voice in my head, just like it says in The Power of Now. You got it.. and at the worst if you can’t dive then you can always snorkel… But then if I do decide to dive it and something goes wrong in a tight spot, what am I supposed to- NO, DAMMIT, stay cool and quit freaking out!!!

This kind of inner monologue went on in my head for an hour. I could not for the life of me keep my cool. But if at any point I felt like it was beyond me, I would shamelessly call off this ambitious dive and snorkel around the pool instead. I got this.

We got to the Tajma Ha Cenote close to Playa Del Carmen an hour later. We unloaded our gear at a concrete table next to the stairs leading down to the cave entrance, and carried our tanks down to the edge of the pool. Already, I felt better. The cave was every bit as beautiful as it looked in the pictures. When illuminated by the sun, the water would glow and cast flickers of light all over the cavern walls and ceilings. It reminded me of the scene in Tron, when Flynn and his program friends discovered the pure energy stream halfway through the movie. That was what this water looked like. Already, I could feel it calming the monkey fight in my head. I sat by the edge of the pool as twenty little minnows swam up and tried to eat my feet, and failed miserably.

Eduardo split us into two groups, and I was placed with an English man and his teenage son and daughter. We got into the water with our gear and I was as ready to go. The cave descended for twenty feet into a large open chamber, and then descended another 20 feet to small tunnel that eventually reached another cenote and daylight. Then it continued towards another small opening, and a stop sign marking the end of that channel of the Riviera Maya. To keep divers from getting lost, the path was defined by a golden line that ran along the cavern floor. We swam in single file, with Eduardo in front, the family behind him, and me at the end, out of the sunlit pool and into darkness. We went through a narrow channel and descended towards the first chamber. I was already having trouble equalizing.

Equalization is when you open the air flow in your ear canal to match the pressure changes in your outer ear, which is done by swallowing or closing your nose and gently blowing pressure into your ears. In diving, if you descend too far without doing this, it can rupture an eardrum. It wasn’t the first time my right ear has been stubborn. Eduardo swam up, grabbed me by the shoulders, brought me up a few feet, and then slowly back down. I felt the relief and squeaking noise of the pressure blowing out of the ear canal. That seemed to get it. Game on.

We descended into a big open room with stalactites along the ceilings and the water surface high above. I think this was the bat chamber he was telling us about. By now, there was only a faint glow of daylight coming from the entrance, which seemed far behind us at this point. We turned around and swam back along a narrow passageway on the far side of the cavern. I wasn’t bothered by the tight passage – as good of a sign as any that I’m not claustrophobic. Soon, we were swimming back towards the dancing beams of sunlight at the entrance.

I got to the surface, relieved and satisfied that I made it through my first cave dive without any major bangups. Eduardo told me that because of my equalizing problems, he could only take me halfway for the second dive. I didn’t want to hold the others back, and decided to stay out. I snorkeled around the pool while the other divers went back in.

It was sick as balls, but not the main reason that I went to Cancun. I really wanted to dive the underwater Musa museum just off of the coast. What I didn’t know was that the coastal weather conditions in the winter season are inconsistent at best. When I went back to the marina a couple days later, they had cancelled that one and all the other reef dives, due to wind and choppy water. No snorkeling either. Too bad, as you can see here, it’s awesome.

But if I can’t dive, then I’ll snorkel. And if I can’t do that, then I’ll rewatch Star Wars: The Force Awakens at the local shopping mall cinema and bookmark the rest of this diving for another season.

This story continues at Arena Mexico.

Calgary to Canmore: A Shitty First Day

So, Canada happened. But Juneau happened before it, and that was only because Burning Man did not. I tried to buy tickets to Burning Man this year after seeing all of the videos and pictures of the festival – its artwork and its people, its burns, its whole freaking aura – only to discover that a whole shitload of other people were thinking the same thing. Its ticketing system amounted to 2 million people all trying to buy 40,000 tickets in the time window the size of a golf ball. I missed my window by microseconds.

That left me an extra week to work with and decide on some other adventure, and hopefully something at least as good. It’s no secret that I’m obsessed with Alaska, so I looked for something there that I could fit in at short notice. I had never been to the southeast panhandle, which is a bit different from most of what I saw the first time further north. I added Juneau to my Canada trip on a whim, which was already booked and ready to go. So it was a week of glaciers, forests, big misty mountains instead of a desert metropolis. Burning Dan will happen another time. Screw you, ticketing system.

Juneau came and went in a blur of rain, ice, whitewater, and fog. But it served its purpose. Before I knew it I was loading my gear into an SUV cab and riding to the Juneau airport on an uncharacteristically sunny morning. I lucked out. There was hardly a drop of rain for both of my big days outside, which says a lot for an area where the locals don’t use umbrellas, but put on rain gear and learn to ignore it.

When I checked in at the airport, the agent spent 45 minutes trying to figure out what to do with my bike box. Clearly they’ve never dealt with a huge pie shaped bike box before. Hassle though it may be, it’s the only one of its kind that doesn’t screw up the brakes or derailleur, and doesn’t require me to remove the pedals, which are rusted onto the crank arms anyway. Plus, it has a wheel kit at the bottom, making it super efficient to wheel around. Honestly, it’s probably about as much as I can do to minimize the logistical pain of bike travel. In this case, I was a few minutes away from missing my flight, thanks to the extra attention from the attendant.

Four hours later, I landed in Calgary. By coincidence, it happened to be Canada Day, which was also the first of 10 days of the Calgary Stampede. Every summer, hordes of people come together in the city for parades, barbecues, and rodeos, and the city transforms into a huge festival of wild horses and the cowboys who chase them.

I didn’t care much about this, but I did want to see the downtown fireworks that evening. I made a few friends at the hostel and a group of us left to watch it along the river. The sky to the west darkened behind the red and white explosions, and I thought ahead to my journey out that way. I was two days out from my bike trip into the big mountain country. The Icefields Parkway of Alberta.

Later that night, I hung out in the hostel back yard with Melanie, a French backpacker who had spent almost 9 months traveling around the US and Canada, and was in between another short roadtrip and a job at a nearby cattle farm. These trips always bring interesting travelers like her across my path, who are just as interested in my adventures as I am in theirs. We had beers and talked for hours, trading stories of our time on the road.

Later that night, I hung out in the hostel back yard with Melanie, a French backpacker who had spent almost 9 months traveling around the US and Canada, and was in between another short roadtrip and a job at a nearby cattle farm. These trips always bring interesting travelers like her across my path, who are just as interested in my adventures as I am in theirs. We had beers and talked for hours, trading stories of our time on the road.

I spent the next day working out logistics that needed to get done before my bike trip. It took most of the day. I hauled the pie box out of the storage shed, reassembled the bike, took it to the shop to fix the wheel truing, packed my computer and extra gear into the box, and FedExed it to Vancouver. I had one week to get to it there, and as long as I did, my adventure would continue along the coast.

After everything was squared away, I was exhausted and needed a drink. Melanie agreed, and we walked into downtown to find some good bar food and whiskey to take the edge off. We sat down at an 8th Ave tavern, which for the Stampede seemed unusually quiet. When I asked the server about it, she said that the second day is the “calm before the storm” and then the next day is when it really begins to go nuts. She went on to say that people in corporate jobs will take off for the week and return to their old food services jobs during Calgary Stampede because they can make thousands of dollars. I could feel the energy simmering in the city. This was Calgary’s equivalent of Mardi Gras.

Next morning, I awoke to the rattle of snare drums and bagpipes from outside. A marching band was warming up for the parade, and it happened to be right next to my side of the hostel. As their drill leader hyped them up for the big day, the bagpipes were soothing to the nerves. This was it. I was hours approaching the open road. I would make it to downtown Jasper in four days this all goes according to plan. As Roland Deschain would say, there will be water if God wills it.

Melanie said goodbye, we agreed to stay in touch. Her time in Canada was coming to an end and mine was just getting started. I left with my loaded bike and rode through a city that was packed wall to wall with cowboys, vendors, and a huge parade of horses. There was no more holding back. This stampede was full on, as was a bike tour more than a year in the making. As I’ve already said, I didn’t really care much about this whole scene. I’m not that kind of cowboy. What mattered to me was distance, which I needed to catch up on due to a late start. Unfortunately, the entire square perimeter of downtown was blocked off to traffic and crowded street to street.

I finally found an underpass and went underneath the main arterial street on the south end. As I headed west, the god drums of the marching bands faded behind me and uncertainty lay ahead.

For a while, I followed the Bow River on a city bike path that went out to the beltway. From there, it got confusing. I needed to get onto the TransCan Highway, but there wasn’t bike accessible shoulder at that point. So I had to spend the next fucking hour going around side streets, pointlessly winding bike paths, and a suburban neighborhood before rejoining the highway and the big shoulder I was looking for. If it weren’t for Google Maps, it would have taken me even longer.

The road straightened across the open plain while the sun was poised brutally high in the sky. The price I would pay for sleeping in. I crested and descended rolling hills uneventfully for hours as the spires of Canada’s Rocky Mountains slowly came out of the burning haze and into clarity. There was one last chance gas station at the 22 junction, about halfway between Calgary and the mountains, to refill my already depleted water bottles. It was blazing that day in the ranchlands.

I continued up huge hills against hot headwind as flies landed all over my head and arms, crawling and buzzing in my helmet. At times, I could go downhill just fast enough to blow them off, only to have more land on me when I slowed down again.

I finally got to the edge of the mountains in the late afternoon, out of water and pushing onward to the next gas station to refill. To my benefit, the mountains blocked the sun from anymore of its punishment. I found a small pond next to the road to cool off. In that kind of weather, it’s the only bearable choice I have. I stopped at the first store I saw at Dead Man’s Flats, five miles from my campsite. I was almost there. Fucking hell, it’s been a day.

As I sat outside mowing down a gas station sandwich and Gatorade, I heard a pop and hissing sound come from my right. That’s a strange noise, I thought. Could somebody be using the pressure pump around the corner? It went on steadily until I noticed the rear tire of my bike deflate and the hissing stop. It just blew out of nowhere. Not from riding over glass or nails, or doing anything stupid. No, it just decided to blow out on its own. What the fuck???

Furiously, I took the tire off to figure out what happened. I found a big hole in the tube where it beaded into the one of the spoke holes and eventually blew. It was the result of an improper installation on my part and probably an under-inflated tube. So it was my fault, even though that didn’t make me feel any less angry.

I called the shop in Calgary that fixed the truing yesterday for advice (not their fault, I didn’t ask them to check the tires). The guy told me to install a new tube and work it under the bead all around, and reinforce the rim with electric tape, and it should hold. I nervously hung up and took his advice. Would this happen again further into the tour? Like say, when I’m flying down a mountainside? If so, would I crash my bike at worst and wind up stranded at best? And if I do get stranded, what then? These challenges all feel very real at game time.

Some local electrical contractors noticed me and offered a ride in their utility truck as far as Canmore. YES! That’s where I’m going! I loaded my gear into the back and rode in the back seat for the last 5 miles straight to my campground. It was encouraging to know that good people were around to help a traveler out, and that if things really did go south, that I wouldn’t be left entirely to my own agency.

All of the bullshit aside, I made it there at the planned hour.

I set up camp, fixed my bike, and walked into town to get supplies. The sky to the northwest blazed in orange and gold above the silhouette of Cascade Mountain, twenty miles ahead. It was a fair reward for all the trouble I went through that day.

I went to sleep in my tent that night, uncertain if my bike would hold out for the rest of the tour, and if I could really do this. There will be water if God wills it.

Timelapsing the California Coast

I had my first chance recently to try out one of my newest hobbies as of late: Timelapse Photography.

I chose California’s Highway 1 for this because it is famous for its beautiful oceanside bluffs and winding turns, which go for hundreds of miles along the shoreline. My idea was to rent a car for the weekend and spend two days filming the highway with my camera mounted on the windshield, starting and ending at the LA and San Fran airports.

It would take two days. Normally I wouldn’t mind camping or sleeping in my car, but I needed somewhere to set up my computer at the end of the first day to load up my footage and adjust my settings. Clearly, none of the hotels on that highway were hurting for customers. I spent a whole evening trying to find an affordable reservation, but almost every mediocre hotel in the area was at least $200. And some of them even wanted a two night minimum, fuck you. I finally settled with a Motel 6 in Morro Bay, about halfway up the drive.

I made it work after some trial and error. I set my camera to manual mode, and shut off the auto focus and image preview, eliminating extra processing and allowing the camera more time to save each shot. It was done with the following equipment and settings:

Gear

- Canon EOS Rebel SL1

- Canon EF-S 10-18mm f/4.5-5.6 Wide Angle Lens

- Platinum 67mm ND Filter

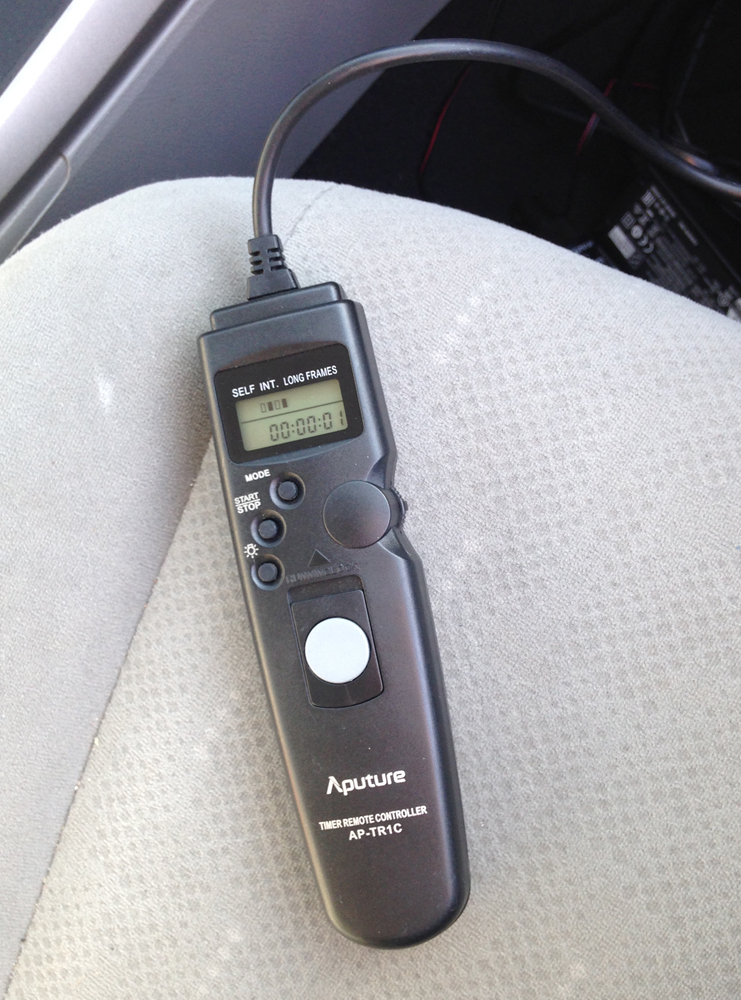

- Aputure Timer Remote Control

- PanaVise Suction Cup Mount

- CyberPower RoadTrip 175 Power Inverter

- Canon ACK-E8 AC Adapter

- Transcend 128GB SDXC Memory Card

Settings

- 14mm focal length

- f/25, 1/4sec, ISO100

- 1 shot per second

- Playback at 30fps

Neutral Density Filter

One of my biggest complaints about most of the drivelapse videos I’ve seen is that they’re done with fast shutter speeds, causing the picture to look jerky and unnatural. In this video, I needed to create motion blur by slowing the shutter to 1/4sec, rendering a smoother, more natural looking picture.

The problem was that I also needed a low ISO and wide aperture to focus on the landscape view properly, but couldn’t slow down the shutter without overexposing. This was solved using a Neutral Density Filter, which I first heard about from this guy. It blocks light going into the lens without losing any color or picture quality, so you can film at slower shutter speeds and bring more fluid motion to the picture.

Window Mount

There are a lot of DSLR mounts you can use for something like this. I went with this one from PanaVise because it’s small and portable. There was a slight rattle to it, which I had to correct in post-production later. It helped to apply tie down straps, as you see in the picture. That aside, it was sturdy and held in position for the duration of the ride. Depending on the angle of the windshield and size of your camera, you may also need to buy a mount extension with this model.

Aputure Intervalometer

With this device, you can set your camera’s shutter to activate at pretty much any time interval you want. Your camera can shoot on custom time intervals, or on command by hitting the remote shutter button. It is also useful for lowlight photography, when you don’t want to activate your camera directly and risk blurring the picture.

Power Supply

On its own, your camera might get an hour of battery life if you’re lucky. But for something like this, I needed a steady power source that could allow me to drive and shoot for hours. With the power inverter and AC adapter setup, this became one less thing to worry about.

Post-Production

Later, I loaded the footage as an image sequence into Adobe Premiere. I used Adobe After Effects for the level correction and image stabilization. A lot of image stabilizing tools have a way of warping the picture and making it even worse, but fortunately the one in After Effects lets you tweak the settings until you find good middle ground. In my case, I only needed to get a slight vibration out of the picture.

Once everything was ready, I just hit the start button on the intervalometer and started driving. I went for hours around the hairpin turns of the highway to the hypnotic clicking of my camera’s shutter.

The only consideration I have with this setup is that shooting at 1 shot per second was a bit spread out for some of the winding parts of the road. In playback, a lot of it was way too dizzying at 30fps, and so I had to use the straightest parts of the road for the video. Next time I want to try shooting at twice the frame rate, and slightly bring up the motion blur. That, and put a black blanket on the dashboard and use a lens hood to block out the glare.

With a similar setup, you should be able to get good footage to use in your videos. Have fun shooting, traveler.

Packrafting the Mendenhall River

Packrafting the Mendenhall River

I think I’ve found the partiest day trip: The Mendenhall River in Juneau, Alaska. It is an ideal combination of scenic flatwater paddling in view of majestic mountains, icebergs, and glaciers – with the adrenaline of hard-hitting Class III rapids downstream as the river makes its way to sea.

The lake and river are both in the Mendenhall Valley, which comprises of most of Juneau’s residents. By chance, I was able to catch a tourist shuttle from downtown to the park headquarters along the lake. A short walk from there brought me to the boat launch close to Nugget Falls, a big cascading waterfall that pours down the side of Thunder Mountain and onto the lake.

I blew up the raft, suited up, and paddled towards the waterfall, whose meltwater crashed and roared its way onto the lake’s surface. Up ahead, the blue ice of the Mendenhall Glacier rose above the horizon line, nestled between the hardened slopes of rock. Further above, higher, bigger mountains rose above the arm of the glacier. And somewhere above them, the open plain of the Juneau Icefield reached across for some 50 miles – one of many that exist throughout the Pacific Coastal Range, feeding rivers like the Mendenhall.

As I made my way north, the glacier slowly grew in size until it was a massive blue wall of three stories that spanned shore to shore for 2,000 feet. All was quiet, but my head was racing. This place was fucking awesome.

Should I get any closer? I debated it, but I didn’t know very much about this glacier, or how stable the ice was at the edge. Sooner or later a calving was going to happen. And I wouldn’t want to be close to a house-sized block of ice if it fell off. So I stayed far enough away that it would have been a huge wake at the very worst.

I turned south and spent an hour paddling to the other side past icebergs, all while a more distinguished vista of the glacier and mountains above it became apparent. Before I even realized it, I was getting pulled into the mouth of the river and the onset of some Class I-II rapids, which were fair warmup for the bigger ones downstream.

Earlier that weekend, the glacier had what is called a jökulhlaup – an Icelandic term that describes a sudden break in glacial meltwater from the snowfield higher up. The water then rushes into the glacier’s moulin and eventually reaches the river, causing the levels to spike. It was definitely a few feet above normal, and had already flooded some of the surrounding trails around the lake. This isn’t altogether bad in bigwater like the Mendenhall, which just escalate into fun rollercoaster rapids.

After a few small, riffly sections, I came around a left bend and approached Back Loop Bridge and the start of Pinball Rapid, the big Class III of the day. Other boaters told me there really isn’t any one line through it, and I could pretty much navigate on the spot. So that’s what I did, fighting to keep my boat straight through a barrage of breaking waves. I remember seeing a huge hole to my right as I passed under the bridge and worked my way towards a big wave train on river left. It had more than its share of laterals, one of which almost flipped me.

Further down, the rapids settled as I passed a few surf holes and river bends. The last big rapid pulled me into a wave train on the right. I had to fight to stay clear of the flooded trees along the bank, the only potential hazard I noticed on the run. At the time I didn’t notice, but in the footage I got smacked pretty good by a lateral wave about halfway through.

There’s no better place to truly feel alive than in the middle of wild, crashing water.

To Andrew WK, partying is living. While the term “party” can be used as a noun or verb, it more importantly describes a feeling of ultimate Zen or Being. To me, the middle of a wild river is where I’m feeling my partiest.

I made it through without capsizing, and floated along calm flatwater for a few miles past back yards before taking out at a city trail and walking to the road.

I would recommend the Mendenhall to anybody looking for a fun day trip in the water. If you don’t have your own boat, local outfitters rent kayaks along the lake and offer guided raft trips down the river all summer long. From experience, I would say that either way you do it is very party.

Bikerafting the Shenandoah

It was my third weekend to do something adventurous, and I wanted to get in at least one good packrafting trip on a local Virginia river. In my area there are three: the Shenandoah, the Maury, and the James. Having grown up in the same watershed, as both streams from my family’s farm eventually get there, nowhere felt closer to home than the Shenandoah.

I decided to paddle the section between the towns of Elkton and Shenandoah, since both had accessible launch points. At first, I thought I could lock my bike somewhere near the takeout at Shenandoah, drive back to Elkton, float downriver to it, and then ride back. Then I changed my mind, broke the bike down, and strapped it to the bow of my raft along with my day cargo, and brought it with me on the river.

I had done a lot of trips with the bike or the raft, but this was the first time that I combined them. I had seen trip reports of other guys doing this in more remote places, and figured it was time to test the whole bikerafting idea myself. I pushed my bike-heavy raft out into calm water and paddled by a herd of cattle from a nearby farm. It was a bit awkward at first, as everything wasn’t entirely secure, but I managed. I didn’t have a full paddle range and needed to push the bike out further to paddle comfortably. That aside, it was fairly easy to get around in the water. And Alpacka rafts are more than capable of supporting that kind of gear.

As for the river, it was about what I expected. Most of the rivers in the valley are pretty tame, with Class I-II rapids spread out between big stretches of flatwater. The Shenandoah and the James don’t really pick up until they cut through the Blue Ridge Mountains, giving way to bigger Class III rapids and rock gardens. At the end of the summer, the levels were low, and navigating the rapids really had more to do with finding the deepest channels so I wouldn’t scrape over the riverbed. I had to get out a couple times to drag my boat over shallow areas. I went fairly swiftly on a gradient for the first five miles, which was great. The end stretch had a long, boring pool of two miles to the dam at Shenandoah.

I made it to the exit ramp after a couple hours, reassembled my bike, packed up my raft, and rode back to Elkton. Cause after all, I am nothing if not portable.

Packrafts can bring more options to your cycling expedition. Like me, you don’t have to let water stop you. They are rugged enough to get you and your bike across rivers, lakes, and even fjords. And they open up even more options, if like me, you like to run big rivers. You can ride out somewhere remote, stash your bike, and paddle down a whitewater run without the hassle of coordinating shuttles.

The biggest consideration I learned right away was that paddling with my bike and cargo greatly reduces its maneuverability. It is more than capable as a standalone boat in technical swiftwater, but I don’t recommend paddling with your bike and gear on anything higher than Class II rapids.

That, and touring with one will take some trial and error. My packraft and river gear add about ten pounds to my bike cargo, which I hate carrying on my back for very long. The top of the front or back pannier racks would be ideal for storage. Definitely be as ultralight as you can with the rest of your stuff, and keep in mind that a trailer won’t work unless you’re willing to go back and forth over a river, and that’s probably overkill. It may be worth it to ship the raft somewhere ahead of you, as I’ve done before.

Further information on the technique of bikerafting can be found here.

On my way back home, I pulled off the road for some good diner food at Thunderbird Cafe, solely because of the name. It didn’t disappoint.

Gauley Season

My last weekend in Appalachia was an all out balls to the walls whitewater shitstorm. I rafted West Virginia’s world famous Gauley River, a wild run of Class V rapids back to back, and got everything you could want out of a whitewater rafting trip. Huge wave trains, big ledges, powerful crashing torrents. The Gauley has it all.

Dropping 668ft at an average of 28ft per mile, it runs on a high gradient for 28 miles between the Summersville Dam and its confluence with the New River downstream. In the summer, levels and difficulty can vary, but all of that changes in the fall. Starting every weekend after Labor Day, the Army Corps of Engineers releases the Summersville Dam at a controlled flow of 2,400cfs for six consecutive weekends. The result is a huge series of torrents that cascade voilently through more than 100 rapids between the dam and the confluence below, drawing rafters and kayakers from all over the world.

I discovered it when I was planning my return to the New River Gorge. Commercial outfitters in the area shuttle rafters to both the New and Gauley Rivers, and though the New River is the bigger and more scenic of the two, the Gauley exceeds it sheer technical bone-crushing power. If it were a metal album, it would be the Heartwork-era Carcass of rivers.

There are five Class V rapids on the Upper Gauley, and they have plenty of III-IV rapids between them. Boulders and undercuts can often be seen along the riverbanks, necessitating scouting if you don’t have a guide with you. Its rapids – though iconic and well-known – are not for beginners or for the careless. I knew that guided commercial rafting was the only remotely safe way I could get through them, seeing as my kayak roll still pretty much sucks and I sure as hell wouldn’t try it in my packraft.

I drove out to Ace Raft on the first Friday evening of the season, slept in my parents’ van, and went down early on Saturday morning to the main building to check in. They had us sign release waivers, taught us basic whitewater safety, got us our paddling gear, and boarded us into a Gauley-bound school bus. We reached the put-in at Summersville Dam an hour later, where they organized us into different rafts. I was placed in a group with three other guys and a guide named Bear, a large bearded fellow and experienced riverman. I walked over and greeted him.

“So you just came out here by yourself?” he said.

“Yeah, it’s just me,” I responded.

“That’s wierd. Don’t you have friends you could bring with you?”

“Yeah I do, but they all pussied out!”

We got in the river, which at the onset was pretty cold (wise of me to rent a wetsuit at the lodge), and hit some good III-IV rapids early on as the fear and energy escalated. There were about thirty minutes worth of choppy waves and small holes to contend with as a warmup to Insignificant Rapid, the first Class V of the day. We needed all the time we could get to learn or perhaps relearn the paddling maneuvers needed to navigate this stuff. Fog lay heavily on the river and the roar ahead reminded us increasingly that the flatwater just above Insignificant was deceptively calm.

Soon enough, we were pounding through it. It is more or less a huge wave train with a lot of lateral waves and ledges that go all the way down to the pool below. At the onset, its waves are small and manageable, but become increasingly bigger before passing a huge slanted boulder on the right and pouring into a big hole at the bottom. We rolled right through it and cheered in the flatwater.

It was big, but Pillow Rock was bigger. After thirty minutes or so of negligible, smaller rapids, we floated around a bend to the left and into earshot of what was easily the most dramatic and terrifying rapid of the day. In this section, the river channels into a huge crashing torrent that piles into Pillow Rock, a giant house sized boulder on river left. I knew all about it and remembered it well from my nightmares. My arms and legs were ice cold from adrenaline. Holy fucking shit. This is it!

Sunlight glimmered through the morning fog, and Bear steered us right through the middle of the golden, crashing water. We went right for it as turbulent water tumbled all around us, and Bear shouted “Touch the rock!” We smacked it with our paddles before dropping down another hole and washing out of the rapid. We cheered like we were the kings of the river and high fived our paddles.

Just downstream from Pillow, Hungry Mother Hole was ready to chew us up and spit us out of her huge, foaming jaws. Bear had us ferry in from the left and try to surf the hole. It didn’t work out. The left side of the raft got caught under the current, sending all of us except Bear into the water. In the camera boater’s footage, I can be seen tumbling out and flipping over as my body hit the side of the raft. I came up underneath for a second and kicked my way back to the side. Bear helped two guys back in while I scrambled back into the raft and helped the last guy in from the right.

We continued onto Lost Paddle, the longest Class V section of the river. It has four drops and is loaded with undercut rocks on both sides for most of the way. But nothing that can’t be avoided, as it mostly channels on a center line. We hit the first three drops without any trouble, including the 9ft drop at Hawaii 5-0 Wave, before eddying out to river right and catching our breath. We had one more drop, Tumblehome, the last and most nervewracking section of the rapid. True to its name, it threw us out of our seats, though we all stayed in the boat. Bear yelled at us to keep paddling as we tried to scramble back into position.

Iron Ring was next, a short and sweet little powerhouse of a Class V. It has two 8ft drops, which at dam season levels amount to a huge, beautiful wave train. We hit it head on.

There was one more Class V rapid left. The horizon line slowly vanished ahead as we approached the roar of Sweet’s Falls, the last of the “Big Five” of the Upper Gauley. It is a 14ft waterfall with a small flume right in the middle, giving boaters a smooth line through if they get it just right. A few feet too far right or left will surely mean a dramatic wipeout. Bear steered us smoothly in from the right and we got it by the throat. We hit a small hydraulic at the bottom and back-ferried past the boulders on river left.

Up ahead, we saw an injured kayaker in the water. The camera boater from one of the other outfitters had dislocated his shoulder going over the falls. We paddled up to him, Bear carefully got him into the raft, and we ferried him to shore. Somebody downstream recovered his kayak and he was safely evacuated. All was well again on the river, but it reminded me that you can never be too careful out there. Not even when you know what you’re doing. Bear tied down our raft and we went up to the tents along the banks for a grilled lunch.

Rafting outfitters stop all along the shores of Sweet’s Falls to eat lunch and watch the boaters go over the waterfall. We ate burgers and traded stories with the other groups about where we fell out, which at this point almost everybody had done somewhere.

I came back from the outhouse and saw a raft go over the falls and flip at the bottom, making for some disastrously awesome river carnage. The left side of the raft turned upward from a hydraulic, sending one guy sailing a few feet into the air. The other paddlers tumbled to the right, and half of this newly jettisoned dude landed on the capsizing raft before he tumbled into raging water. Everybody else fell out the other side. People on both riverbanks cheered like they just saw their favorite UFC fighter kick somebody into another timezone. The first thought that came to my mind was HOLY FUCK!!!!! They washed out into calming flatwater and recovered downstream.

After lunch, we got back in and paddled another few miles to the takeout at Wood’s Ferry. Most of the rapids were tamer and more spread out, giving me time to relax and ponder what it all fucking means. By the end of the day, I was certain that my balls had increased in size by at least twenty percent.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Upper Gauley River is the whitewater trip of a lifetime. But as is the case with any big river, you have to know what you’re doing. If you go, I recommend that you do at least one trip on another IV-V as practice, like the Lower New or Lower Gauley rivers. Both of those runs are tamer and more forgiving to swimmers. You should definitely know all of the commonly used paddling maneuvers and absolutely know what to do when you fall out. All that said, it is so worth it.

Bring your game face to this badass river, and take on the finest rapids in Appalachia.