Maui – Day 1-3, Haleakala and West Maui Mountains

Maui – Day 1-3, Haleakala and West Maui Mountains

I got into Kahului, Maui at 10pm, August 13, 2013, with a backpack and bike panniers full of gear, a boxed up touring bike, and one hell of an itinerary. I wanted to circle the island on a bicycle. My friend Mel was there to help by picking me up and letting me crash at her place in the late hour. Fun was in order. Endurance was crucial. Sleep was critical. Let’s do this.

Day 1: HALEAKALA!!!

Not wasting any time, I left early the next morning from Kihei with my bicycle and touring cargo to ride for 2 days on Haleakala, a 10,000 foot volcano on the eastern side of the island. The plan was to go across the island to Kahului, turn southeast on Haleakala Highway, eventually get to Crater Road, and climb its 6+% grade and endless switchbacks all the way to Hosmer Grove Campground at 6,800 feet. Then I planned to get up early the next morning, pedal another 3,000 feet to the summit, and catch the sunrise from the highest point in the island. The first day would consist of 35 miles, 24 of it uphill, 11 more uphill the next day, then all downhill from summit to sea level.

I rode northward to Kahului on on Mokulele Highway, and crossed a flat plain of sugarcane farms between the rugged mountains of West Maui and the larger, solitary Haleakala Volcano in the east. I turned southeast onto Haleakala Highway and watched as it made a straight climb up the mountainside for 7 miles. Not even halfway up, I already starting drying out and losing breath, eyes stinging from sweat, legs already starting to burn. The grade increased and I had made significant elevation gain within the hour.

I was surprised at how well-kept and bike friendly the road was, with a huge shoulder and bike lanes. Apparently there was a big push by the local cycling enthusiasts to make the roads safer for cycling. It made the difference, and I would easily recommend that area to other cyclists in search of good highways like I always am. I reached the upcountry town of Kula, turned uphill on Old Haleakala Highway, and continued to climb up one of the island chain’s biggest volcanoes, winding about the many turns through the upcountry.

I was a few hours in, nowhere near my goal, and had already tapped my water dry. The midday sun was baking in the upcountry, and despite having trained my ass off for this, I was getting a beating and drying out. With no idea where the next watering hole was, I pushed onward for 4 more miles, losing breath and taking breaks under every tree I could find. And I thought my Denali trip was rough.

I got to a restaurant near the exit to Crater Road. I refilled my water supply, drank three full glasses from the bar, and kept going. Crater Road is the main road that climbs up Haleakala, switching back and forth for 21 miles into Haleakala National Park, all the way to the summit. From there, you can look out over the crater to the east and hike the trails into the barren expanse of volcanic terrain. The summit is famous for its sunrise, which happens high above the cloud line. Crowds of people drive up there every morning to see it, and many outfitters shuttle cyclists there as well, where they watch the sun come up and then go flying back down. Only a few badasses ride it from the other way.

Knowing that there would be 11 switchbacks on the first section, I tried at first to keep count. I counted all of two before realizing that I was too out of my mind to keep count. The road had already steepened. Coming out of the forests at the bottom, I looked up the slopes of the volcano in horror as one switchback after another went up and up, and up and fucking up for what seemed like forever. A road sign said 3,500ft in elevation. You’ve got to be kidding me. I knew it would be hard, but didn’t expect it to be like this. At that altitude, the clear air gave way to the day’s extremes, making the high slopes blazing hot during the day and cold at night. I was in a desert of thinning air. 3,700ft and climbing, one brutal inch at a time.

I stopped on the side of the road every few hundred feet, resting my legs, trying not to drink water, occasionally telling somebody in a car that I’m alright. If you want to call not being unconscious alright, I was whatever a person’s exhaustion was at a factor exponential to fucking altitude. 4,100. I would rest, climb a few hundred feet, rest, and keep going. This went on and on and on, for hours and hours. The land below started to fade behind the humidity and glare of the mid-afternoon sun. And I was nowhere close to my goal for the day, the campground at 6,800. Every mile might as well have been 5 at the rate I was going.

I got to the straighter part of the road, hoping the grade would ease up, only to see more of the same shit. Finally, 3 miles shy of the campground, I got off, put my sandals on, and started pushing my bike up the hill. I had had enough of this. At 6,500, I reached the first forest since the beginning of Crater Road, and cooled off in the fog of the mountain’s cloud belt. The road lingered right along the forest’s tree line, passed the campground, and continued switching its way back and forth on steep elevation grades for 11 more miles all the way to the summit. In the setting sun, the mountainside turned orange and then red. Cars continued to go upward. I coasted my bike down a side road to Hosmer Grove to set up camp and call it a night.

That campground was a great reward for everything I went through that day. It sat at a small grove right at the tree line, facing the volcano’s summit. Absolutely beautiful. The sun set behind the clouds above West Maui mountains, and in no time the temperature took a dive. I wouldn’t say I was prepared for the altitude-induced exhaustion that made this trip so utterly brutal, but I had done enough winter camping to know what to bring for the cold weather. I layered up, ate dinner, and immediately fell asleep.

Free of any humidity or light pollution, the sky looked amazing from that altitude. For the first half of the night, its mountainside reflected an otherworldly glow beneath the moonlight. I came out again a few hours later after the moon had set, and could see every star in the galaxy. Having lived in the city for the last 15 years, I forgot what stars even looked like. I hadn’t seen the Milky Way that clearly since I lived on a farm as a kid.

Day 2: DESCENT!!!!

My plan was to get up a few hours before sunrise, ride 11 more miles and 3,000ft in elevation gain to the summit, and watch the sunrise. This plan got botched due to exhaustion. I overshot my limit on this one, realizing that hauling camping cargo up a mountain like that is a lot like trying to sprint across a desert. You can push yourself for a while, try to talk yourself into believing that you can make it, but eventually you’ll wind up on the ground with blood coming out of your eyes and pee that looks like a cloudy knockoff of orange flavored Gatorade.

The fact was, anytime I tried to pedal uphill, my quads would burn and tire out within minutes, I would lose my breath, and would have to stop. I was trained and prepared in every other way, but it wouldn’t matter if I wasn’t acclimated to the altitude. I think I could have waited another day and made it. If I packed more food and gave myself another nights sleep, I probably could have got to the summit. But I was on a schedule with lodging reservations in Wailuku and Hana. So I left the campground at sunrise for a 6,800ft descent to Kahului and 10 mile ride to Mel’s house in Kihei.

Immediately, I started gaining speed. A LOT of speed. With the cargo, I was accelerating at a rate that I never would have believed. I came out of the trees by the campground to the open, barren side of the volcano and looked down at towns and shorelines 6,500ft down. It was absolutely the most terrified I have ever been on a bike. Arms and feet were shaking in utter panic, and all I could do was hold on and focus, so I wouldn’t go flying over a switchback and land on the next one down. In no time, I hit 6,000ft, then 5,500, 5,000, 4,000, flying downhill around one sharp turn after another, practically burning my brake pads to tar. I rode the breaks so hard that my fingers hurt terribly whenever I let go. I would fly around a switchback, descend even further, do another, and then another, and then another. People have died trying to do this shit. And there I was, hauling ass down a huge volcano on one of the most exhilarating rides of my life.

I turned north on the highway at 3,500ft. It straightened out and the grade lessened. With bigger shoulders and straighter road, as well as a stop at a local cafe for breakfast and badly needed coffee, I was actually able to relax and enjoy the rest of the ride downhill. Finally at sea level again in Kahului, I pedaled south to Mel’s house and rested up for the afternoon and evening.

Day 3: West Maui – If You Can’t Climb It, Go Around It

I was proud of myself. Not because I hauled ass on Haleakala the last two days, but because I fixed an indexing problem on my bike’s derailleur without any help, saving me a few hours that I would have had to wait for a shop to open. My bike maintenance classes paid off.

I got moving on the southwest shoreline of West Maui on Honoapiilani Highway at sunrise. The newly paved and well maintained part of the highway wound along the cliff sides with easy gains in elevation and a big shoulder for the traveling cyclist. To the east, the sunrise broke over Haleakala, lighting up Maalea Bay in a glow of emerald and sapphire. The beaches were already crowded with surfers and tourists. The road straightened out towards the western town of Lahaina, and the island of Lanai stood some ten miles west under a canopy of clouds. To my right, steep, rugged canyons and ridges of the West Maui Mountains stood under cloud cover of their own, giving way to a dense, lush rainforest that only the most ambitious hikers try to penetrate.

Thirty miles of that highway were easy, straight riding with smooth pavement. Then all at once, shit got real. On the north side of West Maui, between Kapalua and Wailuku, there were 20 rough miles of steep climbs, scary descents, hairpin turns, and a good stretch of busted road. It was awesome overall, but I had to earn my right to enjoy it the only way knew how: on my bike. On a good note, the cloud canopy kept me cool. I climbed and descended the cliff sides for what must have been hours. I lost track of time and thought.

In the middle of the most remote, rugged section of the road lies the village of Kahakuloa, a little town with 100 people, a few roadside stands, and two churches. Right next to the town, the Kahakuloa Head stands 636 feet above the shoreline. I passed through the town and right by it on my way to higher ground. The road got even rougher, passing through more rainforests and ranches, making me think that I might well be somewhere in South America. I climbed the slopes of the mountainside for 5 miles, and then finally descended on straight, smoothly paved highway all the way to the hostel in Wailuku. I got there in the late afternoon, already too tired to do anymore sightseeing.

Last Minute Century on the Glenn Highway

Last Minute Century on the Glenn Highway

…continued from Part 1: Cycling Denali Under the Midnight Sun

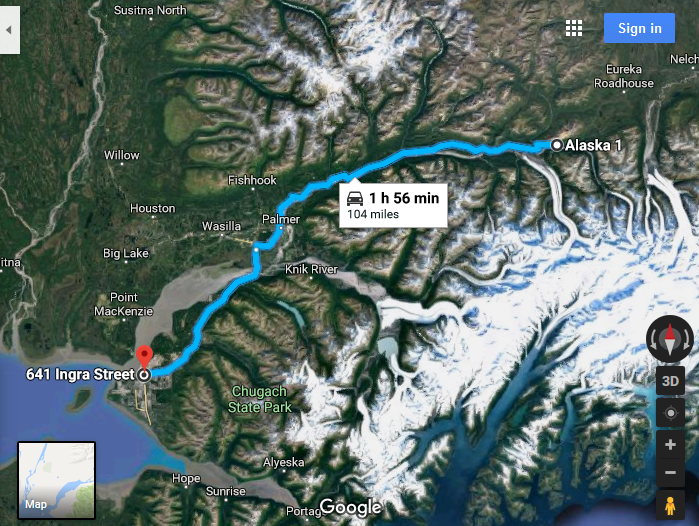

It took me a couple days to feel like a normal person again. That trip really kicked my ass. But I was satisfied that I saw Denali on a good day. It was awesome, and it was done and over with. But I still had two more bike tours planned, the next one being a 104 mile ride northeast up the Glenn Highway to the Matanuska Glacier, a large glacier on the northern end of the Chugach range. The good weather had passed and it was back to rain and erratic, unpredictable weather patterns in the mountains. So I waited for another good window, and in the meantime, got familiar with the bars in downtown Anchorage.

I spent some time emailing women online, because I was curious to know where the good bars were in town.. Since I was visiting from out of town and had some extra free time between bike tours to check out the local scene. And because I was curious to see what else they like to do around town. And then maybe one or two other random questions about their profile, and maybe if they were up for the randomness of it, meet up for a drink at a classy local establishment.

On that note, I noticed that the drinkers up there were some rowdy people. I was out with a lady one night in downtown, and a local guy next to us explained to me that a lot of the local drinkers are energy workers in Alaska’s oil industry way up on the North Slope. They go up for two weeks at a time, work for 60 hours each week, and then fly back to their homes and take the next two weeks off, which they end up spending getting shit housed at the bars.

“Up here, we only care about four things,” he said.. “Eatin, drinkin, fightin, and fuckin!”

I came back from downtown the next night and noticed that the clouds had lifted off of the Chugach Mountains. I found my window. When it’s nice, I realized, now is as good of a time as any.

I got my gear together and left the hotel at 1:00am for a 104 mile ride northeast up the Glenn Highway. Hopefully I would get there by the next afternoon, camp at the Grandview Cafe, and come back to Anchorage the following day. 208 miles, two days. With cargo. The first one being mostly uphill and overnight. I had obviously learned nothing from my previous trip.

There was plenty of light outside to get me through the early morning. The glow of dusk was endless as I rode under the twilight in what felt like a morning that would never end. The midnight sun was just below the red horizon to the north and the mountains to the east carved dark green shapes into the sky.

After 30 miles, the road turned northward and passed through the Matanuska Valley. The sun would be up in an hour. Mist hovered above the ponds and marshes. Clouds hung above the mountains to the south. To the east, Lazy Mountain rose high above the town of Palmer, where I planned to stop and get breakfast.

Palmer was the last town on the highway that I knew of to get food before going into the mountains. After that, I could have found a roadhouse every 30 miles or so, but nothing I could rely on. I sat outside McDonalds for an hour and waited for them to open before realizing that a grocery store and Starbucks in the shopping center were open already. The lady at Starbucks told me that she goes with her family up the Glenn Highway every year and camps around Mile 85, a forested area near the pass with a number of lakes and back roads.

Just east of Palmer, Lazy Mountain stands 3500 feet above the valley. The Matanuska River comes out of the range and passes around it from the east. The highway goes alongside the river for the next sixty miles upstream until passing within eyeshot of the Matanuska Glacier. That was where I meant to go.

After passing through a heavily forested, uneventful part of the highway for 10 miles, I reached the river. Up ahead, the morning sun broke out of the clouds. I stopped at a lookout where the river braids across a gravel bar a half mile wide.

This river, like many in Alaska, is glacier-fed. Over time, glaciers move along their valleys, grinding the bedrock underneath into powder, which gets carried downstream by the melt. Whatever sediment isn’t carried out to sea ends up accumulating on the riverbed, causing the rivers to braid over large gravel bars. Backpackers often attempt to ford rivers like this by scouting out the smallest braids they can find. I’m nowhere near that ambitious. Not yet.

The valley narrowed and the highway followed closely by the river until it passed by King Mountain, a large solitary mountain that looked as if it stood out over the land for many ages. I remembered seeing it online when I scoped out that highway on Google. Too bad I didn’t think to scope out the rest of the highway, or I would have been more prepared for what was coming.

To my disappointment, the highway parted ways with the river and climbed steeply along the facing ridge, gaining a lot of elevation at very little distance. So this road did have some grades, and they were ugly. Shit. I wasted no time getting started and hit the first climb for twenty straight minutes.

It turned along the slopes of the Talkeetna Mountains, giving me plenty of scares whenever I looked over the guard rails. I was inches away from one wrong move, which could send me tumbling over rock slides for hundreds of feet. I turned back and saw a great view of King Mountain rising high above the river and forest to the west.

Out ahead, the highway continued to climb, occasionally giving way to a downhill coast to a stream, and then winding even further upward. I did nothing but climb for the next hour, hoping that I would come around a turn and see the road level out, only to see it go further upward.

Somewhere in the middle of this, I passed a lady named Renee, who was on a tour from Anchorage to Los Angeles. It was her second day in. She spent the last night in Palmer, planned to get over the range, and continue towards Glennallen in the east. After talking I bit, I passed by, pushing hard into the next mountain grade. She had more cargo and was pacing slowly for the long term, and obviously intended on saving her strength. Instead of say, leaving in the middle of the night for two centuries back to back.

At this point, the top of the pass was five miles ahead. To my right, the mountain slopes curved down to the edge of a gorge, where at the bottom, the Matanuska was raging in the late morning sun. Lakes were everywhere along the slopes, drawing local people far and wide to come out in trucks, RVs, and fishing gear.

I finally made it to the top of the pass around noon, and the valley opened up ahead. To the south, the Matanuska Glacier reached far across the valley, carrying ice and rock from the high places of the Chugach range, where it turned upward for another twenty miles. Headwaters braided out from the glacier, forming the river, and carving into the ravine downstream.

Lion’s Head, a small, horn shaped mountain, stood on the north end of the valley. It was the remains of an ancient volcano that had been scraped away by glaciers long ago. After millions of years of friction, it was all that remained of a prehistoric mountain in the alpine country. And still, this place was as wild as ever.

The fatigue finally caught up with me at mile 100. I crested the high end of the pass, and hoped to get 9 miles of mostly downhill, where I would set up camp at the cafe, get some coffee and red meat, take a long nap in my tent, relax and enjoy the rest of the afternoon.. oh shit. I came around a turn and looked in horror as the road went downhill at a 7% grade for almost a mile to the bottom of a canyon, then crossed a bridge and went back up the other side at 8%.

Already exhausted from riding all night, and with only four miles to the campground, shelter, and hot food, I had to haul my cargo up a fucking mile of hard uphill. Dammit.

Bitterly, I coasted down to Caribou Creek and started a long climb up the other side. A climb like this in the early morning is one thing, but I had already been on the road twelve hours. I fought my way up the other side, inch by inch, swearing and taking breaks every few minutes. It made no difference.

The road finally leveled out, and I descended to the cafe where I got the best Philly Cheesesteak of my life. I’m pretty sure my chest hair increased by 8% that day.

The Grand View Cafe is on mile 109 of the highway, on the eastern slopes of the range. It has a restaurant, RV park, tent sites, families, dogs, campfires, and short hiking trails out to the river. When I got there, I set up my tent, locked my bike, ate a rewarding lunch, and took a nap until the late afternoon.

I got back out and saw Renee setting up camp at the site next to mine. She planned to keep going east to the town of Glennallen the next day, another 75 miles of mostly gradual descent from the range, then make her way out of the state and into Canada after that. For this trip, I would be turning the opposite way, riding 104 miles back to my hotel in Anchorage.

Next time I want to keep going east. The highway descends out of the mountains and levels gradually into a large plain of lakes, tundra, and spruce forests before reaching Glennallen, the Copper River, and the edge of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. From there, you can see the St. Elias Mountains, some of whom soar higher than 15,000 feet. The Copper River flows along the edge of the plain, and is famous for its salmon, who migrate upstream to their spawning grounds every summer by the millions. People and bears alike wait for them in the river, easily catching more than they can ever eat. I would love nothing more than to get out there, wait by the water, and eat one right out of the river like a fucking caveman.

A family in an RV saw me with my bike and gear, covered in a night’s worth of dirt and sweat, and wanted to know where I was headed. Then they offered me some of their campfire hot dogs and homemade wheat beer. I’m never one to turn away good road magic, and took them up on it.

Isolated rainclouds came in from the east and ran me back into my tent, where I slept like a rock.

My phone alarm went off early the next morning and I didn’t want to get up. I’m pretty hit or miss when it comes to camping. Either I’m asleep peacefully, or I’m tossing and turning, waking up every 45 minutes. Thanks to the workout I got the day before, and the light drizzle of rain on the tent ceiling, I had a calm, uninterrupted sleep all night.

I packed up, got a quick breakfast, and turned west on the Glenn Highway, dreading every second that I would have to climb the far end of the 7% grade at Caribou Creek. It was the same distance as the day before, just a notch lower in difficulty. Instead of climbing 8 feet, I would only climb 7 for every 100 in distance.

I descended down the facing grade, crossed the bridge, and got moving at a good pace as soon as it got to 7%. Ten minutes later, I got to the top, surprised at how much better I felt. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it was easy, but it was, I would say after a good night’s rest, doable. It turned towards a short descent, another steep climb, and then mostly downhill for a while.

Every awful climb I endured the day before was in my favor now, and my cargo weight made me go even faster. I was on the side away from the guard rails, my confidence was at an all-time high, and I had no problem shifting into high gears, flying down the grades, following the Matanuska for 60 awesome miles all the way out to Palmer.

I got there in the early afternoon, coasted down a big hill, and made the mistake of getting dinner at McDonalds. A man standing in line recognized me from the campground, reminding me of how small the world is in a big state like Alaska.

I was just about at sea level when I left Palmer, turning south at the junction towards Anchorage. It might as well have been uphill with the headwind I was getting. That, and to the traveling cyclist, a McDonalds combo is the equivalent of adding ten pounds of rocks to your cargo. The last 40 miles back were uneventful, and I had to deal with the added punishment of two centuries worth of riding and a full stomach’s worth of bricks to burn off over the next few hours.

I got to my hotel at 6:00 that evening and fell asleep without bothering to eat or take a shower.

I had two bike tours behind me now. Both of them kicked ass. Both of them were brutal. And both of them were unbelievably rewarding. Would my last ride on the Seward Highway bring its share of challenges and blow my mind like the first two did? Probably. Would I have a bigger, fuller beard after it’s all said and done? Absolutely.

Maui Day 6-10: Upcountry and Kihei

Maui Day 6-10: Upcountry and Kihei

…continued from Day 4-5: The Road to Hana

Day 6: Hey that’s Oprah’s road, let’s turn there… wait a minute

It was the last day of my tour and it wouldn’t be easy. There was a 3,000ft climb up ahead to the same part of the upcountry where I had been on my first day. But the route from the southeast part of the island is much more challenging. Much of the road is beat up and poorly maintained, some if it is gravel, and it still winds along treacherous cliff sides. It goes up the side of the mountain on a mostly barren, volcanic section of the island that is for all intents and purposes a desert. And it would be like that for 25 miles. It was the toughest part of the coastal highway system by FAR. I knew I needed to leave early to get through it before the sun rose to an unforgiving angle on that arid side of the mountain.

But hey, who wants to miss a good sunrise with their friends in a place like this? Not this dude. Four of us sat on a rocky outcropping along the shores of Kipahulu as the sun came up from behind the sea and set the sky on fire.

Twenty minutes later, I was off. The pavement gave way to dirt, I crested some hard passes, and equally as gorgeous cliffside vistas. Not a single beach I saw on my whole trip could hold a candle to that of the lost shores of Lone Keawe, whose rocky beach spread out between two huge cliffs. The dirt road descended to the edge of the beach, passed the facing cliff, and ascended into more madness. What a remarkable hidden gem on an otherwise blackened side of the mountain.

After a few miles, I got out of the cliffs and hit pavement again to my relief, only to discover that it was even worse. This section of the highway was paved a long time ago and hasn’t been repaved since. Potholes have just been patched as seen. For a long fucking time. So at this point, the entire road was covered in patches. It’s saying a lot to point out that this was actually worse to ride on than gravel. I actually had to go slower downhill not to lose control on all the shitty, bumpy non-road. This went on for 8 miles. 8 miles in the mid-morning, right when the sun was waiting to dry me out like a dead animal.

All of a sudden, I crossed a bridge and hit smooth pavement. That’s more like it. From there, the newly paved stretch went uphill for 10 miles before passing around the side of the volcano and into more forgiving, forested land. Sea level to 1,800 feet with no time to waste. The sun was out now in full force, and as badly as I needed water, I knew I had to ration what I had left. I finally crested the high ridge and turned northward to Kula, reaching cooler air and the shade of trees. With a half a bottle to spare, I made it to the first watering hole in the late morning, a ranch cafe in Keokea. All my training paid off.

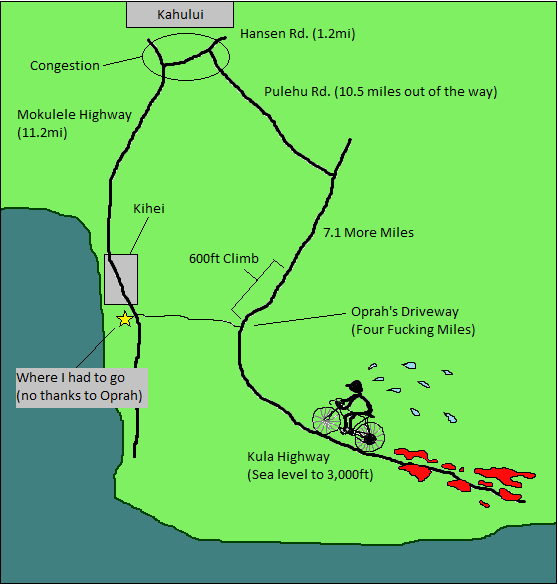

After getting lunch and refilling my water supply, I continued my climb along Kula Highway. I bitterly passed the driveway to Oprah’s ranch. She bought land in Upcountry Maui a few years ago in a section between the Kula Highway and Kihei, and paved a private road between the two. To date, it is the only one of its kind in that area. The state has yet to pave a badly needed road between the two parts of the island, something the locals have wanted for years. For me, it would have meant that I could have coasted down to Mel’s house in 20 minutes. But since that driveway was closed to the public, I had to take the alternate route:

(7.1 + 10.5 + 1.2 + 11.2) – 4 = 26 reasons not to listen to anything Oprah has to say about resource conservation. Everybody on the island has to use more gas because of this, and the lack of a public road in that area also contributes to more traffic in Kahului. To make it even more obscene, Kihei and Wailea are perfectly visible from the uphill side of her driveway. I motion that Hawaii exercise its power of eminent domain. Open that road up to the locals, and leave Oprah a tidy sum. Hell, even if she did something shitty like charge a toll, I would have taken it. I was just exhausted and wanted to get back to Mel’s house so I could take a well earned nap. Instead, I turned north and gained another 600ft on the mountainside and descended 3000ft down Pulehu Road to Kahului.

I made a quick stop at a coffeehouse to flirt with a barista who I met on my way out to Hana a couple days earlier. She wasn’t there, so I came back to Mel’s in Kihei, finishing the tour at 2:30 in the afternoon. A big meal and a bike coma were in order. I passed out for 3 hours in a hard, deep sleep that I only get after long bike rides. They’re dreamless, and a couple notches under being knocked out. Whenever I do wake up, it takes me at least two hours to feel alert and functional again. I think I even get kind of high from it. They are amazing.

Day 7-10: Kihei – Turtle Watching

I did it. My 6 day bicycling expedition was over with, and now I could relax. I had four days to waste, which was fine by me.

I started by taking a snorkeling trip, thanks to Mel’s friend Delphine, who helped me get a half off deal through her company, Pride of Maui. She picked me up early in the morning on her way to Maalaea Harbor, where we got on a boat and left with a hundred other people for Molokini island. It is a small, crescent shaped island a few miles southwest of Wailea with a huge reef around it, and crystal clear blue water where you can see the ocean floor some fifty feet down. Because of this, Molokini is a popular destination for snorkeling and scuba diving. I was excited to get out with my camera and get some footage of the marine life.

After about an hour of swimming in the reef, I got back on the boat and we went to Turtle Town, another reef nearby with a healthy number of green sea turtles. A good hundred of us were out there looking for them and didn’t see anything for a good half hour. Finally, we spotted one resting on the sea floor. They can hold their breath for hours, so there was no telling how long that dude was down there, or how long he planned to be. Out of nowhere, another one swam ahead thirty feet to my right. I was one of the first people to take off after it. As it turns out, my camera was pointed too high and I only got a half second of it. Oh well, it looked pretty sweet.

I spent the rest of the time on the boat, eating chicken off the grill, drinking margaritas, and listening to the announcer describe the landmarks and scenery around the bay. He was in his fifties, and looked and talked like he used to host a game show. Delphine was on a break, and came over. She pointed out Oprah’s driveway, reminding me of all the fun I had yesterday in the upcountry.

I knew all about that road. It was why I had to ride for three extra hours in the heat at the end of my tour. There it was, clearly visible from the bay, winding its way up the mountainside like a fucking ribbon through time. And it’s not even her primary home, which is in California. I guess that’s what you can expect from the same person who gave us Dr. Phil. Screw her.

Early the next morning, I got up early, walked a block down the street, rented a paddleboard, walked to the beach, and got in. Thanks to Mel’s location, it really was that easy. She’s got a hard life, I have to say. Her friends worked at Maui Wave Riders, the surfing outfitter right by her house. Thanks to the connection, I got a good deal on the rental.

I had never done stand-up paddling before, but was well aware of how popular it was getting in the world of water sports. I figured I would give it a try. I paddled on my knees past the breaks to the calmer water, made a few attempts to stand on the board, kept falling off, and finally got it. It was a bit more relaxing than other water sports, which is why I didn’t enjoy it as much. After an hour or so, I got bored. I guess I just like to take out aggression, either by surfing or paddling down a wild river.

Out on the reef just past the breaks, three sea turtles floated on the surface, bobbing their heads up out of the water. I realized that they really were everywhere out here. Thanks to a good conservation program, they flourish on the reefs around Hawaii, and are common enough to be a normal phenomena to the locals. With a lifespan of 60 to 70 years, they can outlive many of us. I wonder what kind of wisdom a turtle of 70 years would have for we younger mortals. What goes on in the minds of these graceful creatures? They truly are badasses of the tropical sea.

The next morning, I went back. I wanted to learn how to surf. So I signed up for the first class of the day. It was just me and four sisters, and all of them were 8 years old. The instructor started by having us practice jumping on soft top boards, explained how and where to position our feet, and how to balance. Then we picked up our boards and went to the beach.

This would be a piece of cake, I thought. Especially since I’m competing with 8 year old kids. The awesome bearded mountain man that I am. I can kick their butts at this. I am a highly fit, well balanced, rugged outdoorsman, and they are 8. I’m going to win at surfing. I’m going to ride every good wave into the shore, and I’m going to rule at it. And they probably won’t.

Wrong, wrong, and wrong. I have not been that wrong about anything in years. I wiped out time and time again, sending the board in the air nearly every time I tried to stand, while every last one of those girls caught waves and rode them to shore, over and over and over. The instructor kept telling me to paddle, look ahead, get my feet up, get them in the right place, whatever, and I kept wiping out. Finally after a couple hours, I figured out when to catch the breaks and get my feet up. I started catching the waves. It was shaky, but I was getting it together. I was exhausted and got out.

I needed a break from all of this. I was having a blast, but needed to relax somewhere quiet with air conditioning and zone out on my computer. I got cleaned up and went down the street to a Starbucks. It was my first chance to download the latest issue of the Walking Dead comics, since there weren’t any comic book stores on the island that sold it. I keep telling fans of the show to read the graphic novels, and that they really do outdo the show in awesome, desperate, brutal survival horror. That is, until lately, the shitstorm of things going on at the prison is finally getting to the same caliber. That, and Andrea is dead, so that helps. In the comics, Rick was in the middle of a standoff with Negan, a new villain who makes the Governor look like a youth pastor.

I didn’t get the chance to see Breaking Bad that Sunday since I was in Hana, so I bought some headphones and downloaded that next. A few episodes into the second half of Season 5, Walt’s empire, and his family along with it, were on the verge of a meltdown. In a promo commentary, the season was described by Cranston as a “Roller coaster ride to hell”, and this was the point where the roller coaster was inches away from a freefall. Nothing good could come of this, and as expected, I was right. Everything, and I mean everything, went to shit after that final curve of the story arc.

It turns out a good nights sleep was all I needed to let the muscle memory sink in. I rented another surfboard the next morning and hit the waves bright and early, nailing the very first one. Then I got the one after it, and the next one after that. I rode one wave after another into the shore for hours. At one point, a manta ray of three feet zoomed behind me and out towards the reef. Certainly as graceful as I remembered from TV, but I had no idea they moved that fast. An instructor told me he spotted a family of four of them close to shore earlier that morning.

After a couple hours, I was ready to come back to shore and get food. That, and the Cove was pretty crowded with surf classes. It wasn’t as much fun when I had to worry about dodging other beginners. I rode one really great wave all the way to the exit ramp, decided to end on a good note, and got out.

Later that night, a few of us went to Fourth Fridays, a town party in Kihei. Every Friday, one of four towns in Maui has a big street festival, and Kihei happened to have theirs on the same night that I planned to leave. Perfect. There was live music, art galleries, vendors, a food truck row, alcohol, and crowded bars. All right down my alley. We walked around, drank beer, ate good food, hung out. For the last time on the trip, I saw Haleakala turn red in the setting sun, feeling a bit sad to leave, but ready all the same. I never did get to that summit, so I guess that means that the volcano and I have some unfinished business.

Several hours and beers later, I said goodbye to Mel and her entourage of good people, and boarded an overnight plane to San Diego.

Mel asked me at one point if I thought I would come back to Maui again. I would like to, but I honestly have no idea when. Maui was just one place on a huge list of places I want to travel, and that list has already gotten bigger since I’ve been home. There’s Haleakala’s summit, which is doable with a better bike and a better plan. I know I can do it with a good carbon fiber bike and a death wish. That, and I would like to get certified for diving. The snorkeling was fun, but I think I would enjoy being able to stay underwater for longer, immersed in sea life and coral.

The fact is, all this shit that I’ve been describing to you is only the surface, and there is a whole myriad of things to do on that island. Pretty much every spot I rode my bike past has something about it worth checking out. But I’m glad to say it’s another place I can check off in my lifelong goal to travel the world on a bicycle. And I suppose it is halfway between me and New Zealand, so there’s that.

Maui – Day 4-5: The Road to Hana

Maui – Day 4-5: The Road to Hana

…continued from Day 1-3: Haleakala and West Maui Mountains

Day 4: The Badassery is in the Journey

Flat tire. Fuck. There goes my early start.

I went ahead and switched it out, but realized that I needed some extra tubes for the rest of my trips in case it happens again out on the Hana Highway. The nearest bike shop in Kahului didn’t open until 9. I guess I had some time to kill. I walked around Wailuku in the early morning as the town was still waking up. I checked out of the hostel and coasted down to Crater Cycles in Kahului. Good experience. The owner switched out the back tire for a Gatorskin, which held up for the rest of the tour. He even fixed a truing problem on the wheel free of charge. I needed the reassurance that my bike would hold up on the Hana Highway’s own set of surprises. Riding with confidence in your bike’s ability to not break down in the middle of nowhere is pretty damn important.

I set out eastward on the Road to Hana at a good, hard pace, easily passing the town of Paia. It had a busy downtown strip of old buildings and shops, and was already drawing a lot of traffic. As before, the straight road gave way to turns around cliff sides and rugged coastal rainforest. Famous for its diverse landscape, winding roads, sheer drop-offs, waterfalls, and numerous interesting places to stop every few miles, the Hana Highway is often noted by travel enthusiasts as one of the Best Highways in America. I pretty much agreed, although it did have its share of challenges. Like West Maui, the road was pretty wild.

But it would be worth it to see Hana, a small east coast town of 1,235 people. It is popular for its beaches, hiking trails, lava caves, and a general store of more than 100 years, and draws many people looking for a remote Hawaiian experience. Having the charm of a small town, Hana remains largely unchanged by Maui’s commercial developments further west, which is how they like it.

This kind of country was what drew me here instead of one the other islands. When I scoped out Oahu, it seemed pretty overrun with tourists and commercialism, all at the expense of a person’s solitude. And then some of the other islands didn’t appear to have as much diversity as Maui, whose rainforests and barren, volcanic landscapes offer a change of scenery around every turn. Thirty miles into the Road to Hana, I was certain I made the right decision to come here. It was fucking beautiful.

I went up and down the rugged shoreline for hours before reaching Puokohamoa Falls, where tourists were surprised to see me out there hitting all those tough hills. I told them it was a piece of cake, and started another big climb that went away from the shore and inland for 6 miles. It wasn’t really a piece of cake, it was actually getting a beating, a few feet a time up the side of the same volcano that wiped me out a few days before. And then all at once, I crested the highest ridge, turned back to the sea, and coasted down to Hana for 12 awesome miles straight. On the newly paved road, I felt like I was floating an inch above the ground. Hana may be a gorgeous place, but the badassery really is in the journey.

Just north of the town, I turned off the highway towards Waiʻanapanapa State Park, found the campground, and set up my tent in the mid-afternoon, making pretty good time.

Waiʻanapanapa is an especially rugged, volcanic section of the coastline just north of town. With a great coastal trail, black sand beach, water caves, blow holes, and a spectacular sunrise every morning, there is little not to like. A person could spend days at this place and never get bored. After setting up camp, I spent the next hour walking up and down the trails around the ashen volcanic cliff sides, watching treacherous waves crash against the walls. Apparently, the water here was full of undertows and hazardous currents, waiting for its chance to drag an unsuspecting person out to sea.

That night, I walked out around 2am and looked out at the ocean. Even in that hour, there was a glow of blue about the sea, as waves continued to crash violently against black, volcanic cliffs. One of the hardest days of the tour was behind me now, but it wasn’t over yet. I was about to face an even tougher road ahead.

Day 5: Kipahulu – Two Miles of Eye Candy

An awesome, rewarding sunrise set the mood for the next day. I packed up my gear as the golden sun brightened on the water, and left for the Hana Lava Tube. On a piece of land a couple miles north of the park, the cavern, originally named Ka’ Eleku, was carved by lava flow coming down from the high slopes of Haleakala. Its surface crusted over, forming the cavern’s ceiling and an underground conduit that at one time continued to channel lava until whenever the eruption ended. For $12, visitors can explore the tunnel, making it one of Hana’s popular tourist attractions. I planned to meet my friends there before heading out. They were an hour late.

To kill time, I went to a roadside stand nearby and got the best banana bread I have ever eaten, followed by an equally as delicious fruit smoothie with homegrown bananas, mangoes, and pineapple. I was full in no time. The old lady, a type who they refer to as an “auntie” did what aunties like to do and fatten up we younguns. Full or not, she brought me another smoothie. And of course I had to drink it. What choice did I have?

Feeling as bloated as a dead pig, I went back to the main desk at Hana Lava Tube and found Mel, Kim, and Dave. We got flashlights and explored the tunnel for a good hour. The ceilings had lava stalactites that resembled hershey kisses, although I thought they looked like shit. It was cool, don’t get me wrong, but it was the first time I’ve witnessed what turds look like on a cavern ceiling. Besides the crap-covered walls, there were signs describing the different types of lava formations about the cave, a side tunnel caused by back flow, and a door to an abandoned fall out shelter from the cold war era. Cool place.

We came back out, explored the botanical garden maze just outside of the entrance, and then they took off for the campground at Kipahulu, another 12 miles down the highway. I got on my bike and told them I’d see them in a couple hours.

The highway between Hana and Kipahulu was more of the same thing. Winding cliffside turns, an old beat up road, and no shoulder. To add to the fun, a lot of tourists were out driving. I would descend a huge cliff to a bridge and waterfall, with five cars ahead of me and four behind. Sometimes I would stop and let six or more vehicles pass. When I got to the bottom of one of the grades, I passed one of my neighbors from the campground. I’m never one to turn away good road magic, especially beer, so anybody who offers me a drink is a friend of mine. Last night he gave me a bottle of a good craft brew, which always tastes better after a hard day of riding.

Tough road, but only for 12 miles. I coasted into the campground at Kipahulu and found my friends. They went out on the trail while I set up camp and had a look around. The whole area was buzzing with tourists, and with good reason.

Kipahulu is an especially diverse part of Haleakala National Park. A large stream comes down the volcano and pours over two large waterfalls, passes through bamboo forests, and ends at the Pools at O’heo Gulch near the sea. The Pipiwai Trail follows the stream uphill past the waterfalls and forests for two miles before reaching Waimoku Falls, a stunning 400ft drop of water over a vertical face of volcanic rock and moss. I spent a good hour hiking up there. The bamboo forests had a dark canopy above them, though beautiful, made me what kind of evil lurks in those trees. Just beneath the canopy, wind blew the chutes back and forth, creating a hollow knocking sound that I can distinctly remember to this day.

After taking a good look at the waterfalls, I descended back down the canyon for an hour towards my campsite, looking forward to the luxuries of car camping. As I walked back, I noticed the “big island” of Hawaii to the east, and Mauna Kea rising high above the ocean. At a summit of 13,803 feet, Mauna Kea is the largest volcano in Hawaii. At that altitude, it rises high above the cloud line and retains low humidity, making it an ideal base for astronomical research. A section of its summit is zoned for research facilities owned by various countries, and there are thirteen telescopes in operation, gathering information and data from space.

I descended the hill to the campground as the setting sun reflected its light from one of the telescopes. From 60 miles away, it looked like a star had just come up over the summit. This was by far the most remarkable thing I saw on my trip.

Downpour on the Kenai Peninsula

Downpour on the Kenai Peninsula

…continued from Part 2: Last Minute Century on Alaska’s Glenn Highway

I had just over a week left in Anchorage and was starting to get tired of the place. I had seen everything that was interesting about the city, and was at the point where it was time to either stay and make new friends, or move on. Nonetheless, I had one bike trip left that I wanted to do before leaving: A two day tour up the Kenai Peninsula from Seward to Anchorage.

From Anchorage, the Seward Highway goes south for 128 miles, passing southeast along the shores of the Turnagain Arm for the first half of the drive, and then going south through the Kenai Mountains for the other half, and stopping in the port town of Seward. The Alaska Railroad has a line that goes straight there from Anchorage early in the mornings. My plan was to take my bike down there on the train and spend the next two days cycling back up the highway.

The problem was that almost every single day had rain in the forecast, and I really didn’t feel like riding on cold, wet roads. That, and I was hoping for a good sunny break like I got up in Denali. As I’ve said already, Alaska is beautiful regardless, but only during clear sunny weather do you get to enjoy the scenery to its fullest.

Unfortunately, in the summer, coastal Alaska tends to be cloudy and rainy just about all the time. So I waited a few days, spent some time on short day rides in the forest parks around Anchorage, got work done in my hotel room, screwed around and wasted time.

I went up to the trailhead of Flattop Mountain one afternoon on my bike. It stands right at the edge of the Chugach Mountains east of town, and is a popular day hike spot for the locals. What I didn’t realize was how steep the climb was to get up there, and was actually pretty well beat up by the time I reached the parking lot by the trailhead. The mountain was covered in clouds, so climbing to the summit just to look at fog seemed kind of pointless. I got a few pictures of the valleys around and went back down to Anchorage.

I finally got my train ticket to Seward a day or two later. There was a 30% chance of rain in the forecast, but with three days to spare before flying home, it was now or never. I rode to the station early the next morning, checked in my bike, and boarded the train.

To say the least, the Alaska Railroad was impressive enough for me to recommend to any visitor. Many of the train cars had upper decks with glass dome ceilings, allowing tourists to sit and view one breathtaking panorama after another. As soon as the train started, people scurried to the upper decks to get good seats for the ride southeast. Knowing that I was going to see all the same places the next day on my bike anyway, I didn’t bother to join.

We went southeast along the Turnagain Arm, a large inlet that flows between the Kenai Peninsula and the Chugach Range. The Kenai Mountains and the remote town of Hope, Alaska stood five miles to the south across the water. Five miles as the eagle flies, and ninety if you want to drive there. Up ahead, the morning sun broke out of the clouds, casting gold onto the water. The announcer pointed out some dall sheep high on a ridge to the left.

I got breakfast in the dining car and slept for an hour. I woke up and noticed that we were already somewhere in the Kenai Range, parting ways with the Seward Highway and climbing up over the next mountain pass to the east. The forests in this part of the state were darker, denser, more lush and enchanting, and were part of a temperate rainforest that spans from that area to the southeast and down Alaska’s panhandle. In this climate, conifers can grow for longer seasons than those of the boreal forests throughout Alaska’s interior. I looked out at the land, and clouds hung low over the valleys, reminding me of the woodlands of the Pacific Northwest. It was a dreary, charming landscape.

We went along a cliff, through a tunnel, past a waterfall, and stopped on the announcer’s word along the facing ridge of Spencer Glacier, whose blue ice had carved a steep, mile wide valley into the earth.

The train rejoined the highway, where I planned to ride that day, and made its final descent through the dense forests to the depot in Seward.

Seward is a beautiful place. A small fishing town along the rugged coastline of the Kenai Peninsula, it sits on the western side of Resurrection Bay, which flows south between mountains and islands for twelve miles before reaching the open ocean. To the east and west, there is nothing for hundreds of miles but a rugged glacial coastline and an occasional fishing town or village. Directly west, the Kenai Fjords National Park draws tourists and backpackers, many of whom come down on the train from the north and ride commercial cruises within eye shot of the glaciers and sea life. The more ambitious people traverse the fjords with kayaks or packrafts. And if you take a boat and fishing gear out to sea, you can catch more salmon and halibut than you will ever know what to do with.

To say the least, I regret my decision not to stay there longer. I made time for a quick stop at the Resurrect Art Coffee House, a cute little place in downtown, chatted with the barista, fueled up on some pastries, and got started on a 68 mile ride north through the Kenai Mountains. I passed the marina on my way out, catching a good scent of a recent catch from a town fishery. Fuck, I have to come back here.

I was 30 miles into the mountains. They seemed to close in around me. And yet, every uphill climb I did on that highway was a breeze. Nothing like the grades I fought on the Glenn Highway, or the ones at Denali that made me almost give up and turn back. I crested one easy hill after another, following rivers through the steep, narrow valleys and cooling off under an occasional drizzle.

Halfway through the day, I stopped at Summit Lake Lodge and got a hot meal. The owner told me that it was the highest point in the range, and that everything afterward was at a downhill descent all the way to Turnagain Arm and the edge of the ocean.

I stopped an hour later at a ravine to get some pictures, and noticed a large bird gliding a hundred feet right above my head. When I looked again, I realized it had a white head. Holy shit, that’s an eagle! It turned and flew out over the gorge, catching an air current and flying upward in long, slow circles until I could barely see it anymore. I got back on my bike and made for Turnagain Pass, twenty odd miles ahead, and planned to camp that night.

Each of my three bike trips in Alaska had their set of challenges. In Denali, it was the 10 mile climb up Sable Pass with heavy cargo (especially that fucking bear canister), the clouds of mosquitoes, and sleep deprivation induced delirium. On the Glenn Highway, it was the fact that I had to climb an 8% grade after biking for more than 100 miles overnight. On this trip, it was the wall of rain that hit me in the face when I came around the turn at the bottom of Turnagain Pass.

In no time at all, I was drenched. I hadn’t done my homework and bought waterproof gear or eye protection. As the downpour hit me in the eyes, I picked up the speed to get to my camping spot, where I could hopefully set up a shelter and dry off.

I reached the rest stop on the highway, found the large hill to the west, and looked for an easy way to get to the far side and set up my tent. I needed to hurry the hell up, it was getting cold and the rain wasn’t stopping. I found a game trail that led out to the side of the hill, crossed a creek, pushed through a bramble of willows, found a level spot away from eye shot of the highway, set up my tent, and got my ass inside.

It rained all night. I don’t know if it was condensation building up on the tent walls, or a leak somewhere, or both, but water kept accumulating on the corners. It was a cheap $40 Wal-Mart tent that just big enough for a cub scout, and as far as I am concerned, was a piece of shit. I spent two hours mopping water from the tent floor before I finally decided to just sleep through it. If it wakes me up, so be it.

My sleeping bag ended up saving my ass. I woke up and noticed that it had gotten lighter outside. It was 6am. I had slept for four hours. Good enough.

The downpour stopped. Outside, the landscape lightened and a break of sun came out on one of the mountains. It wouldn’t stay that way for long. The rain was hitting the tent in rounds all night, about one every 30 minutes, so I knew I had to get moving.

I packed up, hiked back to the rest stop, and got my gear together in one of the outhouses. I got my tent out and threw that piece of shit in the trash, drank a reserve bottle of water, and had a bag of beef jerky for breakfast, freeing a good ten pounds from my cargo.

As soon as I got back on the road, another downpour hit me head on. In that early hour, I could feel the cold right away in my fingers and toes, which started to go numb after twenty minutes. I supposed it’s to be expected if you’re using fingerless gloves and cotton socks, yet another backpacking lesson learned the hard way.

I came down the pass to the edge of the inlet shoreline, an absolutely stunning vista of panoramic scenery, with tall, breathtaking mountains to the north, south, and east, but I was too groggy, hungry, cold, and pissed off at the weather to give a shit. The highway turned southeast, crossed the rivers that emptied into the Turnagain Arm, and then went northeast along the shore for 40 miles all the way back to Anchorage. Fog hovered around the tops of the mountains, and the valleys between them were dark and grey, taking in one downpour after another. More cold rain hit me as I traveled east. When is this shit going to stop???

I was 20 miles from Girdwood, a ski resort town along the highway. I planned to find a roadhouse or diner there and get some much needed shelter, hot food, and most importantly, coffee. When I arrived, I found a shopping center right by the highway with a family restaurant.

I tried to lock my bike and the key to my U-lock stopped half way. Fuck. Weather and dirt must have worn it down, rendering the thing useless. Could be worse; at least it didn’t happen after locking it. Then I would have had to bust it off with a car jack or blowtorch, and maybe convince a few people that I’m not trying to steal my own bike.

I parked it next to the front door of a coffeehouse and went inside for some coffee and pastries. I got in line behind a group of cute hippie girls, one of whom had done some touring herself. Apparently, it was supposed to be nice that day and a festival was going on in the town. They told me I should come along. If I hadn’t already made plans in Anchorage that night, I would have taken them up on it.

I rode a few streets into the town and found the trailhead to the Bird to Gird Trail, an awesome bike path that goes along the ridges above the highway for 13 miles. Up ahead, clouds broke up where the fjord met the ocean, giving way to a bright blue sky.

A warm, dry, powerful tailwind hit me from behind, sunlight broke on the bigger mountains, and just ahead, another eagle flew above a spruce forest along the slopes. They are abundant in the boreal country, especially along the mountainous shorelines, where perch sites are plentiful and views of the water are far and wide.

The trail climbed uphill a few hundred feet and then descended back to the shore, ending at Bird Point, a bird sanctuary where you can walk up to a platform and watch eagles in their habitat. I didn’t see any, and figured they were out catching their food from the water.

I got back on the highway, the sun was finally out, and an even more powerful tailwind pushed me along. I barely even had to pedal. It was great severance pay for all the shit that I had endured the night before. Alaska’s climate, unpredictable though it may be, can sometimes work in your favor. Cyclists passed me going the other way, fighting the same wind current that I was enjoying. Watching them do that was an added bonus.

I got to Anchorage an hour later, and saw yet another eagle gliding into the air currents high above the marshy shoreline. My hotel was near downtown, another 7 miles north through the city. I just about coasted the rest of the way. I did it. I got to Alaska, I saw more unbelievable things that I could ever remember, and I toured what are without a doubt some of the best highways in America. What I saw and did in this countryside would stay with me forever.

I had met a lady named Ana the week before, who was living in Anchorage for the summer and working at a hot dog stand in downtown. I thought it would be funny to give her a surprise visit. So my trip ended as I sat next to her hot dog stand at one of the city parks, eating reindeer sausage and restoring my body of same badly depleted calories and protein.

Two days later, I was on an overnight flight back to Chicago.

It has been a year and a half since I made that trip. And I’ll be honest, there is not a single day that goes by that I don’t think about that wilderness. Even now, I scribble out bike routes, backpacking ideas, rafting trips, more places to explore in Denali, the eastern ranges, the rest of the Kenai Peninsula, it’s just endless. I want more than anything to get back out there again. It brings solitude and adventure like I have yet to find anywhere in the lower 48. Anywhere. There isn’t enough time in a whole summer for me to see everything that Alaska has to offer. But I’ll try. I’ll try to be satisfied. And I’ll be back with a new and better itinerary.

Cycling Denali Under the Midnight Sun

Cycling Denali Under the Midnight Sun

Alaska was a new world for me that summer. I spent months planning a three week trip to Anchorage at the end of June, laying the ground work for what would become three unbelievable bicycle tours across the state, each with its own challenges and rewards. Each tour was unique, and each was like nothing I expected.

I found a hotel near downtown Anchorage with a good weekly rate, booked three weeks from late June to early July 2012, boxed up my bike, and spent a long and shitty flight on a plane that got to the Anchorage Airport at 2 in the morning. It was days away from the summer solstice. A glow of twilight lay over the city, and the air was warm. Clouds hovered above the Chugach Mountains to the east. I went to sleep at the hotel with an odd case of jet lag, thanks to the 22 hours of daylight that Alaska gets in the summer. But I made it. And the next three weeks would entail some of the best tours I have ever done.

Denali was the first place I wanted to go. I have loved mountains ever since I was a kid, and this was my chance to see the tallest one in North America. At 20320 feet, Denali rises three times as high as most of the mountains around it, making it visible for hundreds of miles across the state. I wanted more than anything to see it in the clear. And not just to see it, but to earn the right to see it from a bicycle. I had to get my bike out there, get into the park, and be in good sight of it on a nice day. Everything else about my trip could be a complete failure, and I would still leave Alaska feeling satisfied if Denali decided to appear on my ride.

According to the locals, it shows itself one in every three days. The rest of the time it is covered in clouds. It’s so big that it generates its own weather system, meaning that it can be a great day everywhere else on the range and you’ll still find blizzards high up on its ridges, and shrouds of cloud cover concealing its beauty. My challenge was making sure that I got out to the park when it decided to show itself. For the first few days, this turned out to be a waiting game.

The weather forecast looked pretty hit or miss. So I got comfortable and waited. My whole trip hinged on this, and I could wait as long as I had to.

Later that week I got a message from a local OkCupid girl who I was flirting with, telling me that she was up there, and that the weather was supposed to be good for the weekend. I looked at the forecast again. She was right. Highs in the 70s and clear. I rented an SUV, packed my bike and gear in the back, and got moving around noon.

I got to the park at 4:30, sparing me about an hour to get food and a backcountry permit, and gear up for what I had spent months working up to: An overnight ride on the park road under the midnight sun.

The ranger at the backcountry office gave me a bear canister to bring along. It was huge, heavy, awkward, and almost didn’t fit into my cargo. But durable enough that not even a grizzly bear can bust it open and eat my food. I worked out a schedule with the ranger and was on my way. One day of riding overnight to Wonder Lake, 85 miles to the west, camp for the morning, camp again halfway back the next night, and then finish the day after that at the welcome center. If luck would have it, the mountain would show itself.

I got moving on the paved section of the park road between the headquarters and Savage River, which goes straight along the valley south of Mount Healy, a large 15 mile ridge system of rugged alpine ridges that tower above the taiga forests along the valley. At its summit of 5700 feet, it gives a good view of the Denali massif 60 miles southwest. I pushed onward through the valley under a light shower coming off of the mountains to the south. At this elevation, the forests started to thin out and I could see all of the mountains pretty clearly.

A short descent to the Savage River brought me to where the pavement ends and the fun begins. I stopped at the campground to refill my water and made small talk with a lady staying there with her family. She wanted to know where I was headed. They always do. People see me with the bike and all of my gear, covered in days worth of sweat and dirt, and always want to know where I’m headed. I don’t usually mind. Most of the time I’m ready to see people again after going alone for hours on end.

I crossed the river and started my climb around the side of Primrose Ridge, a small 1500 foot mountain mostly covered in tundra, and a popular spot in the park for day hikes. A short descent down the other side brought me to Sanctuary River and the mountains after it. I made it to the Teklanika River Campground thirty minutes later and took a break. I was making decent time. It was late evening, the elevation was well under the tree line, and the arctic mosquitoes were out in swarms.

From the below the bridge, the Tek River braided its way northward, narrowing through a large canyon and flowing out of the park. The midnight sun lit up the canyon and the mountains around, casting an alpenglow on the landscape. At that latitude it sets for a few hours into the night before coming up again around 3:45 a.m., but never far enough below the horizon that it doesn’t light up the northern sky in orange and gold. People say that the wilderness up there is pristine. When you see the midnight sun casting fire on hundreds of ridgelines, you know they aren’t kidding. I turned south and began my ascent up Igloo Canyon and Sable Pass.

In no time, I left the river, the mosquitoes and the tree line for what turned out to be the hardest uphill climb on the whole road. Ten miles of steep grades and thinning air, along with the fact that it was a dirt road, and that I had heavy cargo, thanks to that fucking bear canister, wiped me out not even halfway up. I was not expecting it to be that rough. But it was outright brutal.

The road went up Igloo Canyon for five miles, the tundra gave way to dirt, and soon I was spitting distance from the tops of ridges on both sides. It turned west for another 5 miles of hard uphill grades along Sable Pass. Ridges passed behind and below, more of them appeared a few miles south, and still, the road turned uphill again and again along the side of Sable Mountain. I stopped to take breaks I don’t know how many times. It made no difference. My training did nothing to prepare me for this. I guess I just had to take my time, something I couldn’t stand to do. I wanted to see the Mount McKinley from a bicycle, and I didn’t care what kind of beating I would end up taking to make it happen.

I pushed on and on between the rocky ridge tops and finally crested the pass just shy of 4000 feet before making an 850 foot descent to the East Toklat River, and then another climb back to the nearly the same elevation along the side of Polychrome Mountain. I was wearing out, standing on my pedals, pushing uphill with a shit load of cargo and thighs burning my legs alive. THIS HAS GOT TO FUCKING STOP. I came around a turn and a big grizzly bear stood right in the middle of the road twenty yards ahead.

SHIT!!!! I slammed on my brakes, sliding on the dirt and gravel. The bear jumped and took off down the hill, disappearing into a thicket of willow bushes. I stood there quietly for a few minutes, listening for it to come back, my heart rate completely off the charts. I was finally sure it was gone, and slowly rode by saying “Hey big guy! I’m not gonna bother ya.. Just passing on by, big fella!” After a hundred feet, I picked up the pace and got the hell out of there.

I reached the top of Polychrome Pass a few miles later. I had been climbing for two hours. Maybe more. I don’t know. But I had to stop and recover my strength. I didn’t have a choice anymore. With no one else out, I had the road to myself, and sat on the edge of a 1000 foot drop off, looking out at the valley ahead. The valley along Polychrome Mountain spans for five miles before sloping upward towards Mount Pendleton and the backbone of the Alaska Range. From there, five glaciers feed its streams, eventually joining the East Toklat further back. It is a diverse and colorful valley, and a popular overlook in the park. I rested for 45 minutes, taking in the solitude and trying to get my head together for the rest of the ride. On the bright side, I was high above the tree line with no worry of the mosquitoes, who I still hate to this day.

I coasted to the rest stop at Toklat River. It was 3 in the morning and I was finished. The rest up on the mountain didn’t do much for me. I undershot the difficulty on this trip, and just wanted to get back to the welcome center. I felt like a failure, but I had had enough. The next mountain pass had a climb of 950 feet, more of the same shit. And from where I was, I was just over half way to my goal. Whatever, I’ll see Denali some other time, maybe come out on a shuttle later the next day after getting some food and sleep. I decided to cut my losses, wait a few hours for a shuttle bus, and go back.

I didn’t even feel like finding a place to set up camp. My morale was altogether gone at this point. So I went into one of the outhouses, locked the door, got my pillow out, and went to sleep.

“Good Morning!” It was 6:00 a.m. A park ranger caught me sleeping in the outhouse. He was laughing.

“Hey uh, sorry, I’ll get out of here in a minute..” I sat up, half awake.

“No, don’t worry about it, get your rest! It’s a good shelter, isn’t it? I’ll go ahead and work on these other ones. Take your time and come out when you’re ready!”

Well that’s cool of him, I thought. I still felt a bit too weird staying there any longer, so I got up and came out.

We made small talk for a bit. He was an older fellow in his sixties, a bit eccentric, and happy to meet visitors. I told him about my trip, how I climbed all of those mountain passes, and was ready to just screw it and go back. He laughed.

“You sure you don’t want to go for it? The mountain is in the clear this morning!”

“No, I think I’ve had as much as I can take of this..”

He laughed again. “Well, you got all the way up Sable Pass, that’s pretty good!” I guess so. But I still felt like I had lost the battle.

I told him about the 500 pound beast that I scared off with my bike last night. “That’s a good bear,” the ranger reflected. “Well, I have to get some work done. The bus is coming in two hours. Just relax and walk around, go up on the ridge over there if you want. The sun should be coming up any minute.”

He went to work on the outhouses and I walked 100 feet up the facing ridge of the river and sat down. The sun had already lit up the Divide Mountain to the south. I relaxed and listened to the Toklat River rushing along, thought about everything I went through to get out there, and then I got my head out of the fog.

What the hell was I doing? I didn’t come all the way out here just to give up and turn around like a pussy. I spent months of planning, buildup, expensive decisions, just to get out to the park with my bike. And then the ride itself was even more trouble. And for what? To turn around and go back, one mountain pass away from my goal. And on a clear day, no less? I would never forgive myself for that. That’s not going to fucking happen. Not now. Not ever.

Fuck it, I’m going.

I came back down the ridge and got my gear together. The ranger saw me and came back over. “Change your mind?”

“Yeah, I’m going for it. I won’t forgive myself if I don’t. How far is it to Eielson?”

“About 13 miles. But you’ll see a better view before that at Stony Hill.”

“That’s doable. I think I can manage it if it’s just one more climb.”

“Yeah, you got a few hours rest, so that should help. Good luck!”

I said thanks, and got started on my climb towards Highway Pass, the highest point on the park road.

The road quickly ascended away from the tree line and into a narrow valley of tundra, and there was nothing easy about it. But I got my morale back, and with some rest, the last bit of strength I needed to climb through the barren, alpine country returned. Trees gave way to grass, grass gave way to dirt, and dirt gave way to rock. I pushed upward for 45 minutes, shedding layers and stopping at different times for water and energy bars. Up ahead, the snow capped ridge of Denali’s north summit appeared slowly at the top of the pass. THERE IT IS!!!! BY THE GODS!!!

More excited and delirious than ever, I crested Highway Pass, crossed a small stream and climbed a few hundred feet to Stony Hill Overlook, the first spot on the road where you can see the whole mountain. There it was, the face of Mount McKinley, the tallest mountain in North America, standing higher than anything I have ever seen. I had no idea that anything could be that huge and that magnificent.

WHAT!!! THE!!! FUCK!!!!!!!! I was out of my mind with exhaustion, hunger, caffeine deprivation, maybe some mild altitude illness. None of that mattered. As soon as I saw it, I knew it was worth every second of pain and suffering I had endured to get out there, at the end of the hardest and most backbreaking bike ride of my life. Whatever. I was there. The rest of the park was still waking up, but I was there, high up on Stony Hill, looking at a vista that would stay with me for the rest of my life, certain that nowhere else in our continent can any range of mountains rival that of Denali and her sisters in sheer size and majesty.

I finally calmed down and kept going. I had four miles left. I descended Stony Hill and went over Thorofare Pass, the last climb of the trip, and easily a short one. Down the gorge to my left, a family of caribou ran along the glacial headwaters of the Thorofare River, a tributary of the larger and more powerful McKinley, which flows westward across the valley ahead for 15 miles before turning northwest into the forested plains and beyond.

At mile 66, the Eielson Visitor Center sits on the side of one of Denali’s facing mountains, offering a great view of the range and a rest stop for tourists, water, restrooms, and a few exhibits. When I got there, arctic squirrels were frolicking around the picnic tables. The first eastbound shuttle wasn’t due for 45 minutes. So I sat down and waited.

Meanwhile, the first westbound bus showed up. Tourists got out and started taking pictures. Then another one stopped with even more people. Before long, the whole place was buzzing with tourists. An older couple saw me with my bike and gear, covered in dirt and a night’s worth of sweat and wanted to know where I was headed. I told them that I spent the night riding out there on the park road, was about to take a shuttle bus back to the park headquarters, get some food, and then drive back to Anchorage. They thought I was crazy, and they were right.

The shuttle bus showed up, I secured my bike in the back, sat down, and fell asleep before my head hit the seat.

The bus reached the welcome center a few hours later, I locked my bike in the rental SUV, got an unbelievably great tasting burger from the park restaurant, got rid of that fucking bear canister, and drove out of the park.

Even when the weather is outright awful, you can still find beauty and magic in Alaska. It’s everywhere. But when the sun comes out and lights up the land, there is really nothing like it. On that day, the mountains glowed an emerald green color in the midday sunlight. White clouds passed above the ranges, casting shadows on the ridges and valleys. I stopped everywhere on my drive back to take pictures.

When I stopped at the South Viewpoint to see Denali, it was already shrouded in clouds again, reminding me that like the rest of Alaska, it’s a beautiful place on its own terms.

I got back to my hotel a few hours later, took a long nap, and walked into downtown Anchorage for some well-earned seafood and craft beer.