The Alpenglow of Denali

The Alpenglow of Denali

“To the lover of wilderness, Alaska is one of the most wonderful countries in the world.” – John Muir

This was it. Denali, the park that changed my life forever. I obsessed over Alaska for four years because of that incredible mountain. I saw it for the first time in 2012, two days after the summer solstice. I remember cycling on the park road all night under the twilight of the Alaskan summer, easily the most backbreaking ride I’ve ever done. I climbed over hill after hill, hours beyond my threshold of exhaustion. I was getting schooled on what it is like to go beyond wherever your limits are, only to find out that you’re not even close to your goal. Finally, I cleared one last big hill to the first overlook, and saw Denali thundering into the morning sky, five times as high as I remembered in my dreams. It shattered my whole world. But little did I know that it would make me into what I am today: A traveler.

Since that trip, I have traveled as often as possible by train, foot, bicycle, or raft. And I’ve seen a lot of amazing places. But nearly every day for years, Alaska was on my mind. It was time to come back and finish what I started.

The first place to go on my trip back was Wonder Lake, a scenic area at Mile 85 of the park road. It is about twenty miles further than where I ended my trip last time. I originally planned to see it then, but was way too fucking exhausted to go any further than the Eielson center that day.

I boarded a Denali-bound train from Anchorage on a cloudy Saturday morning, got to the park in the afternoon, and camped at Riley Creek, a large campground by the welcome center. Early the next morning, I loaded my bike and gear on a shuttle bus for the Wonder Lake Campground, where I planned to spend up to a week waiting out the clouds, which more often than not will cover over the mountains. But if luck will have it, the mountains will eventually clear, giving me the pictures I had hoped to get four years ago. The north face of Denali and the majesty of the Alaska Range above a large open plain of forests, lakes, and rivers. This time I would get it – this time with better gear and experience.

The shuttle was full of backpackers who planned for days or weeks of hiking in the backcountry. As the bus went along the turns of the outer range, sheets of clouds and rain bombarded the mountains, clearing just long enough to reveal a fresh dusting on the high ridges. Occasionally, the driver stopped to point out moose our caribou walking through the tundra fields. I hadn’t yet adapted to the time change, and my caffeine addiction was killing me.

After a few hours, the rain backed off to occasional breaks of sun between the dark clouds. We got to the Wonder Lake Campground in the early afternoon, which sits on a hillside of tundra facing the Alaska Range, 20 miles to the south. I managed to find a campsite and set up about an hour before the next shower. From there, I waited out the bad weather for better fortune.

I hiked for a few hours on the McKinley River Bar Trail to the edge of the McKinley, a huge braided river that flows out from the north side of the range. The trail starts through about a mile of tundra, stream crossings, and kettle ponds before going through a dense taiga forest, and then stopping abruptly at a rushing channel of the river. From here, people who want to hike the further reaches of the backcountry will scout out the McKinley’s elaborate braid system and ford the shallowest channels they can find. Instead, I went back.

Later that evening, a ranger gave a presentation at the small amphitheater next to the campground. The life of a park ranger in Denali. He summarized the history of the NPS and the park, and told us what it was like to live out there every summer. Behind him, the evening sun lit up the forests under dark summer clouds, which still blocked the high mountains. That night, I slept under scattered showers.

I finally got my break the next morning. The clouds started clearing up, revealing the curves of Wickersham Wall against the blue sky. Soon, Denali and the sister mountains were in the clear, standing high above the countryside in resounding glory. The evening sun descended slowly in the north, casting alpenglow on the high mountains.

It was game time. I am going to timelapse the shit out of this. I got on my bike with my camera gear and rode a few miles out to Reflection Pond, a classic vantage point where many a famous picture of Denali has been taken and remembered. I set up my camera across the pond, programming the shutter to hit every 5 seconds as the orange glow of sunset left the mountain. Slowly, it blended from orange to pink, to lavender, to pastel blue, and then finally bright colors again in the early morning. All while a solitary duck swam around the pond. All while the park slept under the twilight of the summer night. All while my camera clicked away, burning, forever burning the landscape into memory.

At about 5, I took my camera to a hill next to Wonder Lake, another famous overlook a few miles away. By now, the Alaska Range was blazing in white under a crisp blue sky, and the park was waking up from one of the shortest nights of the year. The sun crested over the hills to my left, slowly casting light onto the trees ahead, while ripples of wind blurred the glassy lake below. This moment was every bit as glorious as I had hoped it to be. There’s not enough breath in a lifetime to fill that sky.

I loaded my bike on a shuttle bus a few hours later and rode 25 miles up the park road to Stony Hill. I spent the next few hours flying back out of the range and onto the open plain towards the campground, curving around the hills of the tundra fields. This was my favorite part of the park. While pretty much any mountain in that park could be its own postcard, the panorama here was by far the most dramatic. The outer range to the east, the Muldrow Glacier and Alaska Range to the south, and more kettle ponds and waterfowl than you could even begin to count. I was all out in it. It was so fucking awesome.

I got what I wanted. Finally, after all this trouble. Denali, the crown jewel of Alaska, in a rare moment of clarity. For the longest time, this was the holy grail of my whole traveling world. And I got it, finally, after four years of wanderlust. So when I got back to my campsite that afternoon, something unexpected happened. I wanted to leave.

How was that possible after everything I had put into this? I think some of it was definitely the fact that I felt like shit for lack of sleep. I was also starting to miss the comfort of showers, laundry, internet, red meat, and beer. I was getting sick of my backpacking food, and liked the mosquitoes even less.

But I think the bigger thing was that I felt like I saw everything that I came there to see. It was sort of like going to an art museum and eventually getting tired of looking at really cool art for two hours. Well, I guess I was tired of looking at Denali for hours and hours, as hard as that was to believe. Wonder Lake was every glorious thing that people had to say about it, but I was done. I took a bus back to the headquarters early the next morning and camped for the remaining days in the shade and comfort of Riley Creek. As soon as I got back, I went straight for the park restaurant for a burger of champions.

Riley Creek is a large campground in the shade of the forest, which was exactly what I wanted on a hot day like that one. That afternoon, I was in the middle of sorting out my gear when I heard a voice behind me: “Hey, you want to see a moose?” It was Allison, a woman from North Carolina who was visiting the park for a few days before a business trip to Anchorage. I agreed, and we quietly snuck 30 feet away from a female laying down in the trees. A minute later, its calf walked up to it, and they both wandered off. They continued to hang around the campsite for days, much to the curiosity and worry of the visitors, probably because the mother knew that predators tend not to be a problem at loud campgrounds. Moose are usually irritable and dangerous, but they seemed to know that the people around didn’t want to bother them.

Allison and I left early the next day to hike up to the Mount Healy overlook, which is a sharp 1700ft gain up the mountainside right next to the headquarters. It was a steep, exhausting climb up the face of the mountain and took hours. But we finally managed to scramble onto a bare, rocky outcropping and see a great view of the Nenana River Valley. To the right, the ridge system went on for 10 miles before it would slope downward to the Savage River. The very top of Denali could be seen above the mountains to the west, only a few hours before it would hide in the clouds again. The haze of wildfire smoke blew in from the valley to the east. Down below, the thin strip of the Parks Highway followed along the glimmering Nenana River.

We made our way back down the mountain, got lunch at the park restaurant, and Allison left on a tour shuttle bus to see the park road. I went back to camp. And for the first time in weeks, I did nothing.

The next day was our last one in the park, and we agreed on one last vitally important thing to see: The Sled Dog Demo.

These dogs are a very big part of the work that goes into maintaining the park. In the winter, rangers use them to access areas of the park where vehicles obviously can’t get to. They grow and train the dogs at the kennels close to the main headquarters and take them out on practice runs all summer long.

Three times each day, they have sled dog demonstrations, where a ranger comes out to tell large groups of visitors about the dogs and their history and use at the park. Then they bring out one of the sleds and have some of the dogs run a loop right in front of the audience. Whenever they do this, the dogs go completely nuts.

And finally, everybody goes over to the kennels to take pictures and pet the dogs. The rangers believe that socialization is a very important part of their training, and encourage tourists to visit and pet them. Cause after all, a social dog is a happy dog.

Allison and I agreed that it was a motherlode of cute. I mean look at those guys. They redefine badass. It was a good final note to end this chapter of our adventures. Soon, we boarded the southbound rail and shared a seat in one of the dome cars. Her exhaustion finally got the best of her and she passed out in the seat. I continued to watch the forests and mountains go by.

I got out at Talkeetna and she continued on her journey southward. The train rumbled and faded into the distance and all was quiet at the depot. I wasn’t done with Denali yet. I got on my bike and made for the hostel.

This story continues in the South Foothills.

Descent to Jasper

Descent to Jasper

…continued from Part 2: The Columbia Icefield

On a taco, kimchi marinated pork is pretty good. But when you dry it into jerky, it is fucking gross. You learn things like this when you travel. Just smoke the meat and be done with it, people. It doesn’t have to be this whole thing. I tried to eat it and decided it was way too revolting to get through, barring an actual survival situation. I had another bag of beef jerky, which didn’t taste as bad, but was another whole challenge to eat. Each piece felt like I was chewing on a leather belt. It was so tough that I actually lost time trying to eat just a few pieces. I threw both of those bags in the dumpster on my way out of the campground. So be it if I’m hungry for a few extra hours.

The road passes the Athabasca Glacier and the western edge of the Columbia Icefield, which can be seen along the edges of the mountains. The glacier’s terminus had almost reached the road at one point, but has receded about a mile up the valley. Up here, there are mountains with badass names like Mt. Andromeda, who had cut into the crisp morning sky under a waning gibbous moon. I stopped my bike at the edge of the moraine to get pictures, while a team of ice climbers went up the trail to the left on what looked like a day trip on the ice.

I enjoyed it all but twenty minutes and turned northward out of the pass. The climb to get up there yesterday was utterly backbreaking, and the descent down the other side was nothing short of sheer terror. Amazing places like this come at a cost, and I knew that all too well. At a 12% downhill grade, I plunged into the canyon, only able to slow down just enough to keep from speeding out of control. With thin tires, cable brakes, and loaded cargo, this felt like suicide. I watched for the river and forest to join with the road to the left, and for this horror to be over. After ten minutes – what felt like much longer – it finally was. The river met the road and I coasted the rest of the way out with ease.

Over the day, the road gradually leveled out, and the mountains became smaller and more distant as I raced against darkening clouds for Jasper, the final destination of the ride, for food, shelter, rest, bragging rights. But it was much better to be on gravity’s side out here. I had been cycling uphill for three days straight, and this was the first day with almost no climbing whatsoever.

Around 2:00, a car slowed down and stopped in front of me. A lady got out and waved me down. “Hey, did you happen to lose a sleeping bag? I found this along the road,” she said, getting out a blue Marmot bag.

“No, mine is in my cargo, but thanks.” She drove on, looking for its owner. I went on, feeling encouraged once again that good people like her are out here. She didn’t have to care about me, that bag, or whoever it belongs to, but she cared about all of it. With that kind of karma, she can have it for all I care. The clouds ahead were getting darker, and I needed to hurry. By then, I was feeling pretty ragged and worn out.

Later, I mounted my GoPro camera onto my tripod, which was strapped to the pannier rack, to get some reverse shots of the road behind. When I stopped to take the camera off, I realized that I didn’t fasten it very well, and it was one pothole away from coming lose and tumbling onto the road – all of my footage along with it – to be lost and forgotten forever. That could have been an expensive mistake. Like the Screaming Trees said, I nearly lost you, GoPro.

I finally made it to Jasper around 4:00, where I had to climb one last big hill along the mountain to my hostel. I was done with this, I thought, got off my bike, and walked it up for two miles, just as the summer rain hit the mountains.

There were a lot of international backpackers at the hostel, either on roadtrips or by the Via Rail train. Other people like me were passing through on outdoor adventures. A young lady Kaitlyn was a forest ranger from a provincial park somewhere north, who between shifts, likes to drive into the mountains to go rock climbing, and then just sleep at hostels or in her car. She noticed me locking my bike and carrying my gear in, and wanted to know what I was doing. We talked a bit about our adventures.

“Hey, are you hungry? I have some extra food in my car, and I know you’ve been out riding all day.”

“Oh I’m okay,” I told her. “I’ve been eating out of the vending machine. I was thinking of getting a meal sometime tomorrow when I get into town.”

“Well if you want, I’ve got some pasta in my car that you can eat,” she offered. Again, with all the good karma out here. Seriously, this is good people. My rule is that I don’t go looking for it, but I don’t turn away road magic when people offer it. We sat in the hostel lounge while I ate her food and traded stories with her and the other people at the table. I had been out busting ass for four straight days, and this was the first chance I had to clean up and relax.

My train out of town wasn’t due until mid-afternoon the next day, so that gave me time that morning to check out the Jasper Skytram, a gondola on the edge of town that carries visitors to the top of Whistler’s Peak. From there, you can hike the trail system and see a complete 360 degree panorama of the Canadian Rockies, including six mountain ranges, numerous lakes and rivers, and the town of Jasper, 3,600 feet below.

My hostel was a short walk away from it, so that morning I went up there and got on the first lift of the day. Trees glided by silently below as the gondola smoothly made its ascent up the mountainside. A young fellow was our tour guide for the next seven minutes. He gave us a short history of the town, the gondola, and some facts about the region’s flora and fauna, none of which I can remember.

The panorama at the summit was fantastic. And unlike other mountains in the range, Whistler’s Peak is fairly rounded at the summit, making for an easy hike around its trail system. I spent a good hour hiking around and taking pictures. Smoke from forest fires obstructed the far off mountains, so I had to focus on closer subjects. In this case, they were rocks.

The tram swiftly descended back down the mountain to the lower station, where I walked back to my hostel, got all of my shit, and coasted my bike down to the town.

Soon, I was heading west on a Via Rail train, traveling into wildfire smoke, passing Pyramid Falls, Mt. Robson, the Valley of a Thousand Peaks, the remote town of Kamloops, and nightfall. I was one night out from Vancouver, a cityscape on the edge of the wild.

This story concludes in British Columbia.

The Columbia Icefield

The Columbia Icefield

…continued from Part 1: Calgary to Canmore

I only had one tube left and was paranoid that it wouldn’t get me through the rest of the tour. So I slept in and headed to the bike shop later that morning. I hated to miss an early start, but it did give me an extra hour to get a timelapse shot of the Canmore Engine Bridge, a historic landmark in the town.

At the shop, I bought four more bike tubes out of paranoia, and a pressure gauge, which I should have had anyway. I got both tires inflated to the proper pressure and was finally ready to keep going. If I can’t get through the next 300km with all of this, I thought, then I have serious issues. I got back on the highway and headed northwest.

I was so exhausted and pissed off yesterday that I hardly took any time to enjoy the scenery. From Canmore, the highway goes northwest along the Bow River Valley between huge, majestic glacier-cut peaks – one after another – that thunder into the sky ahead for countless miles. No photograph can wholly capture how resounding and awesome they are to see. Carved impossibly high into the sky in formations of sandstone, shale, and ice, the Canadian Rockies are on their own terms. This is the big mountain country. These are the stone gods of North America.

I made it to Banff around noon and stopped to eat. It is a big tourist village that offers just about every outdoor sport you can think of. It looms under the giant massif of Cascade Mountain, creating a popular vantage point for tourists and photographers. Today was the 4th of July, and they welcomed Americans.

Castle Mountain, the most prominent peak of the day, came into view ten miles later as I traveled uphill against wind and gravity, with the rush of Bow River to my right. It was fresh with swift meltwater, and flowed southward, eventually going all the way back to Calgary. A man in a canoe went by. I pedaled on, happy to have the shade of light overcast. Any clouds would do in this heat.

I went on for a while to the continuous roar of highway traffic. After a couple hours, I reached the town of Lake Louise after a steady, hard pace on long uphill sections. I could have turned on a small side trip westward up a huge hill to see the iconic lake and vista that gives this place its name. Screw that, it’s getting late. From there, the Trans Canadian Highway turned west towards Vancouver, and the parkway went northward towards Bow Pass. I was glad to be away from all of the heavy traffic and loud eighteen wheelers. All was quiet on the road. The climb didn’t stop. It doubled in grade and went right into cold headwind.

The sun lowered behind the rugged peaks along the British Columbia border, and the golden Bow River snaked along the valley below amidst a darkening forest. Cold air blew from the high mountains ahead. I continued along the eastern ridge as the temperature quickly started dropping.

I made it to my hostel in the early evening, hours behind schedule but not really counting. The hostel, a series of rustic solar powered cabins, was the first of its kind that I’ve ever seen. I slept well along the rush of Mosquito Creek, not wasting any time getting any needed rest that I could. Another big day lay ahead.

My phone alarm went off at 4:30am and I set out at an hour later. The blue glow of daybreak illuminated the forest. A backpacker walked by me and towards the mountains, apparently also trying to get a head start. Soon, I was back on the road and climbing towards the summit of the pass. Clouds covered the tops of the mountains, and didn’t seem far off from this elevation. I began to notice the glassy dark blue claws of glaciers coming out between the mountains to the left. At times, the morning sun broke through the clouds, illuminating parts of the scenery. Other times, sheets of cold rain would seem to come out of nowhere. This was a volatile and dynamic place, where ultimately, the mountains decide how the day will be.

I was already covered in rain and was getting hungry. I had packed two bags of jerky, which I planned to use between food stops. The beef jerky was so tough to eat that it took twenty minutes just to chew through one piece. And the other bag had kimchi marinated pork, which I don’t know what I was thinking when I bought it – it tasted foul. I ate about as much of it as I could stand that morning, but ultimately chose to hold out until the next store. From the summit of the pass, I was about 10 miles of downhill away from the Saskatchewan River Crossing, which would probably have something.

It was a cold and shitty morning, but I finally hit the downhill section and coasted for a half an hour all the way to the river. From here, the highway reached a junction with a road going east out of the range. Still not entirely sure where to buy food, I crossed the river and kept going. Typically, highway junctions in the middle of nowhere like this one do have a place to eat. Like a gas station or roadhouse, or.. a freaking breakfast buffet? Out here??? Dude. DUDE! I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. A FREAKING BREAKFAST BUFFET!!! On a cold and wet morning, no less. It was like a cycling oasis. I rode up to the building as the smell of bacon coming from the kitchen reached my watering eyes.

I had four plates of eggs and meat, making up for thousands of lost calories. It was so awesome. I went on to tell the server how awesome it was, because I wanted her to understand how I feel. And I knew I needed it to power up for Sunwapta Pass, the ballbuster climb of the trip. I came back outside to my bike as a number of sightseeing tour buses were parked in the big lot in front of the building. This was apparently one of the main stops.

Several people wanted to know where I was headed, which I’m used to, then an Asian family wanted to get their picture with me. To them, I figured, a dude like me busting my ass out here – and really this entire place – was a completely new thing for them. Hell, I’m American and a lot of this seems new. I was fed, encouraged, mostly dry, and the sun was finally out. Let’s do this.

It started as an easy climb, following a braided and mostly flat floodplain along the Alexandra River. After ten miles, the road turned away from the river and went up to the base of the pass, getting worse with each pedal stroke. The mountains closed in and I was cycling up the canyon. Up ahead, I could see the monstrosity of the climb in clear view. Sunwapta Pass. A hard as shit climb. This was going to hurt.

The road quickly went to an 8% grade as I geared down and made a slow pace. I was moving just enough to comfortably pedal into the angle without falling sideways. I was sweating it for a whole mile before the road went flat again and turned to a big loop to the left. Out of breath and surprised at the reprieve, I coasted slowly around the bend and gathered my thoughts for a moment.

I caught up with three road cyclists who were touring in carbon fiber featherweights. A lot of cyclists like them do supported tours in places like this and have somebody shuttle their gear ahead. I, however, don’t feel like spending the money or time for that and prefer to carry all of my shit with me. It means I’m slower going, which is the tradeoff for the independence. Here, obviously, they were having an easier time.

After the loop is the meat of the climb, which goes for almost two miles of 8-12%. It is one monster of a grade. I fought my way up a few hundred feet, took a break, climbed some more, stopped again. I think I stopped about six times. It only lessened the suffering by notch. It was terrible. But the overlook here was a good distraction.

After it curves around the ridge, the grade lessens to about 5% for a while, which is well under my threshold. I don’t really like it, but I can at least work with it. I was finally nearing the summit, where I turned to find a site at a nearby campground. It was mid-afternoon, but I was definitely done for the day.

One thing I’ve learned from mountain touring is that the work and payoff are usually directly related. The rewards are big, but they come with a brutal workout. It’s either awesome or it’s a beating, depending on which side of the coin you’re looking at. It turns out that the summit of Sunwapta Pass, which is right at the edge of the Columbia Icefield and the Athabasca Glacier, is the most amazing part of the entire highway.

I had a few beers with an older English lady and her partner at the campground, and she told me I should hike up the nearby Wilcox Pass Trail to see the surrounding mountains and glaciers from a high ridge.

I spent an hour scuffling up the wooded trail and into high clearing along the edge of the mountainside. At the trail’s end, a lone red park bench sits in view of the Columbia Icefield, the Athabasca Glacier, and numerous other majestic mountains and icefalls. As the sun descended to the west, I imagined the vast snowfield ahead in an ethereal orange alpenglow amidst ragged, darkening peaks. The sunlight parted as the world ahead turned into shades of blue, and the temperature started to plummet. I made my way back down the mountain and to the warmth of my tent. Fucking hell. This place is unreal.

Everything else was downhill from here. And that was fine by me.

Calgary to Canmore: A Shitty First Day

So, Canada happened. But Juneau happened before it, and that was only because Burning Man did not. I tried to buy tickets to Burning Man this year after seeing all of the videos and pictures of the festival – its artwork and its people, its burns, its whole freaking aura – only to discover that a whole shitload of other people were thinking the same thing. Its ticketing system amounted to 2 million people all trying to buy 40,000 tickets in the time window the size of a golf ball. I missed my window by microseconds.

That left me an extra week to work with and decide on some other adventure, and hopefully something at least as good. It’s no secret that I’m obsessed with Alaska, so I looked for something there that I could fit in at short notice. I had never been to the southeast panhandle, which is a bit different from most of what I saw the first time further north. I added Juneau to my Canada trip on a whim, which was already booked and ready to go. So it was a week of glaciers, forests, big misty mountains instead of a desert metropolis. Burning Dan will happen another time. Screw you, ticketing system.

Juneau came and went in a blur of rain, ice, whitewater, and fog. But it served its purpose. Before I knew it I was loading my gear into an SUV cab and riding to the Juneau airport on an uncharacteristically sunny morning. I lucked out. There was hardly a drop of rain for both of my big days outside, which says a lot for an area where the locals don’t use umbrellas, but put on rain gear and learn to ignore it.

When I checked in at the airport, the agent spent 45 minutes trying to figure out what to do with my bike box. Clearly they’ve never dealt with a huge pie shaped bike box before. Hassle though it may be, it’s the only one of its kind that doesn’t screw up the brakes or derailleur, and doesn’t require me to remove the pedals, which are rusted onto the crank arms anyway. Plus, it has a wheel kit at the bottom, making it super efficient to wheel around. Honestly, it’s probably about as much as I can do to minimize the logistical pain of bike travel. In this case, I was a few minutes away from missing my flight, thanks to the extra attention from the attendant.

Four hours later, I landed in Calgary. By coincidence, it happened to be Canada Day, which was also the first of 10 days of the Calgary Stampede. Every summer, hordes of people come together in the city for parades, barbecues, and rodeos, and the city transforms into a huge festival of wild horses and the cowboys who chase them.

I didn’t care much about this, but I did want to see the downtown fireworks that evening. I made a few friends at the hostel and a group of us left to watch it along the river. The sky to the west darkened behind the red and white explosions, and I thought ahead to my journey out that way. I was two days out from my bike trip into the big mountain country. The Icefields Parkway of Alberta.

Later that night, I hung out in the hostel back yard with Melanie, a French backpacker who had spent almost 9 months traveling around the US and Canada, and was in between another short roadtrip and a job at a nearby cattle farm. These trips always bring interesting travelers like her across my path, who are just as interested in my adventures as I am in theirs. We had beers and talked for hours, trading stories of our time on the road.

Later that night, I hung out in the hostel back yard with Melanie, a French backpacker who had spent almost 9 months traveling around the US and Canada, and was in between another short roadtrip and a job at a nearby cattle farm. These trips always bring interesting travelers like her across my path, who are just as interested in my adventures as I am in theirs. We had beers and talked for hours, trading stories of our time on the road.

I spent the next day working out logistics that needed to get done before my bike trip. It took most of the day. I hauled the pie box out of the storage shed, reassembled the bike, took it to the shop to fix the wheel truing, packed my computer and extra gear into the box, and FedExed it to Vancouver. I had one week to get to it there, and as long as I did, my adventure would continue along the coast.

After everything was squared away, I was exhausted and needed a drink. Melanie agreed, and we walked into downtown to find some good bar food and whiskey to take the edge off. We sat down at an 8th Ave tavern, which for the Stampede seemed unusually quiet. When I asked the server about it, she said that the second day is the “calm before the storm” and then the next day is when it really begins to go nuts. She went on to say that people in corporate jobs will take off for the week and return to their old food services jobs during Calgary Stampede because they can make thousands of dollars. I could feel the energy simmering in the city. This was Calgary’s equivalent of Mardi Gras.

Next morning, I awoke to the rattle of snare drums and bagpipes from outside. A marching band was warming up for the parade, and it happened to be right next to my side of the hostel. As their drill leader hyped them up for the big day, the bagpipes were soothing to the nerves. This was it. I was hours approaching the open road. I would make it to downtown Jasper in four days this all goes according to plan. As Roland Deschain would say, there will be water if God wills it.

Melanie said goodbye, we agreed to stay in touch. Her time in Canada was coming to an end and mine was just getting started. I left with my loaded bike and rode through a city that was packed wall to wall with cowboys, vendors, and a huge parade of horses. There was no more holding back. This stampede was full on, as was a bike tour more than a year in the making. As I’ve already said, I didn’t really care much about this whole scene. I’m not that kind of cowboy. What mattered to me was distance, which I needed to catch up on due to a late start. Unfortunately, the entire square perimeter of downtown was blocked off to traffic and crowded street to street.

I finally found an underpass and went underneath the main arterial street on the south end. As I headed west, the god drums of the marching bands faded behind me and uncertainty lay ahead.

For a while, I followed the Bow River on a city bike path that went out to the beltway. From there, it got confusing. I needed to get onto the TransCan Highway, but there wasn’t bike accessible shoulder at that point. So I had to spend the next fucking hour going around side streets, pointlessly winding bike paths, and a suburban neighborhood before rejoining the highway and the big shoulder I was looking for. If it weren’t for Google Maps, it would have taken me even longer.

The road straightened across the open plain while the sun was poised brutally high in the sky. The price I would pay for sleeping in. I crested and descended rolling hills uneventfully for hours as the spires of Canada’s Rocky Mountains slowly came out of the burning haze and into clarity. There was one last chance gas station at the 22 junction, about halfway between Calgary and the mountains, to refill my already depleted water bottles. It was blazing that day in the ranchlands.

I continued up huge hills against hot headwind as flies landed all over my head and arms, crawling and buzzing in my helmet. At times, I could go downhill just fast enough to blow them off, only to have more land on me when I slowed down again.

I finally got to the edge of the mountains in the late afternoon, out of water and pushing onward to the next gas station to refill. To my benefit, the mountains blocked the sun from anymore of its punishment. I found a small pond next to the road to cool off. In that kind of weather, it’s the only bearable choice I have. I stopped at the first store I saw at Dead Man’s Flats, five miles from my campsite. I was almost there. Fucking hell, it’s been a day.

As I sat outside mowing down a gas station sandwich and Gatorade, I heard a pop and hissing sound come from my right. That’s a strange noise, I thought. Could somebody be using the pressure pump around the corner? It went on steadily until I noticed the rear tire of my bike deflate and the hissing stop. It just blew out of nowhere. Not from riding over glass or nails, or doing anything stupid. No, it just decided to blow out on its own. What the fuck???

Furiously, I took the tire off to figure out what happened. I found a big hole in the tube where it beaded into the one of the spoke holes and eventually blew. It was the result of an improper installation on my part and probably an under-inflated tube. So it was my fault, even though that didn’t make me feel any less angry.

I called the shop in Calgary that fixed the truing yesterday for advice (not their fault, I didn’t ask them to check the tires). The guy told me to install a new tube and work it under the bead all around, and reinforce the rim with electric tape, and it should hold. I nervously hung up and took his advice. Would this happen again further into the tour? Like say, when I’m flying down a mountainside? If so, would I crash my bike at worst and wind up stranded at best? And if I do get stranded, what then? These challenges all feel very real at game time.

Some local electrical contractors noticed me and offered a ride in their utility truck as far as Canmore. YES! That’s where I’m going! I loaded my gear into the back and rode in the back seat for the last 5 miles straight to my campground. It was encouraging to know that good people were around to help a traveler out, and that if things really did go south, that I wouldn’t be left entirely to my own agency.

All of the bullshit aside, I made it there at the planned hour.

I set up camp, fixed my bike, and walked into town to get supplies. The sky to the northwest blazed in orange and gold above the silhouette of Cascade Mountain, twenty miles ahead. It was a fair reward for all the trouble I went through that day.

I went to sleep in my tent that night, uncertain if my bike would hold out for the rest of the tour, and if I could really do this. There will be water if God wills it.

The Greenbrier River Trail

The Greenbrier River Trail

Many of West Virginia’s scenic river valleys are lined with abandoned railroad tracks that at one time served huge coal mining and logging industries, only to deteriorate and eventually be converted into recreational trails. The Greenbrier River Trail is the biggest of them, and a cycling destination that has been on my list for years.

It begins just north of I-64, following the Greenbrier River northward along river bends and rolling green ridges for 78 miles before reaching its terminus at the town of Cass. I arrived at the south end in my car at 9am on a Saturday morning with my bike and gear.

I planned to ride almost the entire trail in one day, stopping at a reserved campground near the northern end, and then looping back the next day to Caldwell on country roads. It was an ambitious plan at best, exhausting at the worst. But awesome no matter how rough it gets. I got my cargo out of the car, loaded it up on the bike and got moving. Right away, I hit a surface of crushed limestone gravel and paced for a long ass ride into summer morning fog.

Soon, the trail was busy with other cyclists and hikers, and an occasional horseback rider. The trail went along mostly under a forested canopy, only to break out into a scenic vista through the openings in the trees. By late morning, the sun angled over the eastern ridge and onto the Greenbrier River, which had more than its share of weekend paddlers, canoes, fishing poles, intertubes, and beer.

Beautiful, though a complete and utter pain in my touring bike. I pride my bike for the rugged steel husk that it is, but it had no suspension, thin tires, cargo, and this trail was almost entirely gravel on an upriver incline.

After 20 miles, the shock started wearing in my palms and feet, and I started feeling exhausted. I was out of shape and untrained, and hurt just about everywhere. Every mile hurt than the one before it, and I wasn’t even halfway there.

Hours and distance went by in a blur before I reached the town of Marlinton around mile 55. It was mid-afternoon and I was glad to see pavement again, if only for a few miles. Marlinton is the only town along the trail of any size, and is typically a stopping point by cyclists for its food and lodging. I was on a schedule and was hours behind, so I made a quick stop for water and then kept going northward out of the town and back into the woods.

With 20 miles to go, I pushed onward into the late afternoon, already way past whatever my breaking point was supposed to be. Everything hurt. My feet, my bruised hands, my neck, and my ass on the saddle. 16 miles to go. It felt like 160. After what seemed like an hour, I got to another milemarker. 14 miles.. 13.5.. a tunnel.. 12… AAAGH!!!

As I crawled along, the sun began its descent to the west, casting an orange hue on the eastern ridges. 5 miles left, by the gods. My body was screaming at me to get off and just walk the rest of the way. With 3 miles to go, I could hardly even pedal. I wasn’t even looking ahead anymore.

I finally reached the crossing road, turned left, and climbed up a small hill to the main building. I got this, but Fuck. Me. I am getting a BEATING.

Somewhere around here was a campground area. The main house was empty, there was one RV behind it that was also empty. An empty barn and stable. Houses along the road were also empty. Nobody was around. And I needed to find my campsite before it got any darker.

I pedaled further up the driveway and tried knocking on a few doors to ask people if they knew. Nobody answered. I was almost about to keep looking around the gravel driveways further up the ridge for this elusive campground when I spotted fire rings in the yard behind the main building. A hassle, but I found it (not their fault; I told the guy that I would be there around 5, and by 5 I meant more like 8).

I sat down in cool grass to eat dinner as a waxing gibbous moon rose above the ridge across the river like a sharp white stone in the lavender summer sky. It was a couple days shy of the Strawberry Moon, my favorite full moon of the year. Over the years, the early summer evenings always brought good times, whether they be trips or hanging out with friends. And a blazing moon would always rise in the east. To me, it is when my summer truly begins.

The rushing water below echoed across the darkening hollows and ridgelines of the river valley to the chorus of a million locusts. Mist gathered, creating a canopy over the campground, and the world faded into a well-earned dreamless sleep under the river fog.

I was two miles from the northern terminus of the trail and the town of Cass, the location of the historic Cass Scenic Railroad. From there, old coal fired locomotives take tourists into to the mountains all summer long. And just eight miles northeast in the next valley, the Green Bank Telescope Observatory has huge radio telescopes that tower above the campus, gathering radio signals and data from outer space.

I had been to both of these places as a kid, and planned to ride out to both again the next morning, only to forego that idea and head southward instead.

First, I was exhausted. Second, skipping them would mean getting back to my car around mid-afternoon instead of mid-evening. And third, the forecast was calling for late afternoon thunder. I could take a shortcut out to 92 and head south from there first thing, saving about 3 hours before storms began hitting the countryside.

So that’s what I did, heading eastward and then south on winding country roads. It was great to be on pavement again, even though I was out of shape and taking breaks every 20 minutes. One night isn’t enough time to rebuild overworked muscles, so I had to just eat it and keep going. I made it to White Sulphur Springs around 3pm, crossed the river, and finally got back to my car and the south trailhead. All with just enough time to air dry my gear before a huge, dark thunderhead rumbled in from the southwest. I drove straight into what was certainly one of many hard downpours to hit Appalachia that day.

The Greenbrier River Trail was beautiful, but I probably won’t ride it again anytime soon. I’m a few weeks approaching a tour in the Canadian Rockies, and I clearly have a lot of training to do.

Bikerafting the Shenandoah

It was my third weekend to do something adventurous, and I wanted to get in at least one good packrafting trip on a local Virginia river. In my area there are three: the Shenandoah, the Maury, and the James. Having grown up in the same watershed, as both streams from my family’s farm eventually get there, nowhere felt closer to home than the Shenandoah.

I decided to paddle the section between the towns of Elkton and Shenandoah, since both had accessible launch points. At first, I thought I could lock my bike somewhere near the takeout at Shenandoah, drive back to Elkton, float downriver to it, and then ride back. Then I changed my mind, broke the bike down, and strapped it to the bow of my raft along with my day cargo, and brought it with me on the river.

I had done a lot of trips with the bike or the raft, but this was the first time that I combined them. I had seen trip reports of other guys doing this in more remote places, and figured it was time to test the whole bikerafting idea myself. I pushed my bike-heavy raft out into calm water and paddled by a herd of cattle from a nearby farm. It was a bit awkward at first, as everything wasn’t entirely secure, but I managed. I didn’t have a full paddle range and needed to push the bike out further to paddle comfortably. That aside, it was fairly easy to get around in the water. And Alpacka rafts are more than capable of supporting that kind of gear.

As for the river, it was about what I expected. Most of the rivers in the valley are pretty tame, with Class I-II rapids spread out between big stretches of flatwater. The Shenandoah and the James don’t really pick up until they cut through the Blue Ridge Mountains, giving way to bigger Class III rapids and rock gardens. At the end of the summer, the levels were low, and navigating the rapids really had more to do with finding the deepest channels so I wouldn’t scrape over the riverbed. I had to get out a couple times to drag my boat over shallow areas. I went fairly swiftly on a gradient for the first five miles, which was great. The end stretch had a long, boring pool of two miles to the dam at Shenandoah.

I made it to the exit ramp after a couple hours, reassembled my bike, packed up my raft, and rode back to Elkton. Cause after all, I am nothing if not portable.

Packrafts can bring more options to your cycling expedition. Like me, you don’t have to let water stop you. They are rugged enough to get you and your bike across rivers, lakes, and even fjords. And they open up even more options, if like me, you like to run big rivers. You can ride out somewhere remote, stash your bike, and paddle down a whitewater run without the hassle of coordinating shuttles.

The biggest consideration I learned right away was that paddling with my bike and cargo greatly reduces its maneuverability. It is more than capable as a standalone boat in technical swiftwater, but I don’t recommend paddling with your bike and gear on anything higher than Class II rapids.

That, and touring with one will take some trial and error. My packraft and river gear add about ten pounds to my bike cargo, which I hate carrying on my back for very long. The top of the front or back pannier racks would be ideal for storage. Definitely be as ultralight as you can with the rest of your stuff, and keep in mind that a trailer won’t work unless you’re willing to go back and forth over a river, and that’s probably overkill. It may be worth it to ship the raft somewhere ahead of you, as I’ve done before.

Further information on the technique of bikerafting can be found here.

On my way back home, I pulled off the road for some good diner food at Thunderbird Cafe, solely because of the name. It didn’t disappoint.

Cycling the Skyline Drive

Cycling the Skyline Drive

I got back from Alaska two years ago, and ever since then, I have accumulated a ridiculous wish list of travel ideas. Hell, even today I watched some videos of places I’m thinking about diving in Mexico once I get open water certified. It turns out I discovered quite a few things to do around where I grew up in Appalachia as well. All this time, my own back yard was full of places to take my bike, raft, backpack, or some combination of the three. Once I realized this, I started researching and drafting routes of all of my trip ideas.

Most of the trips I was thinking about doing would take around two days, and since it wasn’t economical to go back and forth from Chicago, I would have to make Virginia my staging point and then use the weekends to go out. Fortunately, that was doable as a web programmer as long as I had an internet connection and a quiet place to work. I wasn’t going to take vacation time for this if I could help it. I flew to my parents house in the beginning of August, spent the work weeks getting through projects for my company, and used the weekends to make up for lost time in my home country. Four weekends to be exact, starting with the Skyline Drive.

As a scenic highway that parallels the AT along the Blue Ridge Mountains for 105 miles, the Skyline Drive is one of the best roads in the state for bicycling. It winds along ridgelines and mountainsides for the entire length of Shenandoah National Park, with great overlooks to stop every few miles.

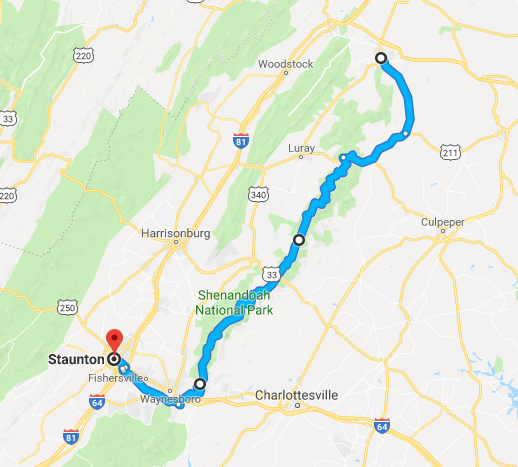

I had never cycled the drive in its entirety, but only the bottom half of it once in 2008 right before moving to Chicago. I flew in on a hazy evening earlier in the week, and my dad dropped me off at a hotel in Front Royal that Friday night, a mile from the northern terminus of the drive. I left early Saturday morning with overnight cargo. My plan was to get through it in two days, ending the second day back at my parents house in Staunton.

The first half of the day was almost entirely uphill, going from 600ft in elevation to 3,500ft at Big Meadows Campground, where I planned to set up camp for the night. The road was smooth and well maintained, although there wasn’t much of a shoulder. A lot of my time was spent surrounded by trees, only to break out into great, scenic overlooks of the Piedmont hills to the east or the Shenandoah Valley to the west. Other vehicles, motorcycles, and cyclists went by for pretty much the whole day.

Most of it was easy at my fitness level except for one place: the climb between Thornton Gap and Pinnacles. For 3.5 miles, I had to fight my way up a 5% grade between Rt. 211 and the Pinnacles Overlook. It would have been one thing if it were earlier in the day, but I had already been riding for four hours. By the time I got to the top I was wiped out, although the view of Old Rag Mountain was very party. Pinnacles was near the summit of the drive, and mostly went on level elevation along a ridgeline all the way to the campground. Nonetheless, I was exhausted, and my pace was as lazy as I could possibly make it.

I finally reached the campground in the late afternoon and got food at the lodge. When I came back to the camp, my friend Brent and his brother were setting up their tent next to mine. “Hey, what the hell you boys doin’ at my campsite!” They laughed and we spent the evening drinking around a fire and catching up on old times. I drank some bourbon that I bought in Front Royal and brought along in one of my panniers, as it’s important to travel light and not let anything go to waste.

The next day was almost entirely downhill, and mostly overcast with a few breaks of sunlight over the valley. I descended to Swift Run Gap and Rt. 33, then made my way for Waynesboro, going over negligible climbs and bigger descents. At the end, I went downhill for 8 miles all the way to downtown Waynesboro. From there, I pedaled westward on Rt. 250 like I had done a hundred times as a teenager.

Whether by vehicle or bike, the Skyline Drive is a great scenic highway to travel. It is well-documented on its NPS website, and has mileposts for its entirety, making logistics pretty straightforward. On a bicycle, it is mostly easy as long as you’re in shape, though the southward climb after Thornton Gap is a pain in the ass. And if you’re not in shape, it won’t be easy but still doable.

Check it out and see the panoramas for yourself.

APA Roundup: Packrafting the Flathead North Fork

I have had my packraft for two summers now, and it’s one of the best toys I have. I couldn’t even say how many times I’ve taken it out on the city rivers in Chicago. Whenever I’m not on Google researching ideas for bike tours, I’m doing it for river trips. I have come to find that paddling down a river, a wild one especially, is one of the most engaging ways I can take in the beauty of an outdoor experience. So naturally, I wanted to incorporate it into my Montana trip. Luckily, there were already quite a few people out there who were into the same thing.

Packrafting has already been picking up out west over the last ten years or so, and has developed its own niche in the paddling community. As it grew, the most active among the paddlers joined together and founded the American Packrafting Association in October of 2012. Along with bringing the community together, their focus has been on education, swiftwater safety, wilderness conservation, and river access. Lobby efforts have been done to legalize the sport in Yellowstone, Grand Teton, and Grand Canyon National Parks.

This year, they had their first ever roundup, drawing packrafters from all around for a weekend of paddling, workshops, swiftwater rescue training, and presentations focused on their current river conservation efforts. The organizers booked the weekend at a group site at Big Creek Campground, right along the Flathead North Fork. They planned day trips for everybody on that river and others in the park, depending on a person’s experience level.

I was planning logistics for my tour through Glacier around the same time I got the notice for this event, and when I realized it was right along the way, I added it to my tour dates. I wanted to take my raft on a challenging river again, but knew that running Class II-III whitewater alone was pushing it at my experience level (a lesson I learned the hard way on the New River last year). But I knew that these trips would have a guide and other experienced packrafters who I could learn from.

So I rode my bike to the roundup at Big Creek after hauling my ass over the Sun Road, locked it on a tree, set up camp by the river, and planned to spend the next day on the water. Moe Witschard, the main organizer, let me ship my raft and paddling gear to his house in Bozeman and agreed to take it to the roundup so I wouldn’t have to carry it with me on my bike. Cool guy.

I got up the next morning and unpacked the boat, ready to hit some good splashes on the river with my new friends. The organizers split us up into three groups, based on our experience levels. I was placed in the intermediate group, seeing as I wasn’t completely clueless out there, but certainly didn’t feel ready to run the big stuff with the best of them. Not yet anyway.

Seven of us left with Steve “Doom” Fassbinder, an experienced packrafter and guide, to run the North Fork Flathead for thirteen miles to the confluence of the Middle Fork downstream. It was a big river, about 200ft wide and moving swiftly at a high gradient. Even the calm sections had enough power to pick you up and take you away. Most of the rapids were rated Class II-III with a lot of splashes and wave trains. It was fed primarily by alpine meltwater, giving it a clear jade color.

Our group got our gear together, inflated our rafts, and got in right by the campsite. We pushed out from shore and each went flying down the river. As we went through the calmer sections, Doom taught us some of the basic maneuvers, had us practice self-rescue, and explained how he was able to read a set of rapids and find the right line. We spent the morning paddling through a number of choppy wave trains and turning out frequently to calm eddies along the riverside. But we all had a great time hitting wave after wave. People fell out here and there, but since there weren’t many hazards around and the water was deep, recovery was pretty easy.

Later that morning, Doom had us all eddy out at one point to surf a set of playwaves. Other rafters went out ahead and surfed the waves for a moment before either flipping or washing out of the rapid. I finally got the courage to try it, paddled upstream against the wave train, and then got distracted. Julia was paddling right in front of me when her boat flipped. She went right under my raft, I felt her head hit the bottom. She took a mouthful of water and came up six feet away, yelling for help. I started towards her. She got herself together and yelled “I’m fine! Get my raft!”

I turned around and paddled for it, easily catching a grab loop (and making me wish somebody was around to do this when I wiped out on the New River last year). Got it! …what the hell do I do now?

I was out of the rapids, but still flying down the middle of the river. I couldn’t paddle without letting it go, and it was too big to pull onto my boat.. Shit! Think for fuck’s sake!

I turned back upstream, put it ahead, let it go, and carefully ferried to shore with it bumping against my bow, a technique I came to find out later was called Bulldogging. I got it to a calm eddy and got my feet on the ground. Julia came over a minute later, out of breath and happy to have her boat back. It was my first river rescue. Go team.

We stopped downstream a while later at a shaded outcropping for lunch. Moe’s group caught up with us and we all sat on the riverbank with our colorful boats, trading rafting stories and shooting an array of interesting shit. Many of these guys have been on some amazing expeditions all over the place, and couldn’t bore you if they tried.

Eventually, we went back to our boats and eddied back in to continue the run. I was the the last one to get back in, and the only one who didn’t ferry out far enough to miss a large log sticking out thirty feet down. Luckily, it didn’t have any branches, but it was coming right for my face as I moved right at it in the current. I ducked backwards as it brushed over my bow cargo and nicked my helmet. With the sudden weight on the stern, my bow flipped and I got a face full of cold, dark mountain water. I kicked my way out from under and grabbed the bow line. Before I could think about self-rescue, I went right for a calm eddy, where I kicked to shore and recovered my breath on a rocky outcropping.

The rest of the day went smoothly, as the rapids got more and more peaceful. We finally ended our trip at the Middle Fork confluence, and celebrated with some ice cold beer.

We joined up with the other groups at the campsite that night for a huge cookout with plenty of beer, meat, and good food. Afterwards, a couple of speakers shared their experiences working with legislators and park officials to legalize paddling in various parks, and prevent the use of dams in different river systems. A couple of guys from Tasmania did a presentation on the Franklin River, where packrafters were successfully able to halt a dam construction project and preserve its pristine beauty. It was all really cool, but my exhaustion had finally caught up with me. I had a massively bad splitting headache, and I was feeling tired out from the last weeks worth of nonstop exploring.

I crashed hard and slept harder.

When I got up the next morning, the groups were gearing up for another good day on the water. The beginner level planned to do the same run that my group did yesterday, and my group was preparing to hike somewhere north for several miles and hit a more technical section of the river. I wished them luck and left the campground with my loaded bike, turning southward on a shitty gravel road towards Whitefish.

I hate gravel. My touring bike is durable enough to handle it, but it doesn’t maneuver for shit. And on this road it was even worse because they just poured new gravel on it. I had to go painfully slow, especially downhill, to keep from spinning out and falling sideways. It was two hours that I don’t care to go through again.

Eventually I hit smooth pavement and had an uninterrupted ride all the way to the Whitefish Hostel. I’m sure by that point I had to have smelled like fucking apple blossoms. So I put my bags down, took a gloriously hot shower, and slept like a king for the rest of the afternoon.

I had two days to relax. And unlike my tour, which I planned down to the numbers, there was no agenda. And that’s exactly how I liked it.

Glacier National Park

Day 1: East Glacier

I woke up somewhere in the mountains west of Whitefish. Looking out, the rolling hills passed by, and an occasional lake appeared. It was 7am, and I needed coffee. We were four hours late, thanks to a delayed connection in Spokane. But I didn’t care. Coffee was all that mattered.

I had left Portland the night before in the late afternoon, passing by the Cascades and into the deserts of central Washington. I had taken my bike up to some high places and saw some great parts of the northwestern country. But it was behind me now, and bigger challenges lay ahead.

I approached Glacier National Park, the location of my second bike tour on the trip. I planned to tour the Going To The Sun Road, a world famous road that winds treacherously along high mountainsides and through the middle of the park. It draws multitudes of tourists, backpackers, and cyclists every summer. Its panoramas are out of this world, and I finally had my chance to see them.

I planned to ride it from the east, starting in East Glacier, 30 miles south of the St. Mary end of the road. I would spend the afternoon of my first day there getting my bike and gear back together, and then leave the next day on a half day ride northward to the St. Mary Campground and the edge of the Sun Road. Then I would spend another day going through the mountains to the western side of the park and pedal out to Big Creek Campground, spend the next day packrafting down the Flathead River, and then end the trip with a short ride to Whitefish.

The train dropped me off in the late morning with my bike box and loaded backpack, which I had to haul across the road to the East Glacier Lodge. My friend Tim recently moved there from Chicago, and worked in the lodge restaurant. He let me crash in his dorm in an extra bunk before my ride the next day. This gave me the afternoon to unpack my bike and get my gear together.

I spent two hours outside of the lodge assembling my bike and organizing gear when I gave it a test run and shifted to slipping gears. I tried turning the barrel adjuster, which has done the job before. Didn’t work, as the derailleur indexing was altogether out.

I should know how to do this. There is a way to change the position by turning the screws. But I don’t remember which way, and this was not the time to really mess something up. I needed it fixed and ready by the next morning.

I made a quick phone call to a bike shop in Whitefish, rented an SUV, threw the bike and my extra baggage in the back, and drove for two hours in the mountains to get it fixed. This wasn’t entirely a waste, as I still had to get my bike box and extra stuff to the hostel there anyway, and this would eliminate the hassle of shipping. So there’s that.

I got to the shop late in the afternoon, and they were glad to take a look at the bike, even though they were way behind on other orders. I dropped it off and went to the hostel to leave my bike box and extra gear. They let me put my stuff in one of the back rooms for the next few days, which was supremely helpful. I sorted out everything that I wouldn’t need to tour, put it in the box, and left it in the back of the building.

How convenient that I was as stressed as I was and right down the street from the Great Northern Brewery, because their Huckleberry Wheat Lager was as delicious as last time. I got a glass of that and a BLT from the kitchen. I was almost done eating when the bike shop called to let me know that my bike was ready.

A well-earned shout out goes to Glacier Cyclery and Whitefish Hostel for helping me work out the details when in a bind. I won’t hesitate to deal with them again, and recommend them to anyone going through that area. I picked up my bike and headed back on a two hour drive to East Glacier, where I dropped the car off and rode my bike back to the lodge.

I found Tim, who was getting a team together to play Ultimate Frisbee in the front lawn. It was the first time I had played a sport like that in years, and I was surprised at how tired I got, despite everything I had done on a bike so far. Our team got whipped for two games, but it was a good time. We finally quit when the sun set behind the western mountains.

Four of us went to the lodge balcony and watched the sky turn red above the huge rugged mountains of Glacier’s eastern edge. It was good to finally relax after my shitstorm of a day. I polished the night off with a glass of bourbon and went to sleep in Tim’s dorm room.

Day 2: St. Mary

I left early the next day for a 30 mile ride northward through the foothills to St. Mary Campground, right by the entrance to the park. There were a few long, steady climbs under the hot sun, but nothing too bad.

The flies were the bigger pain. They flew around me whenever I couldn’t ride fast enough to outrun them. Whenever I got to a climb, they started to land on my arms, legs, face, in the vent holes of my helmet, one even got under my sunglasses. In the middle of one climb, I batted at one, lost my balance, and crashed on the gravel off of the shoulder. I was going too slow to cause any injury, but I scrambled back onto my bike feeling pissed all the same.

I reached the hills above St. Mary after a few hours. For miles around, countless rolling hills bore the scars of a huge forest fire, likely caused by thunderstorms. Though the woodlands were gone, the countryside nonetheless was vast and beautiful. There is no question that Montana brings with it a tremendous sense of openness and solitude. I descended down a steep hill to St. Mary Campground, checked in, and set up camp along the edge of the range under a blazing mid-afternoon sun.

I went to sleep just after dusk that night. An hour later, the wind picked up, and my eyes snapped open at the sense of lightning flashes outside. Thunder was coming.

I got out and saw a huge thunderhead passing ten miles north. The light of dusk illuminated it from the west, and the rest of it glowed in sight of the rising full moon, flashing and flickering soundlessly into the night. Gusts of warm summer air blew across the campsite, though the storm that caused them was too far away to cause any trouble. To the south, the full moon broke through a band of clouds just above the silhouette of Curly Bear Mountain. Small moonlit clouds raced across the sky above as the night darkened, with stars appearing more and more by the minute.

I see a lot of memorable things on my trips, but there are times when even the best of them don’t come anywhere close to this. On that night, the sight of a giant thunderstorm rolling across an alpine wilderness was a truly otherworldly thing to behold. Unfortunately, I didn’t watch it for long. I needed to get my rest for the next day. I got back in my tent and fell asleep to the rustling wind, which blew against the tent all night.

Day 3: Logan Pass

It was game time. I packed up and got moving on the Sun Road at 9:00. It quickly met St. Mary Lake, where it went on for 9 miles. It was mostly flat riding near the lakeshore, with a few negligible hills that I cleared whenever turning towards the mountains to my right.

I recognized all of the places where Jack Torrence drove his family on their way to the Overlook Hotel. I see why Stanley Kubrick picked this road for these shots, and respect is due.

Halfway along the lake, I hit gravel. A girl at the East Glacier Lodge told me that crews were working on the road for 8 miles or so up the east side of Logan Pass, and to expect gravel for the whole thing. Shit. That I did not want to hear.

It was already a hard climb just to get up to Logan Pass. At a 6% inclide, 2,000ft elevation gain, the uphill fight lasts for 6.5 miles. Trained or not, it wouldn’t be easy. But with a gravel stretch for the first four miles of the steeper section, it would be even worse. I looked ahead for the smoothest parts of the gravel road and steered accordingly, usually along the tire tread of the vehicles.

As I approached the pass, the mountains on the far end of the lake seemed even bigger and higher, covering half of the morning sky. The road steepened and turned gradually to the right around Going to the Sun Mountain. This was it. This was the climb. All of the buildup, the hassles, the training, all of that shit. This was what all of my busting ass had come to. It came down to this. Getting through this climb with my sanity, and making it down the other side with my bike in one piece and a story to tell.

I shifted down and slowly pedaled over the dirt and pebbles, looking out at the vistas to the left whenever it was okay to look away from the road. Before very long, the forests disappeared below, and the peaks of Little Chief and Citadel Mountains stood resolute on the far end of a terrifying ravine. I pushed onward, shaded by the trees to my right.

The dirt road finished its turn around the mountain and made straight for Siyeh Bend, a switchback over a small stream between Going To The Sun and Piegan Mountains that marked the second third of the climb, the end of the gravel, and a good place to take a break. When I finally hit pavement again, it felt like a luxury.

I stopped at the overlook, and like the climb up Mt. Hood, was a bit surprised at how much easier it was than expected. Even with cargo, even with gravel, even with a hot alpine sun, it wasn’t that bad. I took a break, feeling pretty good about the two miles I had left. With the help of pavement, I would kick its ass for sure.

I got going and shifted a couple gears up for a smooth pace all the way to the summit. What the hell? It wasn’t supposed to be this easy. It was mildly irritating.

But I made it, and had time to relax.

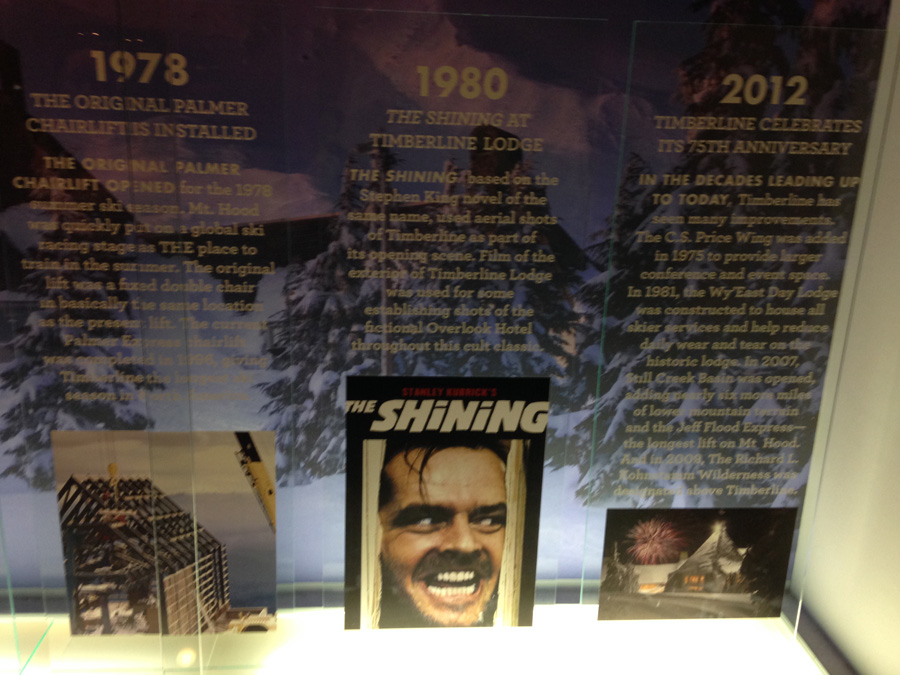

At the top of Logan Pass is a big visitor’s center that is swarming with people in the summer. Inside, they have a few exhibits about the park’s key landmarks and history (disappointingly, nothing about The Shining. You could learn a lesson from Timberline, Glacier National Park), and presentations by the park rangers. I wasn’t really interested in any of this, but I did want to see Hidden Lake, which requires a short 1.4 mile climb over the pass above the visitor’s center. The rangers let me leave my panniers safely in their break room, which was cool of them, and I started climbing up the trail.

What I didn’t realize was that even though it was the middle of the summer, and the alpine sun was blazing on the mountainside, the snowpack was STILL THERE, and was taking forever to melt. Almost the entire trail, a wooden walkway that can be easily traversed when you can actually SEE IT, was covered in snow. I did something that I don’t recommend, and hiked it wearing Keens and wool socks.

Every minute or so, snow would pack into ice under my feet, freezing whatever it could through the layer of wool. It was never cold enough to cause any worry, given that the wool insulated just well enough, and there was the sun helping to thaw my feet out from a horrible angle in the sky. I scrambled along, with sandals slipping every few steps up the snow, and the glare of the ground turning pink in my vision, thanks to my losing my sunglasses yesterday in St. Mary.

It went on like that for a shitty hour. I finally made it to the wooden platform and lookout to the lake. Disappointing. The small valley and lake were still melting in snow as well, and it just looked like a slushy mess. I figured it would look a lot more picturesque later in the summer, but for now, was way off on the cost/benefit ratio. But hey, how could I have known if I hadn’t gone out there, right?

(Actually, I stand corrected in hindsight. I just went back and edited this panorama, and realized the extent of my mistake.)

I walked, trotted, and slid down the snowpack for another hour before finally getting back to the visitor’s center. It was time to get my stuff and get going. The western end of Logan Pass descends at the same 6% grade as it does coming from the east, the key difference being the distance of the descent. It goes farther down, dropping another 1,000 feet in elevation before reaching Lake McDonald and the western side of the park. So whether you climb from that way, or you descend it, you’re going for longer. That aside, it’s pretty much the same.

Passes like this pose two big challenges to me: First, getting up to the top of them, and second, flying back down without crashing and busting my crazy ass on the side of a cliff. I made it up there easily enough, but knew that getting down the other side would mean a steep descent along the twists and bends on the vertical face of Pollock Mountain.

I got started downhill behind a car and a utility truck in front of it. We quickly descended out of the pass and started winding along the mountainside, going past waterfalls and streams of fresh snowmelt. Mt. Oberlin stood high across the canyon to my left in resounding magnificence. Before long, the view down McDonald Valley opened to the west in a forested carpet, fading into the haze of the afternoon.

I continued flying down the turns and bends of the Sun Road, amazed that I could keep up with the cars in front of me. I realized that vehicles on this road were pretty slow going. And at that descent, I was obviously going faster than usual. I went by the Weeping Wall, a spot where small waterfalls pour onto the side of the road, and got a fresh spray of mist in my face. I didn’t care. I was having too much fun.

I chased a car around The Loop, the lone switchback on the western side, and descended two more miles through forests to McDonald Creek and the end of the grade. From there, it was smooth riding all the way to Lake McDonald.

I was surprised at how smooth, driveable, and bikeable the road was, gravel aside. I guess if the state spends millions each year to keep it open, it better be. It is certainly one of the best roads I have ever seen on a bike, and I was satisfied that I finally got the chance to ride it after more than a year of buildup.

But the day wasn’t over yet. I still had to ride another 30 miles to Big Creek Campground, and I was in no mood to do it. I went along Lake McDonald at a worn out pace for 10 miles, turned north at Apgar Village to Camas Road, climbed for 45 minutes uphill, then descended the same distance down to the Flathead River. From there I turned west, and pedaled a final shitty three miles in gravel to Big Creek, checking in a couple hours before sunset. That night, I slept well by the rush of the Flathead North Fork. I was wiped out, and needed all the rest I could get for what would certainly be a big river trip the next day.

Cycling Mt. Hood, Oregon

Cycling Mt. Hood, Oregon

I like to map out bike touring ideas in my spare time, and had my eye on Mt. Hood, Oregon for a while. Large, dramatic mountains like that one always stood out to me, especially when planning bike trips along the nearby highways. And on the northern end of it, the Columbia River Gorge is recognized by many people as one of the “Most Scenic Rivers in America”. Also a great place to ride. It made sense to plan some kind of tour that would include a climb up the mountain and then a ride down the side of the gorge along the river, starting and ending the trip from Portland.

But the bigger thing that got my attention when I was poring over this idea was Glacier National Park, Montana. I’m a lifelong fan of the Shining. It is a cult horror masterpiece that I never get tired of watching, one reason being the outdoor shots of the mountains surrounding the hotel. I watched it one evening last year and remember thinking that the opening sequence looked strangely familiar. The small island in the middle of the lake, the big mountains to the left, the winding road through the forests and alpine mountainsides, were not of Colorado where the story takes place. They were along Montana’s famous Going To The Sun Road.

I looked up the filming location online. Sure enough, it was the same spot that I was already scoping out for a bike tour. I kept reading and realized that the Overlook Hotel at the end of the opening scene wasn’t in Colorado either, but in Oregon. The Timberline Ski Resort on the south face of Mount Hood. Perhaps I could bring Montana and Oregon together, tour both of them back to back, and by doing so, pay a homage to the opening sequence of the movie.

It took a lot of logistics, planning, trial and error, phone calls, and hassles, but I did it. I left on July 3 on an uneventful flight into Portland and stayed with my friend Alison, who lives in the Northeast Side. We hung out with her friends on the 4th, and I left early the next morning on a train to Gresham, a suburb west of the city.

Day 1

I planned on looping around the mountain, making Gresham my starting and ending point. It would take three days to do, the first being entirely uphill on the Mt. Hood Highway for 32 miles, where I would meet up with Alison and her boyfriend at a campground. On the second day, I would continue climbing to the town of Government Camp, which sits on the south face of the mountain, and then ride six painful uphill miles at a 6% grade to Timberline. Then I would come flying back down and continue around the side of Mt. Hood, and descend for 30 miles to my hotel in Hood River. On the third day, I would follow the river back to Gresham along the Columbia River Gorge and take a train back to the city.

The train reached Gresham in the late morning, and I got moving at a good pace out of suburbia and into the great forests of northwest Oregon. The sun had a halo as it moved along behind a thin band of overcast, but it was shaping up to be a sunny day, and a sunnier weekend. Out ahead, Mt. Hood appeared as the road wound about towards it.

After an hour, I started going uphill. It was easy climbing, but I knew that volcanoes get exponentially more and more shitty as you go up the face of them. I found that out the hard way in Hawaii. But I was determined not to let that happen this time. I had spent the entire month building up to this trip on a spin cycle, training my ass off. The buildings, side roads, homes became increasingly sparse, the grade got worse, and I climbed up the mountain between rolling ridgelines in the midst of a vast evergreen woodland.

I remember the forests of Oregon. They’re big. Everything about them. I knew that because I had hiked a manly 20 miles in Forest Park before in the winter, when clouds were low, casting drizzle and darkness on the trail. The woods were tall and thick, and moss seemed to engulf any trees that weren’t big enough to outgrow them.

There weren’t any clouds out this time, as it was the dry season of the northwest. But instead, the blazing sun stood high in the sky, and got to be quite horrible by the early afternoon.