In Memory of Iohan

In Memory of Iohan

“I Iohan want to see the world. Follow a map to its edges, and keep going. Forgo the plans, trust my instincts. Let curiosity be my guide. I want to change hemispheres. Sleep with unfamiliar stars. And let the journey unfold before me.”

Iohan Gueorguiev was an adventurer. He captivated the minds of countless people as he traveled by bicycle and packraft across the Americas, documenting his amazing adventures on his YouTube channel in a video series titled See The World. Beginning in the ice roads of northern Canada in 2014, he spent months traversing the Yukon and Alaskan highways before making his way through the American national parks and continuing south through Mexico. After volcano hopping in the Central American jungles and taking a paddling detour around the Darien Gap, he finally reached the shores of Colombia, all while filming and uploading his footage for us to enjoy. Years and countless stories later, he reached the high mountains of Patagonia at Lake O’Higgins before returning to Canada to work and wait through the pandemic.

And that was where his epic Pan-American adventure came to an abrupt and tragic end. The cycling community received a note from one of his touring friends in Argentina that he passed away about a month ago. That he suffered from chronic sleep apnea and insomnia, to the degree that he took his own life to end the pain. So many of us had come to love his videos over the years, and were shocked and saddened that this would happen to such a brilliant soul. I’m still trying to process my own feelings as I write these words.

I followed Iohan for years. He was one of the first people to truly inspire me to go on my own adventures and capture the experiences in video and written word. He had a purity to him that I always admired. His sense of adventure was simple, and genuine. Whether making friends with stray dogs, staying with host families in remote villages, or shooting an epic panorama, he was always able to capture the moment and tell a story that connects and resonates with us.

And so as I go through his old videos, so many things come back to memory. Like the Athabascan woman who sang about Denali in her native tongue. Or when he crossed paths with Sarah Outen on the Alcan Highway. And then camped on a volcano high above Guadalajara. And the time he tried to ride the back roads in Panama, only to see them turn into a mudslide and force him to hitch a ride out in somebody’s truck. And of course there were the incredible panoramas of the remote Bolivian highlands. To the soundtrack of Spanish folk music, Iohan was riding on the bottom of the screen, trying to fit the huge landscapes of the Andes into the picture.

And he was always meeting kind folks and animals along the road. He was a friend among many horses, dogs, cats, alpacas, and townsfolk. And yet, always moving on. Because he wanted to see the world. He wanted to follow the map to its edges and keep going. He wanted to let the journey unfold before him. And then he wanted to share it with us.

It’s impossible to say how many of us have been impacted and inspired by his journey – one so suddenly brought to an end. It never seems fair to see life taken away from someone who lived it to its fullest. But this is a story that will live on. As I speak, a group of his friends are planning a memorial in Ushuaia. I want to see it one day and thank him for sharing his life adventure.

He is Iohan, the Bike Wanderer. And while he may no longer be with us, our hearts are with him in the wilds of Patagonia.

The Route 66 Bike Tour

The Route 66 Bike Tour

Recently my Facebook feed brought up a photo album from ten years ago of a bike tour I did from Joliet to St. Louis on America’s historic Route 66. It was the first major trip I had taken since I moved to Chicago almost two years prior. Up to that point I was content exploring Chicago’s neighborhoods and finding things to do in the city. And as fun as it was, it did eventually feel like a normal part of my life. By the early summer of the second year, I was starting to look beyond the city limits for new things to explore. This bike tour in particular was the first multi-day outdoor trip I had ever done, and happened at a time when I was just beginning to find my place in a bigger world. Starting on a dark highway just southwest of the metropolis I had spent two years getting to know, I faced an uncertain future.

The Metra train left the city and made its final stop at the southwest suburb of Joliet in mid-evening on a Tuesday. I wheeled my bike into the platform elevator next to a young guy in a wheelchair. He asked me about my trip and I told him I would get to St. Louis if all goes well. He went on to say that he cycled a century not long ago on a handbike. Then he wished me luck and wheeled in the opposite direction as I turned south, already feeling inspired and challenged.

I rode southward out of Joliet on the main corridor, eventually leaving the last stoplight behind and continuing on into a dark, silent prairie, with no idea how far I would get or where I would stay. There was little to see between the towns other than farmhouses silhouetted on the dark horizon, and occasionally the headlights of a passing car. I soon reached Wilmington and was greeted by the Gemini Giant, the first of many classic landmarks on the route.

Four miles after that was Braidwood, another quiet town in the late summer night. Lights outside of a diner remained open, illuminating icons of an older era.

The interstate was just west of the town, where I turned off from the main road to find a shitty hotel for the night. I found one near the exit, checked in, wheeled my bike into the room, and turned on the TV. A huge rainstorm was closing in, according to the forecast. I went back outside to the far end of the parking lot and looked out at the west across the interstate towards the approaching storm. It was all for the best that I didn’t try to ride any further.

I continued south from Braidwood the next morning. For hours I rode on a straight, flat highway, passing an occasional gas station or diner with Rt. 66 memorabilia. A Polish friend of mine went on a roadtrip in this same place a year later, from Chicago all the way to Santa Monica, and posted all kinds of pictures of landmarks along the way. I told her that if she really wanted to experience my country, that a roadtrip on Route 66 is as American as it gets.

The midday sun was hot as I reached the outskirts of Bloomington, tired from the 70 miles I spent chasing vanishing points on a mostly featureless countryside. When I checked for evidence of chafing, I realized why distance cycling in khaki shorts was a bad idea. I wasn’t in any serious trouble yet, but a rash was starting to form from all of the sweat and friction. It got bad enough that I had to pedal the last 5 miles into the city standing up. I knew there was no way I could go another 200 miles with a ravaged taint, and found a bike shop in town to hopefully get help. The guys there had a good laugh, and sold me a pair of padded bike shorts and bottle of Chamois Butter (or what I like to call Ass Lube).

On a better note, my Couchsurfing host in Bloomington had the most kickass array of old Nintendo gear I’ve ever seen.

I left town the next morning, wondering if I would make any more rookie mistakes, like say, taking the wrong road out of the city. After what ended up being a ten mile detour, I found the main road again and continued southwest. It was more of the same, with long stretches of flat, open road, and a town with a stoplight or two every 30 minutes. I reached Springfield halfway through the day and took the main beltway around it. I continued south on a steady pace, losing track of the little towns and their names as I rode on for hours into the afternoon. I must have gone at least 80 miles so far, yet for some reason I had an endurance that I couldn’t explain. I wasn’t getting tired. I just kept going.

I made it to Carlinville around 6pm and found a good Sicilian pizzeria at the town centre. The hot sun was finally starting to disappear behind the buildings. Maybe it was the nice temperature that put me in such a good mood. Or the boost of protein that gave me such a strong second wind. Or maybe it was the realization that even with my mistakes, this multi-day adventure was coming together without any major problems. Whatever it was, I was going harder than ever on the country road amidst the darkening cornfields, even as the day was coming to an end.

I could have kept going, but I decided to stop in the town of Staunton 20 miles later. St. Louis wasn’t much farther, but I didn’t want to get there at night. I found a hotel on the west edge of town and checked in. From Bloomington to Staunton, I rode 130 miles that day.

A bike path crosses the main road going south out of town. When I reached it the next morning, I decided I had seen enough of Americana and took it into downtown St. Louis.

Route 66 continued west through the city. I rode on for a final hour before reaching the west suburbs where I planned to stay with a Couchsurfing host for the weekend.

I started using Couchsurfing in 2008 when I moved to Chicago and needed a place to stay while I looked for a job. After settling into a routine, I started hosting people, and actively attended weekly bar meetups with the local Chicago group. Over the years, Couchsurfing became my primary way of meeting people when I traveled to new cities. It turned out that my host for the weekend, Tiffany, was also active in the community, and an organizer for the St. Louis Couchcrash that weekend.

A Couchcrash is like a marathon of events that each city does once a year, usually in the summer. From three days up to a week, local organizers schedule bar meetups, walking tours, picnics, house parties, and whatever else they can do to showcase their local scene to the visitors. Many Couchsurfers from out of town come together for the Couchcrashes and tour the cities in big groups, all people of whom share the same ethos of community and travel experiences. You can find events like this in New York, DC, Chicago, Minneapolis, and many other cities (or at least you could before the Covid-19 pandemic banished all of us to Zoom meetings).

That night, Tiffany drove me to their Friday night event at the City Museum, a huge monstrosity of what I could only describe as a jungle gym for grownups. Inside the big downtown building is a network of tunnels, mega-slides, and caves that span over multiple floors. You can find a massive ball pit outside, if you can handle the pain of children throwing watermelon sized balls at your face. And there are even more slides, a ferris wheel, and bus hanging off of the roof. And to top it all off, they have a bar on the bottom floor. A group of us hung around drinking there before exploring the cavern passageways and eventually going to the rooftop to view the city.

We went to a picnic and city zoo the next day, and then met up for a big bar crawl in downtown that night. It was a fun weekend overall, and wouldn’t be the last time I would crash in St. Louis in such a fashion. Throughout this event and others, I became familiar with the network of Couchsurfers who built an online community of travelers in cities across America and elsewhere.

I left Tiffany’s house the next morning and rode to the train station in downtown. I wheeled my bike on the train car for a 5 hour ride back home. I didn’t realize until later that the tire pump in my cargo had the wrong valve… good thing I didn’t get any flats on that trip!

Since then, I continued to take other trips all across Illinois, like the weekend later that year up the Great River Trail on the Mississippi north of the Quad Cities. Or the overnight century in a state park south of Carbondale. Eventually I toured even bigger places out west with a newer bike and better gear. Over time, bicycle touring became just one column among five different things I liked to do. I started to feel like the open road was just one way to go on an adventure. But even more could be explored in the oceans, down the rivers, in the high mountains, and from the sky. Even now, the next adventure is in the forefront of my mind. It never stops.

Return to the C&O Towpath

Return to the C&O Towpath

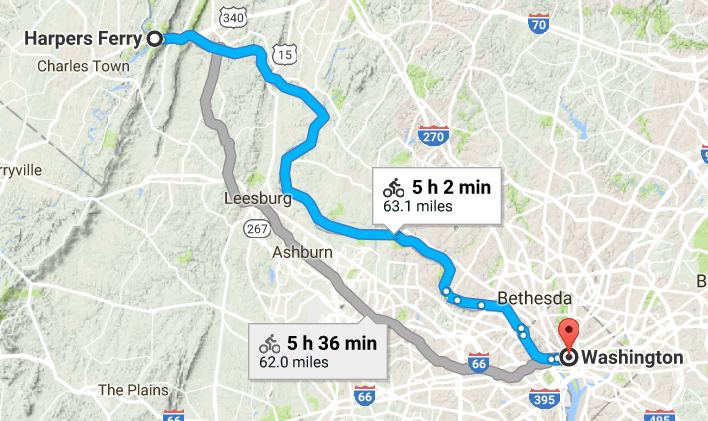

It was 5:30am on Labor Day weekend in Harpers Ferry. The path was wet from rain from the previous day. The air was warm and damp, almost to the touch. It had been almost a year since I last attempted this trail, and was cut short by an Achilles problem in both of my feet. I had intended to get to DC from Pittsburgh on the GAP and C&O trails, but after five days I had to stop at Harpers Ferry and take the train back home. Now, a year later, I was back to the finish the ride. At 30 minutes from daybreak I couldn’t see a damn thing. I got on the path, turned my lights on, and slowly rode east.

Soon, it was light enough to turn off my lights and pick up my speed. I went for 20 uneventful miles along the canal with few other people out. I rode, mostly alone, along the bends of the lovely, meandering Potomac. On a quiet morning like this one the river was like a sheet of glass, mirroring the breaking clouds of the day.

I started getting tired and out of breath about halfway through the ride, taking more breaks than I normally would. I was out of shape for this trip – which might have been part of what caused me so much trouble last time – but felt like I could handle one day of riding. At 45 miles I was getting into the zone and thought I was making decent time. Then out of nowhere I blew out the rear tire. I had a spare tube in my cargo and spent 20 minutes switching it out. I got back on and rode again. It blew out again. What the fuck?

I flipped the bike over and took the tube out to investigate. The culprit was a tiny wedge shaped pebble that punctured the tire and the tubes along with it. I checked my cargo to get out another tube. Shit, I forgot to bring more. So I was forced to patch the one I had. The problem was that the wheel caused even more pinch holes when it went out. And I had to find and fix those, repeatedly inflating and immersing the tube in the canal water, finding more and more holes that I had missed before. Bubbles came out from under one patch and then another pinhole appeared next to it. What the hell is all this? This tube was shot. I had no choice but to try to fix the other one.

Meanwhile, other cyclists kept going by and offering to help. That was reassuring. But I should know how to do this. I used to patch up my mountain bike all the time as a kid. I found a pinhole, sealed it, waited, and put the tube back in the water. Another leak was next to it. This was really getting aggravating. This was the last tube I had. Would I have to call in a taxi just to get out of here?

I patched the second pinhole, inflated, gently checked the tube in the water. Nothing. I think that’s it. I checked the tire and rim again for sharp objects, put the tube on, blew it up to 70lbs, and did a test ride next to my gear. No blowout. Okay. I loaded my cargo and started on the path. I stopped after a minute and checked again. Still holding up. I think that got it. So I rode on. That ordeal lasted two hours.

I think that the C&O was determined to stop me and failed. It did manage to piss me off, twice, but didn’t keep me from my goal. To celebrate, I went out to see the Great Falls of the Potomac, about three miles from where the blowout happened. What was once a silent, meandering river ten miles ago was now a magnificent series of waterfalls tumbling over multiple canyons.

This was awesome, but the trail was very crowded. I dodged cyclists, families, strollers, and dogs, and continued east past the crowds of people. The canal to the left widened under a large cliff and the calming river cut through Mather Gorge, an impressive canyon just after the falls. There was virtually no topography on this trail whatsoever, save the drops along the canal locks. As I neared the 495 beltway, there were 7 locks, so it finally felt like I had some decent downhill. I was nearing the city at last.

The Capital Crescent Trail parallels the C&O a few miles outside of DC and it is paved. I was done riding on gravel and took that the rest of the way into Georgetown. It was a nice day without any wind, so lots of people were on the river in kayaks and paddleboards. I saw a dude in what looked like a red Alpacka, which was good see out here. I’ve been trying to spread the packrafting gospel for years, especially on the east coast. Hell, I even had mine in my cargo, and would have used it yesterday if the weather were better.

Georgetown, the end of the C&O, was busy in the mid-afternoon. And I was exhausted. I needed to find my hostel and clean up. I loaded up a map. It said that less than a mile away was the Exorcist Steps. Wait, what?

That is fucking awesome. Time to go east.

I’ve always hated the street layout in DC. It’s pretty much a clusterfuck of diagonal streets – many of them one way – integrated into a grid system. On a map it looks like a spiderweb. And as an analogy, I would compare it to what we programmers like to call spaghetti code: It’s complicated and difficult to work with. And the bike lanes aren’t much better. I checked my phone repeatedly to find the right streets, and found my way across the city after some aggravating navigation.

That was yesterday. This morning I went sightseeing in DC for the first time in 20 years. It hasn’t changed very much, only now everybody is taking pictures of the monuments with their phones instead of just looking at them. But of course, I wouldn’t do anything like that..

And now I’m in a Starbucks waiting to leave on the train. I’m fielding a hangover from a rooftop meetup last night. After I finished the ride, I cleaned up at the hostel and then mingled around at a meetup in Adams Morgan because I have endurance. I’ll be back again before long, at least to Harpers Ferry. It has become one of my favorite towns in Appalachia.

Dare to Do by Sarah Outen

Dare to Do by Sarah Outen

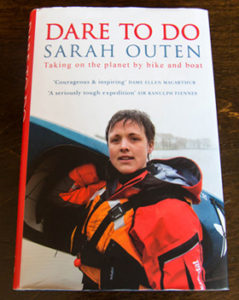

In my spare time, I like to follow other travelers online. When I got into travel blogging, I naturally started to find other people who did the same thing, many of whom were living out truly exceptional stories of adventure. I discovered Sarah Outen in 2015 as she was on the final leg of her 25,000 mile expedition around the Northern Hemisphere. Starting and ending in London, she embarked on a 4.5 year human powered journey around the world by bicycle, rowboat, and sea kayak. She published Dare to Do, a compelling memoir of her global expedition.

Last Christmas, I planned to take a train from Chicago to my family’s farmhouse in Virginia. My parents asked me what I wanted for Christmas, and I told them that I wanted a new tire pump and a copy of Sarah’s book. But I didn’t want to wait until Christmas to read it, and asked my dad to send it to Chicago instead. Unsure if it would get to my apartment in time, I tracked the shipment from the UK to my doorstep down to the minutes. It arrived with hours to spare. Soon, I was riding a Virginia bound Amtrak into the evening. I sat in the train car, reading the first pages of her story as she set forth from the London Tower Bridge amidst the cheers of old friends and new fans.

Last Christmas, I planned to take a train from Chicago to my family’s farmhouse in Virginia. My parents asked me what I wanted for Christmas, and I told them that I wanted a new tire pump and a copy of Sarah’s book. But I didn’t want to wait until Christmas to read it, and asked my dad to send it to Chicago instead. Unsure if it would get to my apartment in time, I tracked the shipment from the UK to my doorstep down to the minutes. It arrived with hours to spare. Soon, I was riding a Virginia bound Amtrak into the evening. I sat in the train car, reading the first pages of her story as she set forth from the London Tower Bridge amidst the cheers of old friends and new fans.

She paddled her kayak across the English Channel with the support of renowned sea kayaker Justine Curgenven, and got to the coast of France where she cycled east on her touring bike, Hercules. I sat in the dining car somewhere in northern Indiana, eating a microwaved pizza and drinking Budweiser. The train rumbled and whistled into the night as Sarah recounted her trek across Europe. The pages flew by. I couldn’t put the book down. As she cycled through Ukraine, western Russia and Kazakhstan, the kindness of people became a prevalent theme in her journey. Many times, she was invited by village families for tea, dinner, vodka, a place to stay, and a fun evening of stories.

In China, she met a young gellow named Gao ya Guang, who was so inspired by her quest that he offered to cycle with her across the country to Beijing. Crazy as it was, they toured the hostile, remote Gobi Desert, forging an unbreakable bond of friendship. Travel does this. It connects you with people in ways that you would never expect to happen.

Somewhere in eastern Asia she was at her wits end with a busted up bike, and I started dozing uncomfortably in and out of sleep in the train car. Trying to sleep in coach all night, usually next to a stranger, is the price to pay for traveling on a budget. I sat up at 3am, too tired to read and too awake to sleep. The dining car finally opened at 7 that morning. I drank more coffee than I needed to and opened Sarah’s book again. Outside, the mountains of West Virginia went by. She just made it to Japan. Here, Sarah embarked on the first of two rowing attempts across the Atlantic, the first of which was cut short a couple hundred miles out by the Tropical Storm Mawar. She recounted the violent storm as its gales relentlessly gave her boat a thrashing. It survived, but was too damaged to safely go on – she called in the coast guard and returned home.

After a year of recovery, training, and outfitting her new boat Happy Socks, Sarah once again left Japan, this time rowing northeast to the Aleutian Islands. She was alone at sea for 148 days, but finally made it to the remote Aleutian village of Adak, Alaska, incidentally becoming the first woman to do so. Here, she reunited with Justine. They island hopped the Aleutian chain for months, kayaking the treacherous, volatile weather systems of the Bering Sea.

She got to mainland Alaska at the end of the summer and cycled across the same highways that I’m familiar with, making the local news as she passed through the Anchorage area. I laughed when she ranted about the Caribou Creek Gorge. I’ve been over that canyon three times, and it’s an absolute bastard to cycle over.

In the Yukon, she met Iohan Georgiev, a nomadic cyclist who I’ve followed online for two years. He had just got out of Alaska on an epic expedition to Argentina and caught up with her on the Alcan Highway at minute 44 of this video. This was the first time I had heard of her story. I was amazed at the scale of her trip, and followed her online ever since. But little did I know at the time the hell that she went through to get there.

They parted ways at the Haines Junction. Iohan went south to the ocean and Sarah continued east. She had to get to the east coast by next spring, and fought her way across the plains of Canada with her fiancée Lucy, in 30 below weather to make it in time.

Back at home it was Christmas Day at the farm. My mom was fixing a turkey dinner and Christmas music echoed throughout the house. I sat in my old room, reading Sarah’s memory of her ride through the states. She got to the Appalachians of Pennsylvania just in time for the spring thaw.

At last, she reached the pier at Cape Cod, reuniting with Happy Socks for the final voyage home. That summer, I followed her story as she tweeted her location and status report each day. The open sea was wildly unpredictable, but to her, she said it is where she truly feels content. I can understand that. To the outdoor traveler, there are places in the world where we honestly feel more connected than anywhere in our normal lives. To me, the mountain country of the great north is where I am truly at peace. And to others, it is the open ocean. Though immeasurable and likely dangerous, we want more than anything to be back out there.

Dare to Do is an inspiring tale of human potential. It is a personable, honest story of human kindness, friendship, courage, heartbreak, and adventure. It is evident in her pages that Sarah’s quest is just as much of a journey inward as it is a traveler’s tale. And until I get the chance to do it myself, I will have to see the world vicariously through her words. I encourage you to do the same. Read her book. Be inspired. Get out there and explore.

The 450 Tour Part 3: The Richardson Highway

Two major highways meet at the junction at Glennallen. It has one gas station, which gets a ton of business in the summer. Most people stop there because there isn’t much else around. There were two bathrooms, and one of them was out of order. So a lot of tourists waited in line to use the other one. I had to use it because I didn’t want to take a dump in the woods earlier that morning (honestly, how often do any of us shit in the woods?), and didn’t know where else to go. Nobody was waiting when I went in, and I tried to go as fast as I could. I came back out to a line of four people. Well, time to get my bike and keep going.

This was the third and final phase of the 450 tour: The Richardson Highway. Here, I would head south along the Copper River Valley for 20 miles, camp out at the Tonsina River, and then take the next day to climb over Thompson Pass. The ride would end in Valdez, where I would stay the night, and then take a Whittier-bound ferry across the Prince William Sound.

I started south. The mid-afternoon sun blazed in the northwest as I rode along the bluffs of the mighty Copper River, looking out when I could at the vast mountains of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. Its peaks range from 12,000 to 18,000 feet, reminding me of the Cascades of the Northwest. Originally, I thought to incorporate a 2-3 day packrafting trip down the Copper River to Cordova, somehow rigging my cycling gear on the raft. When I read that this river has its share of dangerous eddy lines and katabatic wind-driven sandstorms downstream (yes, there is shit like this in Alaska), I decided on the relative safety of the highway instead. But even that wasn’t entirely safe, as I would be flying down a mountain pass tomorrow.

I had one huge hill to clear before a steep descent to the Tonsina River and somewhere quiet to set up my tent. I camped outside of the Russian owned Tonsina River Lodge, fueling up on meat, beer, and caffeine. That night, the 4am sky glowed in what was already a new day in the boreal summer.

I started before the sun came over the mountains. It was supposed to be another hot day on the coast, which doesn’t happen often. I lucked out this summer, as a lot of my outdoor trips ended up having great bluebird weather. Hot as they often were, I would take that over cold rain and fog any day. Though in its own way, I found, the rain and dark clouds can also bring out the richness and magic of the mountain country.

The climb was mostly gradual for 20 miles. The next lodge where I planned to top off my water was closed. I climbed another 5 miles to the next one. Also gone. Fuck, I guess I have to ration what I have over the pass. I didn’t bother bringing my filter, the clogged, worthless piece of deadweight. The road was often steep in places, but manageable. I was surrounded by the huge, steep mountains, with summits carved out by icefalls and glaciers. On any cloudy day, I expected none of this could be seen.

Near the top of Thompson Pass, the Worthington Glacier claws steeply out of a mile high ridge system. I could stop and check it out, or I could worry about refilling my damn water. I had half a bottle left, and was betting on something at the bottom of the other side. There were two more miles to go in the hot alpine sun before reaching the summit. I made it there and looked around the mountaintops, which spread out in a full panorama. Here, the highway descends steeply for 2,600 feet to sea level. I looked at the descending road ahead with a familiar sense of foreboding.

The top of any big bike descent, or river rapid, or scuba dive, always drives me treacherously out of the boredom of my comfort zone and into the thrill of the unknown. I never know what is ahead. And I’m not always confident that I can get through it. But I think my fear is what makes me feel even more connected to the wild outdoors. It could mean hitting a rock at 30mph and crashing on the road. It could mean worse. But despite the risks, I’m drawn to it. This road is horrifying, and horrifying is awesome.

I went flying down the top of the pass for a mile amidst huge green mountains and blue skies. The road went around a loop, and kept going steeply down the mountain. I went fast into the grade and headwind for 10 minutes before I reached the top of Keystone Canyon. Here, the tunnel wind blew through the canyon, forcing me to a crawl. I was out of water, 20 miles from the town, riding along the bends and turns of the canyon. At least the scary part of it was over.

I came around a turn to Bridal Vail Falls, then Horsetail a minute later. The cool moisture got to me. Dammit, I need water! I had left my purifying pills with the rest of my gear in storage, because why would I need them on this tour?

The road turned west towards the town after the canyon, and the headwind was unrelenting. Valdez was 15 miles away. I WANT WATER FOR FUCKS SAKE! Finally, I saw a convenience store across from the airport. I drank a liter of Gatorade and sat outside in the shade, savoring the moment. I am hydrating. Life is good.

No longer feeling weak from thirst, I could enjoy the last few miles of this tour. Numerous ragged sawtooth mountains lined the south end of the valley above the Lowe River and the Valdez Marine Terminal, the big oil port across the bay. Yes, that one. This town was in interesting mix of tourism, local fishermen, and oil industry workers. And on this day, the local DOT was making the most of the hot, dry weather to pave the highway. I saw 5 road crews out, throwing down asphalt as fast as they possibly could.

Finally, I got to the town. I checked in at my hotel and arranged for Nickel to pick me up in Whittier tomorrow. I was exhausted, but not enough not to end this tour with a salmon dinner at the Fat Mermaid by the harbor. A guy with a guitar played Jimmy Buffet covers as I ate and watched the colors of the late day change across the water.

I loaded my bike on the ferry the next morning. It would take six hours to cross the Prince William Sound, but I barely noticed as the boat skirted a million waves along the pristine Alaskan shoreline.

This story continues on the Portage and Placer Rivers.

The 450 Tour Part 2: The Glenn Highway

I got my bike and touring gear out of a U-haul storage in midtown Anchorage and went north through the city. I passed by the neighborhood that reminded me of a woman from 2012, who turned out to be the best ghosting story I’ve ever had. We met online and went bar hopping in downtown on what ended up being a good first date. She was a licensed pilot who worked for a local flightseeing company, and halfway through the night she offered to fly me out to the Knik Glacier as an idea for a second date. So of course I’d be up for that. The night went on from bar to bar, and we continued to have a good time. I followed up later to pursue this whole glacier idea further… yeah, ghosted. Like straight up nothing. After talking up all this game, I did not get my glacier, I got fuck-all. On the bright side though, at least we don’t live in the same town.

But I knew if I was going to get through the next 300 miles, there were more important things to worry about than my dating failures, like the downpour that hit me on the outbound Glenn Highway. I rode into a lot of hard rain and shit for visibility. And my rain gear was about as waterproof as a mesh T-shirt. The big problem was that my rear blinker wasn’t working. Luckily, the highway had a huge shoulder. That said, I don’t know how I survived to tell the tale.

I got to Eagle River after about an hour and waited in a shopping plaza for a bike shop to open. I checked my work email. Dammit, one of the client websites was busted. To fix it, I would have to write about 10 lines of code, but I didn’t think I could do that from my phone without screwing it up even more. I realized that I could patch it with one line in the login process to bypass the bad part of the code for now until I can get back to my hotel next week. I was in the site admin panel trying to wipe droplets off of my phone and code it in. On my phone’s keyboard menu, you have to go to submenus to get to some of the characters used in PHP syntax. A pain in the ass. I saved the file and tested. Looks like that got it. People ask me what I do and I tell them I get mad at a computer for a living.

The bike shop opened and I got a new tail light and set of fenders to keep the wheels from flinging mud on the drive train. It was great service from Alaska Velo Sport in Eagle River, and I’d be glad to recommend them to other cyclists going through. I went north as the rain backed off and clouds started breaking on the ridges.

Thirty miles later, I started climbing the eastward hills into the mountains just after Palmer. What the hell is that sound? Something in my drivetrain was squeaking with each pedal stroke. After some investigation, I realized that the guy at REI forgot to put lube on my chain. I didn’t have any chain lube with me, and the last shop for the next 250 miles was in Palmer, five miles back. After that it’s just me and that road. I called the guy there and asked him if there was any possible way they could wait for me to get back at 6:30. He said dryly, “We leave at 6.” Fuck.

I had 40 minutes to get back, but luckily it was all downhill. And I was hauling ass. I didn’t want to risk a chain break over the next few days in the middle of nowhere. I made it in just under 20 minutes. He lubed the chain for free, which was cool. I finally thought I was ready for this tour. I climbed the hill above Palmer again and listened for the squeaking. It was gone.

Ahead, familiar mountains closed in as I climbed along the rush of the Matanuska River. Clouds lifted, thinned out, lightened, and broke away from mountaintops in the late sun. Soon, I arrived at the Pinnacle Mountain RV Park. It was an eclectic place, full of pretty old junk, flower gardens, ducks, swans, goats, llamas, and alpacas. Antique tractors lined the road in a row, some of them with flags. Flower beds had colors that you would never see in the state, clearly built by somebody with an eye for aesthetic design.

When I walked to the outhouse, I kept getting hissed at by one of the swans. I gave him a wide berth of 20 feet, but it still wasn’t enough not to piss him off. Can’t win em all, I guess. But I wondered, how do they protect all of these pets from wolves and bears?

I waited for the lodge restaurant to open the next day. It was my biggest day of climbing yet, and I needed to eat as much as I could. The lodge owner cooked me breakfast and talked my ear off for an hour. This lodge, its antiques, flower gardens, animals, and quirky random things were her creation. She has it exactly how she likes it. And I like that. She was so much fun to talk to that I lost track of time. I got going at 11:30 for the next pass. But hey, it’s going to be a long day. It’s summer in Alaska.

I’ve done this road before. Right after the RV park is a bridge crossing and the first of three steep uphill climbs over the next twenty miles. I pedaled against an incline, gravity, and doubt. Behind, the familiar stoic King Mountain rose above the roar of the river as it made its way westward. The climb at Long Lake was the next big fight, as I paced for a slow hour on low gears. The Chugach Mountains to the south came in and out of clouds and shimmering glare, occasionally lighting up in breaks of sun, only to be enveloped in showers a minute later.

My favorite part of this pass was near the Matanuska Glacier. Here, the mountain ridges curved along the valley above a bed of forest, split in half by a huge glacial moraine whose streams would eventually feed a charging river. It was good to be back. Not just to be back, but to keep going and make this adventure even bigger and more personal.

Soon, I reached the part of the road that I knew and hated: The Caribou Creek Gorge. The road descends for a mile to the canyon floor, crosses the creek, and then goes back up the other side at an 8% grade for a full mile. It’s a real cracker jack of a climb. But I knew what I was in for, and got going slow on the grade at an easy pace. The important thing is to keep your gears low and cadence high. Head down, pedal, and fight it out. It hurt, but I made it to the top after 20 minutes with no breaks and surprisingly no bitching. The Grand View Cafe was just a mile downhill after the top, and was well earned.

It was a slow weekday at the cafe restaurant, where I chatted with a young Latvian lady working there for the summer. She was jealous of my tour. She said she did the same thing last year from Whitehorse to Vancouver, which is bloody impressive. That’s farther than anything I’ve done. I told her she should get back on the road and she agreed.

I continued east out of the range. Clouds darkened over the mountaintops, dumping sheets of rain on the high tundra. The peaks of the Chugach range broke away from the road as I went eastward. Big grey clouds and summer showers rolled across the plains ahead. I made one last stop at the Eureka Roadhouse for food.

At mid-evening, I was flying down a huge series of hills as the road made its way out of the mountains and into a huge plain of taiga forest and a million lakes. And with them, a horde of mosquitoes. I didn’t care. I was living. I crested a hill and saw the alpenglow of 12,000ft snow capped Wrangell Mountains rising high above the plain, 60 miles away. ATV riders rode along a track parallel with the road. I kept up for a second. I pedaled on, glowing amidst a tremendous, gorgeous landscape.

I was in such a good mood that I thought fuck it, I’ll get to Glennallen tonight. It’s another 40 miles, but I’m kicking so much ass. And it’s been years since I’ve done a proper century, on a tour no less. I charged on, high on endorphins, protein, life.

What you don’t see on a terrain map – the one of this area included – is all of the steep river crossings. Even on a straight road like this, which was mostly downhill. Each creek crossing meant a descent and a climb back up the other side, eroding my energy levels faster than I expected. I crossed a river at 11:00 and spent 10 minutes getting up the next hill, finally getting burned out. I stopped for a break at the top, looked at the trees by the traffic pullout, and thought that’s it. It’s time to call it a night. My hubris got me another 15 miles that day.

I set up camp in the woods next to the road and slept under a lavender sky.

I made for the town in the clear morning. The road straightened out and leveled into a gradual downhill coast as I approached Glennallen. Black spruce trees, muskeg, and brushy tundra carpeted the landscape while patches of fireweed flowers decorated the sides of the road. At midday, I passed the town with the blink of an eye and got to the junction and the end of the Glenn Highway. Here, I would head south to the ocean.

This story continues on the Richardson Highway.

The 450 Tour Part 1: The Seward Highway

Whenever I’m not traveling in the country, I like to be somewhere with a lot going on. That’s why I live in Chicago. When I want to get some good beer and fish tacos, I can find them down the street. When I want to meet new people, I can. When I want to go to a festival or a museum, it’s around. Which was why I based my operations out of Anchorage. Because even though it’s nowhere near as big as Chicago, there was still plenty to do in my downtime. I set up my work station out of shitty hotels next to downtown, which made it very easy to find things to do. For two months, I spent my weekdays in hotels working on my company projects, planning my outdoor trips, drinking, or hanging out with women from OkCupid.

CW was an OkCupid fling-turned-friend from 2012 who I have stayed in touch with over the years. We met up numerous times for pizza or food trucks, where I also met her bestie KM. One night we went to the MST3K Reunion at a nearby cinema. The cast of MST3K and Rifftrax broadcasted the event to theatres all over the country via livestream, and spent two hours destroying some of the best stupid-awesome shorts I’ve ever seen. One of the best ones was a video from the seventies about how kids can have fun with grass. If you want to play with grass, go outside and pull some out, and start braiding it on a table. You can use grass to make a mask! Or braid it into a headband! Or make grass earrings! Fun with grass! I hadn’t laughed that hard since my best friend showed me Maddox’s website.

I also had an email exchange with Nickel, and we met up for a bar crawl date in downtown on my first week. And then it became a fling that lasted for my two months there and after. For many evenings, we met in hole in the wall restaurants or local haunts, or did shots and Game of Thrones at her house. Often times, it was the only chance I had to relax between my workload and outdoor logistical hassles.

So when I got back from a two week adventure in Denali, it was just in time for the annual Pride Parade. And who better to call up than Nickel to join me. Cause I wouldn’t say that I’m out or proud, but I wanted to show up and support Alaskans who are. That, and I thought it would be a good idea for a date.

I went by her house late that morning and we left with her roommate Alpha for the downtown parade. When we got there, a big crowd stood on the sidewalks as numerous floats and groups marched down the street. The local VA, school groups, Alaska Air LGBT, and so on. Later, there was a festival in a nearby park with local folk bands and rainbow bracelets by the truck load.

Nickel and Alpha ran into numerous friends, including DD, who has become a force of reckoning on the local interwebs. She told Alpha about a guy who she recently hooked up with on her Tinders. Which wouldn’t be any big deal, except that her reason for hooking up with him was because they went on a date once a while back, and she remembered that he was a nice guy. Only to figure out later that this guy she hooked up with now was a different fucking dude!

This anecdotal gem and many others can be found on her website All the Dicks. After a bad divorce and some soul searching, she made it her goal to find and score with as many young dudes as she can, because fuck it. Which I think is awesome. You can read all about it here (but note, my dear traveler, that what is read therein cannot be unread).

It was fun, but I needed to catch up on my work, and Nickel wanted to hike Flattop with her uncle. We parted ways and I went back to my hotel.

I was up in Denali for the last 15 days, and at the end of the next week, I would be leaving for another 7. So along with catching up on two weeks of work, my boss piled on everything ahead. This included two big software upgrades, which, if you work in software you would know amounts to a dogpile of QA testing, patching, and retesting. All that afternoon and Sunday went into the first rollout. Then for the rest of the week, I was hurdling smaller jobs to get to the other project before the Friday deadline. Somehow I managed to find time to get my bike from REI and a drink with Nickel at Mad Myrna’s.

That Thursday, I was charging into the night with Red Bull and bloodshot eyes, trying to make my deadline on Friday 9:00 Eastern. In Alaska, that is 5am. At 3, I did what should have been a final QA test, only to figure out that there was a whole section that I forgot to add in from a previous draft. I spent the next hour writing a new block of code, which I hate doing when I’m tired. At 5, I finished one last QA run, uploaded, hit the switch, and fired off a one sentence email to the clients, making my deadline down to the minute.

Then I slept for two hours, worked all day on even more of this shite, tied it all off at 5, packed up my computer in storage, went back to REI for a last minute derailleur fix, and packed up my panniers for the train ride out tomorrow. Fucking hell.

Finally, I was ready to do what this is really about: My 450 mile bike tour from Seward to Valdez. If it went as planned, the train would drop me off in Seward, and I would spend the next week riding on the highways to Valdez, and then board Alaskan Highway ferry for the trip back across the Prince William Sound. It was ambitious, cause it’s got to be when you ride like Dan Hagen.

I got out at the Seward depot at noon on Saturday and went north along the highway, planning to reach the town of Hope at mid-evening. I climbed the mountain passes for hours on a well-paved road and big shoulder, often looking out at the big, forested mountains and blue skies. Halfway through the day, a blanket of stratus clouds spread across the land.

The Summit Lake Lodge marks the high point of the pass, where I stopped to eat. After this, it is downhill for two hours to the ocean, starting with a 6% grade into headwind for a few miles to the Hope Junction. What I didn’t know was that at that speed, an 18 wheeler can fly by on the road and break the headwind, creating a powerful vacuum of tunnel wind that would end up pulling my bike towards the road… WOAH, SHIT!!! I almost got thrown into the road as the truck flew by at 65. I pulled away from the wind, fighting with all my strength to keep control. I screamed in horror for the first time in more than 20 years. Remarkably, I kept it together and coasted back onto the shoulder.

I got down to Hope Junction a few minutes later and continued on Hope Highway, relieved to be away from the traffic and freaking out because I almost died. The silence of that slow two lane road calmed me down. Keep going, Dan Hagen, keep going. You’re 10 miles out from food and sleep. And you didn’t fucking die. Not today.

The highway descends from the mountains to the edge of the inlet and sea level. From there, it follows the south shoreline of the Turnagain Arm for 7 miles west before ending at the remote town of Hope, Alaska. There, I would find hot meat and cold beer.

When I rode few miles out on the hilly coast, I looked and saw a wall of rain engulf the mountains across the water. It was heading this way, and I needed to get to town before the shower did. That didn’t happen. The rain hit my face and arms with a mile to go.

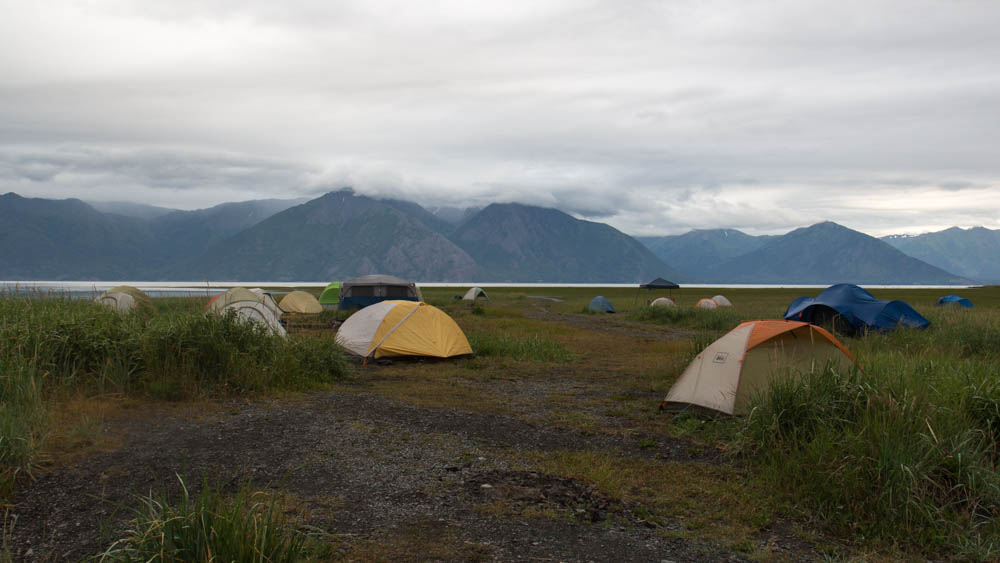

I had spent an entire day alone on this highway. I had adapted to the solitude of the quiet forests and closed in feeling of the mountain country. I felt content riding in the comfort of my own thoughts (despite that scary dustup at the junction). So when I came around one last turn to the main street of Hope, I was surprised to see a big crowd of people outside of the Seaview Cafe. On Saturday night, you will likely find lots of people drinking in the bar and patio, reggae music playing, kids and dogs running around, campsites, bonfires, and people cooking meat in the yard. What the hell? I coasted in with a huge grin on my face. This was exactly what I needed. I was glad to set up my tent, get some bar food, and talk to the locals.

“Hey, you got out here on a bike? That’s pretty badass! Where ya headed?”

“Seward to Valdez.”

“Hell yeah!”

After a burger and two beers, I went outside as a local jam band started playing. I was exhausted from the day ride, and the food and beer just about knocked me out. I crawled into my tent and quickly fell asleep to the white noise of live music and local partiers. It was a happy place to be on this big, wild shoreline.

I left for Girdwood the next day. As the eagle flies, it’s 15 miles across the water. By road it’s 50 miles, and the first 30 of it is all uphill until you clear Turnagain Pass. I spent 4 solid hours beating my way to the top before descending back down to the edge of the ocean, 12 miles away from where I left it. Once I got to the westbound side of the highway, the tailwind blew me all the way to Girdwood. I could have opened a sail and coasted. Today, the wind is my friend in the fjord country.

Girdwood has a Forest Fair every summer, where Alaskans from all over the state come together to watch music, buy and sell art, celebrate, and be hippies. I was lucky enough to roll in during the last day of it. This town felt like a mini-Asheville.

A local woman who I met in Hope last night told me I needed to check out the band playing at 5:00. I went to the stage to watch them. It was relaxing after all the hours I had busted ass that day, but I soon got bored and left. They had a clear semblance of the Grateful Dead, whom I have never liked. Besides, I could smell funnel cakes from the food stands, so priorities. I sat down to eat one when I heard the band play a rocked out cover of Pancho and Lefty. That got my attention and I went back.

Later, I went to the hostel, a homeshare in the residential part of town. An old lady greeted me and showed me around. She let me hang up my tent in the back yard to dry. I sat on the back porch, and she came out and told me that the porch was off limits to guests. Okay. I moved to the front to eat while my tent dried. The daughter, who usually manages the hostel, came by for a few minutes to talk to her. From what I overheard, something was up. The daughter left. Then the woman told me uncomfortably that her friends would be coming back soon for a barbecue, and I had to move all of my camping gear to the front, and that the back yard is actually off limits to guests anyway. Awkward much?

Look, I get it if you want to make money out of your house, but get your boundaries sorted out, people. I was polite and did what she asked, but I won’t be going back there again. Not that I plan to go back to Girdwood anyway, but you know what I mean.

It was all grey skies and fireweed from here. I rode a solid 40 miles along the coast and got back to the city in the late morning. I had some extra time to sort out my gear and get my computer out to make sure everything was okay while I was gone. I checked my work email. Nothing from the customers. Good. No news is good news.

Later that night I stayed in a HI-Hostel in Spenard, where unlike the one in Girdwood, I was allowed in the back yard. It was the 4th of July, and they were having a barbecue. I met an old guy who had lived in his RV for 10 years, a man who met a lady in Florida on his bike 16 months ago and they have been riding ever since, a young girl from the Chicago suburbs working in Alaska for the summer, and a dude my age with a 3 year old daughter who knew she was the cutest person in the whole place. And then there was me, the guy riding his bike from Seward to Valdez.

We drank and hung out as bottle rockets echoed across the city. The Chugach Mountains turned purple in the late evening sun. Fireworks continued to bang into the night.

This story continues on the Glenn Highway.

Autumn on the C&O Towpath

Autumn on the C&O Towpath

“Autumn has a beautiful way of substantiating these lower moods and reflecting them in the environment as something vital and true. Darkness is as crucial to us as light—we can’t appreciate the sun without the shadow, or spring without the fall. Remember that and embrace your inner autumn and the feelings it encourages.” – Andrew WK

I’m becoming a big advocate for train supported adventures, especially since Chicago is a major hub for railroad transportation. Last year, Amtrak added a bike car to its Capitol Limited line, enabling cyclists to access the Great Allegheny Passage and C&O Towpath, a big rail to trail system between Pittsburgh and DC. I got my first chance this fall to try it out, and boarded a Pittsburgh bound line out of Chicago early Friday night. If things went as planned, I would get to the trail’s end at Georgetown, six days and 330 miles later.

Day 1: Pittsburgh to Connelsville

The train got into Pittsburgh at 6am. The days were getting shorter and it was still an hour before dawn. A huge rain system just blew over the area and was 20 miles to the east, steadily getting pushed away by a cold front that promised a week of brisk, clear autumn weather. I rode out of the city on a wet paved bike path that followed along the Monongahela River past several large steel factories. I crossed a bridge looking back at the city, which was still shrouded in fog. The air was damp and warm, and crickets echoed along the riversides, perhaps for the last time of the year. It was October in the mountains, and the bite of the cold season was imminent. I continued, holding onto the last fleeting moments of warmth and comfort. Onward, I cycled into hundreds of miles of foliage and cold mountain air.

I hit gravel in the next town and followed the path along the Youghiogheny through a hundred muddy puddles, throwing dirt all over my bike. Clouds lifted and brightened throughout the day, lightening the sky and its reflection on the river’s surface. The water was muddy and brown from unrelenting rainstorms. That was a good sign. I was going to paddle it tomorrow, and high water is good water.

I reached a KOA campground near the town of Connelsville and set up camp. From here, the track goes right through the middle of the range.

Day 2: Connelsville to Confluence

Morning fog shrouded the trail and I was freezing as I broke down the campsite in the dark. Normally, I would wait until the warmth of sunrise, but I had to get to Ohiopyle by 10:30. Dawn was breaking as I got on the trail at 7. As the sun met the mountains, fog lifted, revealing a million colors of foliage on the mountainsides. Every possible shade you could imagine of red, orange, yellow, and an occasional evergreen speckled the deciduous landscape. My dad told me once that although the alpine mountains out west are huge and majestic, he prefers the warmth of the forested Appalachians. I would agree. This feels like home.

I rode hard, trying to beat the clock to sign up for a river trip down the Lower Yough. As I neared the town, the roar of the river below and an occasional glimpse of rocky rapids between the trees promised a good river trip. I made it to the check in at 10, and bombed through some great rapids that day. You can read all about it here.

That afternoon, I rode on for 10 miles, drying off as I made for the town of Confluence. I got to a public campground an hour before sunset, hoping to find a bar to watch the second presidential debate. The bombshell video about pussy came out on Friday, two days ago as I was leaving on the train. A video of Donald Trump bragging to Billy Bush about how he’s a star who can get away with anything, which apparently includes treating women like shit. And here I was, in Confluence, Pennsylvania, trying to find somewhere to watch the second debate, two days after my Facebook feed turned into a circus. Strap on your clown shoes and let’s fucking do this.

I never did find a place to watch it, but the night was still eventful. I met an old veteran who was walking a huge push cart across the country, DC bound from Astoria, Oregon. He looked like an older Middle Eastern man with a full, dark beard and even darker eyes, and the wear of life and travel in his face. His cart was decorated with an array of stickers and signs reflecting his journey and message protesting our country’s thirst for oil. If I didn’t know better, I would guess he’s not fond of orange billionaires either. He pushed onward into the night.

Day 3: Confluence to Cumberland

I got going at sunrise because it was too cold to leave any sooner. It definitely got into the 30s last night. The gradient increased and the river to my left narrowed as I made for the heart of the pass. A town would appear around a bend every five miles and disappear a second later. I caught up with the veteran again at a bridge crossing the Casselman. He had already gone 8 miles since I met him late yesterday. This guy was a machine.

The trail came out of the river canyon at the town of Garrett, and from there I made a couple valley crossings toward the high ridge of the Eastern Continental Divide. Windmills lined the top of the ridge, slowly turning about on this quiet day as I set a hard pace for the top of the pass. I’m used to bigger, steeper hills. But since this is a rail to trail, the grade is always steady, never going over 2% at its worst. It was an easy push to the top, marked by the entrance to the Big Savage Tunnel.

Immediately on the other side was a fantastic view of the eastern mountains. Cumberland was just past the gap ahead. I made a hard descent for it and got into town right before sunset. From there, I would follow the Potomac all the way to DC.

Day 4: Cumberland to Hancock

After Cumberland, the C&O goes along the long, sweeping bends of the Potomac for 180 miles until it reaches DC. Though technically downhill, you don’t really notice on the nearly flat gravel terrain. Pools lingered along the trail from the recent showers, and I was trying to dodge them – mostly succeeding, sometimes splashing mud all over.

I passed a few ridges uneventfully until I reached the Paw Paw tunnel, an old cut into the mountain that is 3,200ft long. Unlike the others, this one was unlit, allowing a small passageway just wide enough for a person to walk their bike.

Halfway through the afternoon, I stopped for a break and noticed that my Achilles heels were starting to get sore. This could be a problem. Well, fuck it, I’m going to keep going.

I pushed into the late day, trying to ignore it. At 10 miles outside of Hancock, the pain was starting to get worse. This is all in my head, I thought. I have beaten pain problems before with the power of positive thinking, AKA, this shit isn’t real, I’m getting on with my life and don’t care what my doctors have to say about it. Nonetheless, each pedal stroke was met with mild pain.

I set up camp at a biker/hiker site 5 miles after Hancock. Disgusted with myself, I got on my phone and consulted the black hole of Google for medical advice. One of the first search results I got for Achilles pain was WebMD. In my experience, no matter what is wrong with you, WebMD will always narrow your situation down to one of two things: tendonitis or cancer. Fuck off. Then I found what I was looking for: cycling forums addressing the issue. My problem was definitely because of a bad fitting, likely that the seat was too high and needed to come down a half an inch. Okay. I’ll lower it and try again tomorrow.

Day 5: Hancock to Harpers Ferry

The pain backed off that night and I felt okay for the first 20 miles of the next day. It fired up again after I stopped in Williamsport. But as long as I rode steadily, it wasn’t that bad. Well, maybe I can just ignore the soreness and sing Weird Al Yankovic songs to myself to calm the monkey fight in my head. Cause I’m trigger happy, trigger happy every day (happy every day)! I did this over the next few hours as I rode along the peaceful bends of the Potomac.

When I stopped for a break at Shepherdstown, I looked at my feet. Shit! They’re getting swollen!

Well, I’m not going to positive think myself out of this one. Each Achilles was mildly swollen with limited range of walking motion. It wasn’t bad, but it could be if I didn’t back off. I called Amtrak and changed my ticket from DC to Harpers Ferry, the next stop 12 miles out. If I could get there, I could ice up and rest for an extra day before going home.

I got back on my bike and made for the hostel. This is a bad idea. But if I can get there, I can get the rest I need in the company of other travelers. Cause they’re my people.

I pushed for 12 miles, checking periodically to see if the swelling got any worse. It didn’t. The orange sunlight of the late day broke through the trees and the rapids of a steep gradient on the Potomac came into earshot. The town was getting close. I finally went up one last hill to the Harpers Ferry Hostel. I was glad to be done, 60 miles short of my goal and feeling like shit.

Day 6-7: Harpers Ferry

I rested, iced up my feet, and chatted with transient guests, mostly other cyclists on the C&O or hikers on the AT. This late in the season, I only met one guy still on the AT, who was making a hard push to get to Georgia before the bite of winter really hits the mountains.

Emily, a sweet backpacker from Britain was on a roadtrip in the states. I chatted with her about our adventures, our mutual love for Whitefish, Montana, and my crazy ideas of being a world traveler. And how it just might be closer to reality than I think. She had spent a few days in Harpers Ferry, hiking and horseback riding. If there’s one thing I know about equestrians – and this is because I have two of them in my family – it’s that they are serious about their horses. Tomorrow, she planned to drive north to see the autumn peak in Vermont.

She dropped me off at the depot in downtown the next day, maybe to be seen again, maybe not. It’s always sad to lose a fellow traveler, especially somebody as full of kindness and love for adventure as she was. But I suppose the loss of somebody is what gives worth to your memory of them. Perhaps in the same way that Andrew WK believes that the darkness of autumn is what allows us to appreciate the warmth and light of the spring. Perhaps the connections that I build with people couldn’t really exist unless there are times when they don’t. Perhaps I just need to “embrace my inner autumn and the feelings it encourages”.

My feet were still sore, but well enough to walk around. I explored the streets of Harpers Ferry, since I didn’t get to do that last time. Finally, I wheeled my bike onto the train, had an attendant rack it in the bike car, and slept into night.

“The bitter winds are coming in and I’m already missing the summer.” – First Aid Kit

The Shores of Kodiak Island

The Shores of Kodiak Island

…continued from the Glacier Discovery Packraft

Kodiak, the emerald isle of Alaska, is a lush, enchanting, and ragged island in the middle of a vast grey ocean. It is part of an archipelago south of mainland Alaska, remaining largely remote and unchanged other than a ring of coastal villages and fishing towns. There is one highway system on the northeast side of it that goes for 56 miles of rugged coastline, rendering the rest inaccessible except by boat or plane. I flew in from Anchorage for the weekend with my bike to see what this road was made of.

It was raining when we landed that afternoon with clouds of fog covering the steep mountains above the town. A cab dropped me off at the U-haul, and I noticed right away that this area doesn’t have the same wave of tourism in the summer as the mainland coast. It felt like a real, honest as shit fishing town. I’m going to like it here.

I loaded my bike box into a U-haul van, drove to a campground, set up camp after the rain backed off, and went back into town for supplies. But first, I needed a drink. The Kodiak Island Brewing Company looked and felt like an old saloon. And I bet if they ever read this, they’ll probably argue that they are a saloon. With a sawhorse bar and benches, the smell of old wood and brewing malts, and country music in the speakers, I thought that all it was missing was a layer of sawdust on the floor.

I got a big glass of something good and malty and talked to a few locals. To my left, people were talking about some guy they knew who caught a 100lb halibut yesterday. I figured a lot of fishing stories probably get back here.

After dinner, I went to the town Walmart to get supplies. But there was one important thing I needed to do first to truly feel like I experienced the ultimate. Several years ago, I read on a travel website that they have a bear in the Kodiak Island Walmart. And it wasn’t enough for me to see it in Google Images. I needed to find this bear in person, alive, for myself, and gaze upon its frothy glory. Once and for all, this would be the apex of all that was Kodiak to me. Everything else could have failed, and I would still be the winner. Traveler, give me a badge and a golden star, they do indeed have a bear at the Kodiak Island Walmart.

I left with my weekend supplies, proud of myself and all that I have accomplished.

Later that evening, the clouds lifted and all was clear, save the breaking fog on the mountaintops. I got on my bike and started for Anton Larson Bay, an inlet just over a mountain pass to the north. I made a steady, gradual climb uphill for 5 miles before hitting gravel at the base of the pass. My road bike is tough, but I’ve suffered enough dirty bastard roads to know that it wasn’t worth it. I coasted back down to camp and hoped for better luck tomorrow. But not without a quick side trip to Womens Bay. Because, why not, it’s nice out.

I set out again the next day, aiming to reach Fossil Beach, 40 miles and several ridge crossings south. Let’s see if I have the patience for 80 miles today. A blanket of stratus clouds had already enveloped the mountains again, promising to make this ride altogether more challenging. I rode back over the first hill to Womens Bay, crossed a flat river valley and made my first steep ascent up the other side. This seemed to be the pattern for the entire ride. Flat, wide river valleys punctuated by steep coastal ridges, winding rollercoasters, and unpredictable topography. Somewhere in the middle of it, fog and rain hit, limiting visibility to 50 yards. Waterproof gear, my ass.

After a couple hours of steady rain and steep climbing, I got to the Old River Inn, a lodge situated at the only road junction on the highway. I made it at noon, just in time for their restaurant opening. Some guy saw me and said, “Nice day for a ride, huh?” Yeah, it’s a real cracker jack of a day.

When I came back out, I was faced with a decision. I had 16 miles to go over one last big mountain pass to Fossil Beach, awesome though it may be, was more than I wanted to do in this shit weather. Should I head back? I weighed it, remembering other trips where I got focused and kept going, and it turned out to be the right thing. In this case, the clouds made my decision for me. To the south, they started to break and lighten the forests. Got it. Keep going.

The ride from there to Pasagshak Bay on the other side is 8 miles, and the meat of it is very steep. I pushed uphill for 30 minutes before breaking out of the tree line for a minute, and then plunging into maddening descent. Soon, I was back at sea level, passing horses and cattle ranches along the south shore. I’ll be damned if they have ranches out here.

I thought I was done climbing. No, there was more. Fossil Beach was on the other side of another ridge, and I had to clear another hard switchback at the start. For fuck’s sake. After that, the road went steeply up and down creek crossings, wearing me out. I saw the cliffs going out to Fossil Beach ahead, amidst gales of misty rain and the roar of the ocean. I had to climb yet again to get uphill from the shore, started, and at about halfway up I decided all at once, no. The glimpse of it looked amazing, but I don’t regret my decision. My imagination will do the rest. I turned back.

I got to my limit as I climbed back over the pass towards the highway junction and the lodge. I still had 30 miles of relentless climbing to go before I could dry off at camp and get to sleep.

When I stopped for food at the restaurant general store, I was getting out my wallet when a golden retriever came up to me, wagging her tail. I always like it when a dog comes out of nowhere and wants to be my friend. I didn’t know her name, so I named her Daisy. I came back out with a bag of Cheetos and a soda and sat by the entrance ramp to eat. When she heard it, she does what any dog does when they hear the rustle of plastic. She ran up to beg for people food.

I didn’t know this dog, and didn’t want to be some random jerk outside giving her food, so I kept eating. Sorry, Daisy, those are the rules. I tried to tell her this, and she just got more excited. At one point she went down the ramp, found a rock, and started nudging it with her nose. What the world is she doing? She picked it up, carried back, and dropped it right in front of me, and said with her eyes “Look what I brought you! Can I have a treat?” She’s definitely got the whole cute begging thing down. Sorry dog, you got spirit, but rules are rules. I’m sure it’s not easy being a dog outside of a lodge restaurant, but from the look of her, I’m sure they spoil her pretty well. I wished her farewell and got back on the road.

I rode across a flat valley for 3 miles before reaching the first of two big ridge systems between me and my tent. This one started at a 10% grade. As soon as I looked at it, I thought, fuck you. 20 minutes later, I was at the top, legs burning from a steady cycle on high cadence. It felt just like my gym back home. Once I made it, I had an epiphany. That for all of my bitching, so much of my grief can be dealt with by just eating more throughout the day. I wasn’t getting exhausted so often for reaching my hypothetical limit, but because I just needed more fuel.

I made it through the next few hours with renewed strength and good pace. The last few miles to camp were in a complete downpour. Let’s do this, you wild, ragged island.

Next morning, I tried to check in my luggage at the airport, only to find out that I couldn’t do it until 3 that afternoon. With the extra time, I drove up to Fort Abercrombie, a now decommissioned naval base and historic landmark north of the town. Many of its bunkers are still intact and it has a scenic trail system along the shoreline.

My favorite spot was along the rocky coast of Miller Point. I came out to one of the overlooks and look who I found on a spire thirty feet away.

I had just enough time for two pictures before he fired off an eagle turd. I started laughing, it spooked him and he flew off.

Soon, I was flying back across the Cook Inlet to Anchorage to start a work week, then bigger things on the mainland. But I wouldn’t say that I saw very much of Kodiak that weekend. Not even close.

If you like friendly Alaskan fishing towns, check out Kodiak, get a stouty beer, and try to stay dry. And you might even meet a friendly dog or two.

This story concludes on the Harding Icefield.

Cycling Petersville Road

I spent a rainy day resting in Talkeetna, a tiny forest town with a handful of cross streets and one general store with most of the supplies I needed. In the summer, it has large crowds of tourists, backpackers, and mountaineers staging to climb Denali. The hostel was just down the street from the airstrip, where flightseeing companies take tourists out to glacier landings, or drop off mountaineers and supplies at the Kahiltna Basecamp.

Some of the climbers stay at the hostel to work out logistics. That night, I met Alistair, a mountaineering guide who leads people up Denali for a living. I didn’t originally want to do it because of the price, but he was the one to convince me that a flightseeing trip over the range with K2 Aviation would be the best flight of my life. I figured he was right, and took him up on the idea. First, though, I wanted to do my bike trip up to the foothills.

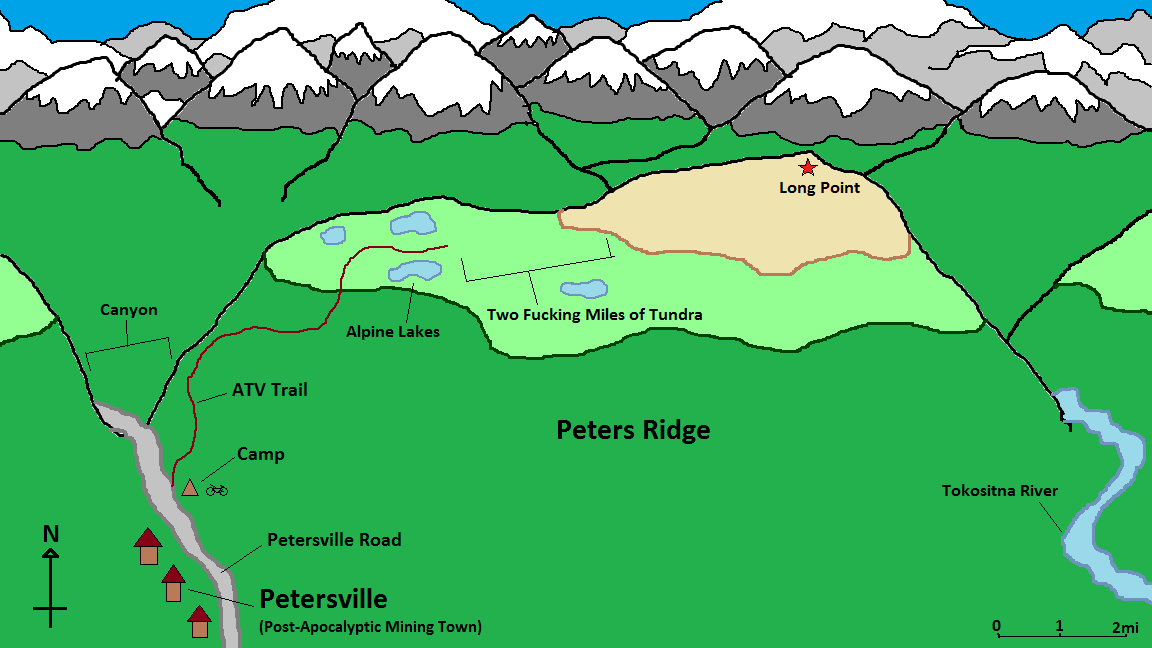

With 15 years of experience and a career based very largely on predicting Denali’s weather patterns, it was Alistair’s professional opinion that the rain would clear out late tomorrow, giving me a window of about 3 days to see Denali. So if I played this right, I would ride my bike for 60 miles from Talkeetna to Petersville tomorrow in the rain, hike out the next day to Long Point on the summit of Peters Ridge amidst clearing weather, come back to Talkeetna on the third day, and on the fourth, I would go on the flightseeing trip, yielding plenty of Instagram-worthy shots of the mountains like the self proclaimed Like-whore that I am.

I was game for all of it. As expected, the ride out from Talkeetna the next morning was one really long series of downpours. I rode 35 miles from Talkeetna to Trapper Creek, completely soaking wet. From there, I turned west on Petersville Road for mountains and hard times.

As the sole pathway into the south foothills, it once served as a road leading to gold mines dated as far back as the late 1800s. Now it’s mostly used by locals to hunt, fish, ride ATVs, or work the privately owned mines for their own killing. I was going out there to climb up to Long Point, the summit of Peters Ridge, which has an awesome view of Denali from the south.

After 10 miles, the pavement ended and I was sliding on fresh gravel. I could use bigger tires for shit like this, I thought, but I managed. Rain continued. The road mostly went through forests with a lot of steep creek crossings and gradual gain as I made for the mountains. The inherent raggedness of it aside, the road was well maintained in the summer.

The rain finally let up with 20 miles to go when a local guy on a mountain bike caught up with me. We talked for a while and he told me all about the nuances of fishing rainbow trout, none of which I can remember. He pulled off to a nearby cabin where he planned to stay and catch something tomorrow.

After a few miles, I descended a steep creek canyon and reached Petersville, an old mining town on the edge of the range. There were seven houses, only one of which appeared habitable. The others were dilapidated and boarded off – decaying before the backdrop of the ridges and dark clouds of the day, like a post-apocalyptic mining town. It was pretty sweet, I’m not gonna lie.

I came around a turn and saw the ATV track to my right, marking the climb I planned to do up the mountain. It was very steep and muddy from the rain. Anything short of a fatbike wouldn’t have a chance in hell of climbing it. And I couldn’t carry all of my gear in my hands either. All I could do was set up camp next to the trail and head up tomorrow with a lighter pack.

When I started the next morning, it was still cloudy but pleasant. I hiked up the steep face of the ridge as the valley behind came into clear view. Soon, I was hiking out of the woods and into the tundra. The trail wound about the steep curves of the high ridge, and was a lot tougher than I expected.

I got to a section of ponds, marking the first four miles of the hike. I tried to filter water here, but my filter got clogged yesterday at the creek next to my tent. It still worked, but would only filter a few drops at a time at a rate of 15 minutes a gulp. Two water bottles is enough for a day hike, right?

Soon, the trail faded into a field of spongy tundra. From here, I had to bushwhack across two miles of the ridge saddle with a few creek crossings and big willow thickets. I learned pretty quickly that the Alaska bush is no joke. It was continuous spongy, knee high tundra, hummocks, and creeks with 8 foot cut banks that won’t show up on a terrain map. It slowed me down big time. And this was just sub-alpine tundra; when you get down to the trees it’s even worse.

I hated to leave my tent at the bottom and venture into this. But the good thing was that I brought a SAR beacon with me on this trip. So if I did screw up and had to get help, I could use it to relay my GPS to a satellite and Search and Rescue, and get a chopper within the hour. One travel blogger who I follow had to do this in New Zealand after he broke his leg hiking in a remote canyon. His SPOT call got him out pretty quickly. It’s reassuring that I have a way to signal distress and don’t need to worry about getting Munsoned out in the middle of nowhere.

There was one last steep climb up to the high ridgeline and then two easy miles out to the summit. The mountains to the north came into view, huge and majestic. Clouds still covered Denali, but there was still plenty to see.

Finally, I reached Long Point, the summit of the ridge. To the north, the icy husk of the Tokositna Glacier curved around the mountains ahead for 30 miles before emptying into the moraine far below. To my right, the ragged spires of the Tokosha Mountains carved into the grey sky like razors. Behind me, the Talkeetna Mountains stood above a huge forest and the snaking bends of the Chulitna River. And far to the south, the Chugach Range and Matsu Valley loomed in the summer haze. I set up my camera for what ended up being a 90 minute shot (edited to about 5 seconds in post) of the mountains and fixed dinner as the clouds blew across the rocky wilderness.

It got to be late afternoon, and Denali still didn’t show itself. I knew that the weather was supposed to clear, but didn’t know how soon. I didn’t want to stay up there, exposed on the high ridge any longer and decided to go back. I trotted down the ridgeline and hacked back through all of that tundra and willow shit. I figured it out later that in that section, I was going one mile an hour.

Close to the end of the afternoon, Denali cleared. This shot reminded me of Stony Hill, the iconic vantage from the park road. Different side, same mountain. I scrambled up one last 30 foot bluff to a familiar rocky outcropping and got back on the ATV trail, leaving the high ridgeline for my tent.

I finally made it back in the mid-evening for an awesome night sleep under clear skies. It was the Summer Solstice, the shortest night of the year.

The next day, I was flying back on the road on a perfect bluebird morning. Several locals stopped to ask what I was up to – probably out of curiosity, and perhaps to make sure I knew what I was doing. Which I understand.

Rest assured, I know it’s tough country, and I don’t want to pull a Chris McCandless out there. I’ve spent years learning how to be as prepared as I know how to be. And like I said, I even have a satellite beacon for the added insurance. And, my dad always knows when I go out on something big, so yeah.

Soon I got to pavement, water, and cellphone service. I reserved a flightseeing trip for the first one out the next day. I saw Denali from both sides of the range. It was time to see it from the air.

This story continues in a little red plane.